ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TAPESTRY WEAVING IN SWEDEN

From 1500 to 1850: with Influences from Flanders, Netherlands and France

Large woven tapestries were used for practical and aesthetic reasons alike. Practically, such textiles helped to keep the cold away from poorly heated buildings. From an aesthetic point of view, movable tapestries replaced earlier frescoes. The tapestries were beautiful and demonstrated the family’s wealth, but they were also used for educational reasons, often including religious themes. During the Renaissance, the Dutch towns were developed into centres of tapestry weaving by the Dukes of Burgundy. Small-scale craftwork soon turned into large-scale manufacturing, and tapestries were exported to royalty and the high nobility all over Europe, which later on inspired other strata of society to produce figure-woven dove-tail tapestries of innumerable designs.

The history of tapestry weaving in Sweden from the 16th century and its development in the court sphere was already recorded by the historian John Böttinger in the 1890s. His documentation revealed that in the 1530s, King Gustav Vasa hired weavers from Flanders to work in the Swedish workshops, and together with Swedish craftsmen they produced tapestries in the royal castles. According to historical information from the museum catalogue card about this well-preserved tapestry, it was woven by Nils Eskilsson in Gustav Vasa’s tapestry weaving workshop in 1554. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NMA.0025679).

The history of tapestry weaving in Sweden from the 16th century and its development in the court sphere was already recorded by the historian John Böttinger in the 1890s. His documentation revealed that in the 1530s, King Gustav Vasa hired weavers from Flanders to work in the Swedish workshops, and together with Swedish craftsmen they produced tapestries in the royal castles. According to historical information from the museum catalogue card about this well-preserved tapestry, it was woven by Nils Eskilsson in Gustav Vasa’s tapestry weaving workshop in 1554. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NMA.0025679).During the second half of the 16th century, the royal workshops continued to make mainly large-sized wall tapestries. Whilst the production of tapestries for the court almost stopped during the following century and first decades of the 18th, at the end of which period it received a boost due to the newly built royal castle in Stockholm. The majority of work now produced was chair covers, probably much influenced by traditions in France, because some of the weavers had worked in the Gobelins factory in Paris. However, such French contacts existed not only in court, the nobility also showed interest in these textiles. An example can be traced to an inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House in southernmost Sweden. The yellow room on the third floor had woven tapestries, listed as: ‘The room was covered by French Gobelin tapestries from Stureforsa, and they had green cloth over the doors’. The notice that the tapestries previously hanged in one of the Piper family’s other homes – ‘Sturefors’ in the county of Östergötland, purchased by Carl Piper already in 1699 – makes it likely that the hangings were ordered around this time from one of the French manufacturers, probably from Beauvais tapestry manufacture, which to a greater extent sold to foreign wealthy costumers.

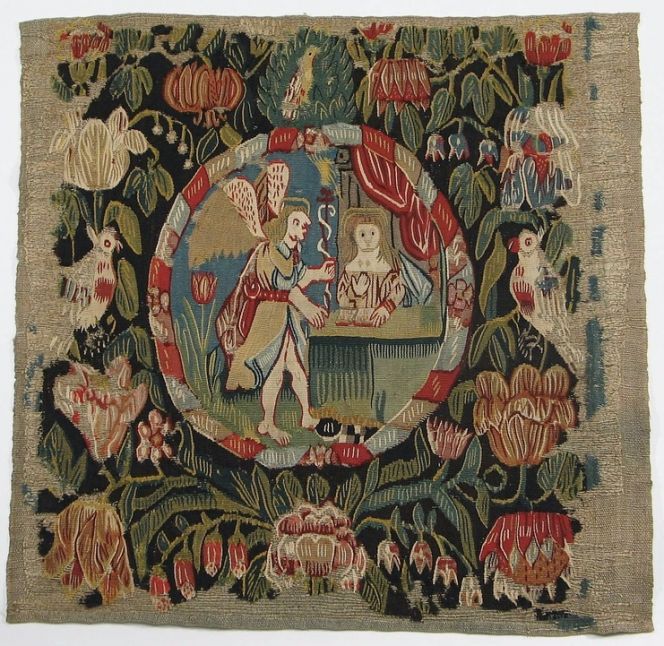

The French tapestry manufacturing which had flourished since centuries back is only looked at briefly in this essay, but on a smaller scale tapestry weaving also spread to the German lands via Holland and Flanders to the towns of Lüneburg, Lübeck, Wismar, Hamburg and Stettin. In these centres, the composition of the pictures were sometimes simplified as well as the size was reduced to a cushion or similar interior textiles. From the 16th century onwards, pictorial weaves of different kinds were also made in Schleswig-Holstein, Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. This tapestry woven cushion cover from the Dutch Republic (Netherlands) dating circa 1650-80, is a representative example of a practical household item with a religious theme – ‘Ester and Ahasuerus’ from the Old Testament. (Collection: V&A, London. no. T.31-1946, from the exhibition ‘Europe 1600-1815’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The French tapestry manufacturing which had flourished since centuries back is only looked at briefly in this essay, but on a smaller scale tapestry weaving also spread to the German lands via Holland and Flanders to the towns of Lüneburg, Lübeck, Wismar, Hamburg and Stettin. In these centres, the composition of the pictures were sometimes simplified as well as the size was reduced to a cushion or similar interior textiles. From the 16th century onwards, pictorial weaves of different kinds were also made in Schleswig-Holstein, Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. This tapestry woven cushion cover from the Dutch Republic (Netherlands) dating circa 1650-80, is a representative example of a practical household item with a religious theme – ‘Ester and Ahasuerus’ from the Old Testament. (Collection: V&A, London. no. T.31-1946, from the exhibition ‘Europe 1600-1815’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. In the making of tapestries, the design, in the form of a sketch is placed behind the warp threads. The tapestry is woven on its side in a high-warp loom, when complete, the linen warp (covered by the weft) runs horizontally. The wefts of wool – sometimes also including silk or metallic threads of gold and silver – follow the rounded forms found in the design, and dove-tailing is used to join two areas of colour, where there would otherwise be a slit. This close-up detail of a large-scale wall tapestry shows the fineness of such skilled work. Just like on the cushion above it was woven in the Dutch Republic (Netherlands), but in this case about one hundred years earlier – circa 1550 – by an unknown manufacturer in wool and silk on a linen warp. The design was the popular ‘verdure with animals’, dominated by green vegetation (faded to blue) together with flowers, mythological creatures and “exotic” animals from other continents (Collection: Design Museum Denmark. no. 9/1972. Exhibition. ‘Creme de la Creme’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

In the making of tapestries, the design, in the form of a sketch is placed behind the warp threads. The tapestry is woven on its side in a high-warp loom, when complete, the linen warp (covered by the weft) runs horizontally. The wefts of wool – sometimes also including silk or metallic threads of gold and silver – follow the rounded forms found in the design, and dove-tailing is used to join two areas of colour, where there would otherwise be a slit. This close-up detail of a large-scale wall tapestry shows the fineness of such skilled work. Just like on the cushion above it was woven in the Dutch Republic (Netherlands), but in this case about one hundred years earlier – circa 1550 – by an unknown manufacturer in wool and silk on a linen warp. The design was the popular ‘verdure with animals’, dominated by green vegetation (faded to blue) together with flowers, mythological creatures and “exotic” animals from other continents (Collection: Design Museum Denmark. no. 9/1972. Exhibition. ‘Creme de la Creme’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Although the wealthiest strata of society in Sweden preferred to import their wall covers during the 17th century, domestic tapestry production did not cease. Instead, it moved from the cities and castle workshops to the countryside, where it took on new forms in the hands of the townspeople, clergy and farmers. The earlier naturalistic scenes with figures found on wall hangings and seat cushion covers were now changed to more stylised and simplified forms with flowers and leaves for the major motifs. Traces of such weaving have been found in several Swedish provinces, above all in the southernmost province of Skåne. The dove-tail tapestry traditions of the bourgeoisie in Malmö are well documented through in-depth research by the late historian Ernst Fischer. Estate inventories show that the technique was already well-known at the beginning of the 16th century and was commonly used in the middle of the century. The inventories suggest that the use of the technique by this section of society did not reach its peak until a hundred years later, around 1650, and continued to be common for another 100 years. Listings of the inhabitants of the city show that women weavers moved from home to home in the early 17th century, weaving tapestries on demand. The same was true for the manor houses of the province, where the tapestry weavers would live while they produced cushions, bench covers and bed covers for the household. However, apart from a few examples that can be dated with certainty to the end of the 17th century, there is virtually nothing left of this early material. The main reason for this seems to be that the area suffered greatly from war, mainly during the 1650 to 1670s, when the province had just become Swedish (part of Denmark before 1658). Another explanation is the frequent occurrence of fires, which often devastated whole villages or parts of towns, together with the obvious wear and tear over such a long period of time.

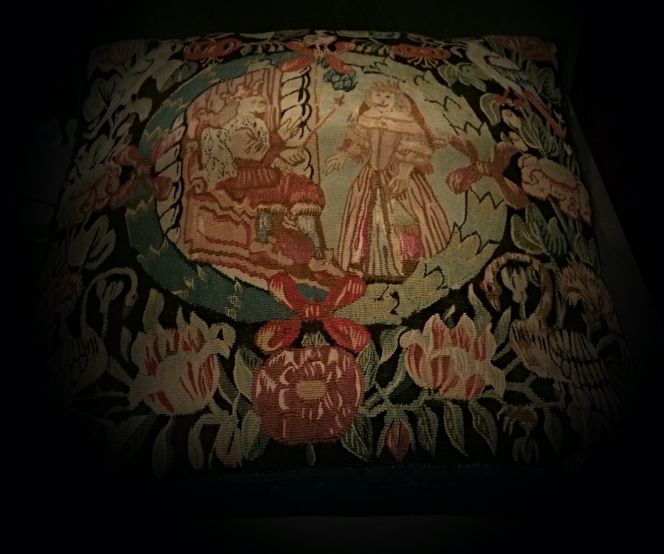

The tapestry or dove-tail tapestry weaving is known in Swedish as “flamskväv” (Flemish weave). It may be noted that the technique is considerably older than woven tapestries from Flanders however, almost identical techniques can be seen on thousands of years old textiles from many parts of the world. Mainly used in the representation of scenes with figures, including animals, people and landscapes but also simple scattered flowers and leaves, often with immense richness in details and nuances. The textiles produced by this technique have been known by many different names in different languages. For instance, this particular mid to late 18th century fragmented cushion cover, indicates with its relative fineness of motif that it probably was woven by a female weaver – wife or daughter – in a clergy household in the province of Småland, homes known for their exceptionally fine works at this time. Contemporary or somewhat later dove-tail tapestries from farming communities in the southernmost province Skåne had equally skilled weavers, but these tapestries were more stylised and somewhat coarser in quality. See images below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0076365A).

The tapestry or dove-tail tapestry weaving is known in Swedish as “flamskväv” (Flemish weave). It may be noted that the technique is considerably older than woven tapestries from Flanders however, almost identical techniques can be seen on thousands of years old textiles from many parts of the world. Mainly used in the representation of scenes with figures, including animals, people and landscapes but also simple scattered flowers and leaves, often with immense richness in details and nuances. The textiles produced by this technique have been known by many different names in different languages. For instance, this particular mid to late 18th century fragmented cushion cover, indicates with its relative fineness of motif that it probably was woven by a female weaver – wife or daughter – in a clergy household in the province of Småland, homes known for their exceptionally fine works at this time. Contemporary or somewhat later dove-tail tapestries from farming communities in the southernmost province Skåne had equally skilled weavers, but these tapestries were more stylised and somewhat coarser in quality. See images below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0076365A). The rich selection of patterns used on these textiles is known from surviving examples from the late 17th century. Occasional references to the patterns can also be found in contemporary estate inventories: for example, in 1677, when Rasmus Olsen owned a seat cushion cover with a ‘shell’ pattern, that is to say, a small palmette-style looking motif. Many of the designs depict biblical scenes; the most common were Esther and Ahasuerus, the Wisdom of Salomon, Samson and the Lion, and Susannah, the Elders. Other typical compositions are very densely drawn forms with a mosaic of flowers, fruits, twigs, leaves and sometimes animals. Another pattern group has figures such as parrots, Annunciation scenes, deer or hunting scenes or clusters of grapes inside a wreath of flowers. Figures depicted inside laurel wreaths, whether densely packed or with spaces in between, seem to be even more diversified since they include cherubs, lambs, unicorns, buildings with towers, parrots and the Tree of Life. Finally, there are rarer patterns of scattered flowers, pomegranates and magnificent swans or flowers inside a frame.

It is evident from the rich supplies of these weaves held by the burghers of Malmö, which mostly can be dated to before 1670 that the south-west part of the province Skåne soon became the centre of dove-tail tapestry weaving in Sweden. After that period and up until 1720, a period of activity took place, when male and female weavers moved out to the countryside. Their works and the works of their apprentices then can be traced to about 1770. After that date, pure handicrafts began in the villages and farms. Most of the extant tapestries in this technique originate from these rural societies where the weavers frequently dated and signed their works, and these inscriptions suggest that the surviving textiles were woven mainly between 1750 and 1850. The earliest mention of a dove-tail tapestry or flamskväv in a farmer’s home can be traced to an estate inventory of 1742, at the death of Ingeborg Persdotter’s husband – though, it is unknown if the tapestry was new at this time. In all events, the number of such tapestries in estate inventories increased during the following decades and reached its peak at the end of the 18th century. This accords well with the dates inscribed on the surviving cushions and covers, which were an important part of the textile dowry prior to a young couple’s wedding. It also seems that the complex art of tapestry weaving became established in certain families and was practised for several generations.

![This depicted loom with its “ongoing weaving” – here seen from the back or weaver’s position – is marked ‘A[nn]o 1830 BOD’. Like the date on the loom suggests, it was in woven by its original owner in 1830 and for some reason never finalised – in Blentarp parish, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. At a time when the dove-tail tapestry weaving ceased in the farming communities of this area. Weaving width circa 60 cm. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0004785).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5-flamsk-664x842.jpg) This depicted loom with its “ongoing weaving” – here seen from the back or weaver’s position – is marked ‘A[nn]o 1830 BOD’. Like the date on the loom suggests, it was in woven by its original owner in 1830 and for some reason never finalised – in Blentarp parish, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. At a time when the dove-tail tapestry weaving ceased in the farming communities of this area. Weaving width circa 60 cm. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0004785).

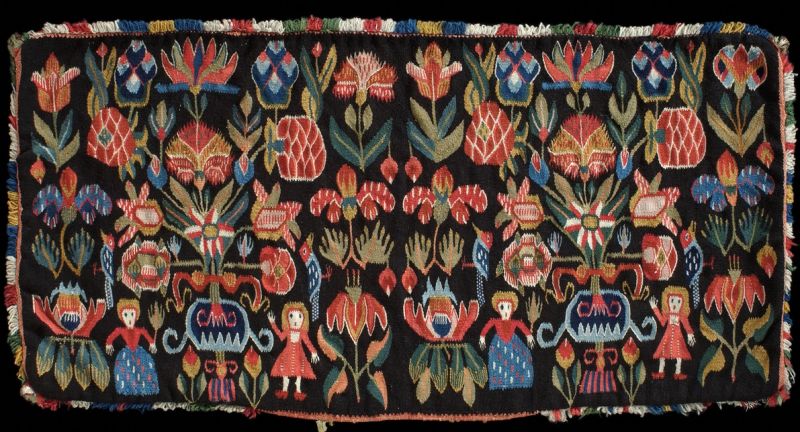

This depicted loom with its “ongoing weaving” – here seen from the back or weaver’s position – is marked ‘A[nn]o 1830 BOD’. Like the date on the loom suggests, it was in woven by its original owner in 1830 and for some reason never finalised – in Blentarp parish, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. At a time when the dove-tail tapestry weaving ceased in the farming communities of this area. Weaving width circa 60 cm. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0004785). This well-preserved cushion woven in a farming community in Torna district in the province of Skåne (Sweden) around year 1800 is typical in its flower design, and contrasting colours carefully woven into the dark brown background. Such dove-tail tapestry with a linen warp and woollen weft, like this example, was in use only for special occasions in the form of carriage cushions when travelling to church or indoors during Christmas, weddings or other festive family moments. The cushion was originally filled with down and feathers for comfortable seating, probably removed in 1873 when the textile was acquired by the Nordic Museum. However, the decorative and protective corner tassels of silk and broadcloth pieces are still extant as well as a woollen fringe and the red plain woven woollen cloth for the back. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0001233).

This well-preserved cushion woven in a farming community in Torna district in the province of Skåne (Sweden) around year 1800 is typical in its flower design, and contrasting colours carefully woven into the dark brown background. Such dove-tail tapestry with a linen warp and woollen weft, like this example, was in use only for special occasions in the form of carriage cushions when travelling to church or indoors during Christmas, weddings or other festive family moments. The cushion was originally filled with down and feathers for comfortable seating, probably removed in 1873 when the textile was acquired by the Nordic Museum. However, the decorative and protective corner tassels of silk and broadcloth pieces are still extant as well as a woollen fringe and the red plain woven woollen cloth for the back. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0001233).The spread of the technique in farming communities seems to have been surprisingly limited, confined to the southwest of the province Skåne and centred on the districts of Torna and Bara, in the vicinity of Lund and the districts south of Malmö, namely Oxie, Skytts and Vemmenhögs. Judging from the patterns used, these two closely situated geographical areas developed a tapestry tradition independent of each other, and it may be assumed that the workshops of the two towns of Lund and Malmö spread the art to their respective vicinity. However, it is not possible with certainty to state why the dove-tail tapestry technique was common only in these two areas. One probable reason is that this type of weaving was very time-consuming, thus limiting it to prosperous farming areas where people had the time for such an occupation. Weavers of this technique would probably also have needed more training and guidance, due to that it was different from all other kinds of weaving in several aspects – when it was made on a vertical upright loom with the pattern placed behind the warp and the shuttle not being in use. Furthermore, the weaver needed a specific artistic ability to keep all the elements of the design in order. Perhaps the occurrence of this particular set of circumstances did not extend beyond southwest of the province Skåne.

Sources:

- Böttinger, John, Svenska statens samling af vävda tapeter, volume 1-4. Historisk och beskrivande förteckning, Stockholm 1895-98.

- Design Museum Denmark (Visit at the exhibition ‘Creme de la Creme’, June 2018).

- Fischer, Ernst, Flamskvävnader i Skåne, Lund 1962.

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art, London 1996. [This essay is partly based on my earlier research of dove-tail tapestries. For a full bibliography, see this book].

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2. London & Whitby 2004 (p. 20).

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive, no D/Ia. The 1758 Inventory).

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. (Four digital images of tapestries. DigitaltMuseum/Creative Commons).

- Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), London, United Kingdom. (Visit at the exhibition ‘Europe 1600-1850', October 2017).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE