ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

MUSIC, SONG, DANCE AND CLOTHES

– In a Swedish Aristocratic Family: 1740s to 1810s

Music in various forms was an integrated part of daily life and festivities, among other entertainment within the Piper family during the 18th century and into the next century. However, a detailed handwritten inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House includes no musical instruments. Still, it should not be read as an absence of music in this manor house in southernmost Sweden. Many popular musical instruments at the time – violins, flutes and various plucked string instruments – were all portable and regarded as personal belongings rather than inventories of a manor house. Music and dance were also regarded as one of the more pleasant leisure activities in Swedish aristocratic circles. This essay has been researched from a large selection of primary sources; inventories, correspondence, musical notes, songbooks and artworks – including some observations on fashionable garments at the time.

A well-preserved example of musical entertainment kept in the Piper Family Archive is this printed leaflet from the turn of the century 1800 (25 March), which gave information in German, French and English. The musicians presented themselves as ‘The Musical Family’ in a printed Theatre Nachricht (Theatre News) illustrated with the dark silhouette paper-cut portrait images of the mother, father, four daughters, four sons, their string instruments and notes. Additionally, the individual portraits give a glimpse into the consistency of the chosen male and female styles of upper garments and coiffures during the family’s performances. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX:17). Photo: The IK Foundation.

A well-preserved example of musical entertainment kept in the Piper Family Archive is this printed leaflet from the turn of the century 1800 (25 March), which gave information in German, French and English. The musicians presented themselves as ‘The Musical Family’ in a printed Theatre Nachricht (Theatre News) illustrated with the dark silhouette paper-cut portrait images of the mother, father, four daughters, four sons, their string instruments and notes. Additionally, the individual portraits give a glimpse into the consistency of the chosen male and female styles of upper garments and coiffures during the family’s performances. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX:17). Photo: The IK Foundation.Access to an instrument was undoubtedly connected to the family’s ownership in a manor house household and their visitors who may have brought their musical instruments to accompany their own song or others’ musical talents among guests or the host and hostess. Singing was also present in these homes, judging by a selection of handwritten songbooks kept in the historical Piper Family Archive. Such song leaflets have been preserved among Carl Fredrik Piper’s (1700-1770) and his son Carl Gustaf’s (1737-1803) documents. The late music historian Greger Andersson also emphasised that these 18th century texts, written by hand, represent a typical mix of themes for the period, including drinking songs, lyrical observations of Nature and ballads of a more philosophic or moral character. In total, about 200 pages were preserved, mainly written in the 1740s and 1750s, by several individuals, evidenced by the variation in handwriting styles.

Among this material, there is also to be found a substantial amount of ballads written for special occasions, like a complimentary poem to the ‘Countess E.C.B.’ on her birthday in 1742. Unfortunately, most such texts within this family circle lack information about the melody of each particular song. That is to say, notes were not written down. Even if some of the texts are added with a hint like ‘sings like this or that melody’, which to the greatest extent are unknown today. Such songs are assumed to have been popular and well known during a limited period, not seldom with their origin in French opera or vaudeville entertainment.

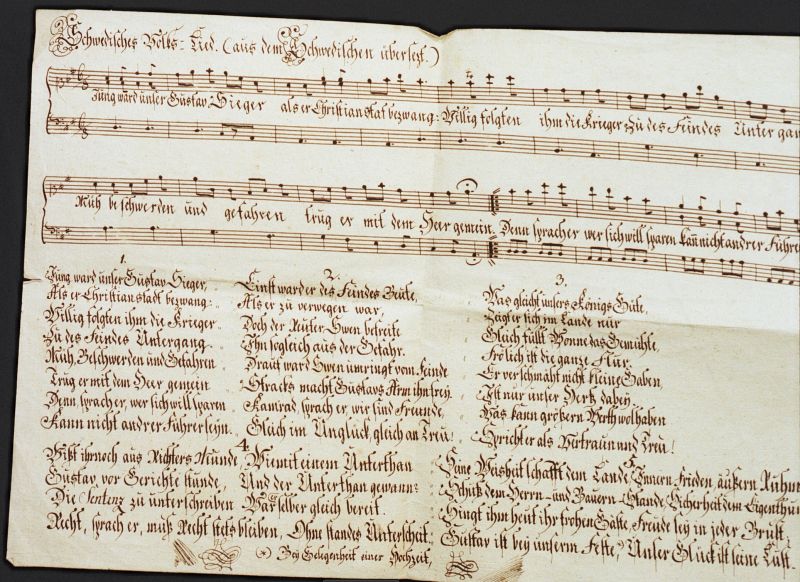

A few undated 18th century documents kept in the Piper Family Archive include notes as well as text. This unique example was written and drawn by hand with the German title ‘Schwedisches Folks Lied’ (Swedish Folk Song). (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX:18). Photo: The IK Foundation.

A few undated 18th century documents kept in the Piper Family Archive include notes as well as text. This unique example was written and drawn by hand with the German title ‘Schwedisches Folks Lied’ (Swedish Folk Song). (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX:18). Photo: The IK Foundation.Festivities were also frequent occurrences in the manor houses in southernmost Sweden – where music was an important part, particularly for dancing. Besides musical family members or guests, there is some uncertainty about who the hired musicians were on such occasions. They probably seem to have been town or city musicians travelling 30 to 60 kilometres from Kristianstad, Malmö or Ystad to entertain and stay overnight in one of the Piper family manor houses. Local fiddlers and other musicians were other possibilities, who could be requested for music and dance on shorter notice and at some manor houses of the nobility in Skåne; such fiddlers even had the sole privilege to play at weddings, christenings and other festivities within the geographical boundaries of the estate (Andersson, 1990).

‘Gustavian Style Interior with a Musical Party’ dating 1779. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. No: NM 2404).

‘Gustavian Style Interior with a Musical Party’ dating 1779. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. No: NM 2404).It is also essential to focus attention on the fact that several of the ballads and letters preserved in the Piper Family Archive indicate that Carl Gustav Piper had close connections to leading cultural persons within the court of King Gustav III (1746-1792) in particular, the composer and musician Carl Michael Bellman (1740-1795). Based on many such documents, it is highly likely that Piper belonged to the elite group of the Swedish aristocracy who, during his periods in Stockholm, took part in these entertainments at the court. This oil on canvas above, dating 1779, illustrates such court entertainment in the most detailed way. Violins, flutes, cellos and the grand piano with gold inlaying are in focus. Simultaneously, the luxuriously dressed individuals demonstrate the fashions of the time, which included the ‘National Costume’ of the nobility, introduced by Gustav III in 1778, just the year prior to this painting by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816). The lady and gentleman to the right wore such newly designed garments, a style that had been discussed and finally decided via a prize design competition where advantages, disadvantages etc., were considered. One reason for such an idea was the unreasonable desire for superfluity and extreme luxury, primarily learned from the French-styled fashions. The Swedish king, therefore, aimed for a unique Swedish fashion style. However, there were many critics of the reform. Even if still being a most exquisite choice of materials, plain silks were preferred, with silk ribbons and flounce decorations. The typical Renaissance-inspired lattice-worked sleeves on the female dress can be studied in several paintings from this period, whilst one of the male style designs consisted of all garments matching in black and red silk-velvet qualities – the shoes, stockings and wide cape were kept in the same colours too as seen in this painting. Interestingly, even if several historians during the last three decades have written in-depth articles, books and dissertations on the ‘National Costume’, this branch of fashion history was already researched by the late historian Eva Bergman during the 1930s and published in her book ‘Nationella dräkten – Gustaf III:s dräktreform 1778’ over 350 pages in 1938. Furthermore, in the years preceding the reform – 1773 to 1778 – several short theses, notices, articles and reflections were printed on the subject of this dress reform.

This drawing of a violin lesson circa 1770 in a wealthy Swedish home gives enlightening details of musical practice. The tutor watchfully guarded the two young boys when practising their violins. Music notebooks were placed on wooden stands, whilst further sheets of notes seemed to be placed on the table – which was moveable due to the small wheels on all six legs to be put aside when not in use – and a violin box on the floor. The clock pointed at almost five, demonstrating that this lesson occurred late afternoon. All individuals’ clothing and hairstyles were depicted in ordinary, everyday upper-class fashion. Consisting of a collarless short coat, waistcoat and breeches, probably of matching fabric, a ruffled shirt, silk or woollen stockings, low-heeled buckled shoes, and a wig was drawn back and tied with a silk ribbon. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Drawing, probably made by Jean E. Rehn).

This drawing of a violin lesson circa 1770 in a wealthy Swedish home gives enlightening details of musical practice. The tutor watchfully guarded the two young boys when practising their violins. Music notebooks were placed on wooden stands, whilst further sheets of notes seemed to be placed on the table – which was moveable due to the small wheels on all six legs to be put aside when not in use – and a violin box on the floor. The clock pointed at almost five, demonstrating that this lesson occurred late afternoon. All individuals’ clothing and hairstyles were depicted in ordinary, everyday upper-class fashion. Consisting of a collarless short coat, waistcoat and breeches, probably of matching fabric, a ruffled shirt, silk or woollen stockings, low-heeled buckled shoes, and a wig was drawn back and tied with a silk ribbon. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Drawing, probably made by Jean E. Rehn).Other contemporary Swedish musical arrangements with links to the Piper family, as well as the image above, may be compared via documents related to the wealthy count and politician Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770) and his family at the Åkerö manor house (c.1757-70), for instance, that the young ladies sometimes played on their harpsichord. According to in-depth research of this manor house by the late historian Gösta Selling, this particular instrument was of a smaller transportable model. On another occasion, when the Tessin family had guests staying over, it was recorded that the young people danced the contredanse, and the others admired the entertainment. Furthermore, later documents from the archive kept at the Christinehof manor house also give evidence for music linked to young aristocrats via Carl Gustaf Piper’s three sons attending a military school in Colmar during the 1780s. Carl Claes, Gustaf and Eric played violin and harpsichord as part of their weekly timetable and learned to dance.

In conclusion, this illustrative watercolour of musical entertainment, handicrafts and everyday life in a drawing room at Löfstad manor house in 1812 is packed with informative details of a wealthy Swedish home at the time. Fashionable matching white and blue linen wall covering and upholstering set the scene, together with porcelain of East Indian origin, candelabras, a cut-glass chandelier, artworks, and leather-bound volumes placed on a table, and a style of curtain arrangements in vogue, three family dogs and much more. At the same time, the depicted individuals were part of or linked to the Piper family. The lady, Sophie Piper (1857-1816), was visibly active with her ongoing knitting dressed in a high-waistline dress or the so-called empire silhouette. Her son Carl Fredrik Piper (1785-1859), playing his guitar, was probably wearing the up-to-date fashion of a double-breasted frock coat in black over a red-coloured waistcoat and grey trousers (not in the picture). Whilst his 25-year-old senior card-playing French visitor, Duke of Piennes, seems to be dressed in a coat in the shape of a cutaway in front with long tails behind and a standing collar, breeches and black leather boots – a style often seen already in the late 18th century. He was also the painter of this watercolour interior – and his actual name was Louis Marie Celeste d’Aumont (1762-1831). (Courtesy: Östergötland Museum, Sweden. OM.OML.001720. Public Domain. DigitaltMuseum).

In conclusion, this illustrative watercolour of musical entertainment, handicrafts and everyday life in a drawing room at Löfstad manor house in 1812 is packed with informative details of a wealthy Swedish home at the time. Fashionable matching white and blue linen wall covering and upholstering set the scene, together with porcelain of East Indian origin, candelabras, a cut-glass chandelier, artworks, and leather-bound volumes placed on a table, and a style of curtain arrangements in vogue, three family dogs and much more. At the same time, the depicted individuals were part of or linked to the Piper family. The lady, Sophie Piper (1857-1816), was visibly active with her ongoing knitting dressed in a high-waistline dress or the so-called empire silhouette. Her son Carl Fredrik Piper (1785-1859), playing his guitar, was probably wearing the up-to-date fashion of a double-breasted frock coat in black over a red-coloured waistcoat and grey trousers (not in the picture). Whilst his 25-year-old senior card-playing French visitor, Duke of Piennes, seems to be dressed in a coat in the shape of a cutaway in front with long tails behind and a standing collar, breeches and black leather boots – a style often seen already in the late 18th century. He was also the painter of this watercolour interior – and his actual name was Louis Marie Celeste d’Aumont (1762-1831). (Courtesy: Östergötland Museum, Sweden. OM.OML.001720. Public Domain. DigitaltMuseum).Sources:

- Alm, Mikael, Sartorial Practices and Social Order in Eighteenth-Century Sweden: Fashioning Difference, Routledge, New York 2021.

- Andersson, Greger, ‘Häradsspelmän i Albo härad’, Skepparpsåns museiförening. Meddelanden & Bygdehistorik, 1990:4, pp. 244-253.

- Andersson, Greger, ‘Musiken i hemmet under 1700-talet’, Kulturen 1991, pp. 182-193.

- Bergman, Eva, Nationella dräkten – Gustaf III:s dräktreform 1778, Stockholm 1938.

- Christinehof Manor house, Sweden (research visits in the 1990s and 2016).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘På Bellmans tid – Nöjesliv och underhållning under 1700-talets andra hälft i adelskretsar på Österlen’, Österlen 1998, pp. 61-68.

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, (Piper Family Archive, no D/I: Inventory Krageholm. D/IX: documents related to music and song. E/III. Military school in Colmar).

- LIBRIS, National Library of Sweden. Search words: ‘Nationella dräkten’ [National Costume].

- Selling, Gösta, Svenska Herrgårdshem under 1700-talet, Stockholm 1937 (pp. 127-128).

- Östergötland Museum, Sweden. DigitaltMuseum. (Identification of the depicted persons in the painting, dated 1812. OM.OML.001720).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE