ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

POLLUTION AND HEALTH

– Textile Observations by 18th Century Naturalists

Nature was full of poisonous plants and animals in the 18th century, just as today. In addition to these natural dangers, artificial hazards arose when humans, to a more significant extent, even before industrialisation, started to mine or extract coal, lead, arsenic and asbestos – aspects which early observers noted to be a disadvantage for people, animals and the environment. From a textile perspective, during the 1740s to 1790s, these issues foremost focused on the dyeing of cloth and yarn, finding new functional raw materials, washing becoming black dotted outdoors and ship sails being brittle. This essay looks closer at such observations by Carl Linnaeus, his apostles and other naturalists in their network – in Sweden, England, the North American colonies and Japan. However, judging by the researched travel journals etc., originating in the naturalists’ observations in more than 50 countries, it may still be regarded as unusual to mention air pollution or the risks of mineral extractions in any form.

This oil on canvas, named ‘The Thames from the Terrace of Somerset House, Looking toward Westminster’ painted circa 1750, shows parts of London as the naturalist Pehr Kalm mentioned several times in his journal. Particularly the Thames with the bustling traffic on which he both arrived and departed by ship, how the Londoners were dressed and the Westminster Bridge. Even so, Kalm’s notes give a drab impression compared to this painting’s hazy brightness. For example, one of his notes about the troublesome coal smoke in London was on 19th April 1748: ‘Around noon I went up into the church tower of St Paul’s with Mr Warner and Captain Shierman to see the view from there around London... From its uppermost gallery, one would have had a beautiful view in all directions if only the air had been clear; but the thick coal smoke that hung over the city on every side obstructed the view in a number of places; from here, one could count quite a large number of churches here in London, namely a few more than sixty, that is to say, those that had towers and could be distinguished from other large buildings…’ (Courtesy: Yale Center for British Art. YCBA/lido-TMS-320. Painting by Canaletto (1697-1768). Public Domain).

This oil on canvas, named ‘The Thames from the Terrace of Somerset House, Looking toward Westminster’ painted circa 1750, shows parts of London as the naturalist Pehr Kalm mentioned several times in his journal. Particularly the Thames with the bustling traffic on which he both arrived and departed by ship, how the Londoners were dressed and the Westminster Bridge. Even so, Kalm’s notes give a drab impression compared to this painting’s hazy brightness. For example, one of his notes about the troublesome coal smoke in London was on 19th April 1748: ‘Around noon I went up into the church tower of St Paul’s with Mr Warner and Captain Shierman to see the view from there around London... From its uppermost gallery, one would have had a beautiful view in all directions if only the air had been clear; but the thick coal smoke that hung over the city on every side obstructed the view in a number of places; from here, one could count quite a large number of churches here in London, namely a few more than sixty, that is to say, those that had towers and could be distinguished from other large buildings…’ (Courtesy: Yale Center for British Art. YCBA/lido-TMS-320. Painting by Canaletto (1697-1768). Public Domain).Several of the seventeen Linnaeus Apostles visited for periods or even stayed for years in the metropolis of London. But without a doubt, Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) was the former Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) student who was most observant about how unhealthy the intense coal burning seemed to be for the inhabitants and even included lists of herbs and trees which did not tolerate the coal smoke. On 13th March 1748 in London, the inconvenience of coal smoke for linen shirts was noted among many enlightening details of health disadvantages and environmental effects. Even if it in the mid-18th century appears to have been negatively affecting the immediate geographical area only:

- ’When one lit a fire with coals, they could not be ignited directly, but one had to lay small splinters of wood or paper or a linen rag to burn underneath them as well as blowing on them slowly when they began to smoulder and catch fire. These could be used in the same way as wood for cooking food, forging iron etc.; but they had the disadvantage that their smoke quite soon blackened everything: during the winter, when many fires were lit in London, one could hardly wear a cuffed shirt longer than a day, as the cuffs were so quickly soiled by the smoke; and if one wore it for 2 days or 3, the cuffs were often as sooty as if one had helped the chimney-sweep to clean the chimney. …The houses were either black or grey from the coal smoke. For a stranger who was unused to it, this coal smoke was very troublesome, for it affected one’s chest excessively and caused a severe cough, especially at night; I experienced that personally, however free from a cough I was, when I went up to London now and then. I, too, developed one when I had been there for a day, which never failed, and as soon as I left London and had been in the country for a few days, I was rid of my cough. The same was said by everyone, even native Englishmen, who lived far out in the country and were not used to coal smoke when they occasionally had to come up to London on business.’

Overall, the environmental issue in London (the largest city in Europe with almost 750,000 inhabitants) must have troubled Pehr Kalm, according to his meticulously kept personal accounts. He had obviously not encountered air pollution to such a degree before, which was so intertwined in people's everyday lives. Even when leaving England by ship via Dover, he continued to be occupied with the effects of coal smoke – this time focusing on the ship sails woven of hemp or linen. On 8th August 1748, he noted:

- ‘The captains alleged that the coal smoke in London was quite damaging to their rigging, in that it makes it fragile and, as it were, rots it. I find it difficult to understand how that would happen, but others deny that the smoke from coal has such a bad effect.’

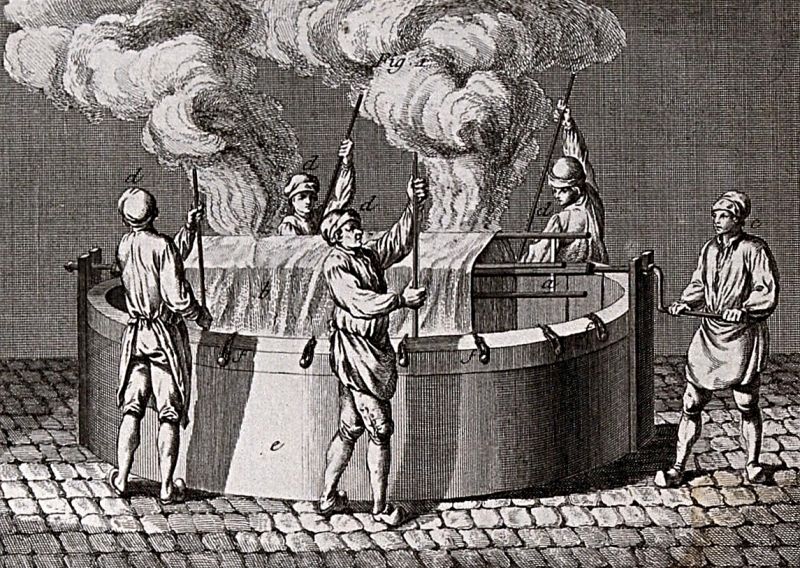

This French engraving of dyers at ‘Teinture des Gobelins’, dating to circa the 1760s, gives a good understanding of the often hazardous work of dyeing yarn and cloth. Not seldom, toxic substances were part of the process – like tin, arsenic or lead – to achieve the desired durable colours. Observations by Carl Linnaeus during his provincial tours in Sweden give further information about professional and home dyers conditions.|Engraving and print by Robert Bénard (1734-1777) and Louis-François Petit-Radel (1740–1818). (Courtesy: Wellcome Collection 44057i, part of. Public Domain).

This French engraving of dyers at ‘Teinture des Gobelins’, dating to circa the 1760s, gives a good understanding of the often hazardous work of dyeing yarn and cloth. Not seldom, toxic substances were part of the process – like tin, arsenic or lead – to achieve the desired durable colours. Observations by Carl Linnaeus during his provincial tours in Sweden give further information about professional and home dyers conditions.|Engraving and print by Robert Bénard (1734-1777) and Louis-François Petit-Radel (1740–1818). (Courtesy: Wellcome Collection 44057i, part of. Public Domain).Alum was a relatively harmless metal salt to handle, whereas many other substances used in the textile dyeing processes at the time were highly poisonous. Those included, for instance, anything from copper oxide and iron sulphate to such genuine risks to health as lead and arsenic. Not only did such toxic substances pose a direct danger for the dyers, but the yarns were also extremely sensitive to the slightest overdose of any of them. The result was often a very brittle thread, particularly the yarn dyed black after being steeped in an iron mordant. Many other less hazardous substances were also used as additives in order to reinforce and improve the colours, mainly salt, potash, urine, oak apples and quicklime, all of which Carl Linnaeus described during his provincial tours in Sweden. Many of those minerals, on a scale from moderately hazardous to highly poisonous, also appear frequently in contemporary dye-books as indispensable ingredients for textile dyeing. In most cases, however, the home dyeing was comparably less of a health hazard, using predominantly mordants such as alum, mud and urine, as chemicals were expensive to obtain.

![During Carl Linnaeus’ Västergötland journey in the summer of 1746, other mineral substances were noted to be kept at Jonas Alström’s Manufacture in Alingsås, which indicates that the dyers’ living conditions were very unhealthy. On 7th July, listed in Linnaeus’ journal, for instance: ‘vitriol (Swedish), tartar (white, red), soda, sal ammoniac, the spirit of nitre [nitric acid], arsenic, brown ochre, yellow ochre, basic cupric acetate, tin, lead and iron’. The wealthy Jonas Alström (1685-1761) ennobled Alströmer in 1751, portrayed here in the 1720s or 1730s, visualised his upper-class status as a textile manufacturer. In particular, emphasised via a large piece of indigo blue silk fabric draped over one shoulder, a three-piece suit of brown broadcloth, collarless with matching buttons and open sleeves and a neckcloth of silk or linen. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden. NMGrh 2088. Portrait by Johan Henrik Scheffel (1690-1781) Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/3a-jonas-alstrom-664x811.jpg) During Carl Linnaeus’ Västergötland journey in the summer of 1746, other mineral substances were noted to be kept at Jonas Alström’s Manufacture in Alingsås, which indicates that the dyers’ living conditions were very unhealthy. On 7th July, listed in Linnaeus’ journal, for instance: ‘vitriol (Swedish), tartar (white, red), soda, sal ammoniac, the spirit of nitre [nitric acid], arsenic, brown ochre, yellow ochre, basic cupric acetate, tin, lead and iron’. The wealthy Jonas Alström (1685-1761) ennobled Alströmer in 1751, portrayed here in the 1720s or 1730s, visualised his upper-class status as a textile manufacturer. In particular, emphasised via a large piece of indigo blue silk fabric draped over one shoulder, a three-piece suit of brown broadcloth, collarless with matching buttons and open sleeves and a neckcloth of silk or linen. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden. NMGrh 2088. Portrait by Johan Henrik Scheffel (1690-1781) Public Domain).

During Carl Linnaeus’ Västergötland journey in the summer of 1746, other mineral substances were noted to be kept at Jonas Alström’s Manufacture in Alingsås, which indicates that the dyers’ living conditions were very unhealthy. On 7th July, listed in Linnaeus’ journal, for instance: ‘vitriol (Swedish), tartar (white, red), soda, sal ammoniac, the spirit of nitre [nitric acid], arsenic, brown ochre, yellow ochre, basic cupric acetate, tin, lead and iron’. The wealthy Jonas Alström (1685-1761) ennobled Alströmer in 1751, portrayed here in the 1720s or 1730s, visualised his upper-class status as a textile manufacturer. In particular, emphasised via a large piece of indigo blue silk fabric draped over one shoulder, a three-piece suit of brown broadcloth, collarless with matching buttons and open sleeves and a neckcloth of silk or linen. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Sweden. NMGrh 2088. Portrait by Johan Henrik Scheffel (1690-1781) Public Domain).During the same Västergötland Journey in 1746, Linnaeus visited the Höjentorp estate. There was, among other things, a sizeable sheep-breeding farm, described on 26th June as: ‘The water by the dam or little lake nearest to Höjentorp was so sharp that it turned the clothes washed therein not only yellowish but also so brittle that they shortly afterwards fell apart.’ On the other hand, it was not mentioned why the water had been so polluted by toxins. It might have been the vast tobacco plantations in the area that caused the poor water quality or possibly the activities of the sheep farm, which were the polluters as chemical substances were used when washing the wool and skins. After each provincial tour in 1741, 1746 and 1749, Linnaeus spent most of his time at Uppsala. Thanks to his professorial title, he was now able to devote himself wholeheartedly to botany and continuously published his observations and conclusions, something he kept up ceaselessly during his entire life. These three tours were financed by the parliament as they were considered politically significant for ascertaining the best development potential for the country’s mercantile economy, to help the start-up of more manufacturing, for instance, which could result in improved conditions for the country as well as for its inhabitants. He also purchased a small manor house at Hammarby in the 1750s, where the family could enjoy a healthier environment in the summer, seeing as towns at that time were crowded, dirty and particularly unhealthy in the warm season.

A different branch of “textile dangers” came to be the experimental interest and anticipation to discover new functional raw materials during global encounters made by the Europeans and individuals on other continents in their network, like this uniquely fragmented preserved plaited purse of tremolite asbestos thread given by Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) to Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) in the mid-1720s. The use of asbestos has a history stretching back thousands of years. Still, on most occasions, the mineral can be traced to or was mentioned in historical documents for purposes other than textile fibres or weaving. Asbestos was likewise only noticed in travel journals by the Linnaeus Apostles a few times. Including once again Pehr Kalm, who mentioned the rare purse, given by Benjamin Franklin to Sir Hans Sloane, whilst Carl Peter Thunberg made observations in the 1770s Japan on asbestos fibres which were spun and woven into cloth. (Courtesy: The Trustees of the British Museum. Public Domain).

A different branch of “textile dangers” came to be the experimental interest and anticipation to discover new functional raw materials during global encounters made by the Europeans and individuals on other continents in their network, like this uniquely fragmented preserved plaited purse of tremolite asbestos thread given by Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) to Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) in the mid-1720s. The use of asbestos has a history stretching back thousands of years. Still, on most occasions, the mineral can be traced to or was mentioned in historical documents for purposes other than textile fibres or weaving. Asbestos was likewise only noticed in travel journals by the Linnaeus Apostles a few times. Including once again Pehr Kalm, who mentioned the rare purse, given by Benjamin Franklin to Sir Hans Sloane, whilst Carl Peter Thunberg made observations in the 1770s Japan on asbestos fibres which were spun and woven into cloth. (Courtesy: The Trustees of the British Museum. Public Domain).It may be noted that the use of asbestos – as a textile raw material – seems to have been very rare despite the desire of the period in many countries to make use of everything that could benefit the economy. However, Pehr Kalm mentioned asbestos more than once during his stay in Philadelphia between 1748 and 1750. On 11th November 1748, he included the following in his journal on the subject and the purse illustrated above from one of his discussions with Benjamin Franklin:

- ‘The mountain flax, a or that kind of stone, which Bishop Browallius calls Amiantus fibris separabilibus molliusculis, in his lectures on mineralogy, which were published in 1739, or the amiant with soft fibres which can easily be separated, is found abundantly in Pennsylvania. Some pieces are very soft, others pretty tough: Mr. Franklin told me that twenty and some odd years ago, when he made a voyage to England, he had a little purse with him, made of the mountain flax of this country, which he presented to Sir Hans Sloane.’

Pehr Kalm must have considered the item of importance due to that about a year later, on 17th November 1749, he mentioned the same purse a second time:

- ‘Mineral flax, a kind of either amianthus or asbestos, was said by almost everybody to exist in this country. Mr Franklin has had a whole pouch that was made entirely of this, which he gave to Sir Hans Sloane when he visited London…’

‘Fibrous tremolite asbestos on muscovite’ – the same type of asbestos used for the plaited purse above and as observed by the naturalist Pehr Kalm. (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London. Public Domain).

‘Fibrous tremolite asbestos on muscovite’ – the same type of asbestos used for the plaited purse above and as observed by the naturalist Pehr Kalm. (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London. Public Domain).Before his voyage to Philadelphia and the North American colonies, Kalm visited Sir Hans Sloane's extensive collection in Chelsea, London, on several occasions from the 28th of April to the 26th of May 1748. From Sloane’s famous collection – a gentleman by now in his late eighties – the young Kalm listed a large number of “curious pieces”, natural history items and books. Even if Kalm did not mention this particular purse, the object had been kept in Sloane’s care since the mid-1720s.

A later student of Carl Linnaeus made another notation about asbestos for textile use – the apostle Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) – who travelled in Europe, southernmost Africa, Southeast Asia and Southeast Asia and Japan for nine years in the 1770s. His visit to Jedo/Edo [Tokyo] on 23rd May 1776 included the following observation:

- ‘Asbestos, and immature species, called Isiwatta. Cupreous Pyrites, from Simotske and Asjo jamma, or from Asjo mountain. A copper ore, brought hither from China, was called Simoo Seki: it contained a great quantity of sulphur, and was said, when burned and reduced to powder, to be used in coughs. A white and fixed porcelain clay, of a farinaceous consistency, was called Fak Sekisi. This, together with a great variety of other minerals from the Cape, as also Bezoar and precious stones, I presented to my much-esteemed preceptor, the Chevalier Bergman, and may be seen in the collection of fossils belonging to the royal academy at Upsala; also a white Asbestos with soft and fine fibres, called Sekima, which is spun and woven, and made into cloth.’

Despite these observations and a reference to the ‘Royal Academy at Upsala” together with the preserved 18th century purse, it has not been possible to trace any more textiles from this period made of asbestos. Judging by the sparse interest in the mineral, it may be assumed that it gave little gain in proportion to the effort in the pre-industrial period, whilst many countries intended to increase the domestic economy in all ways possible. Or was there already at this time a suspicion of the health hazards with asbestos – and people, due to that, avoided too close contact with the material, particularly for clothing or other personal objects?

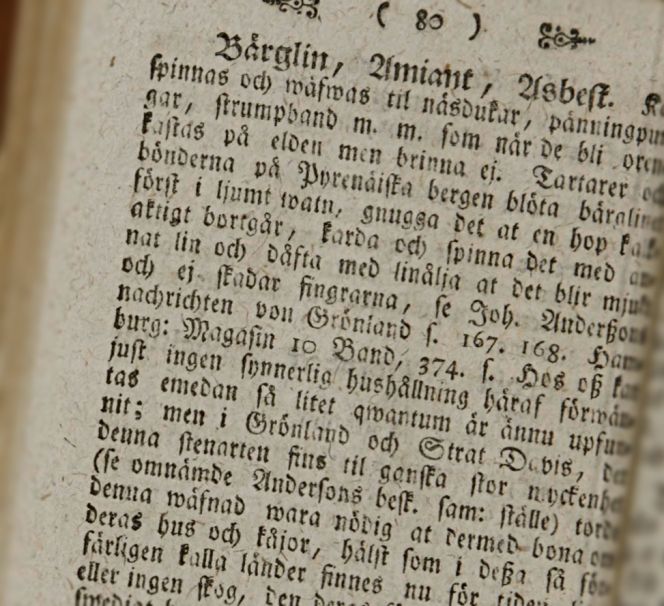

Asbestos in Lorens Wolter Rothof’s (1724-1787) Swedish household publication. (From: Rothof…1762, p. 80).

Asbestos in Lorens Wolter Rothof’s (1724-1787) Swedish household publication. (From: Rothof…1762, p. 80).Lorens Wolter Rothof was not regarded as one of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles. Still, he was among the hundreds of young students participating in his botanical excursions in Uppsala during the 1740s. From the perspective of asbestos, in 1762, Rothof published a housekeeping dictionary structured alphabetically from A-Ö. This was an extensive volume, counting 742 pages (see sources). Almost a hundred subject names were related to natural dyes, textile raw materials, a wide selection of fabrics, laundry, sail cloths, etc., including ‘Asbestos’ illustrated above. In the process of spinning, he noted in translation:

- ‘Mountain flax, Amiant, Asbestos; can be spun and woven to handkerchiefs, purses, garters etc., which, when they become dirty, may be thrown on the fire, but are burning. Tartars and farmers in the Pyrenean mountains soak the mountain flax, first in tepid water, rub it together so the lime is pressed out, card and spin it with flax and scent [sprinkle] with linseed oil, so it becomes soft and not hurting the fingers…’

In conclusion. Even if Thunberg was born almost 30 years after Kalm and 20 years after Rothof, they were all three former students of Carl Linnaeus, and he too had a connection to Sir Hans Sloane. On his homeward journey, during his time in London (Dec. 1778), Thunberg visited The British Museum, among many places, where he, from a historical point of view, studied the collections and mentioned in his journal: ‘These were now almost a hundred years old, and had been bought up by Sir Hans Sloane, after the Author’s death.’ Thunberg, Kalm, Franklin and also Linnaeus had a connection to Sloane. In his younger years in 1736, Linnaeus stayed in London and, at that time, visited Sloane’s cabinet of curiosities and natural history. It is also notable that observers during this pre-industrial period had limited interest and experience of toxic gases and environmental aspects concerning personal health, clothes etc. The seventeen Linnaeus Apostles’ travel journals, stretching over 5,500 pages, never or rarely included any such words as environmental, toxic, toxins, pollution or pollute. The air outdoors, with a few exceptions in a high-density populated city like London, was still pristine and free from human impact in most visited places on all continents in the 18th century.

Sources:

- Blundt, Wilfrid, The compleat naturalist, A life of Linnaeus, London 1971.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (See this book for more information about the 17 Linnaeus Apostles’ textile observations).

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa…åhr 1741, Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befalling… åhr 1746, Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749…, Stockholm 1751.

- Rothof, Lorens Wolter, Hushålls-Magasin, Första Delen om Hushålls-ämnen Till Deras nytta, bruk och skada, beskrivne uti Oekonomiska Föreläsningar…, Skara 1762 (quote in translation, p. 80).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Warg, Cajsa, Hjelpreda i Hushållningen för unga Fruentimber, Stockholm 1755.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE