ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

NATURAL & EARLY SYNTHETIC DYES

– A Textile Study in Philadelphia

This fifth observation from North America was inspired by a visit last summer to the most interesting Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. The aim of this essay is to give some comparable views of dyeing methods, from before as well as after the introduction of synthetic dyes, by discussing and illustrating a few gems from its museum and research library. Textile dyeing is overall a complex process, but the craft also has a number of separate functions/limitations – as a sign of wealth and status, long-living local traditions, amateur or specialist dyers perspectives, water and light resistance considerations or just the desire for a beautiful colour.

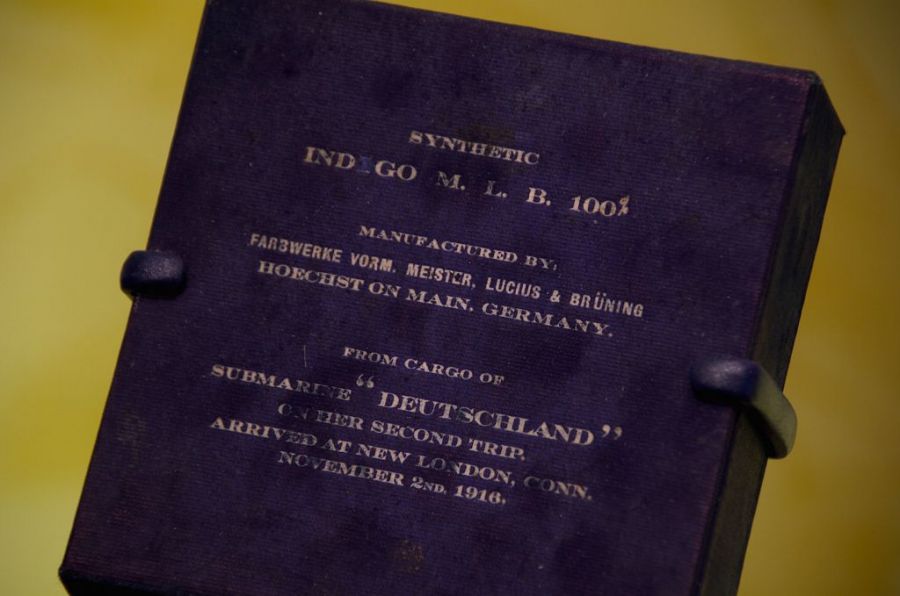

Box of synthetic indigo dye, ca. 1916. (From the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014).

Box of synthetic indigo dye, ca. 1916. (From the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014).The basic chemical structure of synthetic indigo was worked out by the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer in 1865, but difficulties arose when synthesising the “new indigo”, and therefore, the substance was first fully developed around 1880. During the coming decades, it became a widespread dye substance, gradually making the lucrative indigo plantations in numerous countries unprofitable. The synthesised form of the popular blue dye became cheaper as well as quicker to produce, and Jenny Balfour-Paul describes in her book Indigo (pp 81-87) that a smaller number of chemical producers in the 1890s – initially German, Swiss and French – dominated the market.

Additionally, the illustrated box of synthetic indigo dye and its informative printed text enlighten the history of demand, transportation and the awakening production of this dye in the U.S. for jeans and other garments/fabrics. The exhibition states in this matter: ‘To satisfy customers’ perennial preference for the color blue. American dyers eagerly bought the synthetic indigo carried by the submarine Deutschland. But they soon discovered that dissolving the highly compressed German dye cakes was nearly impossible, forcing them to buy from the U.S. companies just starting indigo manufacture.’

Some further search into the history of this submarine reveals that Deutschland was built in 1916 as a blockade-breaking German merchant submarine and acted as one of seven freighters of this type carrying cargo to the U.S. during the First World War. This particular submarine made two journeys only as a cargo submarine (1916), whereof the piece of indigo illustrated here was carried on the second. However, it was primarily on the first journey as dyestuff was carried in substantial quantities (125 tons), probably due to the problems cited above with highly compressed indigo.

The Museum exhibition also describes that the Navajo have had a long tradition of using natural dyes, but with the introduction of synthetic substances a gradual change gave way to greater variations and the possibility to buy synthetically dyed yarn. Noted as follows; ‘The brightly colored rugs and other textiles woven by the Navajo during the 1860s and 1870s became known as “Germantowns,” after Germantown, Pennsylvania, home to the mills that produced the synthetically dyed yarn. This lightweight, brilliantly colored yarn in shades of red, blue, green, purple, black, and yellow never before available to the Navajos enabled weavers to create new, intricate designs of dazzling complexity.’ (Exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014).

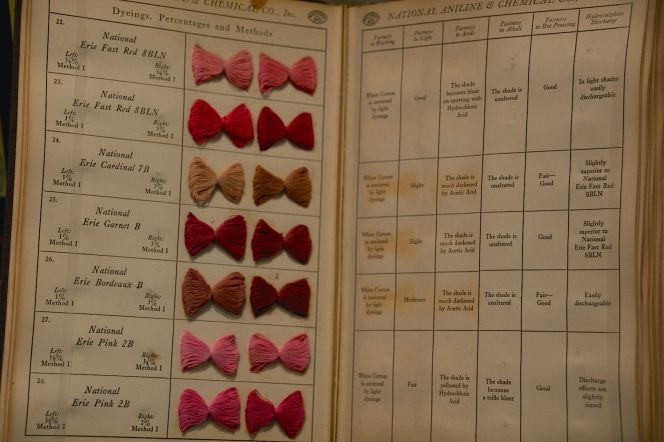

The Museum exhibition also describes that the Navajo have had a long tradition of using natural dyes, but with the introduction of synthetic substances a gradual change gave way to greater variations and the possibility to buy synthetically dyed yarn. Noted as follows; ‘The brightly colored rugs and other textiles woven by the Navajo during the 1860s and 1870s became known as “Germantowns,” after Germantown, Pennsylvania, home to the mills that produced the synthetically dyed yarn. This lightweight, brilliantly colored yarn in shades of red, blue, green, purple, black, and yellow never before available to the Navajos enabled weavers to create new, intricate designs of dazzling complexity.’ (Exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014). The science of colour illustrated by a late 19th century Sample book of aniline/chemical dyes. (From the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014).

The science of colour illustrated by a late 19th century Sample book of aniline/chemical dyes. (From the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”). Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014). Going back in time to pre-synthetic dyes – here pictured with a professional dyer hanging ramie cloth to dry in the 1820s China. Watercolour on pith paper (Reproduction) in the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”. One of sixty-two water colour images. Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014).

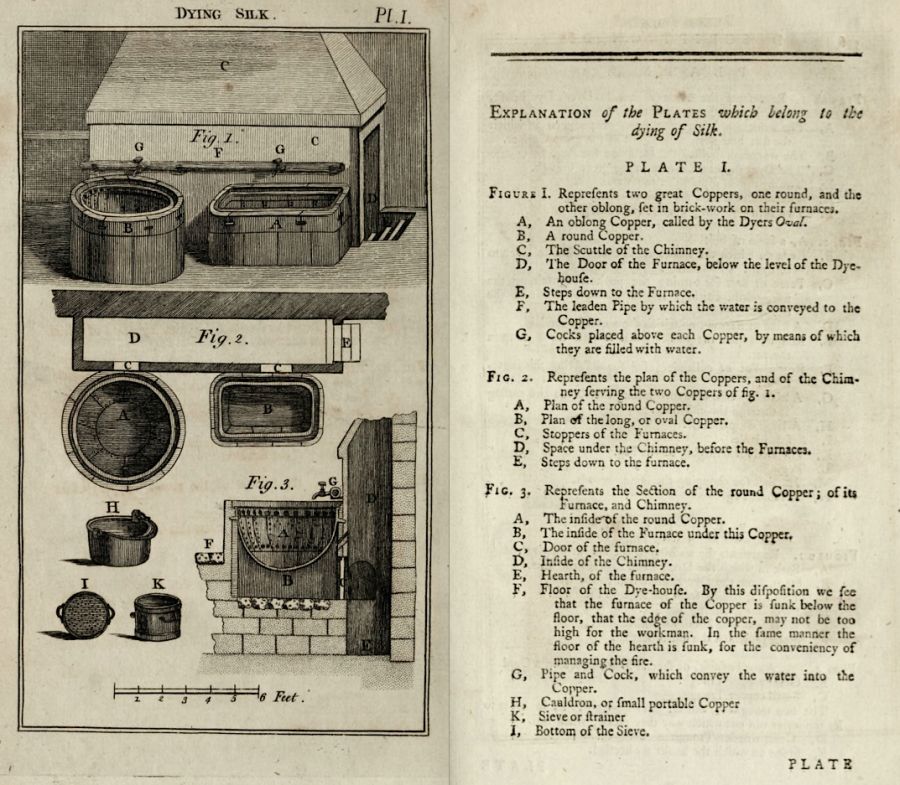

Going back in time to pre-synthetic dyes – here pictured with a professional dyer hanging ramie cloth to dry in the 1820s China. Watercolour on pith paper (Reproduction) in the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity”. One of sixty-two water colour images. Photo: The IK Foundation, London (2014). For a brief study of natural dyes, I visited the Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library (Rare Books) at the same Foundation. This library holds a selection of pre-1800 dye books, predominately European. One such example is The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton by Jean Hellot – printed in London in 1789. The book is translated from French, and each part of the book is translated by a different translator, which is not an entirely unusual way for an 18th-century dye book. Translations from or to German, French, Swedish, English, etc, are something experienced several times when studying early dye books in both Sweden and England. Meaning that many recipes are repeated over and over again with some variations, additionally, the “borrowing” of images from one book to another was not uncommon!

This book, printed in 1789, comprises more than 500 pages, including very detailed descriptions/recipes, divided into three sections clearly separated due to the various methods for wool, silk and cotton & linen thread. Several descriptions assist each dye plant, insect body or mollusc shell based on knowledge of its roots in the 17th century or even earlier. These dyeing instructions were primarily intended for professional dyers, while most recipes are complex in various degrees and can not be carried out without one or several imported dyestuffs.

Plate I from Jean Hellot’s dye book ‘The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton’, printed in London 1789.

Plate I from Jean Hellot’s dye book ‘The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton’, printed in London 1789.A selection of recipes follows to demonstrate some of the significant variations – especially for red, blue and green colours – included in the 1789 publication.

- Dyeing Wool: The cold Indigo Vat with Urine, Gum-lac Scarlet, Madder Red, The colours obtained from a mixture of Blue and Red, The method of blending Wool of different colours, for mixed Cloths or Stuffs, Brasil Wood, French Berries etc.

- The Art of Dyeing Silk: For boiling of silks intended to be Dyed, Remarks on Crimson, False Rose colour, Softening of Black, Violet Crimson of Italy, Genoa Black for Velvets etc.

- The Art of Dying Cotton and Linen Thread…: Theory of dying stuffs prepared with alum, Cochineal and colouring insects, Red Cinnamon, Olive and Duck Greens, Saxon Blue etc.

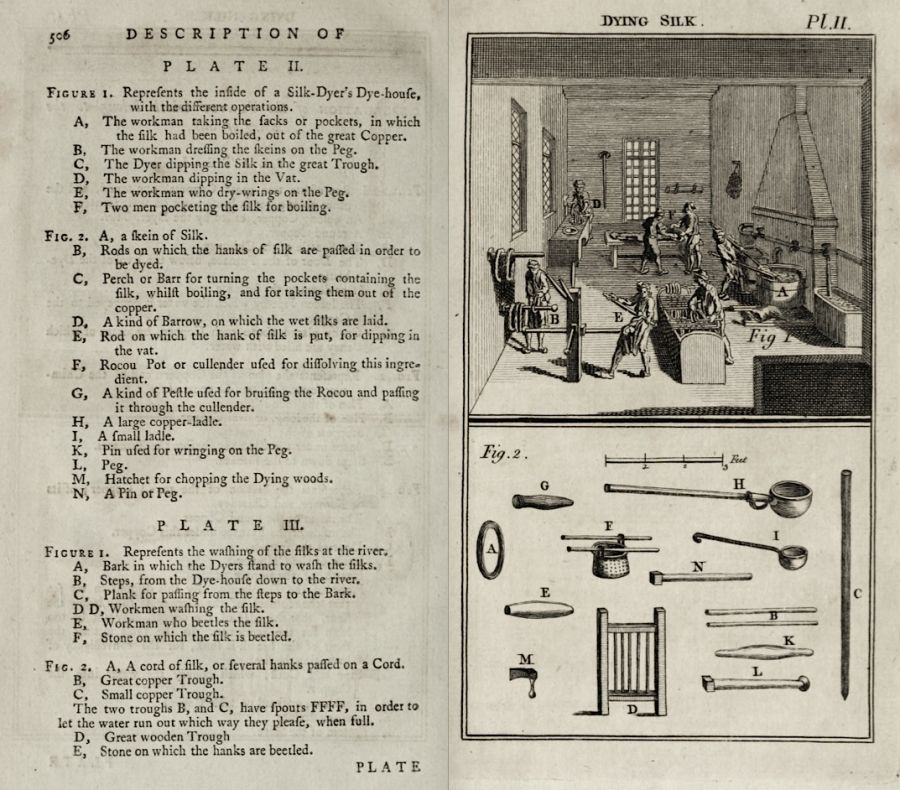

Plate II from Jean Hellot’s dye book ‘The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton’, printed in London 1789.

Plate II from Jean Hellot’s dye book ‘The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton’, printed in London 1789.It is always a privilege and joy to handle a rare 18th century publication. Still, this informative book can also be found in full text online.

Sources:

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny, Indigo, London 1998.

- Chemical Heritage Foundation [since February 2018, Science History Institute ], Philadelphia, US. (Summer 2014, Bridge Builder Expeditions – North America: Visit at the Museum exhibition “Making Modernity” & Visit at Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library: Rare Books).

- Hellot, Jean, The Art of Dying Wool, Silk and Cotton, London 1789.

- Wikipedia (Search words: 'German submarine Deutschland' ).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE