ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

NATURALIST, PHYSICIAN AND TEXTILE MANUFACTURER

– Anders Sparrman’s Life in the 1770s to 1810s

Anders Sparrman – one of Carl Linnaeus’ long-distance travelling Apostles – mainly worked as a naturalist and physician. However, despite his interest in bark cloth, textile dyeing and local clothing in various parts of the world via James Cook’s second voyage during the 1770s, he was a rather unlikely individual around the turn of the year 1800 to be the owner of textile manufacturing. Even so, Sparrman had more than one such engagement. This essay will look closer into his linen and calico print-works, assisted by a selection of illustrations from the original Swedish handwritten documents. Some of these detailed lists are presented for the first time in English transcriptions. Together with brief reflections on his other lines of occupations, to give a deeper understanding of how global cultures in a textile context could be intertwined with local work in Stockholm.

A lively depiction of Stockholm around 1797, contemporary to when Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) became involved in the linen and cotton print-works in Järva, situated on the northern fringe of the capital. At the time when he also still worked at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with the cabinet of natural history specimens at Stora Nygatan (1777 to 1798) in the Old Town. It was just out of the picture if one followed a few streets to the right of the illustrated Royal Palace. |Coloured engraving by Johan Fredrik Martin (1755-1816). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. alvin-record:80986. Public Domain).

A lively depiction of Stockholm around 1797, contemporary to when Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) became involved in the linen and cotton print-works in Järva, situated on the northern fringe of the capital. At the time when he also still worked at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with the cabinet of natural history specimens at Stora Nygatan (1777 to 1798) in the Old Town. It was just out of the picture if one followed a few streets to the right of the illustrated Royal Palace. |Coloured engraving by Johan Fredrik Martin (1755-1816). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. alvin-record:80986. Public Domain).

The Järva Cotton Print-works in Stockholm was run by the manufacturer Stephen Bennet (1691-1757) and his family from 1797 until around 1810, with Anders Sparrman as one of the partners up to the year 1803. The production at the works was studied by the late textile historian Ingegerd Henschen in her analyses of fabric printing, the following can for example be found in her book on the subject: ‘The printing works was situated at the location Vargtorpet at Järva and generally referred to as Järva print-works or Järva linen and calico print-works. It was no cotton mill in the true sense of the word, although quite a lot of calicoes and tablecloths were printed on cotton there, but also quite a number of other fabrics…’. Links have also been found between Sparrman and the textile manufacturing mentioned above via documents at the Stockholm City archives. It is stressed in the book chapter (Broberg et al. ed., 2012) that ‘After some searching among the diaries at Stockholm magistrate’s court, it emerged that Anders Sparrman had been bankrupted in 1805. From the documents can be understood that in partnership with Captain Stephen Bennet, he had run cotton print-works and dye-works between the years 1797 and 1803…’

Documents to do with Sparrman’s financial interest in textile manufacturing are also still extant at the National Archive in Stockholm, several handwritten pages were rediscovered during my research for the monograph Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade. Primary sources are illustrated in the three images below, including various fabric qualities, chemicals, dyes, etc., connected to this manufacture. The Järva print-works were not his only involvement in the textile line, as he was also financially involved in a linen and cotton manufacture in the capital, which wove fabrics between 1796 and 1800. The late historian Sven T. Kjellberg explained that Sparrman’s manufacture produced ‘cotton, linen and stuff ’. [See sources; for the three quotes in translation].

Depiction of Anders Sparrman, which was used in this Swedish memorial stamp from 1973 – about two hundred years after he worked as an assistant botanist on James Cook’s (1728-1779) second voyage from 1772 to 1775. The portrait originates from an engraving by Hubert after a drawing by M. Mollard. Sparrman was portrayed at an unknown date, but probably in the early 1780s, that is to say, 15 to 20 years before his involvement in textile manufacturing. (Swedish stamp, 1 krona).

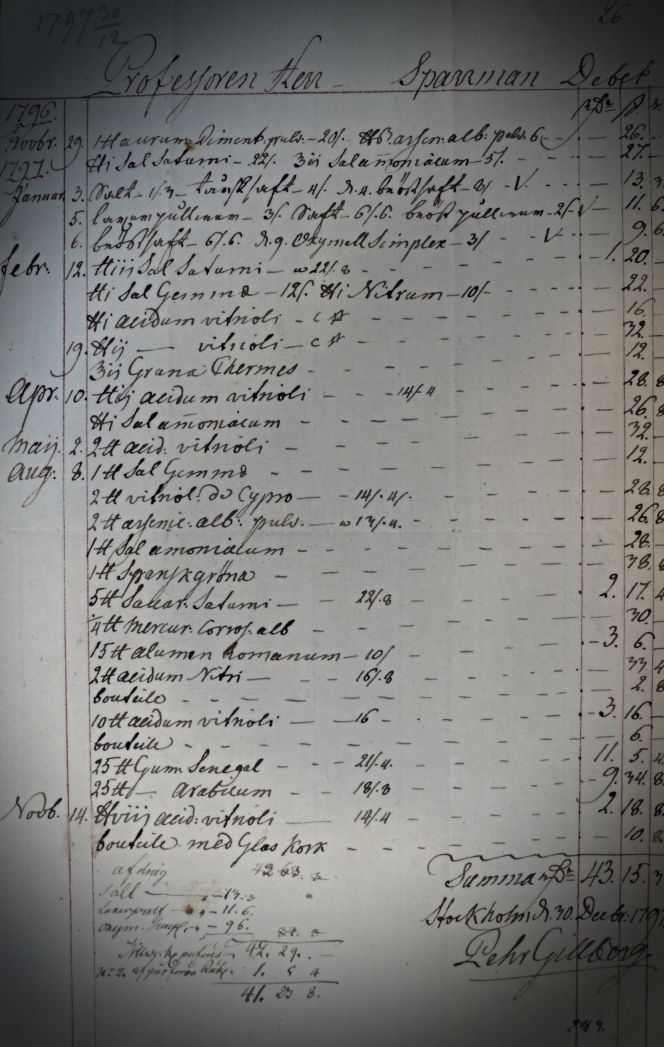

Depiction of Anders Sparrman, which was used in this Swedish memorial stamp from 1973 – about two hundred years after he worked as an assistant botanist on James Cook’s (1728-1779) second voyage from 1772 to 1775. The portrait originates from an engraving by Hubert after a drawing by M. Mollard. Sparrman was portrayed at an unknown date, but probably in the early 1780s, that is to say, 15 to 20 years before his involvement in textile manufacturing. (Swedish stamp, 1 krona). This is a uniquely preserved document for ‘Professor Mr Sparrman’, which listed various necessary dyes, chemicals and other ingredients for a textile print-work in 1797, with an initial notation in the previous year. The account was added up and signed in Stockholm on 30 December 1797 by the pharmacist/chemist Pehr Gillberg. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This is a uniquely preserved document for ‘Professor Mr Sparrman’, which listed various necessary dyes, chemicals and other ingredients for a textile print-work in 1797, with an initial notation in the previous year. The account was added up and signed in Stockholm on 30 December 1797 by the pharmacist/chemist Pehr Gillberg. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Some purchases for Anders Sparrman’s account above are recognisable as common minerals, chemicals, natural dyes etc., kept in dye works at the time in Sweden. Many of those minerals, from moderately hazardous to highly poisonous, frequently appear in contemporary dye books as indispensable ingredients for textile dyeing, not only for print-works but for natural dyeing of yarn and cloth in general by manufacturers and private households alike. In the list above from 1797, the commodities were written either with a Swedish or Latin name; several of these were evidently imported goods, with the most expensive ones listed as ‘Gum Senegal’ and ‘Gum Arabicum’. Such ‘Gum’ was harvested from various wild-growing trees and regarded as an essential gluelike ingredient when printing on cloth. Other listed purchases were, for instance (in an English translation):

- Salt

- Salpeter

- Nitric acid

- Kermes

- Vitriol

- Sal ammoniac

- Vitriol from Cyprus

- Arsenic

- Verdigris

- Mercury

- Roman alum

- Gum Arabic

- Gum Senegal

- Bottles

- Bottles with glass tops

Notably, in this Järva print-work – where Sparrman was the part owner – they dyed one coloured calico as an additional service. However, materials for dying are pretty scarce in this account, and no other lists of dyes seem to have survived from this particular manufacture. However, some of the most favourable and popular durable natural dyes for textiles at the time included: indigo, woad, dyer’s weed, common madder, safflower, orchil, oak-apple, dyer’s broom and cochineal.

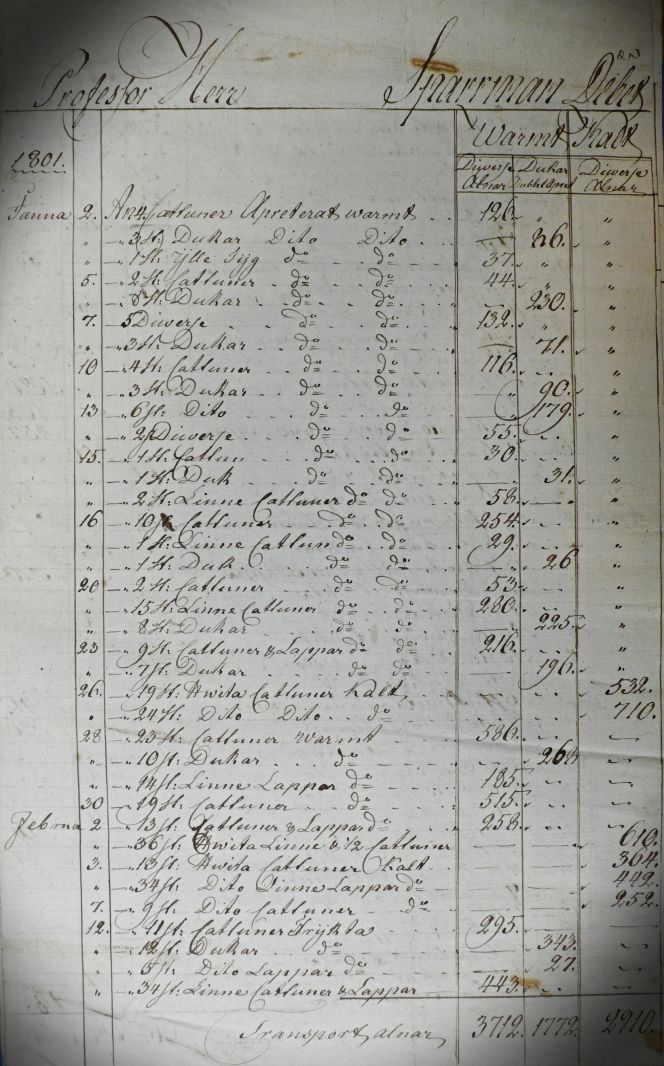

This page for January and part of February in 1801 is part of a preserved document for ‘Professor Mr Sparrman’, which over the pages, listed the various treatments of fabrics during the months of January to September this particular year. See an analyse in a translation below. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This page for January and part of February in 1801 is part of a preserved document for ‘Professor Mr Sparrman’, which over the pages, listed the various treatments of fabrics during the months of January to September this particular year. See an analyse in a translation below. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. The three right-hand columns include information about ‘Warmt’ and ‘Kalt’, that is to say, the number of fabrics recorded to be either finished off and mangled in a ‘warm’ state, assisted by steam or wood burning in contrast to ‘cold’ when it was treated without any heat. The warm column is divided into ‘Various ells’ [≈59 cm long piece of fabric] and ‘Pieces of cloth, double finished’. This finishing made the fabric more glossy, a process which could be chemical or mechanical or a combination of both for the desired result. Judging by the word ‘double’, it appears to have been a two-stage process. The ‘cold’ column listed ‘various ells’ only (on other document pages as ‘white goods’). It may also be noted that the textiles were infrequently mentioned as ‘printed’ throughout this document, dated in 1801. Still, most textiles probably had some printed pattern, excluding the ones listed as ‘white’ or ‘white goods.’ Furthermore, ‘cattuner’ in Swedish could be used equally for plain-woven cotton fabric with and without printed motifs at this time. So even if this unique document reveals a multitude of interesting information, it can undoubtedly be interpreted in more than one way. Anders Sparrman was not the only one who had a financial interest in this textile business, evidenced via signatures on some of the following pages, among those the earlier mentioned manufacturer Stephen Bennet in ‘Järva on 1st May: 1801’.

‘1801

January – 2nd to 30th

- 4 pieces of printed calicoes, warm finishing

- 3 pieces of cloth, ditto ditto

- 1 piece of woollen cloth, ditto ditto

- 2 pieces of printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 8 pieces of cloth, ditto ditto

- 5 pieces of various, ditto ditto

- 3 pieces of cloth, ditto ditto

- 4 pieces of printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 3 pieces of cloth, ditto ditto

- 6 pieces of ditto, ditto ditto

- 2 pieces of various, ditto ditto

- 1 piece of printed calico, ditto ditto

- 1 piece of cloth, ditto ditto

- 2 pieces of linen printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 10 pieces of printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 1 piece of linen printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 1 piece of cloth, ditto ditto

- 2 pieces of printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 15 pieces of linen printed calicoes, ditto ditto

- 8 pieces of cloth, ditto ditto

- 9 pieces of printed calicoes and fabric pieces, ditto ditto

- 7 pieces of cloth

- 19 pieces of white calicoes, cold

- 24 pieces of ditto ditto, ditto

- 23 pieces of printed calicoes, warm

- 10 pieces of cloth, ditto

- 14 linen fabric pieces, ditto

- 19 pieces of printed calicoes, ditto

February – 2nd to 12th

- 13 pieces of printed calicoes & fabric pieces, ditto

- 36 pieces of white linen & 1/2 calicoes, cold

- 13 pieces of white calicoes, ditto

- 34 pieces of ditto linen fabric pieces, ditto

- 9 pieces of ditto printed calicoes, ditto

- 11 pieces of printed calicoes

- 12 pieces of cloth, ditto

- 5 fabric pieces, ditto

- 34 pieces of linen calicoes & fabric pieces

The final page of this document ends on 28th September 1801, when the total number of printed fabrics and white qualities were registered as follows: ‘4679 ells. Double finished’, ‘9323 ells. Simple ditto’ and ‘21210 ells. White goods.’

It has not been possible to trace any printed calicoes from the Järva print-works. Still, this contemporary calico on a white ground with a flowery motif in brown and blue – used as an apron – may be an example of such prints. According to the museum catalogue card, a Stockholm manufacturer probably made the block-printed calico during the 1770s-1790s. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum… NM.0002884. DigitaltMuseum).

It has not been possible to trace any printed calicoes from the Järva print-works. Still, this contemporary calico on a white ground with a flowery motif in brown and blue – used as an apron – may be an example of such prints. According to the museum catalogue card, a Stockholm manufacturer probably made the block-printed calico during the 1770s-1790s. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum… NM.0002884. DigitaltMuseum).

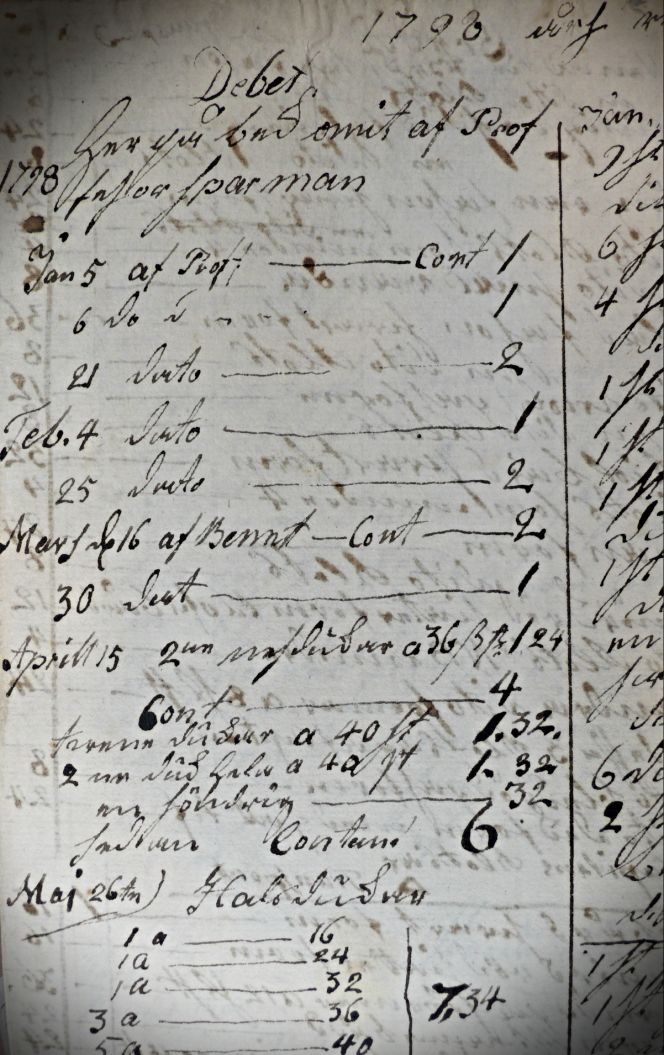

Debit (in the picture) and credit columns in double entry bookkeeping for Järva printing manufacture 1798, referring to ‘Professor Sparrman’, listing cloths and ‘Neckerchiefs’ sold within the operation. This is another example of accounting documents in the National Archive, kept after Anders Sparrman’s and Stephen Bennet’s ownership at the turn of the century 1800. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Debit (in the picture) and credit columns in double entry bookkeeping for Järva printing manufacture 1798, referring to ‘Professor Sparrman’, listing cloths and ‘Neckerchiefs’ sold within the operation. This is another example of accounting documents in the National Archive, kept after Anders Sparrman’s and Stephen Bennet’s ownership at the turn of the century 1800. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. A few further historical observations aim to conclude Sparrman’s continuous path in life. After his return home from long-distance travels to southernmost Africa, New Zealand, Oceanic island regions etc., he travelled to England in order over some months in 1776-77 to arrange the collections from the circumnavigation together with the botanists Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-1798) and his son George Forster (1754-1794) who also had taken part in James Cook’s second voyage. After that, he entered twenty years of employment at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, working with their cabinet of natural history specimens. At the same time, his African travel journal was published in four languages in the 1780s. His stay in the Cape Province gained pioneering significance because of the increased knowledge of its flora, fauna, ethnography and peoples. In 1787-88 he returned once more to Africa, that time to West Africa to Senegal as his destination, and less for reasons of natural history work but rather for the sake of expanding his involvement in the movement for the abolition of the slave trade. His scientific and ethnographical work was often overshadowed by Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828), Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) successor, as he also visited the Cape Province and recorded his stay there in a travel journal. Thunberg was better off, able to publish his findings and extremely productive. Sparrman was in no way either indolent or unproductive, although his image was for a long time that of a less successful apostle. Such negative judgements have been greatly reassessed of late, but what nevertheless has to be taken into account is the fact that he lacked some of the elementary structure and determination in his scientific work which Thunberg possessed. In his more mature years, Sparrman’s priorities seem to have changed: he worked as a physician to the poor and owned textile manufacturers, besides carrying out his tasks of a more academic nature. He also succeeded in publishing his two final volumes covering the circumnavigation, thereby completing the series in 1802 and 1818, respectively. The former Carl Linnaeus apostle proved himself to be a highly multifaceted polymath over his lifetime.

Notice: The illustrated original documents have been transcribed and translated into English by the author of this essay.

Sources:

- Broberg, Gunnar, Dunér, David & Moberg, Roland, ed., Anders Sparrman – Linnean, Världsresenär, Fattigläkare, Uppsala 2012 (Historical facts about Sparrman’s life in several articles & Quote in translation p. 233).

- Hansen, Lars, ed. The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, 8 vol., London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Anders Sparrman: Vol. Five. Journal & Vol. Eight. Biography: pp. 43-45).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Anders Sparrman’s chapter, pp. 227-252. See this book for other aspects of his textile observations. & Full notes and bibliography, pp. 452-482).

- Henschen Ingegerd, (ed. Ingrid Frankow), Kattuntryck – Svenskt tygtryck 1720-1850, Stockholm 1992 (quote in translation p. 76).

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943 (quote in translation p. 750).

- The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm, Sweden. Bennet Family Archive (Bennetska Släktarkivet). Manuscript connected to Anders Sparrman 1797-1802. | Research visit in 2014.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. (Information on catalogue card; about the illustrated printed calico apron. NM.0002884 DigitaltMuseum).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE