ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

PEHR KALM’S TEXTILE OBSERVATIONS

– in London and surrounding Counties 1748

The naturalist’s observations from a textile perspective foremost included trade with cloth, natural dyeing of yarn and fabric, raw materials, spinning and weaving, textiles for interior use and bed linen, fashion and personal travel clothes. This essay is based on the former Carl Linnaeus student Pehr Kalm’s journal and travelling account kept in England in 1748, as researched via my project “Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th century Textile Traditions & Trade”.

This oil on canvas by Canaletto (c. 1750-51) shows parts of London as Kalm mentioned several times in his journal; particularly the Thames on which he both arrived and departed on by ship, how the Londoners were dressed, St Paul’s Cathedral and the city’s many church towers. However Kalm’s notes gives a drab impression compared to the painting’s brightness, for example he noted on 19 April 1748: ‘Around noon I went up into the church tower of St Paul’s with Mr Warner and Captain Shierman to see the view from there around London… From its uppermost gallery one would have had a beautiful view in all directions, if only the air had been clear; but the thick coal smoke that hung over the city on every side obstructed the view in a number of places; from here one could count quite a large number of churches here in London, namely a few more than sixty, that is to say those that had towers and could be distinguished from other large buildings…’(Courtesy of: Royal Collection, London. Google Art Project).

This oil on canvas by Canaletto (c. 1750-51) shows parts of London as Kalm mentioned several times in his journal; particularly the Thames on which he both arrived and departed on by ship, how the Londoners were dressed, St Paul’s Cathedral and the city’s many church towers. However Kalm’s notes gives a drab impression compared to the painting’s brightness, for example he noted on 19 April 1748: ‘Around noon I went up into the church tower of St Paul’s with Mr Warner and Captain Shierman to see the view from there around London… From its uppermost gallery one would have had a beautiful view in all directions, if only the air had been clear; but the thick coal smoke that hung over the city on every side obstructed the view in a number of places; from here one could count quite a large number of churches here in London, namely a few more than sixty, that is to say those that had towers and could be distinguished from other large buildings…’(Courtesy of: Royal Collection, London. Google Art Project).Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) was enrolled at Uppsala University in 1740 and there he was soon regarded as one of Carl Linnaeus’ most promising students. Despite not having defended his thesis for the doctorate, he was elected to The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1745 and the following year he was appointed university lecturer at Åbo Academy. A period of thinking and discussion of an economic nature seems to have passed before Kalm had the possibility to set out on his long journey to North America; surviving correspondence suggests that he even contemplated travelling to other distant and unexplored places. All issues and financial doubts were, however, resolved in 1747, and the North American journey could begin almost simultaneously with his being granted a sought-after professorial chair at Åbo with the title of ‘Oeconomiae Professor’.

With his assistant Lars Jungström, Kalm departed in October 1747 from Uppland, via Göteborg and Norway to England. Everywhere they passed through had something of interest to be noted, particularly in England, where the group stayed for about six months. Besides ‘utilities’ being observed, the beauty of the countryside, the gardens and the architecture were also admired. He diligently described their transports on land and at sea, the way they were quartered, the collecting of flora and fauna, the people’s manners and customs, and he often drew comparisons with Swedish circumstances.

Oil on canvas, signed J. G. Geitel, c. 1764, some uncertainty remains if the portrait depicts Pehr Kalm. (Courtesy of: Satakunta Museum, Björneborg, Finland).

Oil on canvas, signed J. G. Geitel, c. 1764, some uncertainty remains if the portrait depicts Pehr Kalm. (Courtesy of: Satakunta Museum, Björneborg, Finland).Spinning and Weaving: Although arguably a common domestic activity in England in the mid-1700s, spinning was by no means customary in all areas, which can be seen from two places in Kalm’s travel journal from Bedfordshire on 11th April 1748: ‘Weaving and spinning is also a rare thing among the majority, as their many manufactories liberate them from such matters.’ Furthermore, from Hertfordshire three days later: ‘…for in this area the women do not get sore fingers from much spinning or backache from weaving; it is the manufactories that have to provide all that…’

Bedlinen and filling material: It is also possible to form a pretty clear picture of the bedclothes Kalm used on his journey from his travel expense account. In this detailed list, was recorded day by day what he had spent on himself and his assistant. In London, their bedclothes had initially had to be renewed, and notes show that the fabrics were bought new at the time of their departure for America, bearing in mind that 3d. was paid ‘to the person who carried the bedclothes on board.’ Listed at the same time was a purchase of a feather-bed, pillow, blanket and quilt for himself for a total of 20 shillings, so that he may keep warm during the journey. In addition, bedclothes for his assistant Jungström were procured for the sum of 7 shillings, probably of a simpler kind.

Trade in yarn, socks and fabric: There were also some entries in Kalm’s travel expense account which report or indicate whence the cloth and yarn originated. On arrival in England he bought first of all ‘brown Holland for 4 cuffed shirts’, which was considered to be the finest linen there was to buy – a Dutch import, in other words, and much coveted on the English market. Kalm also obtained several other wardrobe items during his stay in London, but the materials here were silk and cotton instead. The raw material for those items would most likely have been imported into the country, while the spinning and weaving would have been done in England. His purchases consisted mainly of handkerchiefs of cotton and silk, a silk scarf for his assistant, Jungström, and silk ribbons. On his return to Sweden in the spring of 1751, however, Kalm bought a ‘Striped Linen handkerchief’, something which may indicate that it was more difficult to get hold of silk fabrics in his native country, owing to import restrictions, and the indigenous linen fabrics therefore being more widely used.

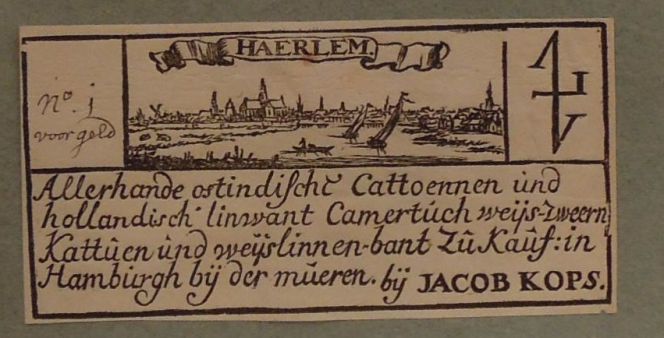

An alternative to that Kalm’s purchased fabrics of silk and cotton had been woven in England could be import via the East Indian trade (with the exception of printed cottons prohibited to import 1700-74). This trade label from Hamburg shows a comparable relation of trade as London’s; both in connection to the considerable Dutch production and export of fine linen materials in 18th century Europe – like the ‘brown holland’ fabric acquired by Kalm – as well as the East Indian cottons which were highly desired goods in many countries. The trade label reads in translation: ‘All kinds of East Indian cottons and Dutch linen cambric, linen goods, calico and white-linen tape for sale: in Hamburg by the wall, at Jacob Kops.’ (Courtesy of: Princeton rare book collection, No. NC1002.L3V56f, vol. 2, leaf 19.)

An alternative to that Kalm’s purchased fabrics of silk and cotton had been woven in England could be import via the East Indian trade (with the exception of printed cottons prohibited to import 1700-74). This trade label from Hamburg shows a comparable relation of trade as London’s; both in connection to the considerable Dutch production and export of fine linen materials in 18th century Europe – like the ‘brown holland’ fabric acquired by Kalm – as well as the East Indian cottons which were highly desired goods in many countries. The trade label reads in translation: ‘All kinds of East Indian cottons and Dutch linen cambric, linen goods, calico and white-linen tape for sale: in Hamburg by the wall, at Jacob Kops.’ (Courtesy of: Princeton rare book collection, No. NC1002.L3V56f, vol. 2, leaf 19.)Materials for clothing in England; It was mainly the women’s clothes which attracted his attention, both when Kalm travelled around the south of England and during his stay in the capital. What surprised him was that their everyday existence seemed to pass in much more comfortable circumstances than was the case for the Swedish peasants’ wives. Particularly as the cottage industry was already beginning to take over the textile production on a large scale that meant that the women rarely had to devote themselves to such time-consuming activities as spinning and weaving. Their dress was, therefore, not so specific to the locality as in Sweden, and even the peasants’ wives and daughters were dressed according to the fashion of the day, both as to cut and material. Delicate quality woollen and linen fabrics were predominantly the choice of material for their costumes. There was no need for them to bake as there was a baker in every village, and at the same time, they were relieved of any form of outdoor work in fields and meadows – an altogether more comfortable existence, according to Kalm’s observations. Their actual daily activities consisted instead of cooking, cleaning, scrubbing, washing, knitting socks and making and embroidering linen garments. In April 1748, their way of dressing was further recorded: ‘One does not see hoop-petticoats used here in the countryside. When they go out they always wear straw hats, which they themselves make here from wheat straw, and they are quite attractive. On festive days they wear cuffs.’ It was also put on record that the peasant women may have been dressed like Swedish gentlewomen, but the ladies of London were even more elegant. What most of all caught his eye, however, were the beautiful hats which were made of horsehair, black silk or finely plaited straw. From a walk around St Paul’s Cathedral in the same month it was noted: ‘The women in this locality wore hats that were made of snow-white horsehair and looked extremely handsome.’

On the 8 June 1748 Kalm noted in his journal: ‘Almost all English women, both married and unmarried, used stays, lacing themselves up tightly, so that they looked very slim, especially as long as they were young and unmarried… During the winter one saw relatively few of them using hooped petticoats while walking on the streets of London; but now in the summer the hoop-petticoat was an everyday garment for most of them, especially when they were going out…’ This observation of the female dress has great resemblance with Thomas Gainsborough’s (1727-1788) oil on canvas “Portrait of Woman” from c. 1750. A study of the artist’s collection of portraits also point in the direction that he already at a young age developed an eye for details in fashion, textile materials and how the garment hangs on the body. Most probably due to the fact that his father John Gainsborough worked as a weaver and woollen merchant. (Courtesy of: Yale Center for British Art, USA. Google Art Project).

On the 8 June 1748 Kalm noted in his journal: ‘Almost all English women, both married and unmarried, used stays, lacing themselves up tightly, so that they looked very slim, especially as long as they were young and unmarried… During the winter one saw relatively few of them using hooped petticoats while walking on the streets of London; but now in the summer the hoop-petticoat was an everyday garment for most of them, especially when they were going out…’ This observation of the female dress has great resemblance with Thomas Gainsborough’s (1727-1788) oil on canvas “Portrait of Woman” from c. 1750. A study of the artist’s collection of portraits also point in the direction that he already at a young age developed an eye for details in fashion, textile materials and how the garment hangs on the body. Most probably due to the fact that his father John Gainsborough worked as a weaver and woollen merchant. (Courtesy of: Yale Center for British Art, USA. Google Art Project).Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, Volume Three: Book One (Kalm’s journal/England), London & Whitby 2008.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th-century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (research material, pre-publishing).

- Kalm, Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland, Helsingfors 1956.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE