ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

PLANTÆ TINCTORIÆ

– A Dissertation in 1759 and Carl Linnaeus’ Observations of Natural Dyes

Who wrote a dissertation in the 18th century is not seldom debatable and may be cause for confusion. Plantæ Tinctoriæ is no exception, even if it, in my view, can be regarded as evidence that the student Engelbert Jörlin (1733-1810), whose name was printed on the front page, mainly defended a Latin dissertation based on his professor’s longterm work on the subject. The author was, therefore, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the first printed name, as the dissertation was mainly based on his previous observations and published volumes with notes on textile dyeing. Like in most dye books and travel observations on this issue in the 18th century, yellow shades have a prominent place – while this small print in total lists about 130 plants and insects, giving a wide range of durable colours on wool, silk and linen. The main aim of this essay is to reveal rarely looked-at details about this Latin dissertation, thoughts on authorship, Linnaeus’ long-term interest in textile dyeing, and a few other reflections on the domestic uses and international trade concerning natural dyes.

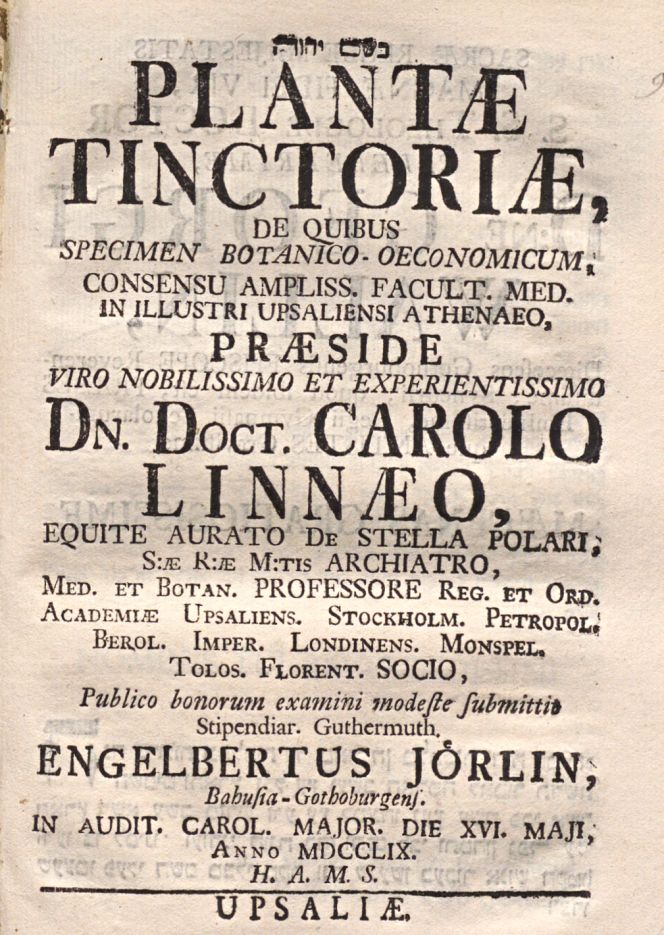

Front page of the 30-page dissertation Plantaæ Tinctoriæ…, dated 16th May 1759. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).

Front page of the 30-page dissertation Plantaæ Tinctoriæ…, dated 16th May 1759. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).A note about these 18th century Swedish dissertations has been emphasised in the following words by the historian of science Gunnar Eriksson: ’The title page always stated who presided – a person with the title of professor, senior lecturer or master – in several cases Carl Linnaeus figures among these. The respondent, on the other hand, defended the dissertation. Which one of the two had written the text can, at times, be questionable. The dissertations varied in size between two and 150 pages.’ However, the professor or senior lecturer most often wrote the dissertation. According to my in-depth studies of natural dyeing in the 18th century and by looking closer at Plantæ Tinctoriæ, this is also true for this small print. Foremost due to that, the material had already been observed and published in several botanical works and travel journals by Linnaeus over more than twenty years, whilst the respondent Engelbert Jörlin only defended the Latin dissertation, which was a requirement for students. Informative biographical facts about Jörlin’s life also inform that he defended his dissertation ‘pro exercitio’, a term which intended to show that the student could defend it in Latin. It is noticeable, too, that the relatively mature student Jörlin, at the age of 24, was enrolled at Uppsala University on the 20th of September 1757. That is to say, less than two years before the date stated on the publication of Plantæ Tinctoriæ, 16th May 1759, which makes it even more unlikely that the student was the actual author of this very detailed knowledge, which gives information about 130 different plants and insects suitable for textile dyeing, together with a few suggestions of plants, which were used for the laundry of linen. The cited works were foremost Linnaeus’ earlier publications, his former student Pehr Kalm (1716-1778), a dye book by Johan Linder (1676-1724), and a few other sources. Furthermore, first ten years later, in 1769, Jörlin became a docent in botany at Lund University after his student years and journeys abroad.

The naturalist Carl Linnaeus was fascinated by textile materials from an economical and practical point of view. He also demonstrated equally strongly through his botanical research what a vital role dye plants played for the people of the time. The ability to choose the correct plant types for dyeing woollen yarn was mainly a tradition handed down by word of mouth in the different regions. Such local customs, often aged, represented a wealth of knowledge as to which parts of the plant were the most advantageous to use in terms of both the beauty of the colour of the dyed yarn and its durability when washed and exposed to light. The dyeing recipes were, moreover, often deeply embedded in secrecy, something the physician and botanist Johan Linder experienced when he tried to gather information for his book Swenska färgekonst (The Swedish Art of Dyeing), published in 1720. Linnaeus’ observations were made more accessible during his provincial journeys because he visited the various villages, farms, and dye works in person and was able to pose questions directly to the women dyers in their homes as well as to the artisans within the dyeing trade.

![Page 12 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ exemplifies plants that yielded durable yellow dyes; some species could give two different colours depending on which part was used, like the flowers of the ’11. Galium verum’ [Lady’s bedstraw] gives a yellowish shade whilst the roots dye red. Or the ‘5. Crocus sativus’ [Saffron] a plant not hardy in Sweden but cultivated in warmer climes in southern Europe, among other places, from which part of the pistils gives a beautiful yellow colour. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2a-plantae-tinctoriae-664x891.jpg) Page 12 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ exemplifies plants that yielded durable yellow dyes; some species could give two different colours depending on which part was used, like the flowers of the ’11. Galium verum’ [Lady’s bedstraw] gives a yellowish shade whilst the roots dye red. Or the ‘5. Crocus sativus’ [Saffron] a plant not hardy in Sweden but cultivated in warmer climes in southern Europe, among other places, from which part of the pistils gives a beautiful yellow colour. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).

Page 12 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ exemplifies plants that yielded durable yellow dyes; some species could give two different colours depending on which part was used, like the flowers of the ’11. Galium verum’ [Lady’s bedstraw] gives a yellowish shade whilst the roots dye red. Or the ‘5. Crocus sativus’ [Saffron] a plant not hardy in Sweden but cultivated in warmer climes in southern Europe, among other places, from which part of the pistils gives a beautiful yellow colour. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).Linnaeus also succeeded in recording recipes, dye plants and other aspects of the subject during his provincial tours. There is, however, a clear difference between the early journeys of his youth to Lapland in 1732 and Dalarna in 1734 and his assignments in Öland and Gotland, Västergötland and Skåne in the 1740s. The early period is characterised by general descriptions of events and objects; dyeing as such was not prioritised and, therefore, poorly represented. In his Dalaresan (Journey in Dalarna), it was noted, for example, on 30th July, that people wore ‘a red summer jacket ’ and ‘a black summer shirt ’, but no word of how those colours had been produced. Whereas during his three subsequent journeys, such matters were studied in a spirit of the optimistic socio-economic belief that anything could be produced within the country at the same time as research into dye plants formed part of the mission set by the members of the country’s Four Estates. That meant the dyeing of wool, yarn, and fabrics was an essential element, meticulously described in great detail on all his later journeys. He also took the opportunity to emphasise and encourage the cultivation of good dye plants in the various places where such grew in abundance.

Using the roots of bedstraws for natural dyeing has been common knowledge, even though they yielded less bright red colours than common madder. Apart from dyer’s woodruff, that was also the case with northern bedstraw (Galium boreale) and, to an extent, yellow bedstraw (Galium verum), which were very common in dry meadows, on verges and edges of fields in the whole of the country—listed as numbers 10 and 11 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ in the image above. The abundant supply was significant in the circumstances, as collecting roots was laborious. Besides, considerably larger quantities were needed for the two “weaker dyestuffs” than when using common madder or Dyer’s woodruff. Illustrated here are the flowering creamy white northern bedstraw, picked in early July, its root and woollen yarn, dyed red from a first and second dye-bath, mordanted with alum. | Natural dyed wool with northern bedstraw (plant picked in July) Småland, Sweden, by the author of this essay. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Using the roots of bedstraws for natural dyeing has been common knowledge, even though they yielded less bright red colours than common madder. Apart from dyer’s woodruff, that was also the case with northern bedstraw (Galium boreale) and, to an extent, yellow bedstraw (Galium verum), which were very common in dry meadows, on verges and edges of fields in the whole of the country—listed as numbers 10 and 11 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ in the image above. The abundant supply was significant in the circumstances, as collecting roots was laborious. Besides, considerably larger quantities were needed for the two “weaker dyestuffs” than when using common madder or Dyer’s woodruff. Illustrated here are the flowering creamy white northern bedstraw, picked in early July, its root and woollen yarn, dyed red from a first and second dye-bath, mordanted with alum. | Natural dyed wool with northern bedstraw (plant picked in July) Småland, Sweden, by the author of this essay. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).![Page 25 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes the trees ’76. Betula alba’ [Birch] and ’77. Betula nana’ [Dwarf birch], whose leaves give durable yellow dyes on wool. This native species in Sweden was, therefore, precious for dyers in many areas due to the abundance of leaves over many months of the year compared to many other rare dye plants, which were possible to use roots only or had to be acquired via costly imports. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4a-plantae-tinctoriae-664x865.jpg) Page 25 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes the trees ’76. Betula alba’ [Birch] and ’77. Betula nana’ [Dwarf birch], whose leaves give durable yellow dyes on wool. This native species in Sweden was, therefore, precious for dyers in many areas due to the abundance of leaves over many months of the year compared to many other rare dye plants, which were possible to use roots only or had to be acquired via costly imports. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).

Page 25 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes the trees ’76. Betula alba’ [Birch] and ’77. Betula nana’ [Dwarf birch], whose leaves give durable yellow dyes on wool. This native species in Sweden was, therefore, precious for dyers in many areas due to the abundance of leaves over many months of the year compared to many other rare dye plants, which were possible to use roots only or had to be acquired via costly imports. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).It is noticeable that all of Linnaeus’ journals from his provincial tours mentioned textile dyeing, as did his Flora Oeconomica and Flora Svecica/Svensk Flora, each containing between 35 and 40 plants, described as suitable for dyeing. Many of the plants noted keep reappearing in several of Linnaeus’ publications, especially the well-known and most used ones. At the same time, some rarer species, or species unlikely to serve the purpose of dyeing, are only mentioned on one occasion. This section will also deal with the dyeing of textile materials from various aspects, including quotations from the regions visited. To each provincial description is also added an analysis of the dyes that were used and suggested, as recorded from the different areas, together with a closer look into those methods of textile dyeing. Due to the fact that the journeys were undertaken either before or during the time when the homogeneous classification of plants was being implemented, it must be borne in mind that the same plant appeared under different names at times. The sexual system with its binomial nomenclature, with names of genera and species, was only fully systemised in the second edition of Linnaeus’ Flora Svecica of 1755.

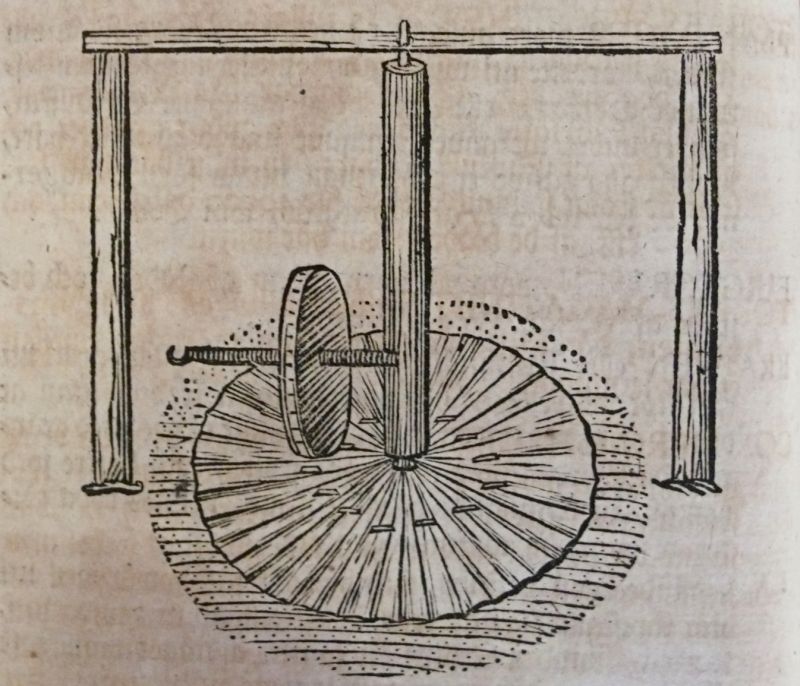

![Page 21 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes both ’58. Isatis tinctoria’ [woad] and ’59. Indigofera tinctoria’ [indigo], which both gave durable blue colours. Woad was cultivated in Sweden and imported, whilst dried indigo was always traded in complex global trade networks. Interestingly, Linnaeus even illustrated a woad mill in his publication about the Västergötland Journey, which took place in 1746. See the illustration below and his observations about the extensive storage of desirable dyes at a dyeing manufacturer. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5a-plantae-tinctoria-664x919.jpg) Page 21 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes both ’58. Isatis tinctoria’ [woad] and ’59. Indigofera tinctoria’ [indigo], which both gave durable blue colours. Woad was cultivated in Sweden and imported, whilst dried indigo was always traded in complex global trade networks. Interestingly, Linnaeus even illustrated a woad mill in his publication about the Västergötland Journey, which took place in 1746. See the illustration below and his observations about the extensive storage of desirable dyes at a dyeing manufacturer. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book).

Page 21 in Plantæ Tinctoriæ includes both ’58. Isatis tinctoria’ [woad] and ’59. Indigofera tinctoria’ [indigo], which both gave durable blue colours. Woad was cultivated in Sweden and imported, whilst dried indigo was always traded in complex global trade networks. Interestingly, Linnaeus even illustrated a woad mill in his publication about the Västergötland Journey, which took place in 1746. See the illustration below and his observations about the extensive storage of desirable dyes at a dyeing manufacturer. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden. Digitised book). The woad mill was described and illustrated in Linnaeus’ Västergötland Journey 1746. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning..., Stockholm, 1747 (p. 128).

The woad mill was described and illustrated in Linnaeus’ Västergötland Journey 1746. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning..., Stockholm, 1747 (p. 128).  A closeup photograph of the woad leaves (Isatis tinctoria), which were ground in the woad mill, indispensable for shades of blue for dye-works as well as domestic dyers, especially if, like Linnaeus and other self-sufficiency proponents of the Age of Liberty, one wished to minimise the import of indigo. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London – in Fredriksdal Botanical Garden in May, Helsingborg, Sweden.

A closeup photograph of the woad leaves (Isatis tinctoria), which were ground in the woad mill, indispensable for shades of blue for dye-works as well as domestic dyers, especially if, like Linnaeus and other self-sufficiency proponents of the Age of Liberty, one wished to minimise the import of indigo. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London – in Fredriksdal Botanical Garden in May, Helsingborg, Sweden.That Carl Linnaeus and his contemporaries were fervent advocates of the excellent qualities of domestically grown plants for dyeing did not exclude the existence of imported alternatives. Jonas Alström’s (1685-1761) enterprise is the most evident proof of that in Linnaeus’ notes from his Västergötland journey. The storehouses of the manufacture are described as being filled with dyes and dye-grass, a considerable part of which was imported, such as ‘brazil-wood, sappan, Pernambuco, yellow-wood, campeachy wood, wood from Versecz, Japanese wood, weld (French and Swedish), orchil, litmus, woad (English, French, [Thuringian] from Erfurt, Swedish; the two latter equally good and the best), indigo, common madder, sumach, pomegranate peel, laurel berries, oak-apple, cochineal, acorns from a certain species of oak and Spanish pepper’ (7 July 1746). Whoever reads the journal is told how dyer’s weed and woad were bought in from France, plants which were often pointed out as being well capable of tolerating the Swedish climate. Parts of the store of woad originated from England, whereas dyestuffs such as cochineal, indigo, sumach and brazil-wood originated in distant lands. The East India Companies formed an essential link in that context, not only the Swedish company but also the other European companies which carried out trade both directly with the East Indies and together via the Spanish Empire had the monopoly of the exchange of goods in dyestuffs from its colonies in South America. The merchants and their partners at different levels made good business deals, but the mystery-making and secrecy surrounding it all were of striking dimensions.

Sources:

- Eriksson, Gunnar, ‘Clergyman or Physician’, The Linnaeus Apostles: Global Science & Adventure, Ed. Lars Hansen. Vol. One, pp. 181-196 (quote p. 195).

- Franzen, Olle, Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Volume 20, p. 555 (Engelbert Jörlin, biographical facts).

- Hansen, Viveka (Practical experiments in natural dyeing).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Read more about Carl Linnaeus’ observations about natural dyeing: pp. 345-387 & 424-435).

- Hofmann-de Keijzer, R.; de Keijzer, M. ‘Plantae tinctoriae: The 1759 Dissertation on Dye Plants by Engelbert Jörlin’. Heritage 2023, 6, 1502–1530.

- Kalm, Pehr, ‘Förteckning på någre inhemska Färgegräs.’ Kungliga Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar. (KVAH) vol 6. pp. 243-253, 1745.

- Linder [Lindestolpe], Johan, Swenska färgekonst, 1720.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Svensk Flora – Flora Svecica, Stockholm 1755.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Plantæ Tinctoriæ…, Uppsala 1759.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Flora Oeconomica (1737), Uppsala, facsimile 1971 (alder bark no. 775. B).

- Nordisk Familjebok, Volume 13, p. 499 (Jörlin, Engelbert), Stockholm 1910.

- Sandberg, Gösta, & Sisefsky, Jan, Växtfärgning, Stockholm 1979.

- Uppsala University Library, Medicine and Pharmaceutical Science Department, Sweden (Digitised original of the publication Plantæ Tinctoriæ…).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE