ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

TEXTILE MANUFACTURING IN BRITAIN

– a Case Study from 1700 to 1850

The pre-industrialisation in urban, rural and domestic areas may be seen from the perspectives of textile manufacturers as well as the many spinners, weavers and connected occupations in workplaces at home and in factories. The rising consumption and standard of living for “the middling sort” in the 18th century – were two of several factors that appear to have contributed to the increasing speed of the Industrial Revolution. This essay will foremost give a glimpse into the interdependence between dangers and long hours for the factory workers, child labour and young women in the workforce, philanthropic and social aims, small-scale manufactures, power-driven looms and the long-established woollen cloth trade.

-900x499.jpg) One of several steam-powered cotton mills in Ancoats, Manchester, conveniently situated by the canal for transport of goods. McConnel & Company's mills, about 1820. Drawn in 1913 from an old water-colour drawing of the period (Wikimedia Commons).

One of several steam-powered cotton mills in Ancoats, Manchester, conveniently situated by the canal for transport of goods. McConnel & Company's mills, about 1820. Drawn in 1913 from an old water-colour drawing of the period (Wikimedia Commons).Textile industries that steadily increased their production and brought their owners large profits could never have been so successful without the help of low-paid workers working unreasonably long hours, in addition to ample access to raw materials. So long as spinning and weaving were mostly done in the home, men and women usually kept to a strict division of labour. Men did the weaving, but it was usually women, children and the elderly who attended to the preliminary work from raw material to spun yarn. With the introduction of larger manufactures and industrial development this tradition was relaxed, and it became possible for women too to look after some of the looms. The male workforce was now joined by mainly young and unmarried women, together with children and married women. Work opportunities tripled in number between 1750 and 1800, and by about 1820 more than 50% of the textile workers were women. This line of occupation was seen as a viable way of making a living despite low pay, a working day of 12 to 14 hours and many unhealthy or even outright dangerous places of work. Since the workers required no special qualifications, it was entirely possible for children to do the same work as women, and indeed, many actually did so in the Yorkshire textile industries and other places. Even if the factory employees’ day involved such hard work, young people must have experienced advantages compared with the other possibilities available to them. Many moved into the towns and became economically independent of their parents, at the same time avoiding the loneliness that often afflicted domestic servants.

-664x790.jpg) Portrait of Robert Owen (1771-1858), ca 1820s-1830s by William Henry Brooke. (Courtesy of: National Portrait Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons).

Portrait of Robert Owen (1771-1858), ca 1820s-1830s by William Henry Brooke. (Courtesy of: National Portrait Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons).Nor were all industries appalling places to work since some owners took good care of their workers and offered their children education, etc. Within the textile industry, the most famous social experiment was that of Robert Owen (portrayed above) in New Lanark, where he aimed to provide an ideal society for nearly 2,000 textile workers. He was not alone in his ideas, since there also existed a factory movement with the purpose of improving conditions in the workplace for factory workers. A world that Owen was already familiar with as a youth when building spinning machines, and he later worked as a cotton spinner himself, becoming, at the age of 21, a mill manager in Manchester. He bought New Lanark in 1799 as an already established cotton mill with social aims, since its previous proprietor had tried to make life more tolerable for small children by offering them schooling and shorter working hours at the mill. Owen introduced further improvements, including infant childcare, a system of education for children and a cooperative trading movement for his employees. His philanthropic ideas commanded deep respect among the workers, and despite the cost of his reforms, they were nonetheless a commercial success.

England already had a considerable number of small textile-related businesses in various parts of the country as early as 1700; for example, in Whitby, this industry was most involved with sail-making. While London specialised in silk-weaving and Lancashire developed the manufacture of cotton while, the important production of woollen goods had several centres, each with its own speciality. The most extensive and important areas for wool were the West Riding of Yorkshire in particular, but also East Anglia and the West Country. During this period before the Industrial Revolution, cottage industries were universal, so carders, spinners, weavers, and others either worked in their own homes or for an employer, hoping to progress to selling their cloth themselves. After the mid-18th century cloth began to be manufactured semi-industrially, with some stages still produced in a home environment while other stages came to be done by small manufacturers, though increasingly from the 1780s, all stages of production, from the preparation of the raw material through spinning and weaving were conducted in special industrial premises with many workers under the same roof. Yet in many places where textiles were produced during the second half of the 18th century, working at home co-existed for long periods with industrial production.

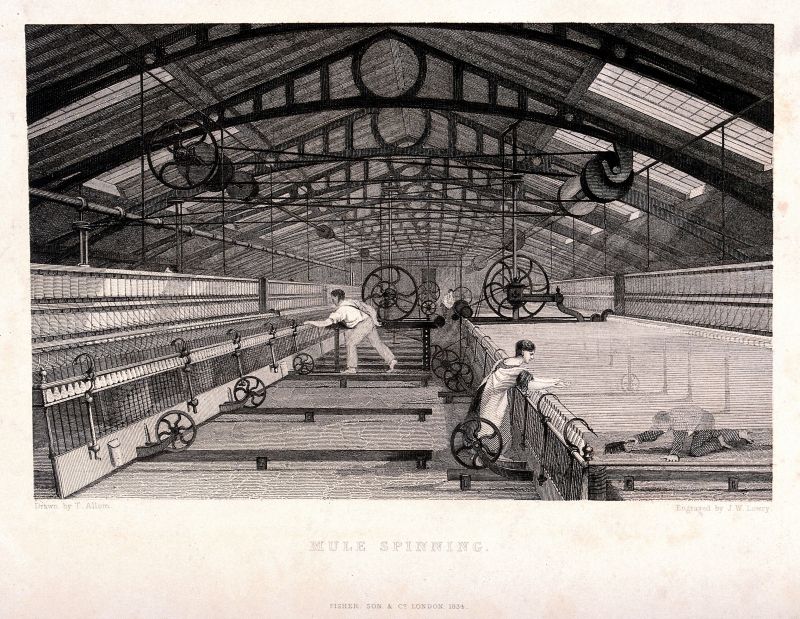

Mule Spinning – From: ‘History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain’ in 1835 by Edward Baines. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. L0011292).

Mule Spinning – From: ‘History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain’ in 1835 by Edward Baines. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. L0011292).Spinning was a particularly slow stage in the process that occupied many women, including children and the elderly, so long as only one thread at a time could be spun. With the help of spinning-machines, and especially after the invention of the ‘Spinning Jenny’ in 1764, it became possible for this stage in the production of cloth to keep pace with power-driven looms, first introduced at almost the same time. The development of industrialisation was, in general, complex and can therefore be seen from many points of view as a change occurring gradually over many decades.

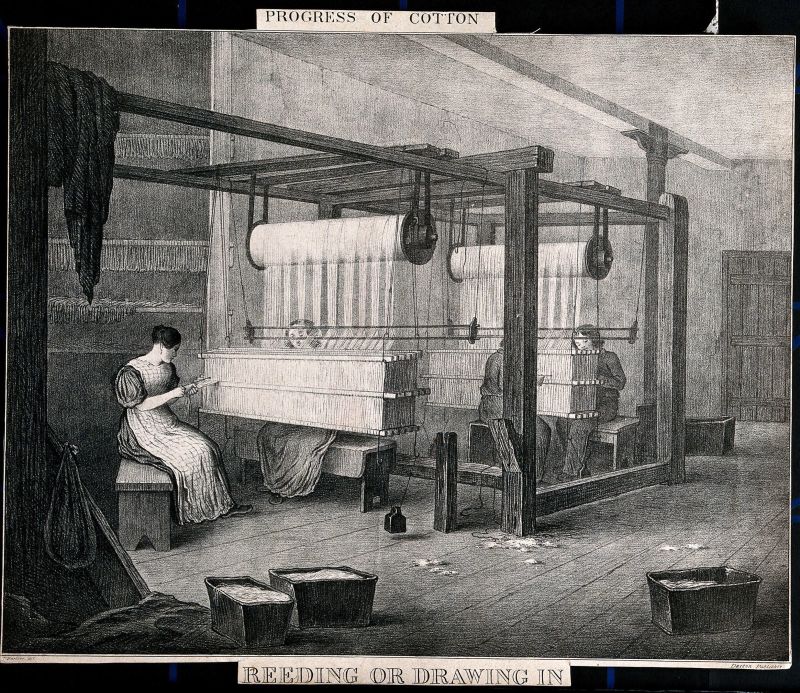

Women and children working at large cotton looms. It may also be reflected that illustrations of this kind left out the dirt and unhealthy working conditions in the textile industry. This image almost gives a calm and peaceful atmosphere of the everyday work of reeding the thousands of warp threads through each and every heddle. 19th century Lithograph after Barfoot. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0039852).

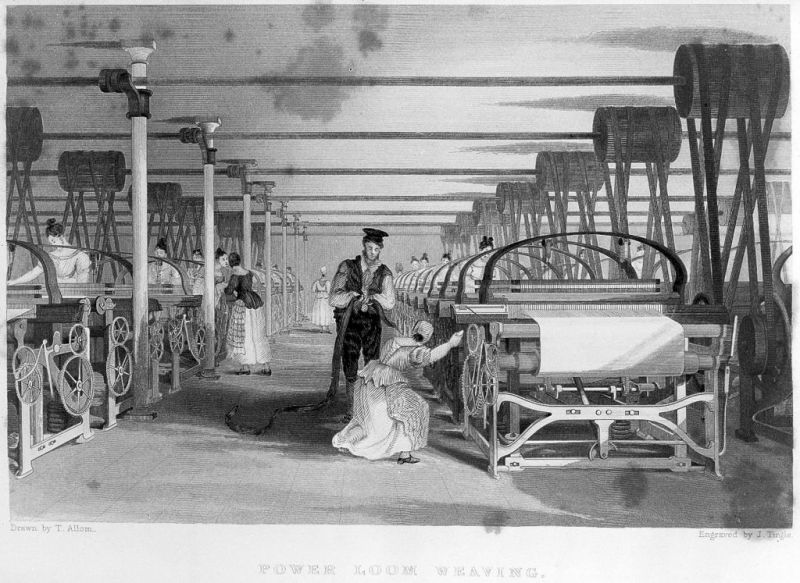

Women and children working at large cotton looms. It may also be reflected that illustrations of this kind left out the dirt and unhealthy working conditions in the textile industry. This image almost gives a calm and peaceful atmosphere of the everyday work of reeding the thousands of warp threads through each and every heddle. 19th century Lithograph after Barfoot. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0039852). Power Loom Weaving – From: ‘History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain’ in 1835 by Edward Baines. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London no. L0011293).

Power Loom Weaving – From: ‘History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain’ in 1835 by Edward Baines. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London no. L0011293).Power-driven machinery, increased trade and a significant increase in population were the main factors in making this change possible as far as textiles were concerned. Just as the woollen cloth trade was profitable for merchants for several hundreds of years before the Industrial Revolution, the new factory system provided even greater opportunities for handsome profits. Yorkshire, with Leeds, Bradford, Wakefield, Halifax and Huddersfield as the principal centres of this constantly growing production, was estimated to account for one-third of the value of the British wool trade. The small coastal town of Whitby lay outside this area, but it is easy to believe that a considerable quantity of the wool bought for the needs of the town came from West Yorkshire. Ever since the Middle Ages, much of the cloth trade had passed through Merchants’ Halls, and so it continued during the 18th century. One such place was Merchant Adventurer’s Hall in York where, among the many much-coveted traded goods, wool products formed a significant part. The wool industry continued to dominate in Yorkshire after 1780, and the rate of production continued to increase in the 19th century. The weaving of linen expanded just as strongly during 1770-1850 but then diminished in importance, while silk weaving always had a more limited role in the area. During the 1780s the weaving of cotton cloth was introduced in Yorkshire, considerably increasing in the 1830s and remaining during the rest of the century the second most important branch of weaving in the county.

Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. First and foremost, it is based on the research linked to ‘Textile Occupations and Trades from a Wider Perspective’ pp. 55-59, published in the monograph by Viveka Hansen, 2015. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see this book.

Sources:

- Armley Mills – Leeds Industrial Museum, United Kingdom (Visit/studies of looms and other textile equipment, 2010).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015.

- Merchant Adventurers’ Hall, York, United Kingdom. (Visit to a Merchants’ Hall, 2012).

- The Open University, Robert Owen and New Lanark (Open Learn: accessed 2010).

- Wellcome Library (Information on catalogue cards).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE