ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

READING, GAMES AND FASHION

– In an 18th Century Swedish Aristocratic Family

Together with music in all its forms, various leisure activities may be gleaned from preserved manuscripts and artworks of the Swedish aristocracy during the 18th century. Illustrated gamble tables by the famous genre painter Pehr Hilleström is one type of detailed source, which not only gives us information about the tables themselves but, for instance, if children took part in games, how many individuals were involved, the overall interior of the room as well as how women and men were dressed in such everyday situations. This essay aims to look more closely at indoor as well as outdoor games and the importance of reading books for all ages, assisted by a selection of contemporary objects and illustrations. The Piper Family archive keeps quite a wide range of primary sources linked to these activities. The follow-up essay on this theme – will focus on music, musical instruments and dance once taking place within this particular family.

‘Boy building card houses’ in the 1780s or 1790s, when he probably was supposed to read judging by his watchful gaze and then turned upside-down book. This unidentified wealthy boy was dressed in a brown broadcloth or a silk frock coat, a half-unbuttoned whitish-coloured waistcoat, a white shirt and a matching neckcloth. | Oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816). (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. No: NM.0252035. DigitaltMuseum).

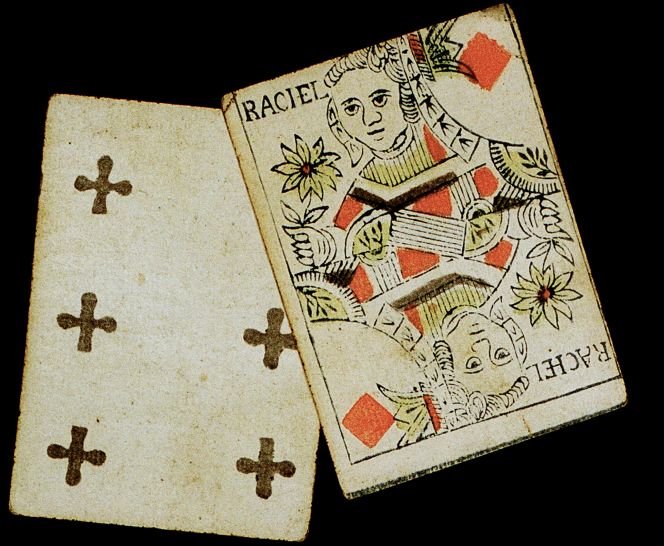

‘Boy building card houses’ in the 1780s or 1790s, when he probably was supposed to read judging by his watchful gaze and then turned upside-down book. This unidentified wealthy boy was dressed in a brown broadcloth or a silk frock coat, a half-unbuttoned whitish-coloured waistcoat, a white shirt and a matching neckcloth. | Oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816). (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. No: NM.0252035. DigitaltMuseum). Interestingly, the Piper Family archive includes two playing cards of a similar type as on the painting above, probably dating from the 1750s to 1770s, of which one is the Queen of Diamonds and the other six of clubs. The latter is entirely hand-painted, whilst the contour of the Queen is printed and finished off with yellow and red colours by hand. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX: Playing cards). Photo: The IK Foundation.

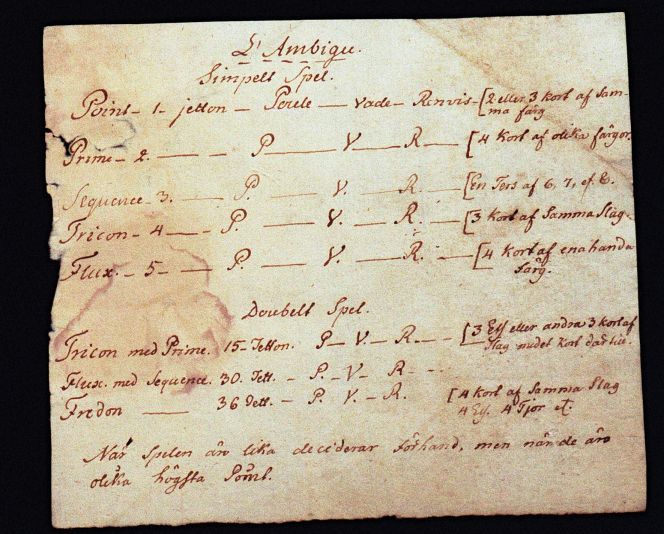

Interestingly, the Piper Family archive includes two playing cards of a similar type as on the painting above, probably dating from the 1750s to 1770s, of which one is the Queen of Diamonds and the other six of clubs. The latter is entirely hand-painted, whilst the contour of the Queen is printed and finished off with yellow and red colours by hand. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX: Playing cards). Photo: The IK Foundation. Two of the card games played within the Piper family are known due to this unique handwritten document, named Simpelt Spel (Simple Game) and Doubelt Spel (Double Game), where cards were combined with counters to keep track of the winners. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX). Photo: The IK Foundation.

Two of the card games played within the Piper family are known due to this unique handwritten document, named Simpelt Spel (Simple Game) and Doubelt Spel (Double Game), where cards were combined with counters to keep track of the winners. (Collection: Historical Archive… D/IX). Photo: The IK Foundation.The games illustrated above seem similar, with the difference that more counters were needed for the double play. It was possible to gain points if it had:

- ‘2 or 3 cards of the same colour

- 4 cards of different colours

- A tierce of 6, 7 or 8

- 3 cards of the same sort

- 4 cards of the same colour

- 3 aces or 3 other cards of the same sort

- 4 cards of the same sort.’

Furthermore, such game counters were also listed in a 1790s Inventory from the manor house Krageholm as ‘one purse with wooden counters.’

This tinted drawing of a man playing cards in Bellinga manor house, located close to the harbour town of Ystad in southernmost Sweden, is an informative depiction of leisure activity in an aristocratic home during the 1760s. The profile-styled drawing shows not only the portrayed’s concentration on the card game with his slightly bent back, but also many details of his garments typical of the period. The wig was drawn back and tied with a silk ribbon, the collarless coat of broadcloth or silk had deep cuffs fastened with buttons, and breeches were probably made of the same fabric as the waistcoat – not visible in the picture. The wide ruffled shirt cuffs, the finest silk stockings and low-heeled buckled shoes are clearly displayed. Furthermore, the Piper family was not the owner of this particular manor house, but was the owner of the neighbouring estate Krageholm, situated at a short distance of circa 5 kilometres. (Private ownership. Drawing by Jean Eric Rehn).

This tinted drawing of a man playing cards in Bellinga manor house, located close to the harbour town of Ystad in southernmost Sweden, is an informative depiction of leisure activity in an aristocratic home during the 1760s. The profile-styled drawing shows not only the portrayed’s concentration on the card game with his slightly bent back, but also many details of his garments typical of the period. The wig was drawn back and tied with a silk ribbon, the collarless coat of broadcloth or silk had deep cuffs fastened with buttons, and breeches were probably made of the same fabric as the waistcoat – not visible in the picture. The wide ruffled shirt cuffs, the finest silk stockings and low-heeled buckled shoes are clearly displayed. Furthermore, the Piper family was not the owner of this particular manor house, but was the owner of the neighbouring estate Krageholm, situated at a short distance of circa 5 kilometres. (Private ownership. Drawing by Jean Eric Rehn).Inventories, written for several of the Piper family’s manor houses, dating from the period 1750 to 1800, also give enlightening information about games and tables used for a wide range of amusement. Including descriptions like:

- Game table to fold in the middle

- Backgammon tables

- Backgammon tables without counters

- Table of inlaid work with backgammon

- Backgammon with its counters

- Dices

- New skittle game with its balls

One of these family manor houses was Ängsö, situated about 100 kilometres from the capital, Stockholm, where a unique insight into one such leisure activity can be observed from the image below.

Outdoor skittle game with balls in the garden of Ängsö manor house during one summer of the 1780s. Quite a lot is going on! Visible in the picture is the imposing four-story building. As a focal point, four gentlemen dressed in ordinary upper-class fashion and additional black hats – maybe as protection from the sun. The same goes for the two small boys, slightly beside the ongoing game. Furthermore, a servant carrying a tray heads towards some high tables and chairs with refreshments. This particular manor house had been in the ownership of the Piper family since the year 1710. (Private ownership. Black and white representation of a watercolour by Isak Kjölström).

Outdoor skittle game with balls in the garden of Ängsö manor house during one summer of the 1780s. Quite a lot is going on! Visible in the picture is the imposing four-story building. As a focal point, four gentlemen dressed in ordinary upper-class fashion and additional black hats – maybe as protection from the sun. The same goes for the two small boys, slightly beside the ongoing game. Furthermore, a servant carrying a tray heads towards some high tables and chairs with refreshments. This particular manor house had been in the ownership of the Piper family since the year 1710. (Private ownership. Black and white representation of a watercolour by Isak Kjölström).A different type of game was lotteries with money prizes, evident via the monthly Swedish newspaper Inrikes Tidningar kept in the Piper family archive. For instance, on Tuesday, 16 April 1793, it was the 332nd draw of Kongl. Swenska Nummer Lotteriet (the Royal Swedish Number Lottery), meaning that the lottery had been introduced already during the 1760s.

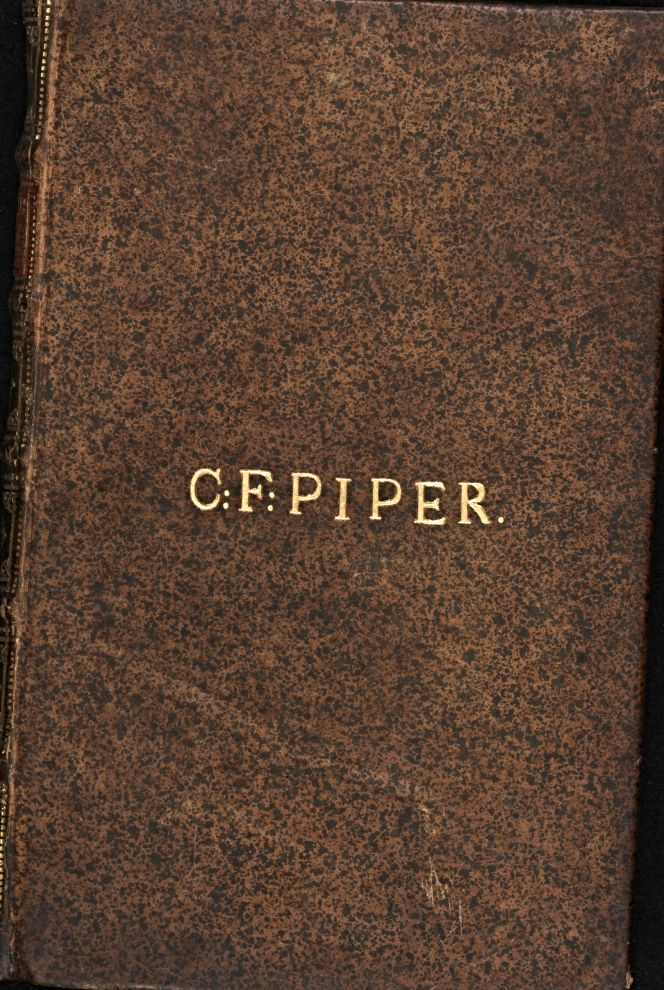

Reading books was another popular pastime and educational tool and part of religious worship, business matters or due to one’s interest to learn more about the world from a local or global perspective in various subjects. Swedish and French were the main languages for the aristocracy in Sweden, with added knowledge in Latin, German, Italian or English for some individuals. In particular for men who had studied abroad when young or made several years-long Grand Tour. On the other hand, books were regarded as personal possessions and were therefore not listed in Inventories of objects kept in the family manor houses. This book, for instance, belonged to Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770), evident via his initials and surname printed in gold on the leather-bound book cover. The French book ‘Avantures de la Comtesse de Strasbourg, et de sa fille…’ was printed in Amsterdam in 1718, so he may have had this volume among his personal belongings since his younger years or purchased it at a later date. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:194412. Public Domain).

Reading books was another popular pastime and educational tool and part of religious worship, business matters or due to one’s interest to learn more about the world from a local or global perspective in various subjects. Swedish and French were the main languages for the aristocracy in Sweden, with added knowledge in Latin, German, Italian or English for some individuals. In particular for men who had studied abroad when young or made several years-long Grand Tour. On the other hand, books were regarded as personal possessions and were therefore not listed in Inventories of objects kept in the family manor houses. This book, for instance, belonged to Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770), evident via his initials and surname printed in gold on the leather-bound book cover. The French book ‘Avantures de la Comtesse de Strasbourg, et de sa fille…’ was printed in Amsterdam in 1718, so he may have had this volume among his personal belongings since his younger years or purchased it at a later date. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:194412. Public Domain).It seems to have been relatively common in 18th century Sweden to be portrayed as reading a book, admiring a depicted book, or just having a book included in the picture for the sake of social status, educational or emotional reasons, as an accessory or other purpose. Judging by a study of a large selection of portraits over the years, men, women and children appear in this type of single or group picture. An in-depth study of the documents in the Piper family archive reveals more details about the reading and writing traditions of a private nature. Via handwritten poems of homely character – by unknown writers – poems printed in newspapers and shorter texts or ballads by well-known cultural personalities of the period. Carl Michael Bellman (1740-1795), the Swedish musician, songwriter, composer, and poet can, for instance, be linked to a document in the archive via his famous Fredmans Epistle no 34, which is regarded to have been written in August 1771. Like the printed version, this handwritten copy (with some variation of the wording) has eleven verses. Interestingly, like Bellman, the almost contemporary Carl Gustaf Piper (1737-1803) lived and worked in Stockholm for many years, more precisely between 1755 and 1788, as an upper chamberlain at the Royal Palace. Judging by extant correspondence – hundreds of letters from Carl Gustaf to his father, Carl Fredrik, dating 1758 to 1770 – he had a genuine interest in art, poems, music, literature and theatre. It is likely that Carl Gustaf was the direct link for many ongoing cultural events in Stockholm during this period. Whilst his father, Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770), corresponded with the envoy, minister etc., Carl Rudenschiöld (1698-1783), who also wrote poems of which a few have been preserved in the Piper Family archive. These short texts are conversation pieces and poems describing heroic soldiers, Crown Prince Gustaf, King Adolf Fredrik, Queen Lovisa Ulrika, et al., dating these writings from 1751 to 1771.

Additionally, Rudenschiöld was interested in music and became one of the founders of the Musical Academy in Stockholm in 1771, among many other matters during a long life. Evident via several connections to Pipers, including preserved unique handwritten poems and long-term correspondence, his wife Christina Sofia Bielke (1727-1803) was the daughter of Countess Charlotta Christina Piper (1693-1727), that is to say, sister to Carl Fredrik Piper (the correspondent) and to be assumed they had face to face meetings and gatherings in Stockholm where they stayed over long periods. Overall, Rudenschiöld seems to have been an appreciated cultural personality and diplomat in general of the time and had, via his marriage in 1756, even become one among many within the broader circle of the aristocratic Piper family itself.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor house, Sweden (research visits in the 1990s and 2016).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘På Bellmans tid – Nöjesliv och underhållning under 1700-talets andra hälft i adelskretsar på Österlen’, Österlen 1998, pp. 61-68.

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, (Piper Family Archive, no D/I & D/Ia: Inventories, Piper Family manor houses. D/IX: Playing cards, games, poems & other short texts. E/II a 1-3 correspondence. L/VI 1 Newspapers).

- Selling, Gösta, Svenska Herrgårdshem under 1700-talet, Stockholm 1937.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE