ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

RARE FURNISHING TEXTILES, SILK RIBBONS AND CLOCKS

– at a Manor House in 1758

Sweden has a long tradition of rug making using various techniques of wool and linen, but these were originally used for warmth in beds instead of decorating and keeping the floors warm. Even if imported examples from the Ottoman Empire and other geographical areas existed, still, in the mid-18th century, floor carpets were unusual, even in aristocratic homes. This circumstance is, for instance, evident in hand-written detailed inventories but also in contemporary interior paintings, which, with few exceptions, lack such furnishing in wealthy Swedish homes. In this thorough study of a preserved 18th century inventory at a manor house – floor coverings and various objects of textile materials, a chamber-pot cupboard, clocks and contemporary letters will be in focus.

Original wooden parquet flooring in a drawing-room on the first floor at Christinehof manor house, which displays one of the star corner motifs. Already when the house was newly built in 1741, it was documented as: ‘The floor of oak, shaped and polished with three stars in the three corners, the fireplace in the fourth corner and a centred star-shape.’ (Quote from: Mannerstråle, p. 13). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Original wooden parquet flooring in a drawing-room on the first floor at Christinehof manor house, which displays one of the star corner motifs. Already when the house was newly built in 1741, it was documented as: ‘The floor of oak, shaped and polished with three stars in the three corners, the fireplace in the fourth corner and a centred star-shape.’ (Quote from: Mannerstråle, p. 13). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The Inventory dated 1758 listed three mats only, all placed in the Hall on the first floor, mentioned as ‘one large sheep mat to use under the table and two ditto mats used under the chairs in the passage’. It is uncertain if the textile furnishing referred to woollen woven carpets or sheepskins. These mats were probably used for warmth – when dining by the table or relaxing in the chairs – as the flooring was made of cut stone slabs. In several other rooms on this first floor, however, there seems not to have been any desire to include decorative carpets due to the beautifully inlaid wooden floors with geometric patterns. The Countess’ Bed-Chamber listed as a ‘parquet floor of pine with six angular squares and an inlaid black border’, whilst in the Count’s Small Hall ‘, the parquet flooring of oak was worked with a black and white inlaid border and a centred star-shape’. It may be noted that all floors on the ground and on the second level of the house were undecorated and made of plain pine boards or cut stone slabs.

Even later interior paintings from aristocratic Swedish homes, by the artist Pehr Hilleström circa 1770s-1790s, give several examples of complex inlayed wooden floors without carpets. Not only in depictions like this “The Wool Winder” when the handiwork may have stained the carpet, but also in most other wealthy interior paintings depicting everyday life 20, 30 or even 40 years after the Inventory of 1758 – which often lacked any form of mats. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Sweden. NM 2453. Wikimedia Commons).

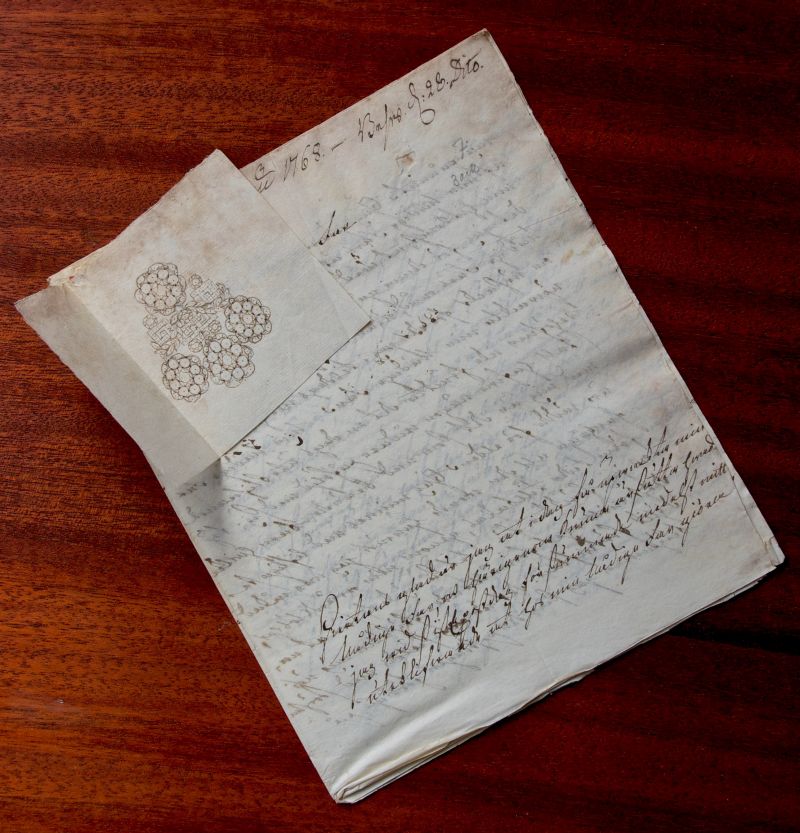

Even later interior paintings from aristocratic Swedish homes, by the artist Pehr Hilleström circa 1770s-1790s, give several examples of complex inlayed wooden floors without carpets. Not only in depictions like this “The Wool Winder” when the handiwork may have stained the carpet, but also in most other wealthy interior paintings depicting everyday life 20, 30 or even 40 years after the Inventory of 1758 – which often lacked any form of mats. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Sweden. NM 2453. Wikimedia Commons). This letter to Carl Fredrik Piper from his son Carl Gustaf Piper in 1768 is of material culture interest too, via the small drawing of a piece of jewellery attached to the letter, also mentioned in the text. Similarly to this particular letter between family members – references to fashion details, embroidery, upholstered furniture, curtains etc – have given further traces to textile related objects in the possession of this wealthy family. The majority of such correspondence was written in Swedish, but French writing was not uncommon in the wider family circle. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. E/IIa 3). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This letter to Carl Fredrik Piper from his son Carl Gustaf Piper in 1768 is of material culture interest too, via the small drawing of a piece of jewellery attached to the letter, also mentioned in the text. Similarly to this particular letter between family members – references to fashion details, embroidery, upholstered furniture, curtains etc – have given further traces to textile related objects in the possession of this wealthy family. The majority of such correspondence was written in Swedish, but French writing was not uncommon in the wider family circle. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. E/IIa 3). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.More than three hundred letters written between 1758 and 1770 are preserved from the son Carl Gustaf Piper to the father Carl Fredrik, which discussed family matters, purchases of cloth and furniture etc. In one letter dated in December 1762, he included some detailed information about measuring of time: ‘The new pendulum clock which is ordered from Sundberg will according to my dear father’s wishes be made with silver-plated fittings, but will not be ready until Christmas’. This may be the same clock which was recorded in the 1758 Inventory, via an added notation written in 1768, as a pendular clock with gilded fittings in the Countess’ Drawing Room on the first floor. An object that had been transported from Krageholm, where it originally came from Stockholm. ’ The mentioned ‘Sundberg’ in the letter, was Erik Sundberg who was a well-known master watchmaker in the capital, with his workshop at the well-reputed furniture maker Diedrich Tellerstedt’s premises at Urvädersgränd in Gamla Stan [the Old Town, today this lane is named Stenbastugränd]. Furthermore, Sundberg had been trained in Paris as a young man during the early 1740s.

The Inventory listed a second clock, placed in the adjoining Hall on the same floor, an object which also has left some historical traces: ’1 [wall] pendular clock, made by Modewig in Malmö with an elm wood case’. About one hundred kilometres from Christinehof manor house, Johan Carl Modewig lived and worked at Östergatan no. 29 in Malmö – along one of the busiest merchant streets – during the period from 1741 to 1772. It has to be assumed that someone in the Piper family, visited his shop to buy the clock prior to year 1758, when the inventory list was written or ordered the same and had it delivered. That is to say, the family, guests, and servants alike at the manor house could see the exact time by using clocks placed in two prominent rooms. Additionally, it must be assumed that the aristocratic men of the home owned a pocket watch that was kept in a waistcoat pocket. Whilst a lady could wear a watch visibly hanging in a chain, such luxury objects were part of everyone’s personal belongings and, due to this, were not included in a household inventory.

For most preserved physical objects or listed furnishing in inventory lists etc however, there are seldom such detailed knowledge about the men or women who once crafted these objects – like for the pendular clocks discussed above. For instance, braids and ribbons had many uses in the home interior as well as for clothing accessories, or as on this illustration of a bill of sale for properties from 1752-1772: including parchment, blue and yellow silk ribbons with seals attached to wooden/metal discs. Weaving of silk ribbons were quite extensive in Sweden during this period, so it is probable that ribbons for such important documents were of Swedish manufacture to support the development of the country’s mercantile economy. Or alternatively of Chinese origin, imported via the Swedish East India Company trade, but the true origins of the ribbons stay unknown. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. F/I 2, 4). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

For most preserved physical objects or listed furnishing in inventory lists etc however, there are seldom such detailed knowledge about the men or women who once crafted these objects – like for the pendular clocks discussed above. For instance, braids and ribbons had many uses in the home interior as well as for clothing accessories, or as on this illustration of a bill of sale for properties from 1752-1772: including parchment, blue and yellow silk ribbons with seals attached to wooden/metal discs. Weaving of silk ribbons were quite extensive in Sweden during this period, so it is probable that ribbons for such important documents were of Swedish manufacture to support the development of the country’s mercantile economy. Or alternatively of Chinese origin, imported via the Swedish East India Company trade, but the true origins of the ribbons stay unknown. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. F/I 2, 4). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.A few other single objects which included textile material, will give a glimpse into the relatively few such articles listed in a mid-18th century Inventory. On the second floor in the Drawing-room to the Yellow Chamber an object was placed suited for resting the feet. This piece of furniture was recorded as ’one cloth-covered feet stand, which was taken down from Stockholm in 1757’, from the Piper family’s residence “The Palace” in the capital.

On the first and second floors alike, a ‘Privy’ was listed, and both spaces were assisted by a ‘lock, key, and clasps’. Judging by the locked doors, it must be assumed that the family and their guests solely used these toilets, whilst the servants had to use privies outside the main building. Other possibilities for the family and their wider circle of visitors who stayed overnight were the chamber pots, sometimes placed in specially adapted cupboards.

![In concluding words, privies and chamber-pots were not often associated with textile materials for practical reasons, but one exception was listed in Count Adolf’s [added: Carl Gustaf’s] Chamber on the first floor. The second post reading in translation: ’One chamber-pot cupboard of blue woollen plush with edgings of imitated gold braids and lining underneath’. | Part of page from the document ‘Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758’. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family archive, no D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5-inventory-1758-800x449.jpg) In concluding words, privies and chamber-pots were not often associated with textile materials for practical reasons, but one exception was listed in Count Adolf’s [added: Carl Gustaf’s] Chamber on the first floor. The second post reading in translation: ’One chamber-pot cupboard of blue woollen plush with edgings of imitated gold braids and lining underneath’. | Part of page from the document ‘Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758’. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family archive, no D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

In concluding words, privies and chamber-pots were not often associated with textile materials for practical reasons, but one exception was listed in Count Adolf’s [added: Carl Gustaf’s] Chamber on the first floor. The second post reading in translation: ’One chamber-pot cupboard of blue woollen plush with edgings of imitated gold braids and lining underneath’. | Part of page from the document ‘Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758’. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family archive, no D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.This is the thirteenth essay based on an Inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House. Quotes from the original documents are translated from Swedish to English.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (research visits, from the late 1980s to 2016).

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004 (pp. 17-18, 25-26 & 38-62).

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive. Inventory 1758: no D/Ia, Letters: E/IIa 1-3 & Ribbons with seals: F/I 2, 4).

- Lagerquist, Marshall, Möbelhandeln i Sverige före 1780, 1981.

- Mannerstråle, Carl-Filip, Nya huset i Andrarum Anno 1741, Piperska Handlingar No. 1, Christinehof 1991.

- Malmö County Archive, Sweden (Estate Inventory: Johan Carl Modewig).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE