ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILE PRODUCTION AND TRADITIONS

– from 1525 to 1650 in a Coastal Town

A relatively large number of textiles from the period 1525-1650 are kept in the Malmö Museum collection – mostly purchased from Italy, Spain and other countries in the 20th century – but it is only a limited number that with certainty can be traced to local citizens and their everyday life from this part of the early modern period. Like the well-preserved purse depicted below from 1602, fragments of knitted garments, a thimble and silver buttons. This essay will briefly put these textile remnants, etc., in their historical context, as assisted by earlier research of local estate inventories. A range of other handwritten documents and a portrait together give quite a clear idea of the textile production and material culture in these years.

This well-preserved purse was used for safe-keeping of valuable seals by the carpenter’s guild in Malmö, 1602. The purse was made of an exquisite cut velvet on a satin ground, stitched together of four fabric pieces, whilst the seams are decorated with a fragmented chain stitch embroidery of metallic gold thread. The purse was probably made of leftover pieces from a garment or interior textile. Holes were placed with regular intervals to pull a string/cord through – not preserved today – and the purse was lined with an unbleached linen. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM000139:002, Creative Commons).

This well-preserved purse was used for safe-keeping of valuable seals by the carpenter’s guild in Malmö, 1602. The purse was made of an exquisite cut velvet on a satin ground, stitched together of four fabric pieces, whilst the seams are decorated with a fragmented chain stitch embroidery of metallic gold thread. The purse was probably made of leftover pieces from a garment or interior textile. Holes were placed with regular intervals to pull a string/cord through – not preserved today – and the purse was lined with an unbleached linen. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM000139:002, Creative Commons).In 1559, the Danish King Fredrik II was to be crowned in Copenhagen; for this occasion, a contemporary document stated that interior textiles, among other matters, had to be borrowed from the castle Malmöhus and the townsmen of Malmö, including ’100 tablecloths, 10 beds with bolsters, pillows, cushions, sheets, Flemish bed clothing and other…’. This list demonstrates some of the textile prosperity that existed in wealthy homes in the mid-16th century Malmö, while most homes owned a selection of “necessary textiles” depending on economic circumstances. The realities of ownership and the number/type of textiles in various strata of society can foremost be studied via preserved estate inventories, including various fabrics for the home as well as clothing owned by the deceased.

The Malmö major Jørgen Kock’s portrait dating 1531 has already been mentioned in an earlier essay in this series, but is repeated in this context whilst it was very rare in the Nordic area to be portrayed in this time if not being Royal. Furthermore the painting gives a unique understanding of a wealthy man’s clothing in 1530s Malmö. He is wearing a wide lace collar, a linen shirt can be seen at the wrists, a red upper garment of silk/broadcloth, elegant gloves with possible embroidered details and a fine black cloak. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons).

The Malmö major Jørgen Kock’s portrait dating 1531 has already been mentioned in an earlier essay in this series, but is repeated in this context whilst it was very rare in the Nordic area to be portrayed in this time if not being Royal. Furthermore the painting gives a unique understanding of a wealthy man’s clothing in 1530s Malmö. He is wearing a wide lace collar, a linen shirt can be seen at the wrists, a red upper garment of silk/broadcloth, elegant gloves with possible embroidered details and a fine black cloak. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons).The late textile historian Ernst Fischer gave many examples of the townsmen’s textiles from late 16th century homes in Malmö, which were researched from estate inventories and other archival sources. One such informative description was as follows: ‘In 1594 Nils Guldsmed and his wife Bengta had 1 bench cover and 1 travel cushion, both embroidered, 3 Flemish tapestry bench covers of which one was old and one of the other had the considerable length of 10 alnar [ca 6 metres]. Furthermore, they owned 7 long Flemish tapestry cushions, of which one had a pattern of faces. Finally, on the beds was 1 Danish bedcloth, 2 piled rugs, one old and one new, and also 2 leather bed covers’. It must be noted that the “Flemish tapestry” was a tapestry type not necessarily woven in Flanders, but instead most probably produced in Malmö by local weavers.

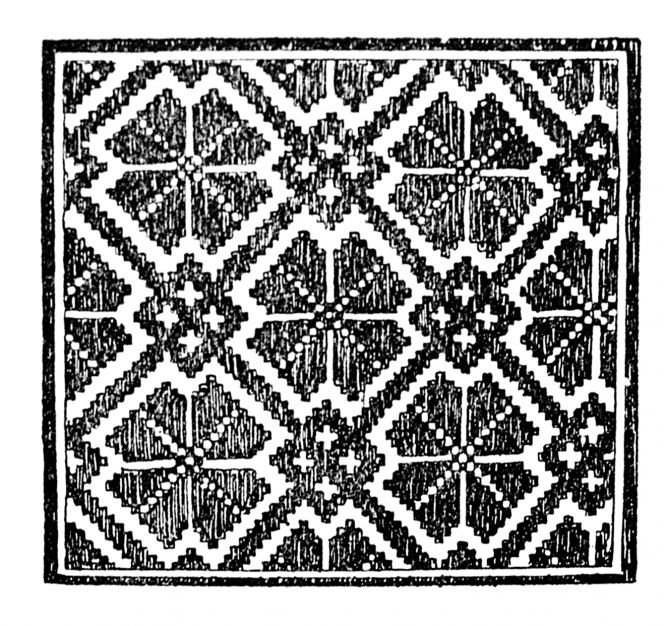

Illustration from the book ‘Esemplario di Lavori’ originally printed in 1529, a rich selection of such books were printed in Italy, France and Germany in the early modern period. Prints like these are believed to have had significant influence of the spreading of geometrical Renaissance motifs to the Nordic area – inspiring weavers, embroiderers, lacemakers and the like to copy or adjust the designs for their needs. (Zoppino… Facsimile, Venezia 1878).

Illustration from the book ‘Esemplario di Lavori’ originally printed in 1529, a rich selection of such books were printed in Italy, France and Germany in the early modern period. Prints like these are believed to have had significant influence of the spreading of geometrical Renaissance motifs to the Nordic area – inspiring weavers, embroiderers, lacemakers and the like to copy or adjust the designs for their needs. (Zoppino… Facsimile, Venezia 1878).Proofs that the selling of similar pattern books existed can be traced via an estate inventory of art merchant Thomas Bell in Malmö, 1617. Among many other articles, the merchant left ‘4 books to make lace and stitch in imitation of…1 dlr.’. Malmö estate inventories included substantial numbers of embroidered cushions, etc, already in the second half of the 16th century. The tapestry or “Flemish” weaving was another textile art form on the increase in Malmö, often based on pattern book-styled designs. Due to studies of a large selection of local estate inventories, Fischer’s research also revealed that this technique became common in the townsmen’s homes in the early 16th century and continued to increase in popularity up to 1650.

The Malmö Museum collections include a number of “silver treasures” unearthed in various parts of the old town, these 72 silver buttons were discovered in the area of Druvan in 1888. Buttons of this type originate from the first half of the 17th century, and was used by the townsmen and other wealthy citizens to fastening various garments. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM003591:006, Creative Commons).

The Malmö Museum collections include a number of “silver treasures” unearthed in various parts of the old town, these 72 silver buttons were discovered in the area of Druvan in 1888. Buttons of this type originate from the first half of the 17th century, and was used by the townsmen and other wealthy citizens to fastening various garments. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM003591:006, Creative Commons).Broadcloth and wadmal for the Malmö citizens’ needs were both imported and produced by local weavers. The import was substantial, and the English qualities were regarded as superior. However, it is impossible to be sure of the proportion between domestic woollen fabrics and the import. When an estate inventory lists a loom, it is unclear if this tool was used for woollen or linen cloth. Furthermore, the professional woollen weavers were few in this period; for example, only two in 1596, while the linen weavers numbered fourteen.

The local linen trade was also thoroughly researched by Ernst Fischer, giving detailed information about the many masters, journeymen and apprentices. The linen weavers guild in Malmö was introduced in the mid-16th century – producing bed linen, blue-striped fabric for bolsters, tablecloths, napkins and linen for clothing for the population. The demand and popularity for all types of linen wares substantially intensified at the end of this century, meaning that flax was growing as well as the number of weavers increased, making professional linen weaving an important occupation/trade in the period 1550 to 1650.

This somewhat flattened silver thimble was also unearthed in 1888 from the area Druvan, like the silver buttons above. A tool that had a very similar appearance already in the Medieval period, used either by a tailor or lady sewing her own linen garments. Dating from the first part of the 17th century or earlier. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM003591:020, Creative Commons).

This somewhat flattened silver thimble was also unearthed in 1888 from the area Druvan, like the silver buttons above. A tool that had a very similar appearance already in the Medieval period, used either by a tailor or lady sewing her own linen garments. Dating from the first part of the 17th century or earlier. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM003591:020, Creative Commons).Four knitted woollen fragments found during archaeological excavations also add knowledge to the clothing used by Malmö citizens in this period. To knit garments with two or more needles was at least known already in the 1380s on the Continent, but no Medieval finds of this increasingly popular elastic technique for clothes have been found in the Nordic area. Two of the earliest Malmö fragments of knitted wool – excavated in an earth closet in the St Gertrud area – have been dated to the 16th century. One of the tiny pieces was plain stitched without any types of patterns (4560: 19), 2,5 stitches x 3 rows/cm, a pretty fine quality with a 2-ply yarn. Meanwhile, the second fragment (4560: 6) is garter-stitched and has a coarser structure. The two other fragments are somewhat larger and have been dated to the first half of the 17th century. Including a fragmented plained stitched cap (MHM 1813) unearthed in 1969 in the area of Ellenbogen, whilst the remnants of a pair of mittens (MHM 648) were found seven years earlier in the area of Stadt Hamburg. The plain stitched mitten was particularly fine in quality, with four stitches x six rows/cm; the garment also includes decorative simple purl/plain stitch patterning. One can conclude that the knitter of these mittens must have used extremely thin knitting needles to achieve this extraordinary fine quality.

Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. Quotes are translated from Danish/Swedish to English. Meanwhile, numbers within brackets refer to Malmö Museum catalogue cards. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish articles by Viveka Hansen, published in 2000 and 2001.

Sources:

- Fischer, Ernst, Linvävarämbetet i Malmö och det skånska linneväveriet, Malmö 1959.

- Fischer, Ernst, Flamskvävnader i Skåne, Malmö 1962.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Kyrkliga textilier i Malmö – från medeltid till barock’, Elbogen pp. 61-135. 2000.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Förhistoriska och Medeltida Textilier i Malmö’, Elbogen pp. 73-144. 2001.

- Malmö Museum, Sweden (Online collection, three images & information from catalogue cards).

- Zoppino, Nicolo d’Aristotile, Esemplario di lavori, Facsimile, Venezia 1878.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE