ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

RIBBONS, BANDS AND CORDS

– Observations by 18th Century Naturalists and Artists

Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) three provincial tours in Sweden during the 1740s were financed by the parliament as they were considered politically significant for ascertaining the best development potential for the domestic mercantile economy, to help the start-up of more manufacturing, for instance, which could result in improved conditions for the country as well as for its inhabitants. All sorts of ribbons, bands and cords with practical as well as decorative and fashionable purposes were regarded as essential to produce domestically – via handicrafts, manufacturing and to a small extent as possible by import. This essay will look closer into the famous naturalist’s travel journals from the perspective of ribbons and how this small object had multiple functions for clothes. Assisted by a contemporary dictionary, preserved woven ribbons and a selection of artworks, all in detail, demonstrate how ribbons formed an essential part of clothes for everyday life and festivities alike in local communities.

This oil on canvas, dated 1780, by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) shows farmers in Småland province using ribbons in traditional ways. Visibly, the young woman’s hair is arranged with decorative multicoloured bands, and both women’s aprons are held in place with ribbons while the man’s stockings are fastened with red ribbons. Wool, silk or linen were possible materials. (Courtesy: Uppsala Auktionsverk, Sweden. Wikimedia Commons. Unknown present owner).

This oil on canvas, dated 1780, by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) shows farmers in Småland province using ribbons in traditional ways. Visibly, the young woman’s hair is arranged with decorative multicoloured bands, and both women’s aprons are held in place with ribbons while the man’s stockings are fastened with red ribbons. Wool, silk or linen were possible materials. (Courtesy: Uppsala Auktionsverk, Sweden. Wikimedia Commons. Unknown present owner).Ribbons of various qualities were one of many essential textile commodities, either woven or plaited at home or sold via the pedlars. This branch of trade can also be compared with Carl Linnaeus’ travel journals, wherein he mentioned the itinerant pedlars of the Västergötland province. On 7 July 1746, he wrote: ‘The silk ribbon mill: 9 looms were in full action here, all of them weaving their ribbons, some of which were decorated with roses, some with letters, and some with other ornamentations.’ He also mentioned that ‘here 60 ribbons were woven in one week, every 50 ells in length’. They were clearly ribbons with woven designs, which could be used for clothes or furnishings.

Already during the Dalarna Journey in 1734, however, Linnaeus made a rich selection of observations linked to material culture and craft skills and even noted details like ribbons used in the traditional clothing in several parishes in this rural province of Sweden. From the town of Falun, Linnaeus set out on his journey on 3 July 1734. His company consisted of seven men with varying expertise and local knowledge in order for the eight men to find out as much as possible about botany, zoology, geology, customs and habits, way of dress etc. In the parish of Mora, on 8 July, Linnaeus made a lengthy costume description of the appearance of the garments. It was principally the women’s dress which was noted, while the men’s clothes were noted but briefly. Both jacket, or bodice, and apron were predominantly green, which was unusual in neighbouring parishes. The flaps of the bodice were divided into four parts and joined with narrow green ribbons. The neck-bands of linen had an upstanding collar, while what the observer referred to as a ‘neck-rag’, a kind of neckerchief, which commonly went under the name of ‘square-cloth’ in and around Mora. That cloth was described as being ‘fastened under the chin with a large brass pin which has to hang from its head some rhomboidal brass leaves.’ The skirt was made up after an older cut, that is to say, in the shape of a chemise or frock with shoulder straps. Around the waist was a leather belt tied to which the women attached needle-case, keys and a knife in its sheath. The stockings were made of red felted broadcloth while the apron was as long as the skirt, from which hung beautifully woven apron ribbons and bobbin lace.

Although this oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström shows a home in the parish of Mora from around 50 years after Linnaeus’ visit, not much had changed. Mora was part of a region that preserved a very antiquated form of dress for a long time and, especially the dress for going to church. That reinforces further the likelihood that the way the women were dressed during Linnaeus’ visit in 1734 would have strongly resembled the costume details depicted in this painting (even if the colour green is less dominant than in his writing), as well as for preserved garments in the Nordic Museum and other Swedish collections, dating back mainly to the 19th century. The state of dress could, in other words, be preserved in remote places, where people adhered strictly to tradition and, at the same time, were but little influenced by new trends. Notice the various uses of ribbons in the picture; for the men, their stockings were held in place with red knee bands and the woman’s leather belt tied with an attached needle case, also described by Linnaeus, is visible together with a decorative red ribbon on the ‘square-cloth’. (Courtesy: Hallwylska Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic source).

Although this oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström shows a home in the parish of Mora from around 50 years after Linnaeus’ visit, not much had changed. Mora was part of a region that preserved a very antiquated form of dress for a long time and, especially the dress for going to church. That reinforces further the likelihood that the way the women were dressed during Linnaeus’ visit in 1734 would have strongly resembled the costume details depicted in this painting (even if the colour green is less dominant than in his writing), as well as for preserved garments in the Nordic Museum and other Swedish collections, dating back mainly to the 19th century. The state of dress could, in other words, be preserved in remote places, where people adhered strictly to tradition and, at the same time, were but little influenced by new trends. Notice the various uses of ribbons in the picture; for the men, their stockings were held in place with red knee bands and the woman’s leather belt tied with an attached needle case, also described by Linnaeus, is visible together with a decorative red ribbon on the ‘square-cloth’. (Courtesy: Hallwylska Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. Electronic source).Further on, during the Dalarna Journey, in the next month, on 5 August, between Lima and Malung, Linnaeus noted that the women wore a black woollen skirt while the bodice was ‘of coloured cloth’ and they had tied a ‘border or ribbon from [woven in] Dalarna around the waist’. A week later – 11 August – an area named Nås Finnmark was traversed on the border of the province of Värmland, where the young women were seen with their hair attractively plaited while the married women wore head-cloths. Skirts and bodices were sewn together after the age-old fashion, which also appears to have been most favoured in that distant rural region. The back parts of the bodices were decorated with ribbons sewn on, and underneath, a linen chemise was worn.

In the 1740s, Linnaeus carried out a further three provincial tours: in 1741 to the islands of Öland and Gotland, in 1746 to the province of Västergötland, and in 1749 to the province of Skåne. Thanks to his professorial title, he was now able to devote himself wholeheartedly to botany and continuously published his observations and conclusions, something he kept up ceaselessly during his entire life. Practical and decorative ribbons in clothing were part of his attention, which was included in the travel journals, just as a multitude of other everyday and festive events which he happened to come across. At random at times, but on other occasions after careful planning and registration of each and every object, he noticed.

On 15 May 1741, Linnaeus travelled from Stockholm – on the Öland and Gotland journey – accompanied by six young men, two of them as young as 14 and 16 years of age. They passed through the provinces of Södermanland, Östergötland and Småland before reaching the first stop on the journey, the island of Öland on 1 June. A few days later, they were given a lesson in how best to keep moths and other damaging insects at bay with the help of aromatic herbs, and the journey continued to Alvaret in the south of the island, where Linnaeus noticed the young women’s dress. On that summer’s day, they wore a chemise, the upper part of which showed, but the lower part was covered by a thin skirt; the hair was finely plaited with ribbons. He also noted that the Öland women were diligent knitters of woollen stockings, but there was also proof of more refined knitting. That was, for instance, noticed at Högsby on 14 June among the church-going people dressed in their Sunday bests. Some women wore a neck-cloth which was ‘knitted with silk edges.’ Other details of the dress were: On the head was worn a white festive cloth of linen which was tied at the nape; in order to get the cloth properly smooth, a glass rod was rubbed against the fabric. The bodice with shoulder straps was attached to the skirt, and a wide ribbon was tied around the waist. After the company had visited both islands, Linnaeus made a lengthy dress description from the southernmost part of Småland province, dated 10 August. The men were recorded as wearing long black jackets of wadmal, decorated with a brown edging of broadcloth at every seam; the linen shirt, edged with lace, was worn on top of the wadmal jacket, while embroidered cuffs peeped out from under the jacket at the wrist. The married women wore a shiny linen cloth tied at the back of the head, and ‘the maids went about, their hair plaited with glittering ribbons and borders on festive days without their heads covered’.

Farmer’s wife and daughter in Skåne province, Herrestad district in 1807. | Watercolour by Johan Abraham Aleander (1766-1853). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 81099. Public Domain).

Farmer’s wife and daughter in Skåne province, Herrestad district in 1807. | Watercolour by Johan Abraham Aleander (1766-1853). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 81099. Public Domain).A relatively isolated area where the traditional clothing of the farming community had been preserved over many decades, making this watercolour an interesting comparison with Carl Linnaeus’ observations in 1749. Ribbons and bands are also clearly illustrated for several uses in their festive dress. On the Skåne Journey in 1749, the emphasis on the folk costume was more detailed than on previous journeys. Those observations consisted of some very comprehensive descriptions of the peasant dress and a number of shorter notes portraying the traditional use or some unique details of the costume from different areas – including ribbons of various materials. The Skåne Journey was to be Linnaeus’ last provincial journey. His objective there was to undertake as profitable a journey as possible in the service of science and later to describe his findings regarding the discoveries from nature and private œconomy. Traditions of dress, the manner of dressing for feast-days and every day and the textile materials involved formed one of many important subjects.

Linnaeus set out on his journey from Uppsala on 24 April, accompanied by Olof Söderberg, while Erik Gustav Oxenstierna and Lars Aretin were occasional companions in Skåne. Early on, before reaching his main destination – the province of Skåne – Linnaeus demonstrated a keen interest in clothes from his native area in southernmost Småland. The most detailed study of the various components of the costume originating from Virestad, dated Sunday, 14 May. Some observations connected to ribbons will be discussed in this context, including that the unmarried young women went bare-headed with various ribbons of red cloth, ‘golden cloth ribbons, black velvet borders and silver glitter ribbons’, plaited and tied into the hair. The married women wore a small basin-shaped knitted garment of white wool, which was wound around the gathered hair at the nape. On top of that, tied at the back of the head, a white linen head-square, which had been well rubbed to make it smooth and shiny. While the bodice was usually made of a kind of flowery wool fabric, shag, decorated with shiny silver ribbons along seams and on the back, in addition to which six pairs of silver loops were sewn on the front. The skirt itself was, as a rule, made of fine blue broadcloth and, wound twice around the waist and tied on the left side, a wide red sash edged with blue ribbons, the ends of which were trimmed with black silk fringes. A narrow apron of blue wool decorated with borders and shiny silver ribbons at the bottom added further splendour to the costume.

Four days later, the group arrived at Sinclairsholm in northern Skåne, where, yet again, a long description was written of the festive costume. With a particular focus on ribbons, braids and all sorts of similar accessories, he noted the following for men’s clothing. Their leather breeches were tied below the knee with multi-coloured ribbons with tassels at the ends. To complete the elegance knee-high boots with red heels were worn, as well as a black hat with a red ribbon, blue knitted finger gloves and a whip with a leather-covered handle. The women were equally well dressed, and, just as before, the headgear revealed their civil status. The unmarried women used silk ribbons and velvet braids to adorn their hair, while the married women wore the white head-cloth, typical of the province of Skåne. It was made of lightly starched linen of different sections, ingeniously constructed into a complicated headgear, the design differing from one jurisdictional district to the next. The jacket was of black broadcloth sewn with ribbons. Moreover, five pairs of small silver loops with bowl-shaped leaves were placed as decoration on a base of red broadcloth on the front of the jacket, which nonetheless was fastened with simple little hooks. The elaborately worked sleeves of the jacket had small upturned cuffs at the wrist. The green broadcloth skirt reaching the shoes was sewn onto the bodice of green velvet. That velvet was, as a rule, a rose design with decorative shiny silver ribbons, and that garment was also adorned with silver loops. The blue apron was edged with red and silver-coloured ribbons, while a wide red sash was tied around the waist. The hanging sash parts were further decorated with shiny ribbons and black fringes.

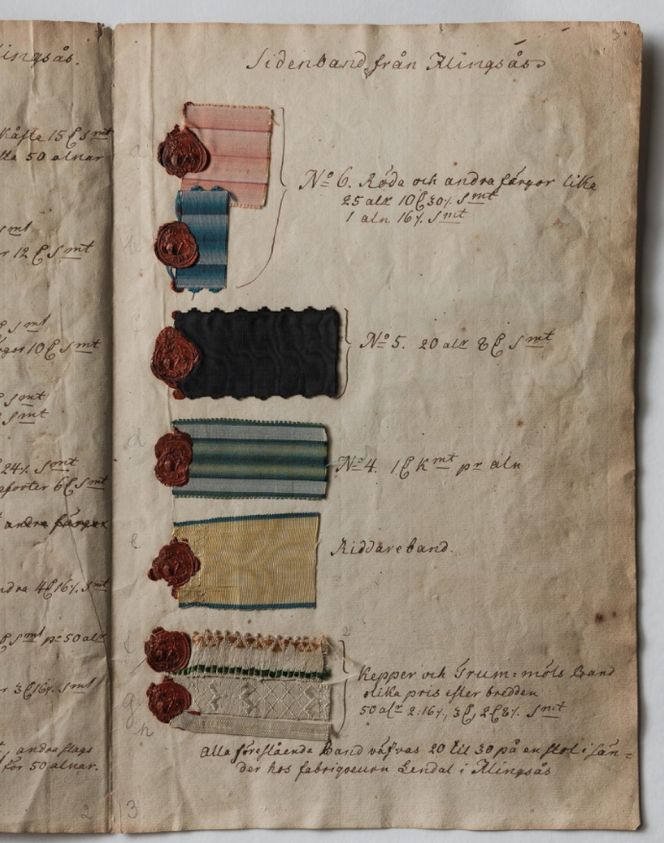

‘Silk ribbons from Alingsås’. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:20. p. 3. Digitalt Museum).

‘Silk ribbons from Alingsås’. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:20. p. 3. Digitalt Museum).Carl Linnaeus visited Alingsås during his Västergötland journey in the summer of 1746, but mid-18th century ribbon weaving from this manufacturing town cannot only be studied via his written observations, owing to that the Anders Berch Collection includes a selection of such textile samples. This preserved sample page is the third of four showing ‘Silk ribbons from Alingsås’. A material presented in the book ‘1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet’, edited by Elisabet Stavenow-Hidemark. The text on the original document, which explained these seven silk ribbons – named a-g – also registered in a translation that: ‘All the above ribbons are woven from 20 to 30 at a time on one loom by Manufacturer Lendal at Alingsås’. The four-page document had also been dated on the final page – ‘Alingsås, 25th January in 1755, Lorens Wolter Rothof’ (1724-c.1780). Rothof was an author and involved in the sheep-breeding training school in the same town. Whilst Sven Lendahl (1712-1788) was a master and manufacturer in the local silk mill, which had been active since at least 1737. According to research by the Nordic Museum, ‘In 1753 the mill had fourteen ribbon-looms of two kinds, and 60 workers’.

The second example of a sample page from the Anders Berch Collection shows: ’Samples of Padua ribbons manufactured 1758 in Stockholm’. At this time, Stockholm had six silk ribbon mills, which according to research by the Nordic Museum, ‘… had a total of altogether 58 looms and 150 workers’. Padua ribbons were woven of coarse silk, resulting in rough, non-slippery ribbons, often used in clothing and particularly popular for tying two ribbons into a bow. The three sets of ribbons in three widths have been preserved together with original 18th century explanations of each sort. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:19A. Digitalt Museum).

The second example of a sample page from the Anders Berch Collection shows: ’Samples of Padua ribbons manufactured 1758 in Stockholm’. At this time, Stockholm had six silk ribbon mills, which according to research by the Nordic Museum, ‘… had a total of altogether 58 looms and 150 workers’. Padua ribbons were woven of coarse silk, resulting in rough, non-slippery ribbons, often used in clothing and particularly popular for tying two ribbons into a bow. The three sets of ribbons in three widths have been preserved together with original 18th century explanations of each sort. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:19A. Digitalt Museum).The trade of textile goods, domestically and abroad, was, in any case, considerable in Sweden, which can be studied in Carl Magnus Könsberg’s book on trading commodities, dated 1768. That publication is arranged like an encyclopaedia from A to Z and provides a fascinating insight into the profusion of desirable trading commodities in circulation. From which ’Band’ will be quoted in an English translation to give a glimpse into the manufacturing of ribbons in other European countries, simultaneously as this 18th century author had doubts about the necessity to import such wares.

- ‘Ribbons are manufactured in many places in the world. A multitude of Silk ribbons is woven in Basel. In Halle in Saxony, ribbons are made of Gold and Silver, after French patterns. The same happened in England and Italy. Silk ribbons are produced in Paris, Lyon and Tours. Twined Linen ribbons are acquired from Holland and Flanders. Woollen ribbons are manufactured in Amiens and some places in Piccardie. A great deal of various kinds of ribbons is manufactured in Sweden, so it doubtlessly seems unnecessary to import them from abroad.’

Rightly so, at this period, ribbons and bands were produced in significant quantities as both handicrafts and by textile manufacturers in Sweden. To be used within the household settings where such textiles were made, in rural as well as urban areas or sold via local trade or itinerant pedlars around the country. This domestic trade was supplemented by imported goods via the Swedish East India Company and other foreign trading together with smuggling to an unknown extent. These small trims were essential accessories for clothes and home furnishing and had multifaceted societal aspects. First and foremost, ribbons had practical functions: the ability to beautify and decorate when used for everyday wear or festive garments, equally as to demonstrate one’s standard of living – for instance, to have the ability to display wealth and luxury via visible ribbons made of silk, gold- and silver threads on garments. Other matters which had to be taken into consideration could be fashionable preferences or staying within local traditions, over time to weaving and collecting for a young woman’s dowry, to abide by varied rules for the difference between married and unmarried women’s dress but also the necessity to follow sumptuary laws which effected different strata of society in various ways. Overall, “moderation” in clothing within everyone’s means according to status was considered an important concept in 18th century Sweden.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Chapter of: ‘Carl Linnaeus’ Observations of Raw Materials and Textiles’ pp. 285-344).

- Könsberg, Carl Magnus, Kort anwisning på in och utrikes handelswahror såsom apotheques saker, ädla stenar, wijner, spetserier, färggräs, frukter, siden, linne, ylle och bomulstyger..., Norrköping 1768.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749… Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Linnés Dalaresa – Iter Dalecarlicum, Stockholm 1953.

- Lund University Library, Special Collection, Sweden. (Research visit in 2018: a study of the rare book by Könsberg… 1768).

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990. (Information, ribbons in Anders Berch Collection no. 156 & 157 a-j, pp. 209-213 & 260-261).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...