ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

NATURAL HISTORY AND CURIOSITIES

– A Case Study of Global Traditions, Textiles and Museums in the 18th century

Carded cotton, bark cloths, a pair of socks and New Zealand flax were some of the textile objects mentioned in connection to collections of natural history by Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen apostles in their travel journals and correspondence. Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) noted, for instance, from Japan in 1776: ‘On the 26th of May, before we left this place, we made a purchase of several elegant, but small, boxes of shells, which were laid up very neatly and curiously on carded cotton. These are generally bought by the Dutch, either to sell again, or to send to Europe to their friends and relations, as rarities from so distant a country. Although the shells were all fastened to the cotton with glue made of boiled rice, in order that they might not fall off, I picked out as many as were not before known in Europe, or at least very scarce, and which are now kept amongst other collections of the Academy at Uppsala.’ This essay will look closer at display methods and interior spaces used for such “curious” objects.

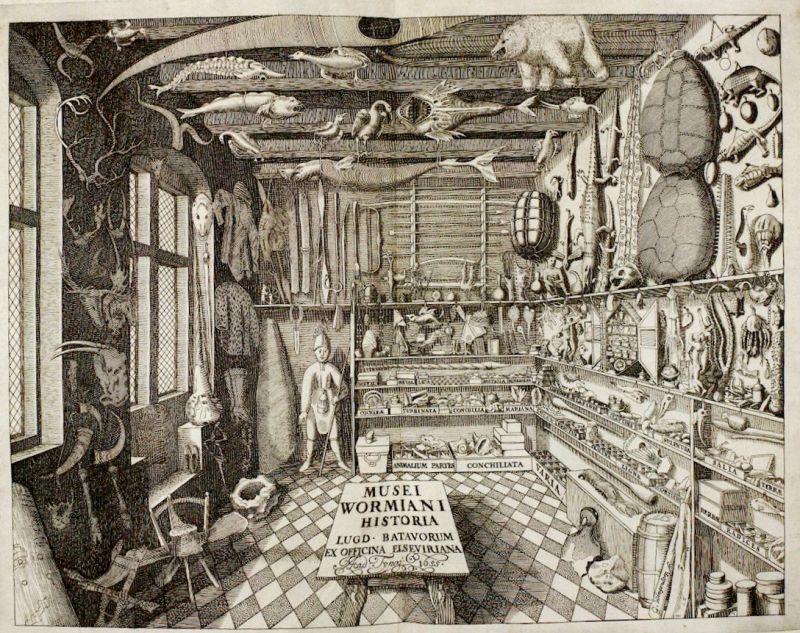

To arrange a cabinet of curiosities was a well-established tradition already in the 17th century, which this image demonstrates with its rich variety of “curious objects”, including garments seen as “exotic” among numerous ethnographical, natural history objects, etc. Such arrangement and classification replaced the original use of an object or natural habitat for a living organism.|Text in picture: ’Ole Worm (1588-1654), a doctor and professor of natural philosophy in Copenhagen, used his collection to teach students’. (Courtesy: Smithsonian Libraries, see sources).

To arrange a cabinet of curiosities was a well-established tradition already in the 17th century, which this image demonstrates with its rich variety of “curious objects”, including garments seen as “exotic” among numerous ethnographical, natural history objects, etc. Such arrangement and classification replaced the original use of an object or natural habitat for a living organism.|Text in picture: ’Ole Worm (1588-1654), a doctor and professor of natural philosophy in Copenhagen, used his collection to teach students’. (Courtesy: Smithsonian Libraries, see sources).One of the travelling apostles, the naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752), was deeply in debt at the time of his death in February 1752; due to that, his collections were kept in Smyrna [today Izmir] by his creditors. Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was extremely anxious to get the whole affair sorted out and arrange for the young apostle’s collected natural specimens and objects of curiosity to be transported to Sweden. Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden, who had already embarked on a collection of natural history specimens in the 1740s, was in the end persuaded to help. She had the financial resources to buy Hasselquist’s collection while also wishing to augment her already considerable natural history cabinet. She redeemed the collection in 1754 at a price of 14,000 Daler in copper coins [Rixdollar copper coin]; a collection comprising a considerable quantity of natural history objects, manuscripts, antiques and ethnographic objects from the areas he visited during his travels. Moreover, Linnaeus had his apostle’s diary published in 1757. Although the major part of Hasselquist’s avidly collected items from his sojourn in the eastern Mediterranean region ended up in his home country, there were evidently some still left in Smyrna with the consul Anders Rydelius, which the natural historian Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) mentioned in his diary writing almost a decade later: ‘I was also shown several curious remnants from Dr Hasselquist’s original collections which had not been brought to Sweden with the rest’. Whether those parts of the collection, which were seen in June of 1761, remain in Smyrna, have been lost or been brought to Sweden at a later date is not known. As far as is known, Hasselquist did not collect any textile ethnographic artefacts except for a mummy with its linen shroud from Egypt, originally kept in the Drottningholm Palace. Today, the mummy is to be found in the Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities’ collection in Stockholm, dating 945-656 BC. Hasselquist’s collections have over more than two centuries been dispersed, as have other collected natural history and ethnographic specimens collected by Lovisa Ulrika, and divided between their original milieus at Drottningholm Palace and various museum collections in Sweden.

Queen Lovisa Ulrika (1720-1782), portrayed in 1768 by Lorens Pasch the Younger (1733–1805). During the time of Fredrik Hasselquist’s death in 1752, she was still quite a young woman and in the process of creating her natural history collection. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden, NMGrh 1375. Wikimedia).

Queen Lovisa Ulrika (1720-1782), portrayed in 1768 by Lorens Pasch the Younger (1733–1805). During the time of Fredrik Hasselquist’s death in 1752, she was still quite a young woman and in the process of creating her natural history collection. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden, NMGrh 1375. Wikimedia).Peter Forsskål took part as a naturalist in The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia from January 1761 until his death in July 1763. During this time, he made some comparable notes in his journal from what he had studied at a cabinet in Sweden before his travels. Foremost, in the strategically situated port of Smyrna for exports as well as imports, where the European merchants had had important connections for over a hundred years by the time Forsskål arrived. There, he observed a kind of mussel called ‘Pinnae ’ (Pinna nobilis), which was to be eaten raw or fried in oil. It was, however, the “wool” or sea silk attached to the mussel, which was described as of a sea-green colour, fine as silk, and could easily be spun. Besides, it was noted: ‘There is a pair of socks worked from this flax in the Cabinet at Drottningholm in Sweden’. Maybe there were budding hopes that those plentiful mussels could in the future become a beneficial complement to other spinning materials for the production of clothes and interior textiles.

It was not only natural historians, captains and a wide spectrum of other travellers who collected/bartered/purchased/plundered objects, which were to be donated or sold to curious- or natural history cabinets in Europe. One such individual lived in Egypt and was mentioned by Peter Forsskål in Alexandria, October 1761: ‘The whole of this area is a mass of ruins constructed from every kind of building material, which will give the lover of antiquities plenty of food for thought… The rubble from all these ruins is worth searching through; even if it does not yield up treasures of financial value, it may well provide antique objects, precious to connoisseurs. The famous French Dragoman Roboli is widely known in Europe for accepting commissions to search out such things and dispatch them to those interested. This activity has added to his understanding of the subject.’ This depiction of the Inner Gallery of the Royal Museum at the Royal Palace in Stockholm shows one such example of a cabinet/early museum in the Linnaeus Apostles’ home country. Oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) of wealthy visitors dressed in the latest fashion in 1796, who admired antiquities from the Mediterranean area. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden, NM 964. Wikimedia).

It was not only natural historians, captains and a wide spectrum of other travellers who collected/bartered/purchased/plundered objects, which were to be donated or sold to curious- or natural history cabinets in Europe. One such individual lived in Egypt and was mentioned by Peter Forsskål in Alexandria, October 1761: ‘The whole of this area is a mass of ruins constructed from every kind of building material, which will give the lover of antiquities plenty of food for thought… The rubble from all these ruins is worth searching through; even if it does not yield up treasures of financial value, it may well provide antique objects, precious to connoisseurs. The famous French Dragoman Roboli is widely known in Europe for accepting commissions to search out such things and dispatch them to those interested. This activity has added to his understanding of the subject.’ This depiction of the Inner Gallery of the Royal Museum at the Royal Palace in Stockholm shows one such example of a cabinet/early museum in the Linnaeus Apostles’ home country. Oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) of wealthy visitors dressed in the latest fashion in 1796, who admired antiquities from the Mediterranean area. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden, NM 964. Wikimedia).![Another contemporary example is the beater for bark cloth at the bottom of the picture, shown here, along with other tools, used locally on Otaheiti [Tahiti] and nearby islands, depicted by the artist Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) during the period April-August 1769 – accompanied by the Linnaeus’ apostle and naturalist Daniel Solander (1733-1782) et al on James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage. This tool is one of many hundreds of ethnographic items brought back from Cook’s voyages, which after their return to Europe and England initially ended up in the collectors’ own hands, in other private ethnographic collections, museums of an early date or in scientific natural history cabinets in Europe. In the 19th century and further into the next century the objects were gradually sorted, sold, re-arranged or donated to museums and institutions in Europe as well as in other continents. Today ethnographic objects from those voyages can be seen and studied at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford and several other museums in England, Museum of Ethnography Stockholm, Sweden, Georg-August University of Göttingen in Germany, Museum of New Zealand, National Museum Australia etc. As well as equivalent objects used in local traditional craft at the Musée de Tahiti et des îles. (Image from: Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages…, 1773, vol. 2, plate 9).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4-hawkesworth-664x828.jpg) Another contemporary example is the beater for bark cloth at the bottom of the picture, shown here, along with other tools, used locally on Otaheiti [Tahiti] and nearby islands, depicted by the artist Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) during the period April-August 1769 – accompanied by the Linnaeus’ apostle and naturalist Daniel Solander (1733-1782) et al on James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage. This tool is one of many hundreds of ethnographic items brought back from Cook’s voyages, which after their return to Europe and England initially ended up in the collectors’ own hands, in other private ethnographic collections, museums of an early date or in scientific natural history cabinets in Europe. In the 19th century and further into the next century the objects were gradually sorted, sold, re-arranged or donated to museums and institutions in Europe as well as in other continents. Today ethnographic objects from those voyages can be seen and studied at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford and several other museums in England, Museum of Ethnography Stockholm, Sweden, Georg-August University of Göttingen in Germany, Museum of New Zealand, National Museum Australia etc. As well as equivalent objects used in local traditional craft at the Musée de Tahiti et des îles. (Image from: Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages…, 1773, vol. 2, plate 9).

Another contemporary example is the beater for bark cloth at the bottom of the picture, shown here, along with other tools, used locally on Otaheiti [Tahiti] and nearby islands, depicted by the artist Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) during the period April-August 1769 – accompanied by the Linnaeus’ apostle and naturalist Daniel Solander (1733-1782) et al on James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage. This tool is one of many hundreds of ethnographic items brought back from Cook’s voyages, which after their return to Europe and England initially ended up in the collectors’ own hands, in other private ethnographic collections, museums of an early date or in scientific natural history cabinets in Europe. In the 19th century and further into the next century the objects were gradually sorted, sold, re-arranged or donated to museums and institutions in Europe as well as in other continents. Today ethnographic objects from those voyages can be seen and studied at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford and several other museums in England, Museum of Ethnography Stockholm, Sweden, Georg-August University of Göttingen in Germany, Museum of New Zealand, National Museum Australia etc. As well as equivalent objects used in local traditional craft at the Musée de Tahiti et des îles. (Image from: Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages…, 1773, vol. 2, plate 9). A homely portrait of the botanist Jan Frederick Gronovius’ naturalist son Laurens Theodoor Gronovius (1730-1777) and his children. Gronovius “the Elder” (1690-1762), who passed away a fifteen year before this painting was made, was a patron of the young Carl Linnaeus during his time in Leiden and the two men kept up an extensive correspondence over the years from about 1735 to 1756. This depiction gives an interesting and rare insight into knowledge over generations, when his son and grandchildren were illustrated in 1775 with all possible objects worthy of a successful man of science. Highlighted by the cabinet with drawers, a reptile kept in a glass jar filled with spirits, botanical plates, a potted plant, corals, a globe, natural history books etc. Whilst of textile interest – the floor was covered with a large sized colourful Caucasian carpet. (Courtesy: Lakenhal Museum, Leiden. Painted by Isaac L. la Fargue van Nieuwland. Wikimedia Commons).

A homely portrait of the botanist Jan Frederick Gronovius’ naturalist son Laurens Theodoor Gronovius (1730-1777) and his children. Gronovius “the Elder” (1690-1762), who passed away a fifteen year before this painting was made, was a patron of the young Carl Linnaeus during his time in Leiden and the two men kept up an extensive correspondence over the years from about 1735 to 1756. This depiction gives an interesting and rare insight into knowledge over generations, when his son and grandchildren were illustrated in 1775 with all possible objects worthy of a successful man of science. Highlighted by the cabinet with drawers, a reptile kept in a glass jar filled with spirits, botanical plates, a potted plant, corals, a globe, natural history books etc. Whilst of textile interest – the floor was covered with a large sized colourful Caucasian carpet. (Courtesy: Lakenhal Museum, Leiden. Painted by Isaac L. la Fargue van Nieuwland. Wikimedia Commons).Privately owned museums were built on a long tradition of earlier cabinets of curiosity in Europe, displayed in various formats from one single cupboard to spacious collections stretching over a number of rooms. Many specimens were preferred to be exhibited in specially designed uniform wooden glass display cabinets to give the visitors or guests a close-looking view as well as protect the objects. At times, well-to-do individuals collected specimens themselves, or more often paid others to acquire the desired objects, made exchanges with similar-minded collectors in their network or made purchases at auctions. Influence by barter and local traditions became extensive in a “global collecting aim” for the travelling naturalists et al. Journals, correspondence, etc., provide evidence that local indigenous people often had a central active role in the frequent exchange of objects and knowledge. The general curiosity of almost everything during the period, together with the increasing aim to systematise Nature and the myriad of associates involved, also came to inspire some individuals to establish museums in 18th century Europe, which will be looked at more closely in a forthcoming publication.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Volume Four: Journals of Fredrik Hasselquist & Peter Forsskål).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 166, 195-96 & 210).

- Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages undertaken by the order of his present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere..., London 1773.

- Laine, Merit, En Minerva för vår Nord – Lovisa Ulrika som samlar, uppdragsgivare och byggherre, Uppsala 1998.

- Löwegren, Yngve, Naturaliekabinett i Sverige under 1700-talet, Lund 1952.

- Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities (Medelhavsmuseet), Stockholm, NME 010a: Egyptian mummy/Hasselquist.

- Smithsonian Libraries (digital image source & quoted information in translation): Ole Worm, Museum Wormianum; seu, Historia rerum rariorum, tam naturalium, quam artificialium, tam domesticarum, quam exoticarum…, Leiden 1655.

- The Linnaean Correspondence. (Letters preserved: from [Johann] Frederik Gronovius to Carl Linnaeus, c. 1735 to 1756).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE