ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

PORTRAITS AND OTHER ARTWORK

– at a Manor House in 1758

Portraits, landscape paintings, engravings, maps and other artistic decorations for walls – listed in an Inventory of Christinehof Manor House in 1758 – were exclusively placed in the countess’ and count’s suite of rooms on the grand first floor. This essay will follow the objects from room to room, assisted by correspondence between family members, which gives further insight into the slow process when sitting for the well-renowned portrait artist Gustaf Lundberg in Stockholm. Portraiture and representation of the body from this period often depicted wealthy individuals in the latest fashion, like clothes made of luxurious textile materials and comfortable banyans alike. Equally as the Swedish East India Company trade, ownership of French engravings and an interest for the local area via maps are visible in the listed objects.

Claes Ekeblad the Younger (1708-1771) circa 1750. This is one portrait among several portrayed individuals of the 18th century Piper family’s wider circle of relatives and friends, which today hang at Christinehof. However, it is unknown if Ekeblad at any point visited the manor house, but he belonged to the same generation as Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770) and Ulrika Christina Mörner of Morlanda (1709-1778) who lived at Christinehof during the warmer part of the year at the time of this written Inventory in 1758. Equally as both aristocratic families – Piper as well as Ekeblad – had one of their residences in Stockholm. Notice the original rococo gilded frame and the wealthy man’s clothing, a representative dress used by the council of the realm, consisting of costly materials as crimson red velvet, linen laces, ermine and the Order of the Seraphim chain.|Oil on canvas, probably painted by Gustaf Lundberg (1695-1786). (Collection: Christinehof manor house). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Claes Ekeblad the Younger (1708-1771) circa 1750. This is one portrait among several portrayed individuals of the 18th century Piper family’s wider circle of relatives and friends, which today hang at Christinehof. However, it is unknown if Ekeblad at any point visited the manor house, but he belonged to the same generation as Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770) and Ulrika Christina Mörner of Morlanda (1709-1778) who lived at Christinehof during the warmer part of the year at the time of this written Inventory in 1758. Equally as both aristocratic families – Piper as well as Ekeblad – had one of their residences in Stockholm. Notice the original rococo gilded frame and the wealthy man’s clothing, a representative dress used by the council of the realm, consisting of costly materials as crimson red velvet, linen laces, ermine and the Order of the Seraphim chain.|Oil on canvas, probably painted by Gustaf Lundberg (1695-1786). (Collection: Christinehof manor house). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.![Interestingly in comparison to artwork at the manor house, the 1758 Inventory listed for the Hall: ‘Two crowns of elm wood depicting the [present] king and queen with their names below, made in 1755 with green and white ‘skirdük’ covers. The top fabric sample woven around the same period, visualises how ‘skirdük’ cloth were woven in a transparent linen tabby quality or so-called cambric – here in white only. Fine linen, which was practical for occasional artwork covers to protect the valuables from sun, dust or dirt. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm…Anders Berch Collection. No. NM.0017648B:80, Digitalt Museum).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-skirduk-664x1063.jpg) Interestingly in comparison to artwork at the manor house, the 1758 Inventory listed for the Hall: ‘Two crowns of elm wood depicting the [present] king and queen with their names below, made in 1755 with green and white ‘skirdük’ covers. The top fabric sample woven around the same period, visualises how ‘skirdük’ cloth were woven in a transparent linen tabby quality or so-called cambric – here in white only. Fine linen, which was practical for occasional artwork covers to protect the valuables from sun, dust or dirt. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm…Anders Berch Collection. No. NM.0017648B:80, Digitalt Museum).

Interestingly in comparison to artwork at the manor house, the 1758 Inventory listed for the Hall: ‘Two crowns of elm wood depicting the [present] king and queen with their names below, made in 1755 with green and white ‘skirdük’ covers. The top fabric sample woven around the same period, visualises how ‘skirdük’ cloth were woven in a transparent linen tabby quality or so-called cambric – here in white only. Fine linen, which was practical for occasional artwork covers to protect the valuables from sun, dust or dirt. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm…Anders Berch Collection. No. NM.0017648B:80, Digitalt Museum).The royal theme continued in the Countess’ Drawing Room, with the earlier ‘King Carl 12th’s portrait, oblong shaped with a gilded frame’. The Piper family as part of the aristocratic elite in Sweden during the 18th century was closely intertwined with royalties, Carl XII was one of them, due to that the tenant in tail Carl Fredrik Piper’s father Carl Piper, had been this king’s most trusted minister during many years. This connection is one reason for why such a painting – even if the portrayed died 40 years prior to the Inventory in 1758 – was part of their domestic sphere. Together with that royal portraits were popular and highly admired in wealthy Swedish homes at the time. The gilded frames on such pantings, made by master furniture makers or well-renowned specialist sculptors in Stockholm, craftsmanship which was particularly concentrated to the capital where the Piper family had one of their other estates. It must also be kept in mind that within such an aristocratic family, as an owner of more than ten manor houses (from 1747 as an estate in tail, to secure that the family estates stayed together for the future), even so individual members over the generations to some extent rearranged, transported various objects between their homes as well as sold and bought properties during the 18th century. Art was no exception.

Another type of artwork was placed in the Countess’ Cabinet: ’4 Chinese paintings or paper pieces in the window’. The Piper family had several connections to China via the Swedish East India Company, of particular importance was that the present tenant in tail, Carl Fredrik Piper owned ‘six shares or lots in the East India Company’ to a value of 6,000 Rixdollar silver coins’ during the 1750s, which with every successful voyage could bring in a dividend of between 30 and 50%. This enterprise was not only lucrative financially but also gave the family access to a wide range of desired merchandise from China; artwork was one such category of objects. In the same room was equally listed: ‘9 French engravings of various sorts, with glass and fully gilded frames with multum covers’. Such woollen cloth covers, which protected the fine French engravings was a type of woollen quality – called multum or molton in 18th century Sweden: a kind of coarse twill or tabby woven fabric, in one colour or stripes, napped on one or two sides to be soft. Woollen cloths of this sort were woven by Josias Hegard’s woollen manufacturer in Malmö, circa 100 kilometres from Christinehof Manor House. One may speculate however, if these particular woollen cloths were of French origin, just as the artwork themself. Samples of such fabrics are included in the Anders Berch Collection, which originated from Rouen, Beauvais, and Languedoc and was woven circa 1740-60s, which is equally named “molton” in French. If these French engravings were imported goods purchased in a Stockholm shop, or acquired by Carl Fredrik Piper himself when staying in Paris as a young man during the 1720s is unknown. Engravings without mentioned provenance were additionally listed in the Young Lady’s Chamber as: ‘4 engravings with glass and brown frames with golden edges’.

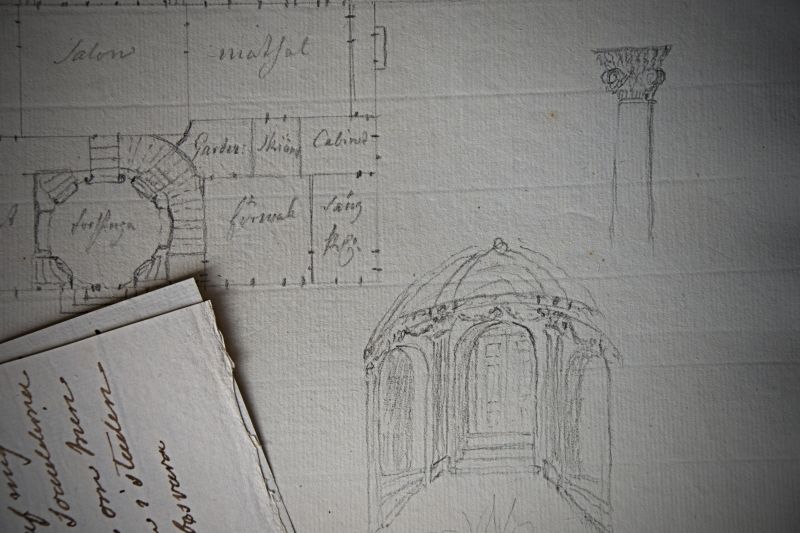

The historical archive at Christinehof manor house has a rich selection of documents giving evidence for the Piper family’s high standard of living over the years from a multitude of perspectives, including ongoing planning of interiors and exteriors of the family’s properties visualised in text and drawings. Exemplified here with undated documents – in total 25 pages of text and seven drawings – from the 1750s to 1770s and linked to the family manor house named Toppeladugård, which had been in their ownership since 1712. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no. D/III 8). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The historical archive at Christinehof manor house has a rich selection of documents giving evidence for the Piper family’s high standard of living over the years from a multitude of perspectives, including ongoing planning of interiors and exteriors of the family’s properties visualised in text and drawings. Exemplified here with undated documents – in total 25 pages of text and seven drawings – from the 1750s to 1770s and linked to the family manor house named Toppeladugård, which had been in their ownership since 1712. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no. D/III 8). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.According to the Inventory of 1758, artwork were most richly represented in the Excellency’s Drawing Room, some of these in the form of engravings:

- ‘1 engraving representing the Creation, with glass and brown varnished frame and a narrow golden edge.

- 3 engravings, depicting landscapes.

- 6 engravings, drawn with pencil of Gÿllenskepp [probably the name of the artist].’

All these engravings, except the first mentioned, were taken to Krageholm Manor House in 1764 – learned via additional notes in the Inventory, which give information about frequent transports of objects between the family’s houses. Meanwhile, the necessity for wealthy landowners to know the local geography – primarily of their own land areas – is visible via preserved maps. For instance, in a window of the same drawing room, two maps of the south Swedish provinces of Skåne and Halland. In His Excellence Bedchamber, another group of artwork were listed, with a local, Royal, as well as unknown origin.

- ‘1 painting made by the estate bailiff Hiort.

- 2 paintings with brown gilded frames and glass, with various gilded and painted animals.

- 8 paintings ditto.

- Depictions of three kings; Carl 12th, Friedrich and our now reigning King Adolph Friedrich.’

The Excellency’s Drawing Room was also the place for several portraits of family members. Among these the present count in 1758 Carl Fredrik Piper’s parents, which at these separate paintings by David Klöcker Ehrenstråhl demonstrate wealth and power via their luxurious clothing. The portraits can be traced to the years 1690-98, due to that Christina Törne (1673-1752) and Carl Piper (1647-1716) got married in 1690 and the artist died in 1698. The young lady wore a silk gown with elbow-length lace-ruffled sleeves and a banyan style garment, whilst her arm is resting on what seems to be an ermine cape with red woollen or silk lining. Her husband was portrayed in a typical elaborate wig of the time and dressed in a voluminous red silk or woollen ermine edged banyan over a silk justacorps and long-sleeved ruffled shirt with matching cravat. (Collection: Christinehof manor house). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The Excellency’s Drawing Room was also the place for several portraits of family members. Among these the present count in 1758 Carl Fredrik Piper’s parents, which at these separate paintings by David Klöcker Ehrenstråhl demonstrate wealth and power via their luxurious clothing. The portraits can be traced to the years 1690-98, due to that Christina Törne (1673-1752) and Carl Piper (1647-1716) got married in 1690 and the artist died in 1698. The young lady wore a silk gown with elbow-length lace-ruffled sleeves and a banyan style garment, whilst her arm is resting on what seems to be an ermine cape with red woollen or silk lining. Her husband was portrayed in a typical elaborate wig of the time and dressed in a voluminous red silk or woollen ermine edged banyan over a silk justacorps and long-sleeved ruffled shirt with matching cravat. (Collection: Christinehof manor house). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Other paintings listed in the same drawing room included: ‘2 portraits in gilded frames’ and in 1760 an additional note listed ‘1 large portrait in a gilded frame depicting count Magnus Fredrich Brahe’ (1756-1826) – that is to say Carl Fredrik Piper’s small grandson. Finally, in this drawing room, two portraits of the young boy’s parents, together with preserved correspondence, reveal quite an interesting story about the commission of art, emotional attachments, material culture and portraiture of the time. The description stated: ‘2 portraits of Count Brahe and Countess Christina Charlotta Piper widow of the late Count, in gilded sculptured frames’. This was Carl Fredrik Piper’s youngest daughter born in 1734, whom in 1754 married Eric Brahe who was executed for treason already two years later in 1756, therefore the remark ‘widow of the late Count’ in the Inventory of 1758. See her portrait below.

Christina Charlotta Piper (1734-1800), by the famous portrait painter Gustaf Lundberg (1695-1786), probably around the time of her marriage in 1754. She had chosen to be portrayed in a day cap of linen or cotton, a luxurious and equally warm fur lined deep-blue silk cloak, with her gown just visible. (Courtesy: Skokloster Castle, Sweden. no: SKO 3202. Digitalt Museum).

Christina Charlotta Piper (1734-1800), by the famous portrait painter Gustaf Lundberg (1695-1786), probably around the time of her marriage in 1754. She had chosen to be portrayed in a day cap of linen or cotton, a luxurious and equally warm fur lined deep-blue silk cloak, with her gown just visible. (Courtesy: Skokloster Castle, Sweden. no: SKO 3202. Digitalt Museum).The portrait of Christina Charlotta and the listed painting in the Inventory, may be compared with a letter from her brother Carl Gustaf to their father Carl Fredrik Piper in April 1759: ‘The copies of sister’s and brother in law’s portraits are finalised and I have myself seen them at Lundberg’s and found them quite the same, and as soon as the ship anchors, they shall be sent after the command. However, with the originals of my dear father and mother it does not go so quickly…’ This letter referred to copies of the portraits listed in the 1758 Inventory, also revealing that these portraits had been painted by the well-renowned Gustaf Lundberg – just like on the single portrait above. It may also be noted that Carl Gustaf had another sister, Ulrika Fredrika (1732–1791), but she was married first at the age of 39 in 1771, so she was not the sister mentioned in this letter. Lundberg had already had a long working life at this time, and since 1750, he has worked as a prestigious court portrait painter in Stockholm. Interestingly, the incredible patience needed with such portraits can be gleaned from a letter dated in 1766, more than seven years after the previous mentioning of the portraits. The son Carl Gustaf wrote to his father: ‘My dear parents’ portraits have now been packed by Lundberg and is collected’. Furthermore, the number of visits to the same artist has been traced in a letter dated August 1768 when Carl Gustaf informed his father: ‘Regarding my portrait, I have been sitting twice, so two more sittings are still missing’.

Judging by a wide selection of preserved 18th century documents in the Piper Family archive and preserved contemporary portraits, Gustaf Lundberg who lived up to the old age of 90, seemed to have been the preferred artist by the family. This may have been due to his international fame on the Continent as a rococo painter and later on as a Swedish court painter. Equally as his pure artistic skills and attention to detail of luxurious textile material as patterned silks, lacework, passementerie, fur-edged clothing etc were highly desired for portraits of men, women and children alike whom belonged to the wealthiest strata of society.

This is the fourteenth and final essay based on an Inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House. Quotes from the original documents are translated from Swedish to English.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (research visits, from the late 1980s to 2016).

- Hansen, Lars, Piper, Carl & Piper, Christina, Tankebok, Piperska Handlingar No. 4, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd sid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004 (pp. 24-25 & 38-62).

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive. 1758 Inventory: no D/Ia, Documents Toppeladugård: D/III 8, Correspondence: E/IIa 1-3 & Shares etc: F/IId 2).

- Lagerquist, Marshall, Möbelhandeln i Sverige före 1780, 1981.

- Mannerstråle, Carl-Filip, Nya huset i Andrarum Anno 1741, Piperska Handlingar No. 1, Christinehof 1991.

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, 1700-tals Textil – 18th Century Textile, Stockholm 1990 (The Anders Berch Collection: p. 108. French ‘molton’. p. 187, Linen).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE