ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

SHIP REGISTERS AND OWNERSHIP

– A Business involving Textile Traders in Whitby: 1780s to 1914

The extant Ship Registers from 1786 to 1914 reveal that it was possible for the most successful sailmakers themselves to own ships registered in Whitby. This was usually in the form of a joint ownership shared between several interested parties and sometimes involving other groups of local textile workers such as linen manufacturers, tailors, weavers, drapers and hosiers. These textile shop owners and craftsmen involved with Whitby seafaring, via such a shared ownership basis, most obviously had chosen to be incorporated for economic reasons. But maybe also for other reasons, like being part of a traditional business culture in a coastal town or even from an emotional perspective to have a tighter connection to the sea. This essay will be assisted by a wide range of contemporary handwritten documents, local maps and prints as well as photographs linked to these particular textile traders.

A view across the Whitby upper harbour, taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in the 1890s. The atmospheric photograph visualises the typical variety of schooners, brigs, sloops and rowing boats in this small town harbour – where River Esk empties into the North Sea. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-48, part of photograph).

A view across the Whitby upper harbour, taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in the 1890s. The atmospheric photograph visualises the typical variety of schooners, brigs, sloops and rowing boats in this small town harbour – where River Esk empties into the North Sea. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-48, part of photograph).Three-masted ships and earlier ship models can without doubt be linked to the textile traders via the extant Ship Registers though, to be introduced with William Chapman. He was the sailmaker and linen manufacturer whose name occurs most often at the end of the 18th century since he had shares in a considerable number of ships, among them: 1797 Thomas & Alice, Pacific, 1798 Hannah, Edward, Emerald and John, in 1799 Benjamin & Mary and Liberty. Other sailmakers of the time who invested in the shipping business were, in particular, John Holt with Thalia (1798) and Robert Hunter, who had a share in the ships Margaret and John (both 1802). Meanwhile, Joseph Addison remained involved over a longer period, with Maria (1803), Ann (1818) and Muta (1820-1833). His son William Addison followed in his father’s footsteps and, among other things, features as one of the owners of the Margaret (1841). Other Whitby sailmakers who participated in the town’s shipping trade were Robert Cropton and Anthony King during the 1830s, George Pyman with ‘27/64 parts’ in the Peace 1854, and George Gallilee with shares in a number of ships during the 1860s to 1880s.

A closer observation of the sailmaking traditions in Whitby via historical documents gives evidence for the recurrence of the same family names for sailmakers during more or less the whole period of sail-weaving. This is also seen in the fact that sail lofts were closely involved with sail manufactories during this peak time, as also pointed out by George Young in his book about Whitby printed in 1817: ‘There are four sail-lofts, or sail-manufactories, at present in Whitby, carried on respectively by Messrs. Wm. Chapman, John Holt, Junr. Jos. Addison, and Harrison Chilton: the first situated in Baxtergate, the next two in Church street (located where the chimney smoke is as most intense on the photograph above), and the last on the Crag.’ Chilton’s business, with premises in an alley leading from Church Street, is also linked to an apprenticeship indenture for the next generation of sailmakers in the family: this was for Thomas Chilton in Whitby in 1822; he is also listed in the Poor Law Valuation of the town in 1837, which states that Thomas Chilton owned an ‘office & 2 floors, sail-loft &c, £11’ at Cock Pit Yard. Also listed in this valuation was Joseph Addison’s ‘Ground-floor warehouse, first floor do, sail-loft and office and loft over, £22’ in the same yard, while at Long Steps and Boulby Bank the sailmaker John Irvin rented a ‘loft above, £3’ plus three parts of a larger property owned by William Chapman in Baxtergate. The greater part of this property was used by William himself together with John Chapman ‘sail-loft & office £31’ while the other two parts were both described as ‘warehouse under sail-loft’.

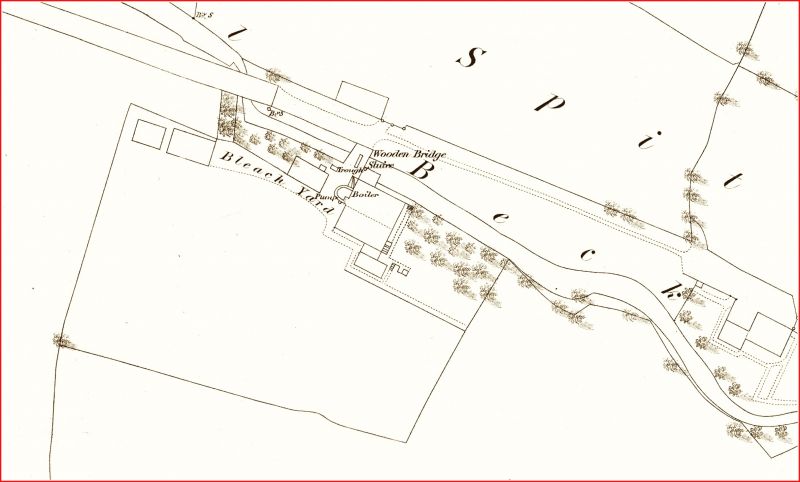

Whitby map surveyed in 1849, close-up image of Sail Cloth Manufactory, Mr Chapman’s Bleach yard. A family, who was involved in the ownership of ships over several generations. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Map Collection).

Whitby map surveyed in 1849, close-up image of Sail Cloth Manufactory, Mr Chapman’s Bleach yard. A family, who was involved in the ownership of ships over several generations. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Map Collection).Chapman’s business at Spital Bridge, which can be seen so clearly on the map illustrated here and surveyed in 1849, also appears here with a ‘No 1 Sail Loft’ together with another sail loft situated opposite Ship Yard. Both these were conveniently near the River Esk. To be a sailmaker also involved being accepted as a respectable craftsman – as was the case with many other occupations – and this can be seen in a deed of trust drawn up in September 1843. This involved the sailmaker Samuel Andrew as one of the Trustees of the Whitby Temperance Society together with shipowners, shipbuilders, ropers, weavers, a master mariner, a bookseller, and others, in setting up rules concerning the purposes for which the hall could be used both on working days and ‘the Lord’s Day’. The occupation of sailmaker also survived considerably longer than that of sail-weaving – made possible by canvas bought from elsewhere – since a few practitioners still appear as late as the 1911 census. This is why despite the fact that sails were woven by only a few during the 1860s, no less than twenty were still active in sewing them. These men can be followed through censuses and directories, and an apprenticeship indenture from 1864 involving the sailmaker George Galilee, and the announcements in the Whitby Gazette. That sailing ships and steamships now worked side by side for several decades appears among other things from notices and announcements in the local paper, even though there were still as many sailmakers as during the preceding decade, information and announcements to do with sails became rarer from the 1870s onwards. That sailing ships were on the way to taking a smaller role in Whitby harbour is made clear by the introductory notes to an insurance company for Iron Steamships, described as follows in the Whitby Museum Library and Archives’ catalogue: ‘The Whitby Mutual Marine Iron Steamship Insurance Co and the Whitby Iron Steamship Insurance Co were established in 1873 and incorporated as limited companies in Feb. 1876 for the mutual insurance of steamships insured by the members of the companies.’ The 1881 census makes it even clearer that this trend was a fact, since by then only half the previous number of sailmakers were still left in Whitby.

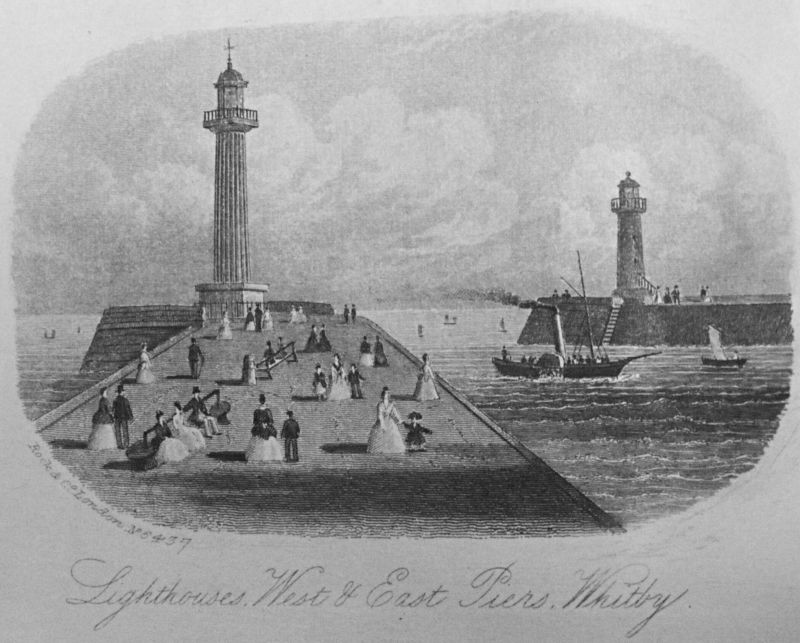

‘Lighthouses West & East Piers Whitby’ c. 1860s. At this time steamships coexisted with sail in Whitby harbour, as can be seen in this print. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Local Prints and Papers, 942.747) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

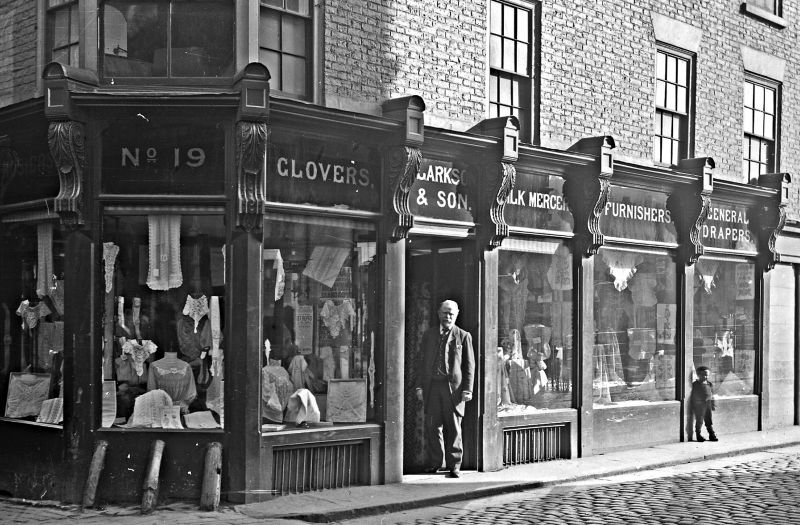

‘Lighthouses West & East Piers Whitby’ c. 1860s. At this time steamships coexisted with sail in Whitby harbour, as can be seen in this print. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Local Prints and Papers, 942.747) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.  A number of drapers can be found in the local directories of the 1820s and 1830s, including in 1823 and 1834 William Clarkson, who was part of the shared ownership of local ships as noted below – whose son and grandson later ran the firm of ‘James N. Clarkson & Son’, a frequent advertiser in the Whitby Gazette between 1855 and 1907. Possibly the man standing in the shop doorway in this picture taken circa 1900 – is Thomas Clarkson himself; he would have been a good fifty years old by now. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection. Photo by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe. 28-33, part of photograph).

A number of drapers can be found in the local directories of the 1820s and 1830s, including in 1823 and 1834 William Clarkson, who was part of the shared ownership of local ships as noted below – whose son and grandson later ran the firm of ‘James N. Clarkson & Son’, a frequent advertiser in the Whitby Gazette between 1855 and 1907. Possibly the man standing in the shop doorway in this picture taken circa 1900 – is Thomas Clarkson himself; he would have been a good fifty years old by now. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection. Photo by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe. 28-33, part of photograph). Tailors could also be involved in ship ownership, notably Thomas Wilson (1802) and Thomas Dotchon during the 1810s, while the latter’s son William Dotchon frequently held shares in sailing ships, especially in the 1840s. It has also been possible to trace some weavers in these registers, such as George Myres as part-owner of the Cambrian in 1818 and Robert Davison of the Autumn (1820). Drapers among the shipowners can most easily be identified among the owners of the larger drapers’ shops, who often advertised in the Whitby Gazette. For example, the draper William Clarkson was one of the owners of the Worksop (1831) and Clio (1832), while John Lawson owned ‘48/64’ of a ship named after himself, the John Lawson. With the expanding group of steamships in the 1850s, it became rather more unusual for anyone other than ‘shipowners’ to be joint-owners, and when this did happen, it usually involved more joint-owners, each with fewer shares than before. This can be seen in 1879 in the case of the ship Annie, with the three drapers Robert Wellburn, John Maston and John Wellburn each owning a 1/64th part of this ship. Robert Wellburn also owned a small part of the Crescent (1879) and Rosehill (1884), while, finally, the frequently-advertising Whitby hosier John Trowsdale appeared as a joint-owner of the ship Concord in 1902.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 163-164 & 178-179).

- The National Archives at Kew, London (1837 Poor Law Valuation Whitby, MH12/14656).

- Whitby Gazette, 1855-1914.

- Whitby Museum (Whitby Lit. & Phil.), Whitby. | Library & Archive (Whitby Gazette, Ship register, 1786-1914; transcription from National Maritime Museum & various historical documents linked to the sea. See the book of Hansen, V... for a full list of sources). | Photographic Collection (Local photographs 1880s-1914). | Map Collection.

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library. (Census from Whitby and Ruswarp; 1841, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891 & 1901, microfilm. Census 1911, online).

- Young, George, A History of Whitby, Vol. I-II 1817.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE