ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

NEW ZEALAND FLAX CLOAKS IN THE 1770s

– Observations by Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander et al.

The botanist and naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) belonged to a group of well-known British individuals of the late 18th and early 19th century. His travel journal from James Cook’s first voyage has been published in full, he was portrayed numerous times and was a long-lived president of the Royal Society. Diverse correspondence has been preserved, and a wide range of research has focused attention on his life and work to this day. My monograph Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade also includes observations related to Banks. Primarily due to his long friendship with Daniel Solander and their mutual scientific journeys. This essay will focus on the finely produced New Zealand flax cloaks, assisted by a few informative images and further thoughts on material culture from this area.

This portrait of Joseph Banks dated 1773 was made a few years after the return from James Cook’s first voyage – when Banks, Cook, Daniel Solander et al collected/bartered numerous items for everyday and festive uses during their stay in New Zealand. Banks wears a cape made of New Zealand flax fibre, along with botanical books, weapons and other implements from the voyage in 1768 to 1771. Probably due to demonstrate his successful scientific long-distance travel, supplemented with suitable attributes from far-flung countries. It may also be noted that all minute details of the cloak etc are more distinct in this mezzotint, than on the original oil on canvas from the same year. (Courtesy of: The British Museum, No: 1841,0809.150, Online Collection. Portrait after Benjamin West, Staley 586; Usher Gallery, Lincoln).

This portrait of Joseph Banks dated 1773 was made a few years after the return from James Cook’s first voyage – when Banks, Cook, Daniel Solander et al collected/bartered numerous items for everyday and festive uses during their stay in New Zealand. Banks wears a cape made of New Zealand flax fibre, along with botanical books, weapons and other implements from the voyage in 1768 to 1771. Probably due to demonstrate his successful scientific long-distance travel, supplemented with suitable attributes from far-flung countries. It may also be noted that all minute details of the cloak etc are more distinct in this mezzotint, than on the original oil on canvas from the same year. (Courtesy of: The British Museum, No: 1841,0809.150, Online Collection. Portrait after Benjamin West, Staley 586; Usher Gallery, Lincoln).From October 1769 to March 1770, James Cook’s first circumnavigation sailed in the waters and visited the islands of New Zealand. From a European perspective, this stay was fruitful and foremost aimed at discovery, exploration as well as cartography. The clothes of the local people and their production formed a subject of interest for the journal writers Banks, Cook and the artist Sydney Parkinson, and of which Daniel Solander too must have been aware even if not keeping a journal. Parkinson noted down four descriptions of the North Island and, in addition, several drawings showing how the New Zealand warriors were attired and adorned; particularly decorative and informative is the illustration below of a warrior dressed in a large cloak demonstrating his high status.

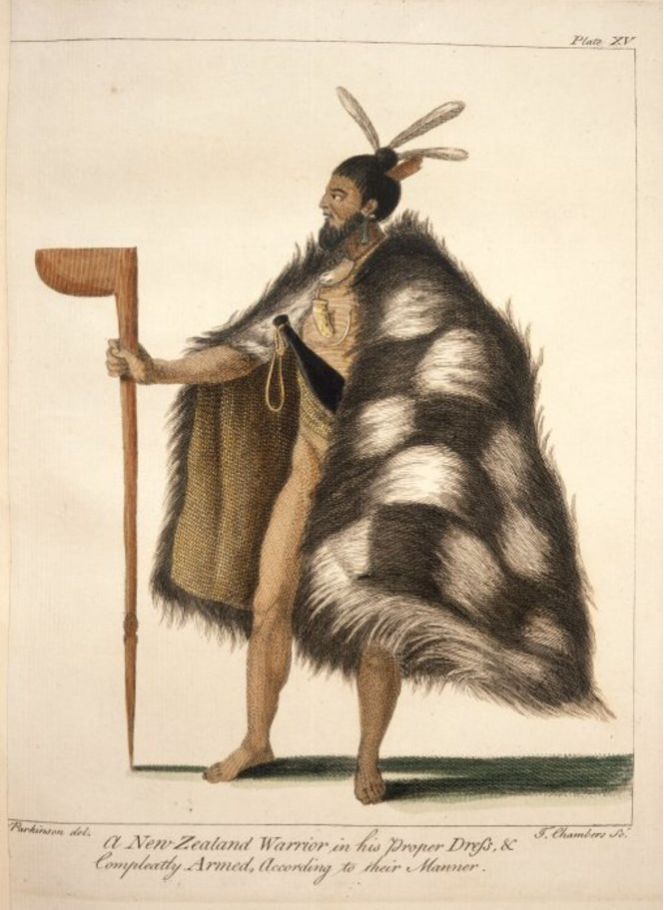

A similar type of New Zealand cloak, differing in the way that the entire garment was made of dog fur and only lined with the traditionally made New Zealand flax fibre fabric. Mentioned as Plate XV. ‘A New Zealand Warrior in his Proper Dress, & Compleatly Armed, According to their Manner’ in Sydney Parkinson’s travel journal. Among several others in the crew, the young artist Parkinson died during the homeward leg of the voyage in January 1771 and his journal was published posthumously in 1784. (From: Parkinson, Sydney, A Journal of a voyage to the south seas in his Majesty’s ship The Endeavour, p. 124).

A similar type of New Zealand cloak, differing in the way that the entire garment was made of dog fur and only lined with the traditionally made New Zealand flax fibre fabric. Mentioned as Plate XV. ‘A New Zealand Warrior in his Proper Dress, & Compleatly Armed, According to their Manner’ in Sydney Parkinson’s travel journal. Among several others in the crew, the young artist Parkinson died during the homeward leg of the voyage in January 1771 and his journal was published posthumously in 1784. (From: Parkinson, Sydney, A Journal of a voyage to the south seas in his Majesty’s ship The Endeavour, p. 124).Apart from that, a large part of the population was dressed in plaited grass garments in the shape of cloaks, loincloths, and skirts, which were produced with great craftsmanship. As distinguished from the inhabitants of the Society Islands, the islanders here did have knowledge of the weaving/plaiting of cloth, which, according to Parkinson, was made from a shiny white silk-like yarn. The fabrics were chiefly worn by the men, but made by the women and might even comprise coloured details, described as follows in October 1769: ‘The man, who seemed to be the chief, had a new garment, made of the white silky flax, which was very strong and thick, with a beautiful border of black, red, and white round it.’ Otherwise, there was nothing written by the three diarists about the dyeing of cloth, which is probably because the textiles were always described as white except for coloured borders.

The weft-twining techniques of the region were worked with the aid of weaving sticks and hands, and depending on the skill of the weaver, some very fine and complex textiles could be produced. Banks also noted that ‘Weaving and the rest of the arts of peace are best known and most practised in the North Eastern parts; indeed, in the Southern region, there is little to be seen of any of them’. This is yet another observation of the North Islanders’ crafts and cultural traditions being further developed than those on the South Island. Banks’ lengthy summary of the Maoris’ clothing provide some minor additions: their garments of grass were seen through a European’s eyes as ‘very ugly’, though well adapted for people who sleep outdoors and cover themselves with a cloak in all weathers. The finer fabrics of flax, which shone like silk, were much admired by Banks, however, primarily the beautifully finished borders in different colours of a weft-twining technique – as may be studied on the two images below of a well-preserved cloak.

Finely made cloak, in a weft-twining technique from New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax). The exclusive garment, intended for a man of high social status was acquired around 1770. At the time as Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander stayed in New Zealand along with James Cook and the rest of the travelling group, or during Cook’s second or third voyages in the same area. Notice that this cloak differs slightly from the garments worn by Joseph Bank and the New Zealand warrior on the portraits above. Furthermore, at least 40 Maori capes of that kind with or without dog fur details, and maybe more, were transported to Europe from Cook’s circumnavigations. (Courtesy of: The British Museum, no. Oc,NZ.137. ‘Cloak (kaitaka) of the patea type’. Collection Online).

Finely made cloak, in a weft-twining technique from New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax). The exclusive garment, intended for a man of high social status was acquired around 1770. At the time as Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander stayed in New Zealand along with James Cook and the rest of the travelling group, or during Cook’s second or third voyages in the same area. Notice that this cloak differs slightly from the garments worn by Joseph Bank and the New Zealand warrior on the portraits above. Furthermore, at least 40 Maori capes of that kind with or without dog fur details, and maybe more, were transported to Europe from Cook’s circumnavigations. (Courtesy of: The British Museum, no. Oc,NZ.137. ‘Cloak (kaitaka) of the patea type’. Collection Online). Close-up detail of a complex border of the same New Zealand flax cloak, dating ca 1770 (Courtesy of: The British Museum, no. Oc,NZ.137, detail. Collection Online).

Close-up detail of a complex border of the same New Zealand flax cloak, dating ca 1770 (Courtesy of: The British Museum, no. Oc,NZ.137, detail. Collection Online).Notice: This essay only touches upon the variations of the complex weft-twining techniques and their history. More information about: ‘Techniques for weaving Māori cloaks’ (online resource) by the Museum of New Zealand.

Sources:

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771, Cambridge 1952.

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed. The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771, 2 vol, Sydney 1963.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007- 2012 (Vol. Seven: Ch. of Daniel Solander).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 215-218).

- Parkinson, Sydney, A Journal of a voyage to the south seas in his Majesty’s ship The Endeavour, London 1784.

- The British Museum, Online Collection (Joseph Bank's Portrait and New Zealand Cloak).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE