ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

SILK AND SERICULTURE: 1740s to 1770s

– Observations, Experiments and Plantations with connections to Pehr Kalm, Benjamin Franklin et al.

The interest to introduce sericulture in Europe and the North American colonies during the 18th century – to be able to weave fine silks of domestically produced raw material – increased despite the many obstacles with the rearing of silkworms and planting of mulberry trees in unsuitably cold climates. Such aims and hopes can be revealed via contemporary travel journals, correspondence, artworks and various historical documents. This essay will foremost look closer into one of Carl Linnaeus’ Apostles, via the naturalist Pehr Kalm’s reflections in North America around the year 1750 and his continuous work over decades to come with the rearing of silkworms for the purpose of the production of silk in Finland. To be compared with the slightly later notations and correspondence on sericulture by Benjamin Franklin, together with such writings and practical work by other individuals in their network. Furthermore, these two men met frequently in Philadelphia and regarded each other as friends during Kalm’s stay in the area over three winter periods from 1748 to 1751.

Portrait in oil on canvas, thought to represent Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), painted around 1764 by J. G. Geitel. (Courtesy of: Satakunta Museum, Björneborg, Finland).

Portrait in oil on canvas, thought to represent Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), painted around 1764 by J. G. Geitel. (Courtesy of: Satakunta Museum, Björneborg, Finland).Pehr Kalm was the apostle of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) who, with the greatest determination, argued his ideas and concerns on sericulture in his observations in North America (1748-51) as well as in his later painstaking experiments with trial plantations in Finland over several decades after his voyage. He was somewhat disappointed, however, that the settlers, during his travels in the colonies, showed such a feeble interest in the “European dream” of silk. The Americans were, nevertheless, curious about the potential of silk already before the year 1750, something that was noted in John Bartram’s (1699-1777) description from September 1748 included in Kalm’s journal. This observation was linked to a governor in Connecticut [Jonathan Law 1741-50] whose farm was situated north of New York and continues: ‘…it is evident however, that silk worms succeed very well here, and that this kind of mulberry trees is very good for them. The governor brought up a great quantity of silk worms in his court yard, and they succeeded so well, and spun so much silk, as to afford him a sufficient quantity for clothing for himself and all his family.’ This recording turns out to be the only example Kalm could refer to, and he had not even seen the production with his own eyes. Despite the difficulties of finding proof that sericulture was profitable and useful, Kalm’s preoccupation with the issue continued for a long time. As late as 1776, nearly 30 years later, he even published his findings on the subject under the title ’Beskrifning på Norr-Americanske Mulbärsträdet, Morus rubra kalladt’ (Description of the North American Mulberry Tree, called Morus rubra). There, he noted that the trees grew and thrived in the forests of Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania and the southern part of New Jersey, more sparsely further north and then ceasing altogether.

It has to be added nonetheless that Kalm’s hope for an increased silk production domestically in the North American colonies/states was realised on a more momentous scale in the second half of the 18th century, not least through the initial work of Governor, Jonathan Law (1674-1750), noted in Kalm’s journal. During the final year of his life, Mr Law succeeded moreover in getting a piece of Parliamentary legislation passed, entitled ‘Act for Encouraging the Growth & Culture of Raw Silk in His Majesty’s Colonies or Plantations in America’. Studies into North American sericulture show that this manufacture was further developed in New England by Ezra Stiles (1727-1795), as described in research by historian Ben Marsh. With excellent assistance from his household, Mr Stiles presented in 1763 his experiments with 3,000 silkworm eggs, and the enterprise continued to be developed over more than thirty years; and thanks to his meticulously kept silkworm journals, posterity can now study that branch of American textile growth.

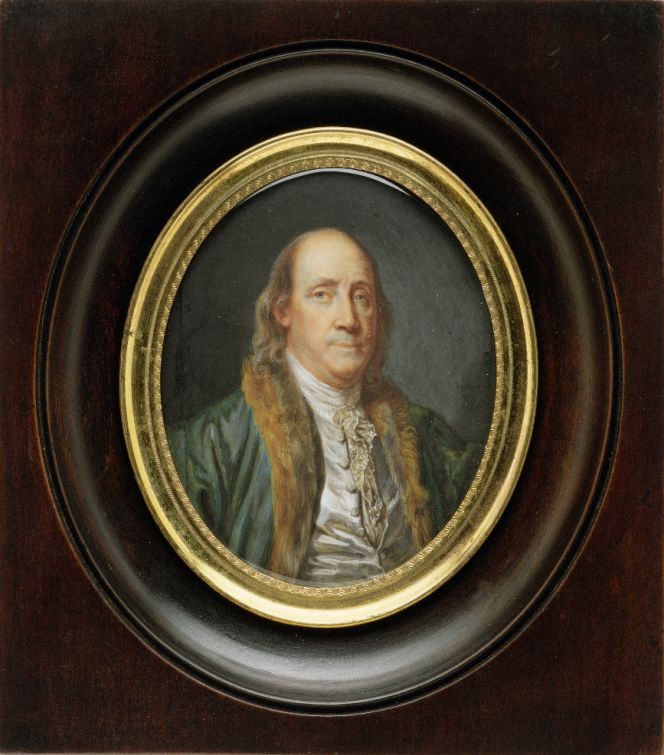

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), after a Painting by Greuze in 1777. This depiction was made slightly later than his correspondence linked to notes on silk, but it seems like he as most people of influence had a personal interest or desire to wear fine fabrics woven of silk. Due to that he was portrayed in a fur-edged silk or woollen coat and a waistcoat of shiny silk material. (Courtesy of: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US. No: 68.222.9).

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), after a Painting by Greuze in 1777. This depiction was made slightly later than his correspondence linked to notes on silk, but it seems like he as most people of influence had a personal interest or desire to wear fine fabrics woven of silk. Due to that he was portrayed in a fur-edged silk or woollen coat and a waistcoat of shiny silk material. (Courtesy of: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US. No: 68.222.9).A closer look into some of Benjamin Franklin’s rich correspondence during the years 1769 to 1772 reveals that he wrote several letters during this period in London to the Philadelphia physician Cadwallader Evans (1715-1773) about silk and possible ideas for future sericulture in the North American colonies. Initially, on September 7th 1769, when he emphasised the management of silkworms learned via French writings, how the cocoons would not be spoiled on the long sea journey to the colonies, the Italians' traditions on the subject, etc and he continued optimistically:

- ‘There is no doubt with me but that it might succeed in our country… But mulberry trees may be planted in hedgerows on walks or avenues, or for shade near a house, where nothing else is wanted to grow. The food for the worms, which produce the silk, is in the air, and the ground under the trees may still produce grass, or some other vegetable good for man or beast. Then the wear of silken garments continues so much longer, from the strength of the materials, as to give it greatly the preference. Hence it is that the most populous of all countries, China, clothes its inhabitants with silk, while it feeds them plentifully, and has besides a vast quantity, both raw and manufactured, to spare for exportation…’

In a letter dated July 4th 1771, Franklin pointed at the various prices of the cocoons and admired the perfection of Italian silk; he also added:

- ‘I communicated your thanks to Mr. Walpole, who was pleased to assure me he should always be ready to afford the design all the assistance in his power, and will endeavour to procure some eggs for you from Valencia against the next season…’

Just two weeks later, on July 18th 1771, a new letter was sent to Cadwallader Evans in which Franklin described the Indian as well as the Chinese traditions to perfect silk, from taking the best care of the mulberry trees, a gathering of the leaves, suitable latitudes and a recommendation of a book on the subject. ‘Du Halde has a good deal on the Chinese management of the silk business.’ That is to say, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde’s book Description de la Chine in French was printed in 1736.

A fourth letter on this subject was addressed to Cadwallader Evans on February 6th 1772, which makes it clear that ‘trunks of silk’ had been sent to London, presumably organised by Evans. Still, it is uncertain if this raw silk originated from Ezra Stiles’ plantation (mentioned above) or somewhere closer to Evans’ home in Pennsylvania. A few quotes will give an idea of the aims for such exclusive goods:

- ‘The trunks of silk were detained at the custom-house till very lately; first, because of the holidays, and then waiting to get two persons, skilful in silk, to make a valuation of it, in order to ascertain the bounty. As soon as that was done, and the trunks brought to my house, I waited on Dr. Fothergill to request he would come and see it opened and consult about disposing of it, which he could not do till last Thursday. On examining it, we found that the valuers had opened all the parcels, in order, we suppose, to see the quality of each, had neglected to make them up again, and the directions and marks were lost (except that from Mr. Parke, and that of the second crop), so that we could not find which was intended for the Queen and which for the Proprietary family. Then, being no judges ourselves, we concluded to get Mr. Patterson, or some other skilful person, to come and pick out six pounds of the best for her Majesty, and four pounds for each of the other ladies’.

- ‘Mr. Boydell, broker for the ship, attended the custom-house to obtain the valuation, and had a great deal of trouble to get it managed. I have not since seen him, nor heard the sum they reported, but hope to give you all the particulars by the next ship, which I understand sails in about a fortnight, when Dr. Fothergill and myself are to write a joint letter to the committee’.

- ‘Dr. Fothergill has a number of Chinese drawings, of which some represent the process of raising silk, from the beginning to the end. I am to call at his house and assist in looking them out, he intending to send them as a present to the Silk Company.’

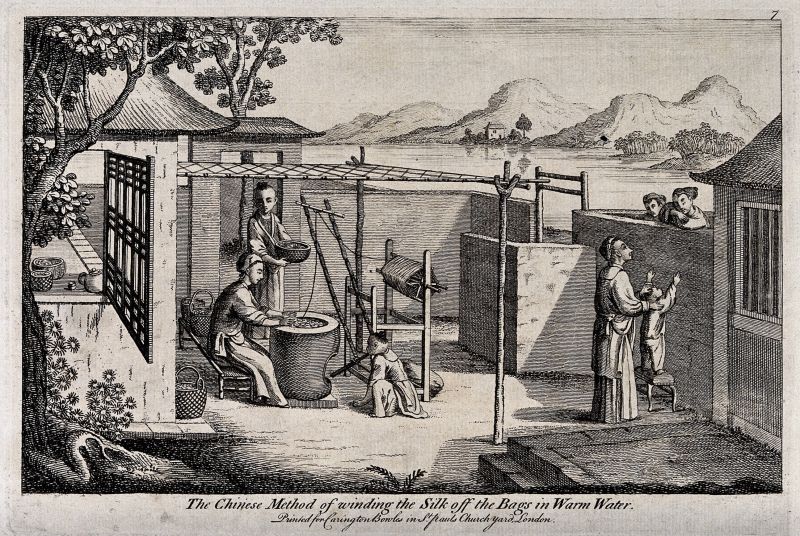

It is unknown if the Chinese drawings mentioned by Franklin (in the letter on 6th February in 1772) are still preserved, but nine engravings of silk manufacturing in China – originally presented by the publisher Carington Bowles (1724-1793) may be of similar appearance – dating from the 2nd half of the 18th century. Here exemplified with two images from the collection. ‘The Daily Practice of giving the Silk Worms fresh Leaves’ as the third stage of nine. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, UK. No: 44098i).

It is unknown if the Chinese drawings mentioned by Franklin (in the letter on 6th February in 1772) are still preserved, but nine engravings of silk manufacturing in China – originally presented by the publisher Carington Bowles (1724-1793) may be of similar appearance – dating from the 2nd half of the 18th century. Here exemplified with two images from the collection. ‘The Daily Practice of giving the Silk Worms fresh Leaves’ as the third stage of nine. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, UK. No: 44098i). Together with a second image of Chinese silk traditions, which demonstrates the process of reeling the silk from cocoons and winding the silk thread onto a reel. This work depicts the fifth stage of nine – from gathering the eggs to weaving complex silks. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, UK. No: 44100i).

Together with a second image of Chinese silk traditions, which demonstrates the process of reeling the silk from cocoons and winding the silk thread onto a reel. This work depicts the fifth stage of nine – from gathering the eggs to weaving complex silks. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, UK. No: 44100i).However, even before this period Franklin corresponded with Ezra Stiles in New England, who came to be one of the important individuals behind the silk cultivation in the late 18th century. Franklin wrote from Philadelphia, on December 12th 1763:

- ‘Dear Sir. According to my Promise I send you herewith the Prints copied from Chinese Pictures concerning the Produce of Silk. I fancy the Translator of the Chinese Titles, has sometimes guess’d and mistaken the Design of the Print, in his Account of what is represented in it. But of this you will better judge than I can. I have some Accounts of the Silk in Italy which I will, the first Leisure I have, transcribe and send you. I am with great Esteem, Dear Sir, Your most obedient humble Servant. B Franklin’

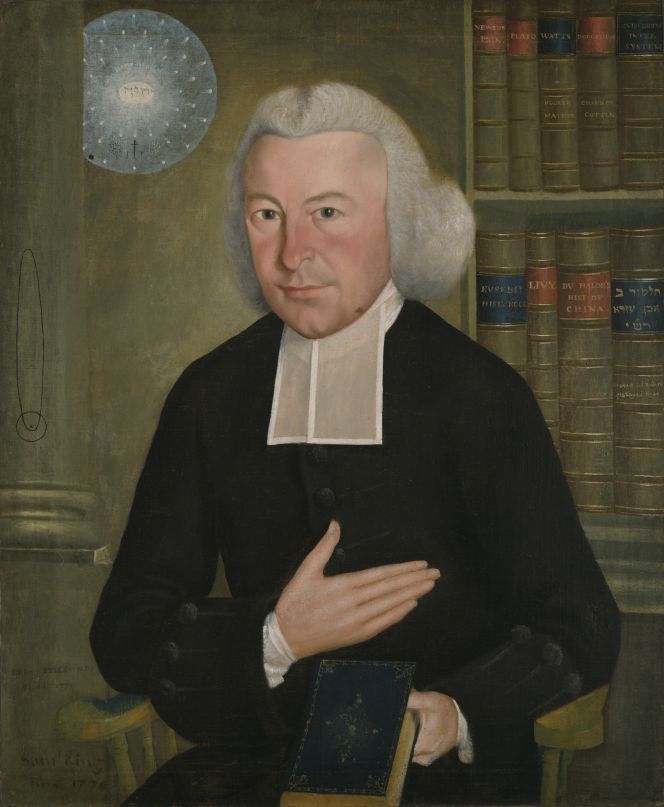

Portrait of the minister and author Ezra Stiles in 1770-71, during a time when he and his household worked with sericulture in Newport, Rhode Island (Courtesy of: Yale University Art Gallery, US. No: 1955.3.1).

Portrait of the minister and author Ezra Stiles in 1770-71, during a time when he and his household worked with sericulture in Newport, Rhode Island (Courtesy of: Yale University Art Gallery, US. No: 1955.3.1).According to research made by the University Library in Leipzig (via National Archive, Founders Online), Franklin visited Ezra Stiles in July 1763 at a time when his large-scale sericulture was introduced. A year later, on – June 19th 1764 – Franklin sent a new letter to Stiles and particularly emphasised the importance of the Chinese prints to get a better understanding of the complex process of sericulture. Of the ten preserved letters from Benjamin Franklin to Ezra Stiles, dated 1755-1767, these two included observations on silk only. The same Chinese drawings were mentioned in connection with Dr Fothergill in a letter to Cadwallader Evans in 1772 (cited above). Furthermore, Franklin discussed the same Chinese prints and detailed advice for silk manufacturing in ‘To the Managers of the Philadelphia Silk Filature’ in 1772, and extracts of this text were printed in The Pennsylvania Gazette on July 29 of the same year, as described by the National Archive, Founders Online.

Benjamin Franklin – regarded as a true polymath of his time – was formed of ideas, discussions and knowledge which stretched in many directions. However, his interest and engagement for silk seems to have ended in 1772, the year before Evans's death; due to that, it has not been possible to trace such remarks in Franklin’s correspondence or writings for the years that followed. From Pehr Kalm’s horizon the biggest problem was the extremely cold winters which occurred at even intervals, killing off large parts of the plantations in Sweden as well as in Finland. It is likely, therefore, that in his heart of hearts, just like the other advocates of this northerly sericulture, Kalm realised that after many years of hard and time-consuming work and with little to show for it, Nordic domestic silk production on a large scale was simply not possible. His project ended with him when he passed away in 1779, three years after his thesis, “Description of the North American Mulberry Tree, called Morus rubra”, had been published.

Sources:

- Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste, Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique, et physique de l'empire de la Chine…, 1736.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 31-60, Pehr Kalm’s observations on sericulture, part of this chapter).

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & Vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Kalm, Pehr, ’Beskrifning på Norr–Americanske Mulbärsträdet, Morus rubra kalladt’, Kungliga Vetenskaps Akademiens handlingar (KVAH) Vol. XVIII-XL 1757-1779. pp. 143-163, 1776.

- Marsh, Ben, ‘One man might bring it to perfection: Rev. Ezra Stiles (1727-1795) and the quest for New England silk in the 18th century’ The Textile Society, vol. 41, 2013-14 pp. 4-12, Cheshire 2014.

- National Archive, Founders Online, Letters from Benjamin Franklin to Ezra Stiles’, two letters 1763-1764 & Writing to the Philadelphia Silk Filature in 1772. (Quotes of text sections; accessed November 6, 2019).

- The Online Library of Liberty. Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, V. Letters and Misc. Writings 1768-1772 [1904]. (Quotes of text sections: accessed November 6, 2019).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE