ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

TEXTILE APPRENTICESHIPS IN WHITBY

– A Case Study from the 1820s to 1914

Apprenticeships have their roots in the Middle Ages, and until 1814 came under a regulation dating from an English law passed in 1563, which applied to both crafts and trades that came under individual guilds. These guilds had several aims: to maintain norms of quality for various occupations at the same time as ensuring that those working in each trade upheld agreed standards, while the free movement of workers was severely restricted. Thus, young men who wanted to learn a craft either had to leave their family homes to learn their trade wherever apprenticeships were accessible or learned by following in their fathers’ footsteps to learn, for example as tailors, mercers or drapers. However, young men as well as women continued to be named “apprentice” in various printed and handwritten documents up to 1914 within the textile trade of Whitby. This essay will look closer into this tradition, researched from a wide selection of primary sources.

This letter heading for “Lars Kiersta Woollen Draper, Tailor Habit & Pelisse Maker Flower Gate, Whitby”gives a glimpse of the coastal town in the 1820s. The draper described also himself as “Pelisse Maker”, that is to say a woollen draper who handled fur coats or cloaks sewn from fur or with fur edging. Just as for many businesses – predating the local paper as well as censuses – any details about their apprentices over the years are often unknown. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive).

This letter heading for “Lars Kiersta Woollen Draper, Tailor Habit & Pelisse Maker Flower Gate, Whitby”gives a glimpse of the coastal town in the 1820s. The draper described also himself as “Pelisse Maker”, that is to say a woollen draper who handled fur coats or cloaks sewn from fur or with fur edging. Just as for many businesses – predating the local paper as well as censuses – any details about their apprentices over the years are often unknown. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive).The regulated apprenticeship training was extremely thorough and took a considerable number of years to complete – often as many as six or seven – but could be longer or shorter according to the degree of specialisation necessary. Even though the Statute of Artificers was no longer valid after 1814, the strict and timeless regulations within some trades had already been relaxed as long as half a century before this change in the law, or even earlier. This was mainly because the strict rules of the guilds were held to frustrate competition and in effect work against the interests of the craftsmen. With the abolition of these regulations the craftsmen and their apprentices benefited from greater freedom in choosing where and how they could learn and practise their craft. However no sources remain which reveal conditions for textile workers in Whitby before 1814. The surviving historical documents for the town are dated between 1821 and 1914 and deal with apprenticeship conditions for any young man or woman wanting to train for a textile occupation with the most important the censuses, apprenticeship indentures, and announcements in Whitby Gazette. The census returns of 1841 to 1911 are the most all-embracing of these sources, since they give general information about the apprentice’s age and name and also show how many persons were engaged in each particular field of apprenticeship. It has not been possible to find any other directly linked historical documents or objects concerning apprenticeships in Whitby, since parish church registers, for example, give no information about apprenticeship practice, while contemporary local writers like Lionel Charlton and George Young have nothing to say on the subject and there are no local photographs showing apprentices in the textile trades.

The census returns, with few exceptions, mark a strict division between female and male occupations, both with regard to apprentices and other workers in the various textile-related occupations. The 1841 census lists only boys and young men as apprentices at that time in Whitby: 15 in drapery, two as linen weaver’s apprentices, six in sailmaking (each named as learning to be either a sailcloth weaver or simply a weaver) while 28 youths were tailor’s apprentices. From this it seems that their period of training for most who called themselves apprentices that year extended for no more than a few years, when one consider the heavy concentration around 14 and especially 15 years. It is more likely though, that it is simply a coincidence that there were so many practising apprentices of the same age, considering that all the later censuses have a wider age-range. Young women could also be trained, mostly to be dressmakers or milliners, but none are described in this first census as apprentices.

Ten years later in the 1851 census four young women are classified as apprentices, two as dressmakers and one as both dressmaker & milliner, while the fourth is just a milliner. As for the males, there were now more of these apprenticed in drapery than in tailoring, reversing the situation of ten years before. This proved to be a trend that grew stronger over the years, the reason being that men’s clothes were increasingly made elsewhere while sales of such clothes increased in Whitby, necessitating a greater number of practising drapers. The total was now 22 worked in drapery, four specialised in linen & woollen drapery, and 12 tailor’s apprentices. In addition 14 young men were learning to be sailmakers, a number that would decline steadily during the next few decades as sailing-ships grew ever fewer. The age-range is now markedly different from ten years before, with a concentration between 15 and 19 years. This shows a “truer” picture of the usual five- or six-year apprenticeship period.

The 1861 census shows fewer young people now deciding to learn their trade as apprentices. This does not mean that fewer young people were involved in textile activities, but that increasingly they did not choose to describe their period of training as an ‘apprenticeship’. Altogether, 37 persons active with textiles now saw themselves as apprentices, nearly 20 fewer than ten years before. Two 15-year-old girls were respectively a milliner’s apprentice and a milliner & dressmaker’s apprentice. The totals were: 16 in drapery, four specialised in linen & woollen drapery, seven in sailmaking and eight boys and young men as tailors. There were now no longer any 12-year-old apprentices, but otherwise, the age range was comparable with 1851.

Many textile-related businesses were situated in close-by streets, gates and lanes of the old town, here depicted on photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe taken in Sandgate circa 1880s-1890s. Also giving evidence for via repeated censuses, that many apprentices within drapery, tailoring and dressmaking were actively working as well as living in this area. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-41D).

Many textile-related businesses were situated in close-by streets, gates and lanes of the old town, here depicted on photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe taken in Sandgate circa 1880s-1890s. Also giving evidence for via repeated censuses, that many apprentices within drapery, tailoring and dressmaking were actively working as well as living in this area. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-41D).In the 1871 census, most young men were attracted to the drapery business, just as rather more women than previously saw a future for themselves in a thorough learning of dressmaking or millinery. Only two youngsters were now learning sailmaking and three tailoring, while 26 were working as draper’s apprentices and one was specialising in hosiery. Even if 13 and 14-year-olds were still taking up apprenticeships, a slight trend over the decades can be seen for young people in general to wait until they were a little older before starting out on their professional career. In fact, the 1881 census shows the smallest number of apprentices of this whole 70-year period, only 22 persons. The most likely reason for this was the long period of economic depression – in England as in many other countries – that occurred during the 1870s and lasted through the greater part of the 1880s, having a considerable effect on confidence in textile activities in a small town like Whitby. In stagnant periods like this young people were undoubtedly less likely to be able to afford financially to go through a long period of apprenticeship. Those who were still ready to train themselves in textile-related occupations now aimed at just the production and selling of clothes; there were no longer any sailmaking apprentices. As with several of the preceding decades, most young people were involved in drapery (15), while of the rest, two were apprenticed to tailors and milliners, respectively, while three had chosen dressmaking.

Hat labelled ‘Mrs Thornton, Waterloo House Whitby’. The hat can be dated to the 1880s, a time when hats were very small, perched on top of the head and fastened under the chin with a ribbon. This specific example is of extremely elaborate design with velvet, satin, feathers, paste stones, plaited straw and even an “artificial bird”. She worked as a milliner and dressmaker from at least 1879 to 1914 according to advertisements in Whitby Gazette. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, L14). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Hat labelled ‘Mrs Thornton, Waterloo House Whitby’. The hat can be dated to the 1880s, a time when hats were very small, perched on top of the head and fastened under the chin with a ribbon. This specific example is of extremely elaborate design with velvet, satin, feathers, paste stones, plaited straw and even an “artificial bird”. She worked as a milliner and dressmaker from at least 1879 to 1914 according to advertisements in Whitby Gazette. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, L14). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Small advertisements in the Whitby Gazette through which local dressmakers etc looked for apprentices were quite common. In these advertisements it is possible to follow at first hand the opportunities open to young people to learn a profession involving selling clothes in the general context of dressmaking and tailoring from the mid-19th century to 1914. Those most sought after were apprentices in the drapery trade, tailoring, dressmaking, and millinery plus to a lesser extent mantle-making and laundry. At this particular advertisement in 1905, among others the same Mrs Thornton like on the hat made circa 25 year earlier (illustrated above), looked for more than one dressmaker apprentice. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Small advertisements in the Whitby Gazette through which local dressmakers etc looked for apprentices were quite common. In these advertisements it is possible to follow at first hand the opportunities open to young people to learn a profession involving selling clothes in the general context of dressmaking and tailoring from the mid-19th century to 1914. Those most sought after were apprentices in the drapery trade, tailoring, dressmaking, and millinery plus to a lesser extent mantle-making and laundry. At this particular advertisement in 1905, among others the same Mrs Thornton like on the hat made circa 25 year earlier (illustrated above), looked for more than one dressmaker apprentice. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The 1890s witnessed a certain economic recovery nationally and this very likely encouraged a certain optimism in younger people, as can be seen among other things from the greater number of apprentices in the 1891 census. Whitby now had 29 young inhabitants apprenticed to textile-related occupations, and a significant change from earlier decades was that more than 1/3 of them were now young women. Nine of these were active in dressmaking and one in millinery, while the young men included nine as drapers and tailors, and one apprenticed as a cabinet-maker and upholsterer. The 1901 census shows clearly that the optimism of the turn of the century had encouraged many young people to turn to training, since no less than 42 young people were apprenticed in textile-related occupations that year. Young women now accounted for more than 1/3 of the total, 12 in dressmaking and three in millinery, plus one each in art needlework and laundry. The young men’s apprenticeships were as before dominated by the drapery trade, which accounted for 17 apprentices, with one specialising in hosiery and seven as tailors. Starting with this census, no 13-year-old apprentices are recorded any longer.

According to the 1911 census, children who chose this line of work now normally started such learning at 15, principally in domestic service and dressmaking, as apprentices of various kinds and errand boys, etc. A smaller number, mainly from better-off homes, continued at school and were classified as ‘students’, while most children seem to have left school at 13 or 14. This census in fact recorded a smaller number active in textile-related occupations (like textile occupations overall in the area), continuing the same diminishing trend for apprenticeships. Dressmaking attracted the largest number of active apprenticeships with 11 young women followed by seven in drapery and six each as milliners and tailors. Altogether, 30 persons were described as occupied as apprentices in the manufacture and selling of clothes in 1911, including an increased number of young women (17), so that equality had now been achieved in textile-related activities between the genders in Whitby. A significant development compared to the census 70 years earlier, when no female apprentices at all were recorded in 1841.

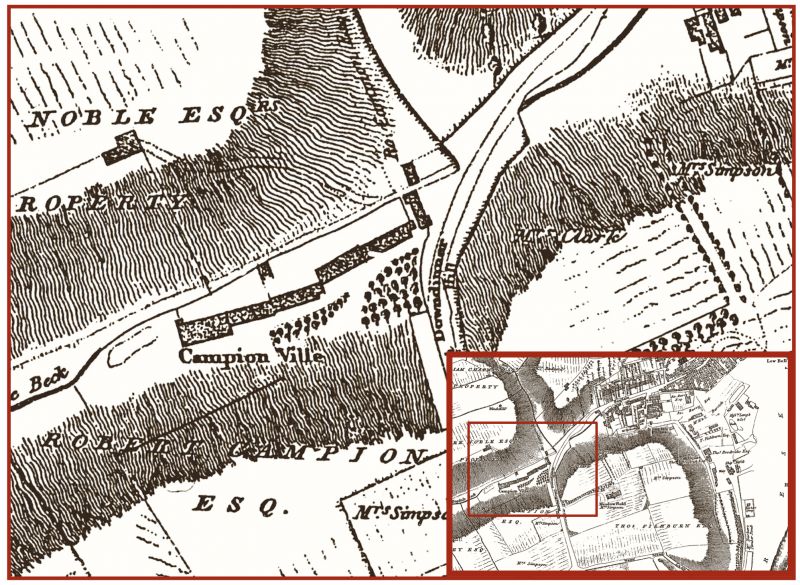

To look back in time once more, via this detailed collage of ‘John Wood’s plan of Whitby and Environs, 1828’. This very detailed plan of the town was the first large-scale professionally surveyed map. Particularly informative is ‘Campion Ville’, where Robert & John Campion were active as Linen and Sail-cloth Manufacturers, as mentioned in Pigot’s 1834 Directory. The 1841 census is also evidence that a significant number of linen weavers, apprentices and their families lived in ‘Campion Ville’. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Map Collection).

To look back in time once more, via this detailed collage of ‘John Wood’s plan of Whitby and Environs, 1828’. This very detailed plan of the town was the first large-scale professionally surveyed map. Particularly informative is ‘Campion Ville’, where Robert & John Campion were active as Linen and Sail-cloth Manufacturers, as mentioned in Pigot’s 1834 Directory. The 1841 census is also evidence that a significant number of linen weavers, apprentices and their families lived in ‘Campion Ville’. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Map Collection).A formal legal agreement – a so-called ‘indenture’ – was an important document for apprentices, as evidence of officially approved proficiency in their particular occupations. Even after obligatory apprenticeship by indenture was abolished in 1814, a certain number of these documents continued to be issued. Three that relate to textile activities in Whitby survive; that are dated between 1821 and 1864. The earliest, from 1821, relates to George Barnett, son of the sail-cloth weaver William Barnett: ‘George Barnett hath of his own free Will, and with the consent of his parents put and bound himself Apprentice to and with the said Robert Campion...’ and the young man promised to ‘faithfully and diligently serve to the utmost of his Power...’ Mr Campion, who owned and ran one of the town’s sail-weaving businesses, undertook to have the young man under his tuition for six years. In addition, he was responsible under the terms of the indenture for paying him 4s a month and a total of £4.0.0 a year during his first and second year, and £5.0.0 during his third and fourth year to rise finally to £6.0.0 during the fifth and sixth years of his apprenticeship. In other words, both parties undertook during these six years to ensure that the young man should, to the best of his ability, learn a craft from the beginning until he had gradually developed into a skilled professional. Another apprenticeship indenture, from 1822, was for Thomas Walker to be trained by the sailmaker Thomas Chilton in Whitby. The terms were similar, except that in this case, the apprenticeship extended over seven years and that Walker was to be paid a weekly wage that would rise during his period of training but amount to a considerably smaller yearly payment. Another historic document is a memorandum of satisfactory completion of this apprenticeship issued seven years later, which shows that the young man had reached a satisfactory level at every stage necessary in the production of sails. The other surviving apprenticeship indenture is dated 1864 and again concerns the training of a sailmaker: William Thomas Gray, who was to be apprenticed for seven years to the sailmaker George Gallilee of Whitby. It is noticeable that his pay, though forty years later than the two other indentures, was no higher than in the 1820s. This was because prices were more or less stable throughout the nineteenth century with virtually no inflation, so that seen from a modern perspective wages were remarkably stable too. This indenture also shows that even as late as the 1860s, when the production of sails was in serious decline, sailmakers continued to train those who carried on their profession according to traditional principles with a solid training lasting seven years.

Sources:

- Charlton, Lionel, The history of Whitby and of Whitby Abbey, York 1779.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 88-94 & 116-119).

- Pigot’s Directory (Yorkshire section) 1834.

- Rodway, Eric, Whitby in 1851, Whitby 1988.

- The National Archive (Census 1911, Whitby. Digital source).

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Including: Whitby Gazette 1855-1914, a letter heading, Plans and Views of Whitby & Apprenticeship indentures 0044/1, 0045/1, 0048/1).

- Whitby Museum, Photographic-, Map- & Costume Collections. Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Including: studies of a wide selection of photographs, plans and clothes with labels).

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1881-1901 microfilm).

- Young, George, A picture of Whitby and its Environs, Whitby 1840.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE