ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILE MANUFACTURING IN INDIA 1778

– Reflections by the Botanist and Physician Johann Gerhard König

Detailed information about the manufacturing of cotton, printing, and painting on cloth, trade with handkerchiefs, and the use of various carpets on the Coromandel coast was part of a European traveller’s diary in 1778. Johann Gerhard König (1728-1785) was born in Livland. At fifty, he had reached an unusually mature age for his time to make a natural history voyage from India to present-day Thailand and Malaysia. Earlier in life, he had been a private student of Carl Linnaeus in 1757, lived in Denmark from 1759 to 1767 and during twelve years from 1773 – a period also including this journey – he acted as a royal botanical collector on a Danish trade mission, closely situated to the British East India Company post in Tranquebar [Tharangambadi]. After König’s death in 1785 at this place in India, his journal and other papers were bequeathed to Sir Joseph Banks. This case study will focus on his informative textile observations made on the outward journey from Madras [Chennai] in August 1778.

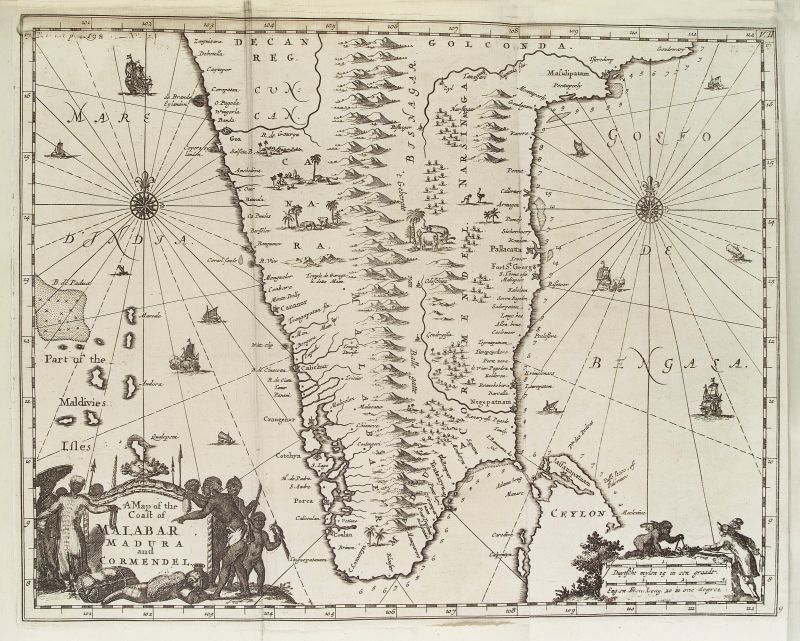

König’s textile observations were made along the coast around Fort St. George, clearly marked on the East Coast of India on this somewhat earlier map. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, 17811/D Vol. 1. In; Churchill, Awnsham, A collection of voyages and travels…1744-1746 3rd ed.).

König’s textile observations were made along the coast around Fort St. George, clearly marked on the East Coast of India on this somewhat earlier map. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, 17811/D Vol. 1. In; Churchill, Awnsham, A collection of voyages and travels…1744-1746 3rd ed.).His main aim with the journey was botanising and describing plants, insects, birds and shells, which is reflected in the quite extensive journal. Still, during the first two weeks of the circa one-and-a-half-year-long voyage, the ship anchored along the coast close to Madras [Chennai] on several occasions. In this area, he made detailed observations of fine kinds of cotton, the complex dyeing/painting process of such cotton and a few mentions of other used and traded textiles in the area. The East India Companies of several European countries were part of his discussion, too. According to the publisher in 1894, the handwritten journal (1778-79) was written in a mix of German and Danish, in a hardly legible hand.

It may also be noticed that König had quite a long-term correspondence with his former teacher Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), but mainly concerning botany and other natural history matters. These letters, dating from 1763 to 1777, are preserved at the Linnean Society of London. However, the period of this particular journey post-date these letters, due to that Linnaeus died in January 1778, before König’s travel journal started. His correspondence from Tranquebar was taken up once more after his journey, in the years 1780-82, but by now to his former teacher’s son – Carl Linnaeus the Younger (1741-1783).

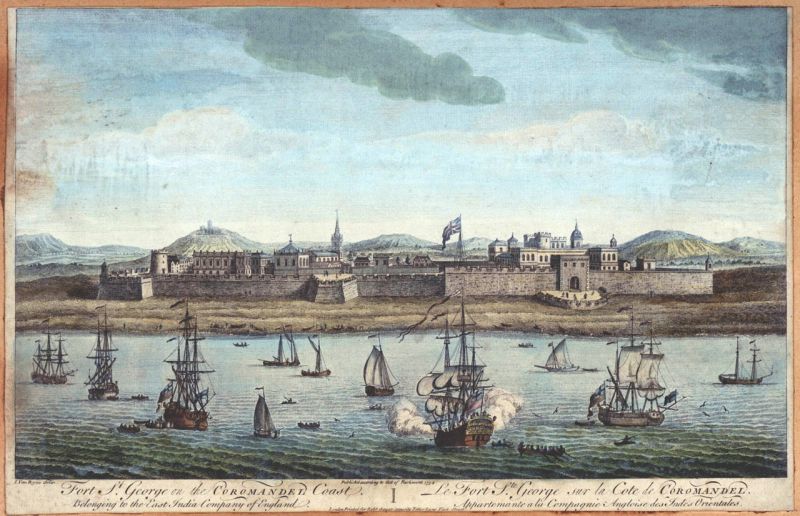

View of Fort St. George in Madras (Chennai) along the Coromandel coast of India in 1754, by Jan Van Ryne (1712-60) – in an area where several European East India Companies at the time of König’s stay in the area had or earlier have had long-term trading posts. (Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Wikimedia Commons).

View of Fort St. George in Madras (Chennai) along the Coromandel coast of India in 1754, by Jan Van Ryne (1712-60) – in an area where several European East India Companies at the time of König’s stay in the area had or earlier have had long-term trading posts. (Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Wikimedia Commons).Some quotes from the initial weeks of König’s “Journal of a voyage from India to Siam [Thailand] and Malacca [city in Malaysia] in 1778-1779” will give informative perspectives about fine textiles, produced and traded along the Coromandel Coast. But also a glimpse into the lucrative positions and changing powers of various East India Companies in the area and their connection to traders from the Asian regions and local inhabitants alike.

The diary commences when the ship Bristol sailed from Madras [Chennai] on 8 August 1778; four days later, at a stopover along the coast König observed the handkerchief trade and uses of other types of pieces of cotton:

- ‘Half a German mile from the town towards the North, one finds first some gardens and villas of the English living out here, and further on the big village, where really all the manufacturers live. The factory productions insist on a striped or flowered kind of cotton. The red Indian pocket handkerchiefs are of pink colour but are just as durable; and many things not actually manufactured here, are brought hither from distant parts of the country and offered for sale. There is also another kind of cotton material manufactured here, it is dyed pompadour, wears well, and is at this moment a very fashionable dress material at Madras’ (12 August).

Even if not mentioned by König, these processes included some initial stages before the cotton was spun and woven into the fabric of various qualities. ‘Bowing cotton’ in India – a technique also used in the 18th century – that is to say, preparation of the fibres or carding. The man in the picture used a large bow to entangle the fibres, whilst the woman makes the fluffy cotton into equal-sized rolls, so in the next stage, the fibre could be spun into fine cotton thread. | By an unknown Indian artist, dating circa 1800-1899. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, no. 576236i, watercolour with pencil and pen).

Even if not mentioned by König, these processes included some initial stages before the cotton was spun and woven into the fabric of various qualities. ‘Bowing cotton’ in India – a technique also used in the 18th century – that is to say, preparation of the fibres or carding. The man in the picture used a large bow to entangle the fibres, whilst the woman makes the fluffy cotton into equal-sized rolls, so in the next stage, the fibre could be spun into fine cotton thread. | By an unknown Indian artist, dating circa 1800-1899. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, no. 576236i, watercolour with pencil and pen).On 16 August, at another stop along the coast, König mentioned the manufacturing and trade of painted cotton as well as woollen carpets – of luxurious and inexpensive sorts, desired by Europeans and Indian inhabitants alike:

- ‘I visited the manufactories of the cotton made here, they are not so beautiful as those from Madras, the colours are not as vivid, but there is very little better material manufactured here.’ Continued with: ‘Many painted articles and much fine linen is brought hither for English society and trade in general. Amongst the articles principals manufactured here, are the Persian carpets, which are used by the Indian grandees to sit upon; these carpets are mostly manufactured in a village called Elluhr, where the English have a fortress, and which is situated at two days journey from Massulipatam. The Europeans have some of these carpets woven here, as large as their largest rooms. They look like a sort of velvet, as regards the way of weaving. The threads that form the chain are cotton, but the fluffy part consists of woven wool, which is taken from some sheep, intermediate between the Indian goats and ordinary sheep. Their hair is rather woolly but very short and stiff to the touch, but when this wool is washed, it has a peculiar gloss, and can be dyed in beautiful rich colours… These carpets are very cheap here, though they pass into the hands of the Armenians.’

Close-up detail of a palampore or bedcover, dated to 1750s-70s. This is a good comparable example to König’s observations above of the very finely hand-painted cotton along the Coromandel coast. This product was very much sought after as luxury goods by the European traders. The secret of its popularity was not only the beautiful motifs but, in particular, the advanced painted resist and mordant dyed technique, unknown in a wider geographical area, which included qualities such as being very durable and light resistant over time. A most desired quality for bedcovers, curtains or wall hangings in wealthy European homes. The admiration for these textile objects in the 18th century is foremost evident today via the substantial number of such extant bedcovers kept in museum collections in Europe and elsewhere. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0114739. DigitaltMuseum).

Close-up detail of a palampore or bedcover, dated to 1750s-70s. This is a good comparable example to König’s observations above of the very finely hand-painted cotton along the Coromandel coast. This product was very much sought after as luxury goods by the European traders. The secret of its popularity was not only the beautiful motifs but, in particular, the advanced painted resist and mordant dyed technique, unknown in a wider geographical area, which included qualities such as being very durable and light resistant over time. A most desired quality for bedcovers, curtains or wall hangings in wealthy European homes. The admiration for these textile objects in the 18th century is foremost evident today via the substantial number of such extant bedcovers kept in museum collections in Europe and elsewhere. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0114739. DigitaltMuseum).Whilst the traveller, on 19 August, reflected on the changing conditions and existence over time for the European East India Companies in the area:

- ‘Madepolam [Narsapur] is a big place, having manufactories, especially fine kinds of cotton are made here’… ‘The Dutch used to have a manufactory here as well, but they have left it, and the building is a ruin. The manufactory which is now in the possession of the English as well as the whole country used to belong to the French. The factory consists of three substantial houses, built in European style and besides, there are some warehouses to store the goods manufactured here.’

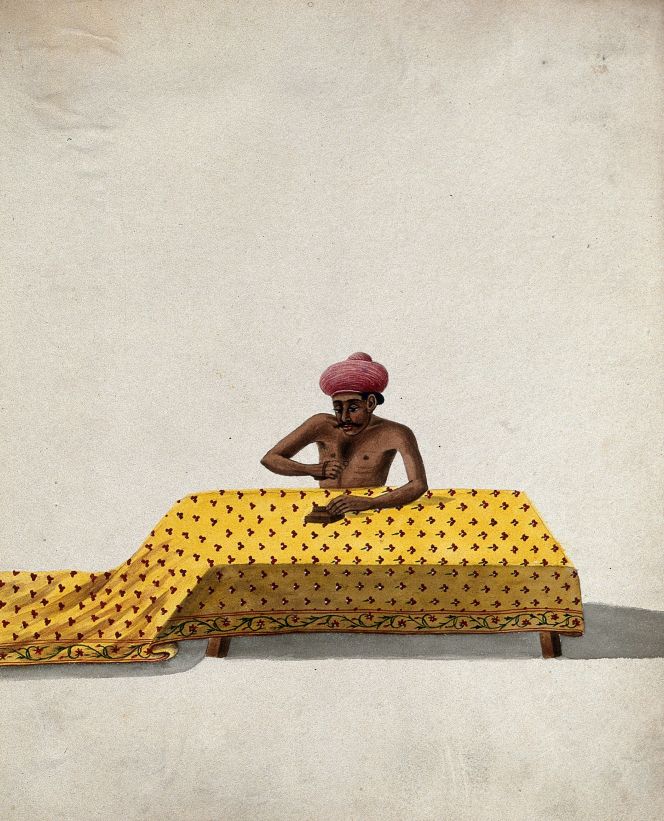

‘A man engaged in block printing a piece of cloth’ – on a gouache painting by an unknown Indian artist, dating circa 1800-1899. This depiction is comparable to König’s reflections on printing forms; he noted: ‘The printing forms are carved of Teak wood, the biggest of them being little more than one foot long and half a foot wide, but I often saw smaller ones according to the motif.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, 582297i, Various Indian trades and professions 18–, album page 27, painting no 28).

‘A man engaged in block printing a piece of cloth’ – on a gouache painting by an unknown Indian artist, dating circa 1800-1899. This depiction is comparable to König’s reflections on printing forms; he noted: ‘The printing forms are carved of Teak wood, the biggest of them being little more than one foot long and half a foot wide, but I often saw smaller ones according to the motif.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, 582297i, Various Indian trades and professions 18–, album page 27, painting no 28).Johann Gerhard König was part of the 18th century network of Carl Linnaeus, Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander and hundreds of others, where textiles from all possible aspects were included to extend one’s knowledge of natural and cultural history. Besides their global scientific curiosity and trading in rare plants. Overall, the travelling Europeans had a general interest in wild growing species and cultivated nutritious or otherwise beneficial plants in visited gardens or plantations established by East India Companies and other parties – all in for them far-flung places. Their observations and collecting were often focused on medicinal uses or food or more specific commodities like tea, sugar, coffee or natural dyes. Live plants, or more easily seeds, could then be transported on ships in their private luggage or sent with other boats from various ports along the sailing routes to be transported over the oceans to reach naturalists, gardeners, et al., who dispersed the rarities to the increasing numbers of European botanical gardens. Gradually, some of these specimens – if hardy enough in the more northerly climes or grown in hot houses – were spread further via shared seeds and cuttings into private gardens. The connection between the local populations of India and the commercial or scientific intentions of the Europeans was one branch of these complex crisscrossing encounters around the globe in the Age of Enlightenment and Colonialism.

In a concluding textile context along the Coromandel Coast, linked to the Europeans, the following description by König gives enlightening details on 20 August 1778 of methods and used dyes in Madepolam [Narsapur]. This place was famous for its cloth trade: ‘After our return, the gentlemen took me to see some of the principal people who print or paint cotton…’

He foremost mentioned the dyeing of red and black cotton, how to get a greenish-yellow colour, the workshop and the necessary tools for the workmen to perform their skills to the highest standard. His tour of the manufacturing works was concluded with some thoughts on fine linen and how the Europeans in the area for many years had marked their presence along the Coromandel Coast: ‘Afterwards, I saw the great ponds, used to bleach the fine kinds linen, and ended up by visiting the graves of the first Europeans, over which monuments as big an in the shape of houses have been erected ornamented with rich sculpture. Amongst them was also that of an English lady buried here almost a hundred years ago…’.

Sources:

- Brimnes, Niels, ed., Indian: Tranquebar, Serampore og Nicobarerne, Denmark 2017.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles: Global Science & Adventure, Vol. One, 2010 (in Sörlin, S., ‘The Apostles’, pp. 151-179).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Howgego, Raymond John, Encyclopedia of Exploration to 1800, Australia 2003 (p. 578).

- Koenig [König], Johann Gerhard, ‘Journal of a voyage from India to Siam and Malacca in 1779’. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 26, pp. 58-200 & part II. pp. 57-133, 1894. [Quotes pp. 62, 66-67 & 70-73 (Translated from his Manuscripts in the British Museum: today at the Natural History Museum London).

- Manning, Patrick & Rood, Daniel, ed., Global Scientific Practice in an Age of Revolutions, 1750-1850, Pittsburgh 2016.

- The Linnean Society (The Linnaean Correspondence Collection, online).

- Wellcome Library, Online Collection (factual information about the map and two textile images).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE