ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILE OBSERVATIONS

– from an 1841 Plan of Whitby

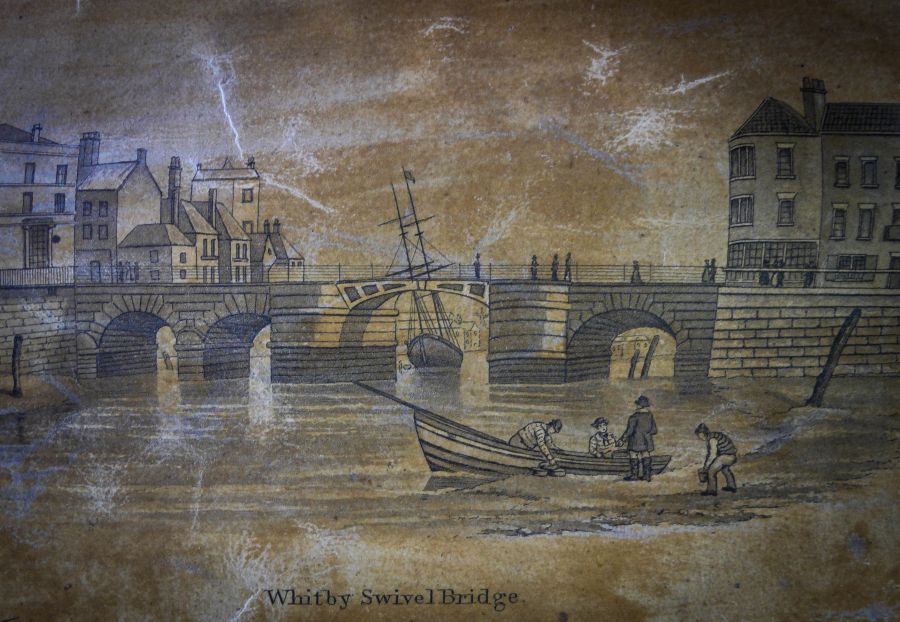

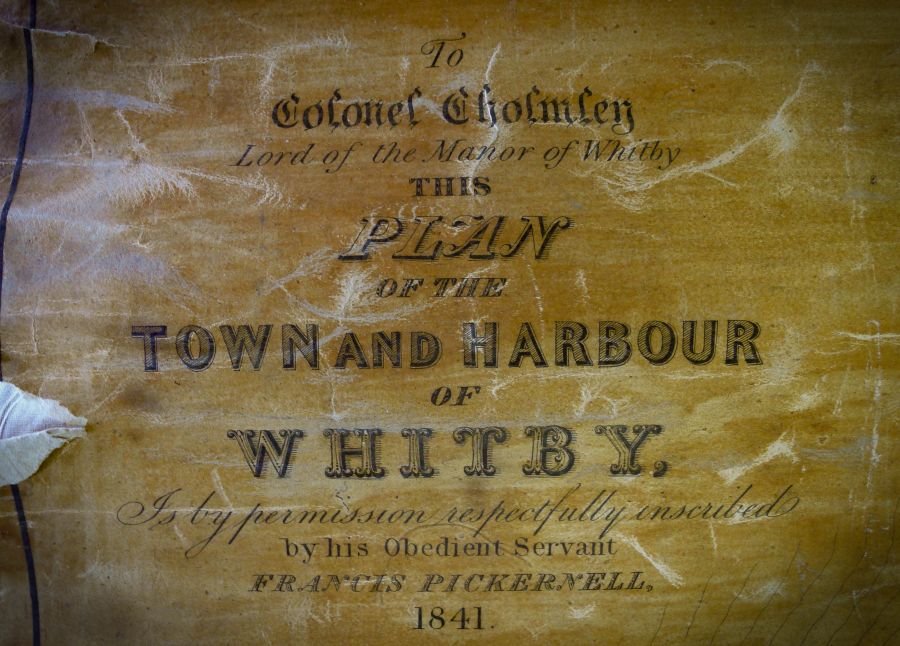

Maps and plans can often be valuable and informative primary sources for textile history research. This plan by Francis Pickernell over the coastal town of Whitby, printed in 1841, is such an example, with its accompanying illustrative pictures. These images include, together with town buildings, the Bridge, West Pier and lighthouse, inhabitants out for a walk in their contemporary clothes and fisherfolk in both single-coloured and striped upper garments. The essay aims to give a detailed study of this particular plan and an overview of earlier maps in the area – from the perspectives of textile manufacturing, clothing and the alum trade so crucial for natural dyes, among other areas of use.

One of the illustrations in ‘Francis Pickernell’s plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby 1841’, shows fishermen in sweaters, waistcoats and jackets by the water’s edge, even if the main focus is the rather newly built bridge. Though it should be remembered that the people illustrated in old landscapes or town street scenes are often standardised – or even beautified – to demonstrate the clothes worn by a variety of social classes and occupations. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

One of the illustrations in ‘Francis Pickernell’s plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby 1841’, shows fishermen in sweaters, waistcoats and jackets by the water’s edge, even if the main focus is the rather newly built bridge. Though it should be remembered that the people illustrated in old landscapes or town street scenes are often standardised – or even beautified – to demonstrate the clothes worn by a variety of social classes and occupations. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Other maps and plans researched for the monograph The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914, preceding Pickernell’s, were varied in style and outlines. The earliest detailed street maps that include alleys, the river, the harbour, gardens, churches and the ropery, etc., are most in evidence in the years 1734, 1740 and 1778. However, there are no details specific to textile activities on these maps, such as places of manufacture and areas for bleaching, dye works, or similar businesses. However, maps from 1782, 1803, 1826, 1828 and 1833 portrayed some more features of interest. Francis Gibson’s map dated 1782, for example, shows an ‘Allum Works’ situated outside Whitby, and even if most of the alum was transported by sea, a narrow road leads to Whitby from this factory. Saltwick Bay was relatively short-lived as a producer of alum in the area – from 1749 to 1791 – and this map gives the only known indication of the extent of this alum works. Gibson also produced a map of Whitby and its neighbouring coastline in 1803, mainly intended for sea navigation, but the map also shows windmills, rope-walks, the new “Poor Law Union” workhouse and shipyards, etc. John Wood’s extremely precise plan of Whitby and its environs, dated 1828, was the first professionally surveyed map. It not only shows clearly that the town had increased in size, but also includes the names of many property owners, yards and other useful information. From the textile point, ‘Silk Dyers & Watson’s Yd’ on Church Street is added, implying that silk and silk fabric were dyed there.

![West Pier and Lighthouse, on the same 1841 plan, gives for example a good impression of men’s clothes at that time. Even though they are some distance away from us, the family strolling on the West Pier can be seen to include a man typical of the period in day wear, with a rather tall black hat and a short dark jacket over a lighter-coloured waistcoat and even lighter long trousers. It is not possible to make out more detail, but he is probably wearing a white shirt and carefully knotted tie. The two daughters [or mother and daughter] are depicted in identical clothing including white aprons. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-pickernells-plan-900x638.jpg) West Pier and Lighthouse, on the same 1841 plan, gives for example a good impression of men’s clothes at that time. Even though they are some distance away from us, the family strolling on the West Pier can be seen to include a man typical of the period in day wear, with a rather tall black hat and a short dark jacket over a lighter-coloured waistcoat and even lighter long trousers. It is not possible to make out more detail, but he is probably wearing a white shirt and carefully knotted tie. The two daughters [or mother and daughter] are depicted in identical clothing including white aprons. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

West Pier and Lighthouse, on the same 1841 plan, gives for example a good impression of men’s clothes at that time. Even though they are some distance away from us, the family strolling on the West Pier can be seen to include a man typical of the period in day wear, with a rather tall black hat and a short dark jacket over a lighter-coloured waistcoat and even lighter long trousers. It is not possible to make out more detail, but he is probably wearing a white shirt and carefully knotted tie. The two daughters [or mother and daughter] are depicted in identical clothing including white aprons. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen. Francis Pickernell (1796-1871) was not only the maker of this large-scale and professionally surveyed plan of Whitby, already from 1822 he worked as an harbour engineer in the coastal town and built the swing bridge in 1835 among other local constructions. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

Francis Pickernell (1796-1871) was not only the maker of this large-scale and professionally surveyed plan of Whitby, already from 1822 he worked as an harbour engineer in the coastal town and built the swing bridge in 1835 among other local constructions. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen. The plan is also the first detailed map including the railway line between Whitby and Pickering, which only been in existence for five years in 1841 (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

The plan is also the first detailed map including the railway line between Whitby and Pickering, which only been in existence for five years in 1841 (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.This new railway had considerable influence in that the conveyance of all kinds of goods, as well as an increase in passenger traffic, were able to function on a more rational basis than before. The horse-drawn wagons of Whitby’s first railway link to Pickering in 1836 were replaced by locomotives in 1847. This and later railway lines branched out further into a network which came to link up most parts of the country, which from the point of view of textiles meant that people handling all types of clothes and material in Whitby had good communications with Leeds and its neighbouring towns where the production of textiles had one of its centres during the whole of the Victorian and Edwardian era. Even if the development of the railways was decisive for this rapid development, it was still possible to travel by coach to villages unconnected with the railway network, while coastal traffic with steamers was extensively used to transport both passengers and goods.

The last detail of the 1841 plan shows River Esk, the Ship Yards, Ropery etc. Rope-making which needs textile raw materials – hemp or flax – is a specialised subject beyond the boundaries of the publication about the textile history of Whitby. But studies of hemp and flax, the ships yards and the importance of River Esk were studied for Chapter IV: ‘Sailcloth Manufacturing and Sailmaking’. This is a comprehensive study stretching over 40 pages, which was assisted by information found on various local maps and plans among numerous other primary sources. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

The last detail of the 1841 plan shows River Esk, the Ship Yards, Ropery etc. Rope-making which needs textile raw materials – hemp or flax – is a specialised subject beyond the boundaries of the publication about the textile history of Whitby. But studies of hemp and flax, the ships yards and the importance of River Esk were studied for Chapter IV: ‘Sailcloth Manufacturing and Sailmaking’. This is a comprehensive study stretching over 40 pages, which was assisted by information found on various local maps and plans among numerous other primary sources. (Whitby Museum, Map Collection). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 18-24).

- ‘Plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby…Francis Pickernell 1841’ (Whitby Museum, Map Collection).

- Whitby Gazette, 1855-1900 (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE