ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

SOCIAL LIFE, TABLES AND EMBROIDERY

– at a Manor House in 1758

Writing tables, unpainted kitchen work surfaces, gate-legged dining and gambling tables together with sculptured and gilded models for decoration, etc. Just as today, tables were used for the most varied purposes during the 18th century. In this second essay based on one of my earlier book projects – about an Inventory at a manor house in southernmost Sweden – tables will be in focus. However, worktables used for embroidery or other handicrafts were not mentioned. This is unexpected when the 1758 inventory was written in such minute detail and contemporary as well as somewhat later estate inventories from the Piper family’s other manor houses listed sewing tables of various models.

This somewhat later depiction of a woman by her portable work-box, reveals her seemingly relaxed attitude to textile craft and her great interest for the latest most exquisite fashion. Portable work-boxes may also have been the natural choice for many women of the nobility, as boxes of this type easily could be transported together with personal belongings (not included in inventory lists) when they travelled between the family’s manor houses. Oil on canvas by unknown artist ca 1770s-1780s. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm Sweden. NM.0178153, Digitalt Museum).

This somewhat later depiction of a woman by her portable work-box, reveals her seemingly relaxed attitude to textile craft and her great interest for the latest most exquisite fashion. Portable work-boxes may also have been the natural choice for many women of the nobility, as boxes of this type easily could be transported together with personal belongings (not included in inventory lists) when they travelled between the family’s manor houses. Oil on canvas by unknown artist ca 1770s-1780s. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm Sweden. NM.0178153, Digitalt Museum).In 1758, it was the count and tenant in tail Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770) and his wife Ulrika Christina Mörner of Morlanda (1709–1778) who lived at Christinehof Manor House. This house was first and foremost used by the family and visiting friends during the summer and early autumn months. The couple had five children, whereof two grown-up daughters and three sons (11-26 years old). The youngest daughter – Christina Charlotta (1734-1800) – was widowed since 1756 with children, so it was probably only the mother and the unmarried daughter Ulrika Fredrika (1732-1791) who might have been embroidering at the summer residence. To what extent is unknown. The lack of sewing tables, etc., in the inventory may point to the fact that other activities were preferred during the warm season, that both women were not keen on handicrafts, or that other tables or portable work boxes were in use. Furthermore, only one quilted bedcover was listed in the Young Lady’s Chamber from the rich selection of textiles in various rooms in the grand house. (Together with marked linen, probably stitched by the housekeeper or other female servants). Contemporary or later (1754-1803) inventory lists or estate inventories studied from the same archive – all include a number of either embroidered furnishing textiles, sewing tables or other tools that were useful for textile handicraft.

Even if “all” girls of the nobility and bourgeois in Sweden, France and many other countries alike had learned the craft of embroidery, it is not realistic to assume that every woman liked or even embroidered regularly. ‘The diligent mother’ who learned her daughter useful textile crafts as embroidery and winding yard were true for some. Undated oil on canvas, ca 1740s-1750s, by Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 784, Wikimedia Commons).

Even if “all” girls of the nobility and bourgeois in Sweden, France and many other countries alike had learned the craft of embroidery, it is not realistic to assume that every woman liked or even embroidered regularly. ‘The diligent mother’ who learned her daughter useful textile crafts as embroidery and winding yard were true for some. Undated oil on canvas, ca 1740s-1750s, by Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 784, Wikimedia Commons).However, one proof that the lady of the house Ulrika Christina embroidered can be traced in a contemporary letter from the oldest son, Carl Gustaf, addressed to his father, Carl Fredrik Piper. The 21-year-old son was situated in Stockholm at this time, as he, since 1757, worked as a chamberlain for King Adolf Fredrik. He wrote: ‘My hope is that dear mother was satisfied with the yarn; at least Jana says that there is no better to be found and that it after washing will be rose-red, even if it now looks dark. She names it Turkish yarn.’ Embroidery was also often inspired by pattern books, which had been in continuous prints on the continent since the 16th century. The inventory lists no such books or no books at all, which suggests that books were regarded as personal belongings like clothing and, therefore, not included in an inventory of a manor house.

The number of tables in this large manor house in 1758 counted to around forty models of various uses. Here the three-storey Christinehof manor house seen from northeast. The façade was renovated in 1993 and restored to its original dark yellow colour (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons).

The number of tables in this large manor house in 1758 counted to around forty models of various uses. Here the three-storey Christinehof manor house seen from northeast. The façade was renovated in 1993 and restored to its original dark yellow colour (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons).A few examples of tables and the use of table linen may give an idea of the rich variation of this piece of furniture. The ‘dining tables’ were ‘quadrangular’ (3) and ‘half round’ (2), all placed in the Hall on the first floor where the family probably had most of their meals. These tables were also mentioned as brownish painted and foldable, so there was no need for any decorations or finer woods, whilst these tables were covered with linen cloths when in use. Linen woven in damask and damask diaper techniques were also listed in the inventory.

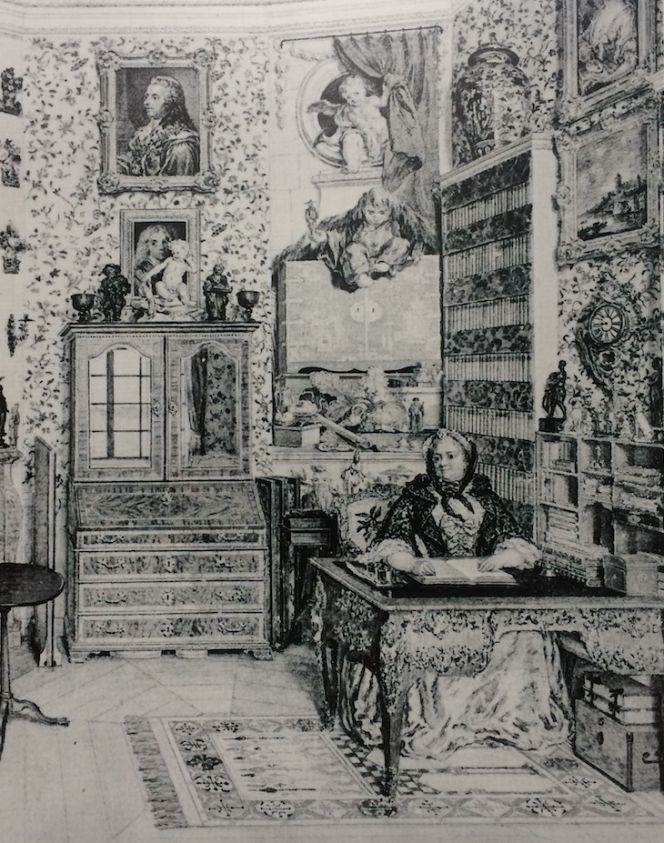

The countess Ulla Tessin writing at her desk in a cabinet at Åkerö manor house, ca 60 kilometres from Stockholm. This watercolour was painted in 1763 by Olof Fridsberg (1728-1795). In the very detailed depiction – here in black and white – we may get an idea of how a writing cabinet at Christinehof was furnished. Though probably somewhat more modest judging by the detailed inventory, compared to this particular noble home, meaning less ornaments and without imported hand-knotted floor carpets. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMH 145/1960).

The countess Ulla Tessin writing at her desk in a cabinet at Åkerö manor house, ca 60 kilometres from Stockholm. This watercolour was painted in 1763 by Olof Fridsberg (1728-1795). In the very detailed depiction – here in black and white – we may get an idea of how a writing cabinet at Christinehof was furnished. Though probably somewhat more modest judging by the detailed inventory, compared to this particular noble home, meaning less ornaments and without imported hand-knotted floor carpets. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMH 145/1960).A model that seems to have been more noticeable was the ‘tea table’ (2), which were placed in the Countess’ Drawing-room and the First Drawing-room on the first floor. One example was mentioned as ‘round’ whilst the other was ‘blue lacquered’, furthermore one of the many additional notes in the inventory reveals that a ‘red table’ had been taken to Christinehof manor house in 1768, probably also a lacquered model. This type of coating with lacquer was popular in wealthy homes during most of the 18th century; if the tables at Christinehof were of East Indian origin or maybe Dutch, English or Swedish-made, were not mentioned in the inventory. However, it was possible to buy lacquered furniture in Stockholm, among others, at ‘The East Indian China Shop’ (Ostindiska porslinsboden), ‘Grevemühl’s furniture shop’ (Grevemühls möbelbod) and furthermore decorators produced lacquered works in East India style or similar for the growing consumer society. Other tables which demonstrated the family’s high standard of living were a number of writing desks, secretaires, small decorative pedestals and gambling-tables. Two examples of the last mentioned were placed in the Countess’ Drawing-room listed as ‘1 square-shaped gamble-table to fold of walnut tree with green broadcloth within and the other ditto backgammon table of walnut wood lined with green broadcloth, gotten from Stockholm’. In other words, from the Palace, known as the “Petersenska huset” [Petersen’s house] on Kungsholmen in Stockholm, a house owned by the Piper Family since 1692.

Notice: Quotes are translated from Swedish to English. A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography & information about the project, please see Viveka Hansen’s book, 2004 (pp. 11-14 & 38-62).

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd sid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof (Piper Family archive, no D/Ia).

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969, pp. 202-272/embroidery. (English edition: Swedish Handicraft, 1976).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE