ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

SECOND-HAND CLOTHES & THE RAG TRADE

– 1810s to 1910s in Whitby

Collectors and gatherers of rags, merchants, pickers and rag-and-bone men had long played an important part in the recycling of textiles in Whitby. It was never difficult for second-hand clothes to find a new home, while large discarded pieces of fabric could be useful for making children’s clothes, patchwork quilts, or whatever else might be needed in the home. Smaller remnants could be unravelled by hand – especially in the case of wool – then carded and spun into yarn for weaving into cloth or knitting into sweaters. It could also be done by machine in the ‘shoddy industries’, but not locally, which recycled large quantities of rags into new fabric. Not least, scraps of fabric of all kinds were also an essential ingredient in the manufacture of good-quality paper in pre-industrial times up until the last decades of the 19th century.

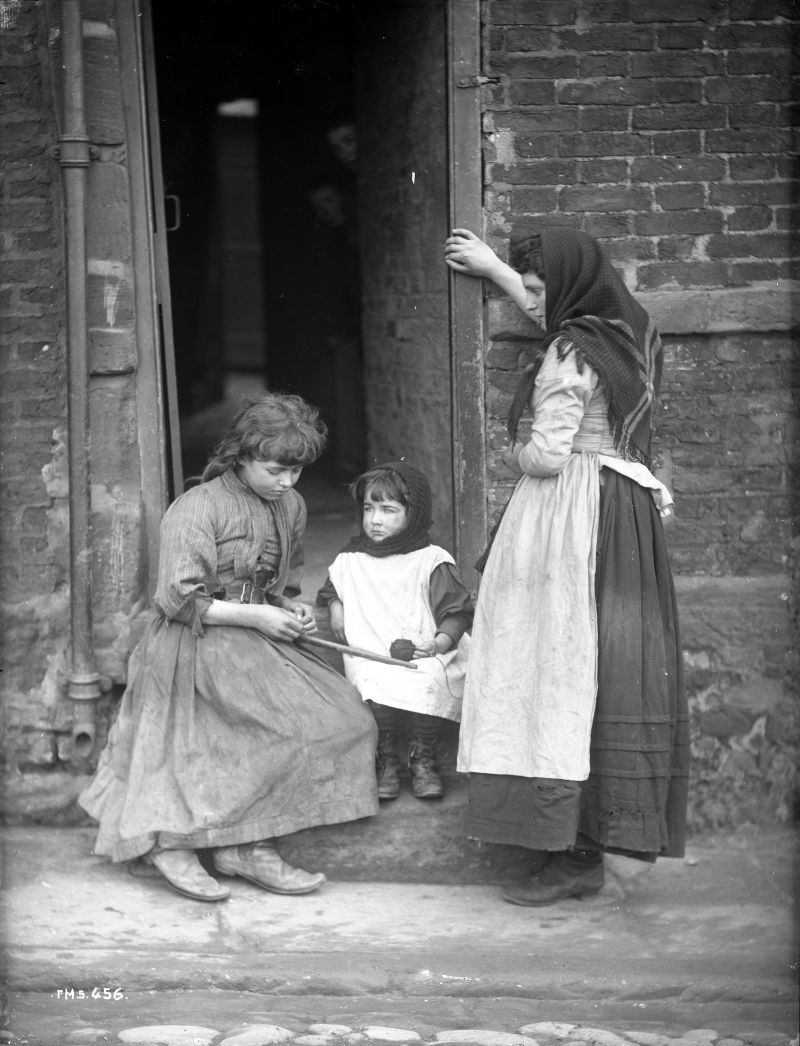

Church Street in Whitby. Successive censuses reveal that most rag gatherers lived along this street. Photo by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, 1890s. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photo Album 4/9).

Church Street in Whitby. Successive censuses reveal that most rag gatherers lived along this street. Photo by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, 1890s. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photo Album 4/9).The census returns of 1841, and thereafter every ten years until 1911, do give information about rag merchants in the Whitby area. These are variously described as rag maker, rag collector, rag merchant, rag warehouse, and rag gatherer. Though the term ‘rag gatherer’ could be ambiguous, either indicating a person who collected rags, or someone working in a textile factory whose job was to disentangle yarn caught in the machinery. However, the second definition is not relevant to Whitby since the town produced no industrial weaving between 1871 and 1901, the period when this description most often appears in the census.

The 1841 census listed one man living on Church Street as a ‘Rag Gatherer’, while ten years later, two women were listed as traders in rags. These were 16-year-old Henrietta Boyd, described as a ‘Collector of Rags’, and the 74-year-old widow Margaret Foster, a ‘Rag Maker’. It is unknown whether these two women worked together, as they had different work descriptions and lived in different parts of the town. The description ‘Rag Maker’ is also unclear, since it could imply either that the woman in question unravelled rags to re-use the yarn, or that she made rag rugs for a living. In the 1861 census, the number of persons trading with textiles and sewing had increased, and as a result, a wider range of fabrics was now commercially in circulation. This would presumably also have led to an increase in the quantity of rags and discarded clothes available and, consequently, in the number of people who found work dealing in rags. Moreover, the four persons now recorded as employed in this way may well have co-operated since they lived close together. The 52-year-old widower Stephen Connelly is listed as a ‘Rag merchant’ in Church Street, while in nearby Kiln Yard, there was a ‘Rag ware-house’ described as ‘unoccupied’ – this would have been a place where rags could be collected for wider distribution. Collecting of this kind was done by two sisters, Ann and Judea Dixon, who lived in Henrietta Street and both gave their occupation as ‘Rag collector’. Also living in Church Street was the 50-year-old widower Michael Kilmartin who worked as a ‘Rag and bone dealer’. Kilmarten may perhaps have worked with the other three, but his business would also have taken him further a field.

As a comparison to the rag workers included in the censuses of Whitby, Henry Mayhew (1812-1887) was a researcher into life and working conditions in London. His extensive work was based on walking the streets of the capital in the 1840s and 1850s, when he wrote down everything of interest in the speech of the people he interviewed. He recorded many informative comments on the conditions for textile workers. For instance, he noticed that rag gatherers were exceptionally poor, and since they were often themselves dressed in rags he considered them the poorest of the poor. This rag gatherer was illustrating his work ‘London Labour and the London Poor’ in 1851. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain).

As a comparison to the rag workers included in the censuses of Whitby, Henry Mayhew (1812-1887) was a researcher into life and working conditions in London. His extensive work was based on walking the streets of the capital in the 1840s and 1850s, when he wrote down everything of interest in the speech of the people he interviewed. He recorded many informative comments on the conditions for textile workers. For instance, he noticed that rag gatherers were exceptionally poor, and since they were often themselves dressed in rags he considered them the poorest of the poor. This rag gatherer was illustrating his work ‘London Labour and the London Poor’ in 1851. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain). The 1871 census in Whitby again listed four people working in the rag trade, but made no mention of any ‘Rag warehouse’, ‘Rag merchant’ or ‘Rag and bone dealer’. This time, four new people were listed, three of them living on the lanes of Church Street. These included a 45-year-old widow and a 70-year-old man who were rag gatherers and a 57-year-old married man who described himself as a rag collector. The fourth person was a man of 60 who lodged at an address in Wade’s Yard of Baxtergate and is listed as a collector. ‘Collector’ and ‘Gatherer’ were probably merely different terms for the same occupation. The 1881 census lists two more people working with rags and old clothes compared with ten years before. Of these six, three are described as ‘Rag Dealer’ and three as ‘Rag Gatherer’ all lived in the densely populated area that included Church Street and its adjoining lanes. There were three ‘Rag dealers’ in Kelly’s Yard: John and Mary Grier, a married couple both 32 years old, who had five children aged between 6 months and 11 years to support, and they worked with John’s father, 70-year-old William Grier. Another married couple also living in the Kelly’s Yard gave their occupation as ‘Rag gatherers’. These were Charles Waring, 58, and his 48-year-old wife Bridget, who shared her choice of occupation with a 60-year-old widow called Catherine Lofthouse, who lived in a neighbouring lane. If this increased trading in rags was the result of a period of exceptionally high poverty, or simply because more fabric now happened to be in circulation is uncertain. However, it is clear that trying to earn an income from trading in rags was restricted to the poorest members of society, since the persons named in the census inhabited streets and lanes with an exceptionally dense concentration of population, and since the same names never appear again ten years later. This was not work anyone would undertake if they could avoid it. Many of those who dealt in rags were also elderly, as if they saw the rag trade as an opportunity of continuing to earn money in old age. It must also be borne in mind that the work was not just dirty, but generally accepted as extremely unhealthy, spreading diseases, fleas and lice. An article published in The British Medical Journal on 13 August 1887 graphically illustrates the dangers rag workers were exposed to in many places:

- ‘In 1881, whilst investigating some outbreaks of small-pox amongst rag-sorters at a paper-mill at St. Mary Cray, Dr. Parsons, one of the inspectors of the Local Government Board, collected some valuable information on the general question, and this was published in the eleventh report of the Board’s medical officer. Since that time several other outbreaks of small-pox among rag-sorters in several parts of the kingdom have from time to time been recorded, and in reporting on the latest of these outbreaks, which occurred at Ivybridge towards the close of last year, Dr. Parsons has used the opportunity to revise his former report on the general subject. His recent experiences have not, however, enabled him materially to add to or modify the conclusions he arrived at in 1881.

- To prevent the introduction of cholera, the importation of rags from infected foreign places has been enforced in recent years as occasion has required, but this precaution is inapplicable as regards indigenous disorders, such as small-pox, the disease which has been found to be the most likely to be conveyed in rags…’

This photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe shows what was a reality for many Whitby families about 1900 – not only individuals occupied in the rag trade. The ragged clothes of the children outside the door of their home exemplify the varied garments of the children of the poor at various ages. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe A19.)

This photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe shows what was a reality for many Whitby families about 1900 – not only individuals occupied in the rag trade. The ragged clothes of the children outside the door of their home exemplify the varied garments of the children of the poor at various ages. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe A19.) The census returns of 1891 and 1901 show a distinct change since, in each of these years, only one person is listed as active in the rag trade. In 1891 this was the 49-year-old rag gatherer Edward Turner who lived in Boghole and in 1901 the 40-year-old rag and bone merchant Edward Roe in Chapels Yard, Church Street. In 1911, no one was listed as rag gatherers or dealers, but a few men were engaged in the rag and bone trade. Of these, Alexander Waring, 50, ‘Rag and Bone Dealer’ and John Jackson, 45, ‘Rag and Bone Collector’ most likely worked together since they both lived in Bolton’s yard off Church Street. Perhaps Frederick Cook, 31, who lived nearby in Elbow Yard, Church Street, was also part of their team – although he may have been a competitor. The decline of this trade in the last three censuses researched was caused mainly by the fact that in the last 10-15 years of the 19th century and afterwards, rags were no longer much used in the manufacture of newspapers.

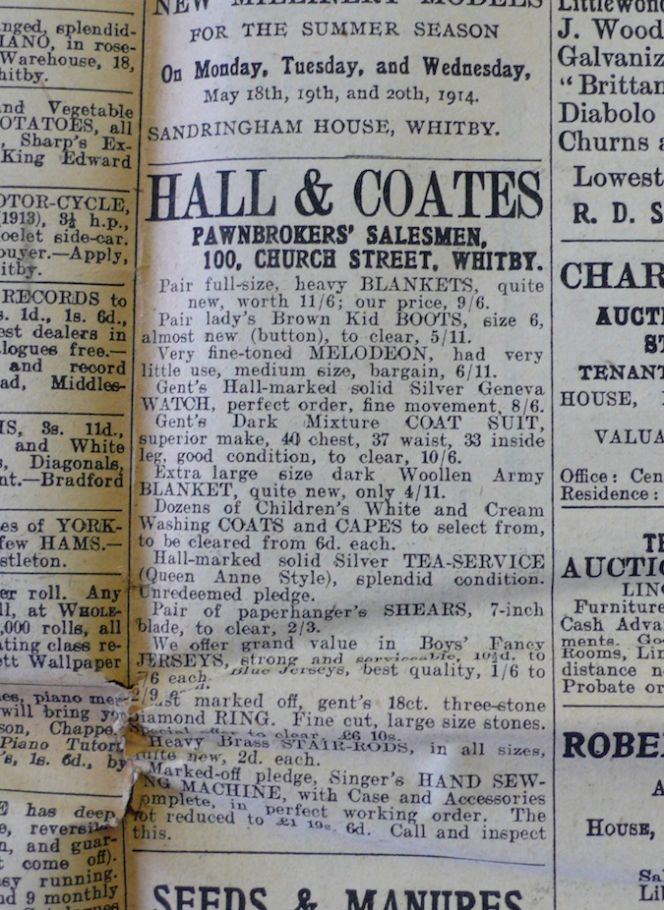

Very few census entries mention the second-hand selling of fabric/pieces of cloth or discarded clothes as an occupation; so those who did this work must have also been involved with other activities. The 1881 census is an exception since it includes two ‘Secondhand Cloth Dealers’ and a ‘Secondhand Cloth Shop’. Other individuals occupied with second-hand clothes dealing can be traced via advertising in the Whitby Gazette, like ‘Hall & Coates Pawnbrokers’ Salesmen at Church Street’, in 1914 for second-hand clothing and home textiles among other goods. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1914, April-June.) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

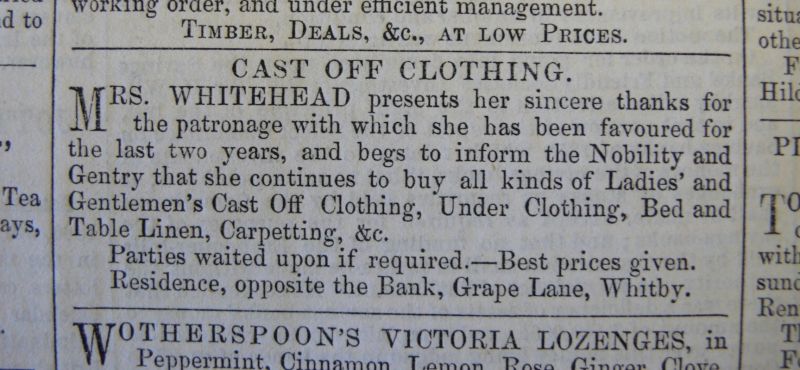

Very few census entries mention the second-hand selling of fabric/pieces of cloth or discarded clothes as an occupation; so those who did this work must have also been involved with other activities. The 1881 census is an exception since it includes two ‘Secondhand Cloth Dealers’ and a ‘Secondhand Cloth Shop’. Other individuals occupied with second-hand clothes dealing can be traced via advertising in the Whitby Gazette, like ‘Hall & Coates Pawnbrokers’ Salesmen at Church Street’, in 1914 for second-hand clothing and home textiles among other goods. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1914, April-June.) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.An earlier second-hand clothes trader advertising in Whitby Gazette was W. Grimshaw, Outfitter &c., &c. of Church Street; in December 1857, he announced: ‘Every description of new and second-hand Wearing Apparel constantly on sale’. This shop was obviously involved among other things with selling old clothes, and continued to do so until 1870 when Grimshaw stopped advertising. On the other hand his contemporary, Mrs Whitehead, concerned herself entirely with ‘Cast Off Clothing’ as shown below in this advertisement from spring 1860. She often advertised between 1860 and 1867, usually because she ‘Wanted to Purchase to any amount, Ladies’, Gentlemen’s and Children’s Cast off Wardrobes...’.

Whitby Gazette 1860, Mrs Whitehead, Cast off clothing. (Collection: Whitby Museum, The Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

Whitby Gazette 1860, Mrs Whitehead, Cast off clothing. (Collection: Whitby Museum, The Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.There can be no doubt that the second-hand market must have continued in this style, either through dealers who did not advertise or by selling used clothes through others of the town’s many clothes shops. But in fact, this kind of advertising stopped completely from 1870 to 1908 with the exception of Mrs Peacock, who in spring 1880 announced: ‘Wanted to purchase Cast-Off Clothing of any description in town or country. Parcels forwarded promptly acknowledged. Cash paid at once, by Mrs. J.E. Peacock, Church Street, near Cholmley School, Whitby’. Whilst Mrs P.W. Appleton first advertised in 1909-1910 from her premises in the same street, as ‘Successor, to the late Mrs. Feeley, give the best prices for Cast-off Clothing, Boots, Shoes, etc.’. A business in Loftus also advertised during 1909-1913, describing itself in August 1910 as ‘Mr. & Mrs. Reynolds, 55, High Street, Loftus (late of Whitby) Buy Ladies’ and Gentlemen’s Cast-Off Clothing. Parcels by rail or post receive immediate attention, Note. We visit Whitby first Tuesday in every month.’ This indicates that both these enterprises had been active in the field before 1909, either as successors to earlier traders or simply after moving to a new address.

Earlier information about second-hand clothes can be traced in George Young’s publications of 1817, 1824 and 1840. Young’s 1817 book on Whitby, for example, gives interesting details on the tradesmen and manufacturers of the day, including ‘6 slop-shops’ – that is to say, shops that sold inexpensive or good-value second-hand clothes. Additionally, the three directories published between 1823 and 1864 included people active in Whitby as dealers in second-hand clothes. Baines’s Directory (1823) lists three women under ‘Clothes Brokers and Dealers’: Ann Lincoln, Elizabeth Weir and Ann Wherritt. While Pigot’s Directory (1834) mentions under ‘Clothes Dealers’: Ann & Jane Coupland, George Lockey and Thomas Wilson. And Slater’s Directory (1864) includes under ‘Clothes Dealers’: Elizabeth Chapman, Sarah Weatherill and William Whitehead. No information about the professional lives of these people is known in any other contemporary documents, nor are they listed in the censuses of either 1861 or 1871, but it can be assumed that such work would often have been done by women since only three of the nine listed above in the directories were men.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 53, 67 & 133-134, 329-333. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see this book).

- The British Medical Journal, ‘Public Health and Poor-Law Medical Service – The Spread of Infection by Rags’, Aug. 13, 1887.

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1841-1901 microfilm & 1911 digital).

- Whitby Museum, Library and Archive & Photographic Collection (Whitby Lit. & Phil.: Whitby Gazette, 1860-1914 & two photographs).

- Young, George, A History of Whitby, Vol. I-III, 1817.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE