ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILE GOODS AT BAZAARS & MARKETS

– Reflections by 18th Century Travelling Naturalists

Everyday needs and long-lasting traditions in local communities were crucial for marketplaces and all such intertwined commerce. This essay will look into global encounters of diverse societies in urban and rural areas – via in-depth studies of travel journals and correspondence by Carl Linnaeus' seventeen apostles, who travelled to more than 50 countries from 1746 to 1799. In particular, the trade of textile materials and clothing changed hands on markets, bazaars and street stalls in Amsterdam, Stockholm, London and Cairo, along the Silk Routes and in the North American colonies. Most of these naturalists had detailed instructions to follow during such journeys; trade was one of many branches of knowledge to take an interest in. A selection of four artworks and one early photograph may further emphasise the consumption patterns of the time.

![This energetic scene depicted an autumn market at Skeppsbron [The Ship’s Bridge] in Stockholm circa 1750; among many matters, the painting gives a rare insight into selling cloth in the stalls. The trade in Stockholm was substantial regarding domestic and imported fabric qualities. However, none of the seventeen Linnaeus Apostles knowingly made any observations from this particular marketplace. Still, doubtless, they all visited Stockholm at one time or another during their student years in Uppsala, situated just 70 kilometres north of Stockholm. Five of them even lived in the capital, either as children or later in life. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Sweden. No: NMA.0054387. DigitaltMuseum. Oil on canvas by an unknown artist).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1a-hostmarknad-1759-800x439.jpg) This energetic scene depicted an autumn market at Skeppsbron [The Ship’s Bridge] in Stockholm circa 1750; among many matters, the painting gives a rare insight into selling cloth in the stalls. The trade in Stockholm was substantial regarding domestic and imported fabric qualities. However, none of the seventeen Linnaeus Apostles knowingly made any observations from this particular marketplace. Still, doubtless, they all visited Stockholm at one time or another during their student years in Uppsala, situated just 70 kilometres north of Stockholm. Five of them even lived in the capital, either as children or later in life. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Sweden. No: NMA.0054387. DigitaltMuseum. Oil on canvas by an unknown artist).

This energetic scene depicted an autumn market at Skeppsbron [The Ship’s Bridge] in Stockholm circa 1750; among many matters, the painting gives a rare insight into selling cloth in the stalls. The trade in Stockholm was substantial regarding domestic and imported fabric qualities. However, none of the seventeen Linnaeus Apostles knowingly made any observations from this particular marketplace. Still, doubtless, they all visited Stockholm at one time or another during their student years in Uppsala, situated just 70 kilometres north of Stockholm. Five of them even lived in the capital, either as children or later in life. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Sweden. No: NMA.0054387. DigitaltMuseum. Oil on canvas by an unknown artist).The apostle Daniel Rolander (1723-1793) was chosen by the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and other men of science to make a journey to Suriname in South America, with the aim to collect and catalogue natural specimens. Rolander departed in October 1754; he travelled via Ystad, through the northernmost part of Germany, towards Amsterdam, whence the ship set sail on 12 April and arrived in South America on 20 June 1755. Illness was his constant companion from the very beginning; he was bedridden already in Amsterdam on several occasions, but there was also time for observations about the busy trade of the city. On 5 January, more than four months prior to his Atlantic sailing, the following thoughts on selling and buying in the streets were noted in his travel journal. Wealth, as well as deepest poverty, were on display:

- ‘The commerce is very busy here. It supplies every citizen with food and clothing. Everywhere you turn your eyes, you see tradesmen. There is hardly any house without a mercantile tavern. Every street and corner of the city is full of merchandise. Here is an enormous amount of precious things, ordinary things, and things which are so cheap that elsewhere they are usually thrown away as totally useless. For no garment is so torn and frayed, no flap of a garment so oft mended, no linen so worn out and sordid, no metal object so destroyed, frail and rust-eaten, and finally no kind of food or drink so worthless, that they cannot be put up for sale in someplace. In addition to the taverns and the fixed mercantile places, there are ambulant tradesmen who are Jews. They move around on every street in the city and with stentorian voices shout out their goods for sale and ask to mend other things. Here and there on the streets, you can see crowds of young sailors walking around, offering to buyers various merchandise imported on their ships.’

Oil on canvas by the London artist William Hogarth (1697-1764) or in the style of this famous painter. Judging by the fine lady’s sack-back silk gown, this study of a market stall that sold hares and game birds placed on a linen fabric, etc., dates from circa 1750. Just around the time when the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) visited London. The depicted area also appears to be very prosperous – visible via grand architecture, well-to-do citizens accompanied by servants carrying the purchases home in a basket, a washerwoman to deliver the laundry, grapes for sale, which must have been grown in greenhouses as well as the overall neat impression of everyday life. (Private Art Collection, Denmark). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

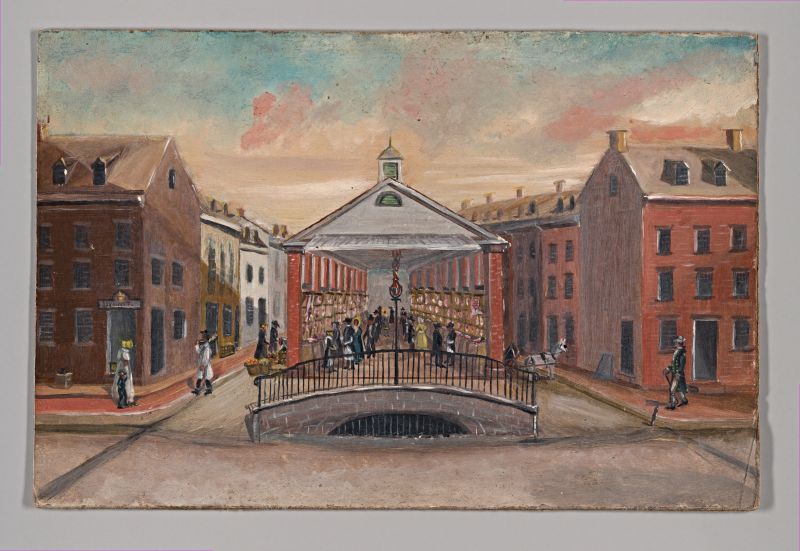

Oil on canvas by the London artist William Hogarth (1697-1764) or in the style of this famous painter. Judging by the fine lady’s sack-back silk gown, this study of a market stall that sold hares and game birds placed on a linen fabric, etc., dates from circa 1750. Just around the time when the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) visited London. The depicted area also appears to be very prosperous – visible via grand architecture, well-to-do citizens accompanied by servants carrying the purchases home in a basket, a washerwoman to deliver the laundry, grapes for sale, which must have been grown in greenhouses as well as the overall neat impression of everyday life. (Private Art Collection, Denmark). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Another geographical link to the former Carl Linnaeus student Pehr Kalm is the Old Fly market in New York as it appeared in 1808, according to a note on the back of this painting, as well as evident via the style of clothing worn by the depicted individuals. This particular market and its surrounding quarters were the same as Kalm mentioned in his journal, experienced during a visit to New York in 1749, which is briefly discussed below linked to the trade of cloth in the area. |Oil on slate paper by William P. Chappel (1801–78), painted in the 1870s. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art. No: 54.90.492).

Another geographical link to the former Carl Linnaeus student Pehr Kalm is the Old Fly market in New York as it appeared in 1808, according to a note on the back of this painting, as well as evident via the style of clothing worn by the depicted individuals. This particular market and its surrounding quarters were the same as Kalm mentioned in his journal, experienced during a visit to New York in 1749, which is briefly discussed below linked to the trade of cloth in the area. |Oil on slate paper by William P. Chappel (1801–78), painted in the 1870s. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art. No: 54.90.492).Pehr Kalm’s observation of the inhabitants of European descent in the North American colonies preferring to buy imported fabrics from England is reinforced by a contemporary advertisement in the New York Gazette on 13 November 1749. The advert indicates that several different qualities of woollen and linen fabrics were shipped from England and Ireland to the port of New York. The example is an advertisement for ‘Yorkshire Broad Cloths...’ which had been loaded at Bristol and sold after reaching America at ‘Francis Lewis’ near the Fly Market’. Kalm described in his journal the intensive trading of New York; whether he ever visited the areas around the Fly Market cannot be verified with certainty, but it is likely as that market was one of the most critical locations for commerce in the city. The essential preconditions for the textile trade depended not only on individual wishes or a lack of the raw material wool but were far more complicated than that, as the import of fabrics was governed by several Navigation Acts from the 17th century, resulting in British fabrics virtually dominating the market. That piece of legislation is, for instance, noted as follows in current research: ‘Subsequent British trade regulations included the 1660 Navigation Act, which required all colonial trade to be on English ships…’ (Peck) with additional acts in 1663, 1696 and 1699, which further strengthened the position of British fabrics in the North American colonies.

The central part of Kalm’s interest in markets relates to food and drink or live animals or is mentioned as ‘provisions’ only in his journal. Such regularly kept markets occurred once or twice a week in various towns and cities in the North American colonies along the east coast. On 2 November 1748, for example: ‘The country people come to market in New York, twice a week much in the same manner, as they do at Philadelphia; with this difference, that the markets are here kept in several places.’ Brief observations of markets were also included in other journals written by these naturalists on long-distance voyages, in particular by;

- Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) in Cadix and Canton [today Guangzhou] | 1751

- Daniel Solander (1733-1782) in Rio de Janerio |1768

- Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) in the Cape of Good Hope area, in Batavia (Djakarta) and Nagasaki | 1772-1777

- Göran Rothman (1739-1778) in Copenhagen and Tripoli | 1773-1774

- Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) in the Cape area, at the Society Islands and New Caledonia | 1773-1776

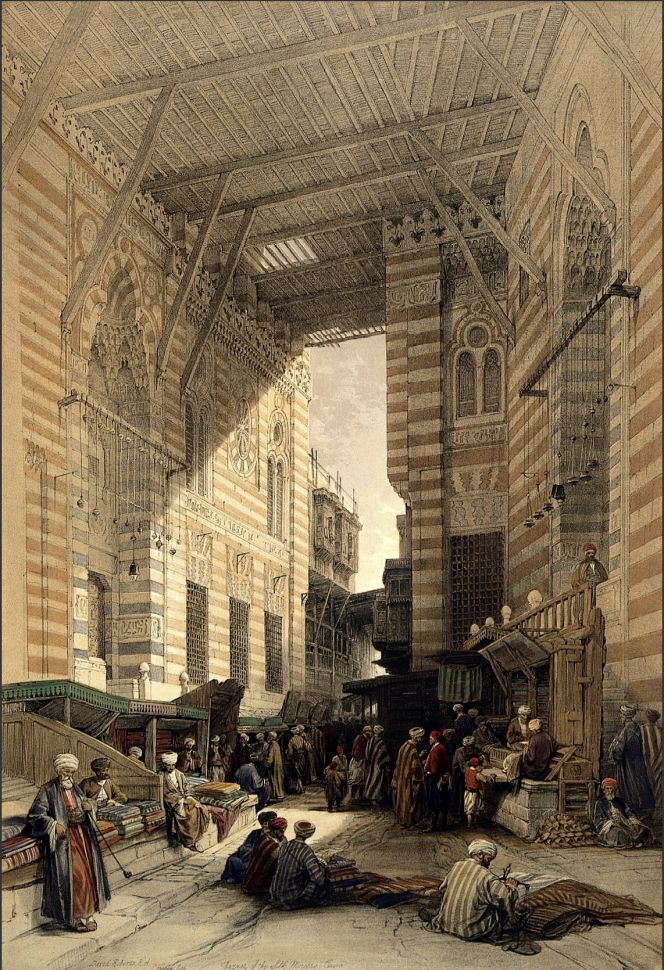

The naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) may not have mentioned the Sultan al-Ghuri complex by name, which was situated in the mediaeval town centre, but he indeed spent time in Old Cairo in the autumn of 1750, studying its architecture, people’s way of living, a mosque, commerce etc. This beautiful illustration was made nearly a century later (1848) when the roofed area functioned like a silk market. The buildings in that complex, comprising, among other things, a mosque, minaret, and mausoleum, the sections reserved for commerce had existed for over 200 years by the time Hasselquist visited Cairo, so he must have moved about in those commercial quarters. His records concentrated mainly on the extent of the trade in woollen cloth in the town, but he did not ignore the importance of raw silk and silk fabrics for The Mecca Caravan. |Colour Lithograph by David Roberts – ‘Bazaar of the Silk Mercers in Cairo’. (Courtesy: Wellcome Trust, images L0021542).

The naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) may not have mentioned the Sultan al-Ghuri complex by name, which was situated in the mediaeval town centre, but he indeed spent time in Old Cairo in the autumn of 1750, studying its architecture, people’s way of living, a mosque, commerce etc. This beautiful illustration was made nearly a century later (1848) when the roofed area functioned like a silk market. The buildings in that complex, comprising, among other things, a mosque, minaret, and mausoleum, the sections reserved for commerce had existed for over 200 years by the time Hasselquist visited Cairo, so he must have moved about in those commercial quarters. His records concentrated mainly on the extent of the trade in woollen cloth in the town, but he did not ignore the importance of raw silk and silk fabrics for The Mecca Caravan. |Colour Lithograph by David Roberts – ‘Bazaar of the Silk Mercers in Cairo’. (Courtesy: Wellcome Trust, images L0021542).![Textile merchant in Samarkand on the Silk Route circa 1905-15 – a prosperous trading city for more than a thousand years at this time. This early colour photograph gives a unique and informative comparison to trading in all sorts of desired delicate fabrics, probably similar to the qualities originating from the wide-stretching caravan routes mentioned in Johan Peter Falck’s (1732-1774) extensive journal. (Courtesy: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, reproduction number, LC-P87- 8001A [P&P] LOT 10338).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5a-samarkand-800x734.jpg) Textile merchant in Samarkand on the Silk Route circa 1905-15 – a prosperous trading city for more than a thousand years at this time. This early colour photograph gives a unique and informative comparison to trading in all sorts of desired delicate fabrics, probably similar to the qualities originating from the wide-stretching caravan routes mentioned in Johan Peter Falck’s (1732-1774) extensive journal. (Courtesy: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, reproduction number, LC-P87- 8001A [P&P] LOT 10338).

Textile merchant in Samarkand on the Silk Route circa 1905-15 – a prosperous trading city for more than a thousand years at this time. This early colour photograph gives a unique and informative comparison to trading in all sorts of desired delicate fabrics, probably similar to the qualities originating from the wide-stretching caravan routes mentioned in Johan Peter Falck’s (1732-1774) extensive journal. (Courtesy: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, reproduction number, LC-P87- 8001A [P&P] LOT 10338).The former Linnaeus student Johan Peter Falck arrived in St. Petersburg in 1763, where he first worked at the Cabinet of Natural History and later at the Botanical Garden of the Imperial College of Medicine. In 1768, he got the opportunity to lead one of the Imperial Academy of Sciences’ natural history expeditions and accepted the offer. Falck was assisted by several students, a taxidermist, a huntsman, an artist and from July 1770, the botanist Johan Gottlieb Georgi (1729-1802), together with other travelling naturalists in the complex network of the Imperial expeditions. Falck recorded everything from his journey meticulously: types of landscape, provinces, villages, buildings, water, types of stone and soil, botany, zoology, nationalities, languages, bazaars, traditional clothing, etc. The result was a comprehensive travel journal, which was kept over a five-year journey. His descriptions of bazaars or markets in visited towns along the route give evidence of commerce that sold various goods. In conclusion, three examples will highlight the multitude of wares for sale across the vast areas of land in present-day Russia and Kazakhstan:

- In Kazan: ‘The town proper, or upper town, is higher up the ridge between the rivers and open on the land side. Its streets are covered in places with wooden planks and nowhere paved. It has two markets, the bigger with a bazaar (gostinyi dvor), a massive structure, the other shops being of wood, insubstantial and terraced in rows. 57 of them were for travelling merchants selling their wares cheap, 9 cloth shops, 28 for Siberian and Chinese goods, 36 for cloth for clothing, 16 for silver and 17 for iron goods, etc. There were 776 in all, with another 86 stalls or shops on the little market.’

- The region around Tyumen: ’The countrywomen here are no less industrious. Apart from the usual housework, they spin flax, hemp and wool, weave linen and coarse cloth, knit stockings and gloves, make ribbons, lace and lace-trimmings, embroider bonnets with gold and silver, weave silk girdles (kushaki) and carpets, make felt blankets and horse-blankets, etc., which merchants buy from them and take to the towns and markets.’

- The Kirghiz and their domestic economy of sheep: ‘The wool is short, coarse and thick, and mainly used to make horse blankets, which are so indispensable to them. Perhaps it is coarser than it otherwise would be because the animals are always out in the open air. They shear the sheep twice a year. Their shears are 1⁄2 arshin long. Gives 2 pounds of wool each time, which they do not grade. They make their winter furs from the skins and also take the finished product to market in Orenburg. The scale of their sheep-breeding can be assessed from the fact that in Orenburg, they bartered 140,000 sheep in 1769 and 138,000 in 1770, excluding the lambs and the countless sheepskins and lambskins. In some years, the numbers have been even higher.’

Sources:

- Falck, Johan Peter, Beytraege zur topographischen Kenntniss des Russischen Reichs…vol. 1-3, St Petersburg 1785-1786.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Two: Johan Peter Falck’s journal. Vol. Three: Pehr Kalm’s and Daniel Rolander’s journals. Vol. Four: Göran Rothman’s journal. Vol. Seven: Pehr Osbeck’s journal. Daniel Solander’s correspondence).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 37-38 & 185).

- Hasselquist, Fredrik, Voyages and Travels in the Levant. In the years 1749, 50, 51, 52, London 1766.

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Peck, Amelia, ed., Interwoven Globe – The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, New York 2013 (Quote: p. 324).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE