ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILE REFLECTIONS: 1770 to 1840

– By two Antiquarians in the Coastal Town of Whitby

Local history was quite a common interest for independent individuals, parish priests, geographers, teachers, et al. in England and similarly so in many other countries during the period 1770 to 1840. They were often regarded as antiquarians (not as historians or archaeologists) at the time and aimed to learn more about almost everything from a historical and for them present-day perspective. This included ancient monuments, landscapes, architecture, churches in the vicinity, trade routes affecting the area, manners and customs or manufacturing of textiles. Such written materials could result in printed books, or the amassed texts stayed as unprinted reports or documents. Whitby in North Yorkshire was no exception, which this essay will observe more closely. Two young men with several years of study at Edinburgh University, moved to Whitby more than half a century apart to work in their respective professions, together they came to register this area from all possible angles during a 70-year period.

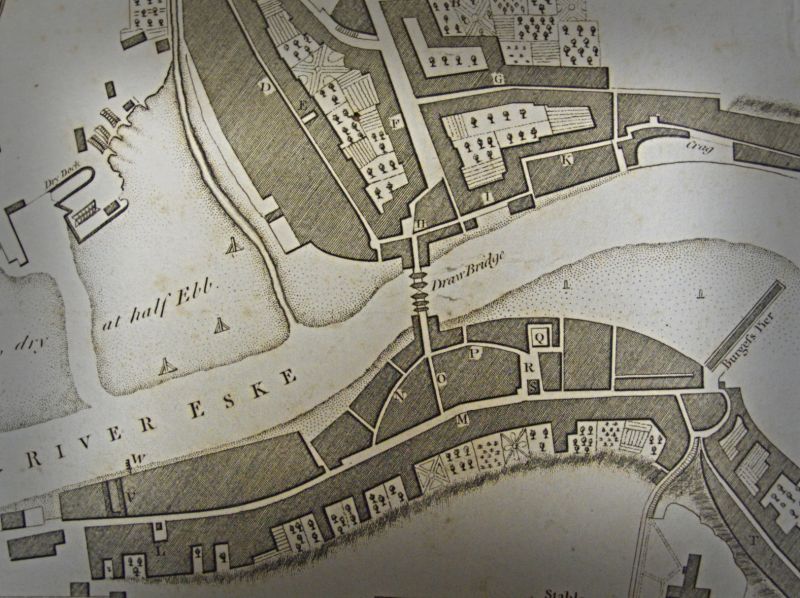

Whitby during the 1770s, with the streets of origins in the Middle Ages, gathered on each side of the ‘Draw Bridge’ and at this time many of the properties still had large gardens. |‘Plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby. Made in the Year 1778…’ Part of Lionel Charlton’s book in the following year. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Plans and Views of Whitby 769.942.74, part of the map). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Whitby during the 1770s, with the streets of origins in the Middle Ages, gathered on each side of the ‘Draw Bridge’ and at this time many of the properties still had large gardens. |‘Plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby. Made in the Year 1778…’ Part of Lionel Charlton’s book in the following year. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Plans and Views of Whitby 769.942.74, part of the map). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Lionel Charlton (1720–1788) moved to Whitby in 1748 and worked as a land surveyor and school teacher. Judging by his in-depth publication, printed in 1779, he had collected information over many years, but it was unknown when he started to write. The main part of the book describes historical observations from far back in time, particularly from the Middle Ages, whilst this essay will focus on observations of textile manufacturing, philanthropy, and general notes linked to such everyday matters in Whitby during his lifetime.

The second antiquarian was the Presbyterian minister George Young (1777-1848), who also moved from Scotland to Whitby, this was in 1806, a place where he came to work for the rest of his life. Young published more than 20 books, with a systematic approach which evolved his work over the years. Three of these books have been studied from a textile perspective. For instance, in 1840 he wrote about the whaling trade. ‘The principal articles exported or carried coastwise from Whitby are alum, whale oil, whale fins, sailcloth, dried fish, butter, hams and bacon, oats leather and freestone’. This list included two products from this lucrative trade, of which whale oil was the most profitable. So far as textiles were concerned, whale oil was useful for washing wool free of fat, while whale bones/baleen [also called fins] were used among other things for strengthening women’s stays/bodices during various periods of fashion. The lucrative whaling business began as early as 1753 when the first two ships set out from the town for Greenland. The whaling trade reached its peak in 1786-88 when twenty Whitby ships were involved, to be reduced to between about seven and twelve ships leaving Whitby for northern waters each year up to 1840.

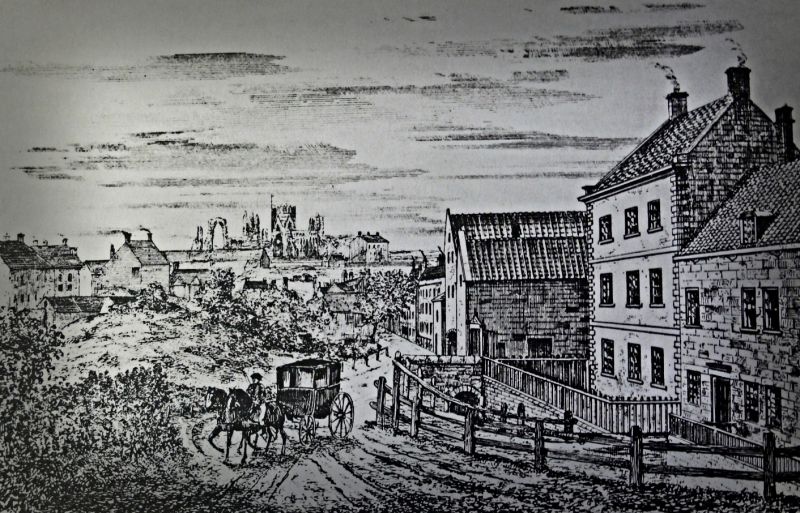

‘Whitby from Bagdale’ in 1794 with the Abbey at a distance. A depiction which gives a glimpse of travel with a horse-drawn carriage on one of the many steep roads in town, just a few years after Lionel Charlton’s death and in the decade prior to George Young’s arrival in this town. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Dr. English Prints). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

‘Whitby from Bagdale’ in 1794 with the Abbey at a distance. A depiction which gives a glimpse of travel with a horse-drawn carriage on one of the many steep roads in town, just a few years after Lionel Charlton’s death and in the decade prior to George Young’s arrival in this town. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Dr. English Prints). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Poverty, workhouses, philanthropy and such developments in Whitby over more than a hundred-year period, were reflected upon by Charlton as well as Young in the respective publications. For people being economically dependent on society was usually caused by old age or long-term or sudden illness, or in the case of a child being without parents, or being an unmarried mother with a child or, in the case of young or middle-aged people, being out of work. In addition, subsequent census returns from the local area show that elderly dressmakers, washerwomen and tailors together with people from many other categories of occupation have not seldom ended their lives in conditions like this:

Lionel Charlton in 1778;

- ‘In the year 1726, a workhouse was first instituted at Whitby under the auspices of Hugh Cholmley, Esq; who was the Lord of the Manor, and gave the ground. Money was raised for this purpose by the voluntary contributions of the inhabitants; and Mr Thomas Clark, who was then chief constable for Whitby-Strand, had the direction of the buildings. Here the poor have been maintained and lodged ever since; but they are now much straitened in their quarters, on account of the great increase of inhabitants (and consequently of poor) within the town of Whitby during these fifty years last past, which will, in a little time, make some new regulations absolutely necessary with regard to this workhouse.’

George Young in 1840;

- ‘The first workhouse...The paupers at that time, and for many years after, seldom exceeded 40; but when, through the great increase in our population, they began to exceed 70, the necessity of a larger poor-house became apparent; and in 1793 and 1794, the present spacious house was built by subscription, in a most pleasant and healthful situation, adjoining to Green lane.’

- Young also noted the need for warm clothes for the poor during the cold part of the year. ‘The Dorcas Society, a charity for clothing the aged female poor, was founded in 1814.’ This society was run by twelve ladies who with the help of collected clothes remade and altered clothing so that ‘... about 450 women are supplied in the winter with useful articles of clothing.’

Another branch of interest for Georg Young – almost contemporary with his portrait below, was Whitby Museum – Whitby Literary & Philosophical Society – founded in Whitby Town Hall on 17 January 1823 (celebrating 200 years in the year and month of this essay). The Museum’s main aim over the coming decades was to collect objects linked to geology, archaeology and natural history – fossils (or ‘petrifications’) were of particular interest at a time when Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) discoveries and theories first attracted popular attention. These areas interested the original founders and many of their successors, whether professional or amateur, not to mention the Museum’s 19th century visitors. This is how Young, one of the Museum’s first promoters, described its earliest days in his 1840 book: ‘The Museum is situated in Baxtergate, and already contains a rich collection of petrifications, minerals, rock specimens, fossil bones and teeth..., antiquities, shells and miscellaneous curiosities.’

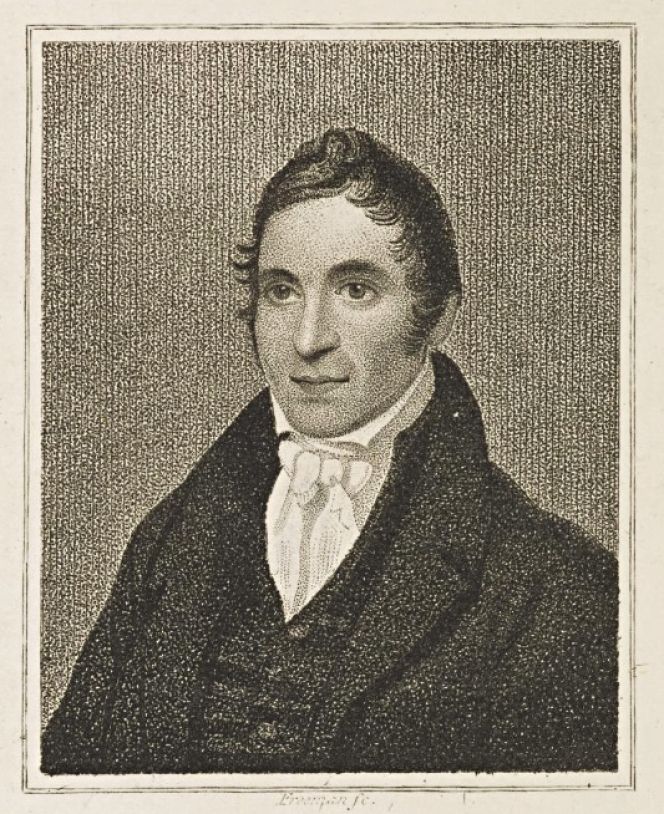

Portrait of George Young in 1820, work on paper by Freeman. (Courtesy: National Galleries Scotland, No: UP Y 19).

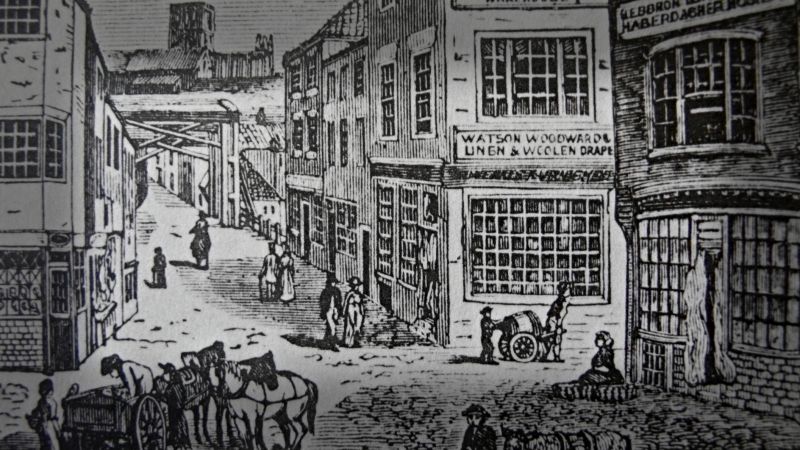

Portrait of George Young in 1820, work on paper by Freeman. (Courtesy: National Galleries Scotland, No: UP Y 19). The thorough historical studies by the two local antiquarians also give information on other textile activities during the period from 1779 to 1840, together with more sporadic observations of visitors. Young’s 1817 book on Whitby for example, reveals an interesting fact about the tradesmen and manufacturers of the day, mentioning 30 drapers. He even suggests that there might be too many of them: ‘Their number is at present too great for all to prosper’, which can also be understood from the fact that the town contained 69 ‘tailors, including staymakers’. Other tradesmen with textile connections were ‘5 cabinetmakers and upholsterers’ and ‘6 slop-shops’ – shops which sold inexpensive or good-value second-hand clothes. | Close-up detail of a contemporary image, which shows the Haberdashery shop etc at the Old Market Place in Whitby 1818. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Dr. English Prints). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The thorough historical studies by the two local antiquarians also give information on other textile activities during the period from 1779 to 1840, together with more sporadic observations of visitors. Young’s 1817 book on Whitby for example, reveals an interesting fact about the tradesmen and manufacturers of the day, mentioning 30 drapers. He even suggests that there might be too many of them: ‘Their number is at present too great for all to prosper’, which can also be understood from the fact that the town contained 69 ‘tailors, including staymakers’. Other tradesmen with textile connections were ‘5 cabinetmakers and upholsterers’ and ‘6 slop-shops’ – shops which sold inexpensive or good-value second-hand clothes. | Close-up detail of a contemporary image, which shows the Haberdashery shop etc at the Old Market Place in Whitby 1818. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Dr. English Prints). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The sewing of sails had a long tradition in Whitby, as Georg Young made clear in his publication of 1817: ‘The sailcloth-manufactories are comparatively modern; for before the year 1756, the Whitby sailmakers procured the canvas from other places.’ It has not been possible to prove from other sources that the weaving of sails was introduced to the town in that very year, but it is extremely likely to have been around that date. What can be proved, however, is that categories of workers such as flax dressers and weavers appeared earlier in the Whitby parish church registers, especially during the 1730s and 1740s. However, it is not possible to be sure whether these skilled workers prepared linen material to be used for sails, or for clothes and interior furnishings. Yet sailmaking had existed on a small scale since at least the 1710s and increased with every decade to reach its greatest extent during 1770-1840, the peak period of sailcloth weaving in Whitby. During this climax, the town had either three or four weaving mills to supply the many sailing vessels with sails.

Even if times of war ensured the production of exceptionally large quantities of canvas – mostly not for local consumption – weaving continued on a large scale throughout this productive era. This can be confirmed from several sources, first from the parish church registers in particular, where it is possible to trace those connected with this work up to the year 1837; and after that in the censuses from 1841 onwards, and in Georg Young’s books published between 1817 and 1840. According to Young, as many as 5,000 yards of sailcloth a week were still being produced in 1782, increasing to 7,400 yards in 1796-1805. During 1805-1815 production stood at about 5,400 yards, finally growing to no less than 9,000 yards a week in 1840. This increased production at the end of the period did not signify that a greater number of workers were involved; rather the opposite, judging by the parish church registers of the late 1830s and the 1841 census – the fact was that more weaving was now being done on mechanically assisted looms making an increased rate of production possible. Using a now-lost census dated 1816, Young writes that in that year, Whitby had 40 sailmakers, 104 weavers and 39 flax dressers.

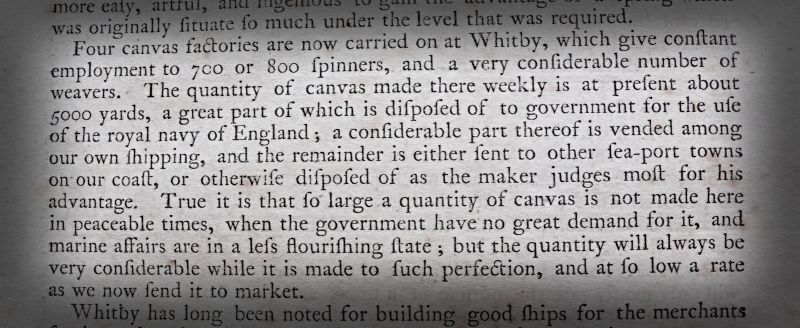

In the earlier notes written by Lionel Charlton, he set down some interesting observations on the considerable quantity of cloth produced by the four canvas factories of the time and how it was used. (From the book: Charlton…1779 p. 358).

In the earlier notes written by Lionel Charlton, he set down some interesting observations on the considerable quantity of cloth produced by the four canvas factories of the time and how it was used. (From the book: Charlton…1779 p. 358).Lionel Charlton also commented briefly on the importance of foreign imports of raw material in his book printed in 1779: ‘From Holland we import flax’ and ‘From the East Country we have hemp, flax...’. Together with a record of the number of spinners needed to provide the weaving-mills with yarn for this kind of spinning-wheels in the age of hand-spinning: ‘Four canvas factories were now at work in Whitby, giving steady employment to 700 or 800 spinners...’

A few decades later, the existence of a new local spinning factory was a revolutionary change described in George Young’s book of 1817:

- ‘Till lately the spinning was all performed in private houses, as a great part of it still is: but in 1807, Mr. Campion erected a spinning-manufactory, beside his sailcloth manufactory in Bagdale. In 1814 this spinning manufactory gave place to another, which the same gentleman erected beside it, on a larger scale and an improved plan. It contains 12 spinning frames, each having 30 or 36 spindles; besides carding frames, preparing frames, and other ingenious machinery; the whole driven by an excellent steam-engine, of 12 horse power, by Fenton, Murray and Wood. The manufactory employs from 30 to 40 people, and can spin about 250 dozen lbs. in a week. It could be made to produce much more, being capable of containing several additional frames.’

Additionally, Young’s notes give valuable information on the development of sail-weaving in Whitby, both concerning the location of the weaving-mills, who owned them, and the number of looms. These matters were described thoroughly in the same book printed in 1817, at a time when the three mill owners possessed a total of 93 productive looms:

- ‘There are now three manufactories for canvas established here...The first was begun about the year 1756, by the late Mr. Jon. Sanders. It comprises two, or rather three branches; one near the Market Place, containing 11 looms; one in Tate hill, containing 16 looms; and one at Guisborough, of about the same number. The second manufactory also consists of two branches; one in Church street, containing 21 looms; and one in the vale above Bagdale, containing 15 looms. These were formerly two distinct manufactories. That in Church street was begun by Mr. Christ. Preswick in 1758: it was first carried on at Ruswarp, but, the premises there being destroyed by fire, it was removed to Boulby bank, near to the house and bakehouse now occupied by Mr. Readshaw; from whence it was transferred, in 1777, to Elbow yard, where it is now carried on. The Bagdale branch of this manufactory was begun by a Mr. Christ. Ware about the year 1759. The third manufactory, which contains 30 looms, is beside Spital bridge. It was begun in the year 1767, by the family to whom it still belongs.’

As a concluding quote from his book printed in 1840, George Young still had some informative remarks on the owners of the weaving-mills and their productions: ‘The present manufactories are three in number; viz. that of Messrs J. & W. Chapman, near Spital bridge; that of Mr. Impey, in the upper part of Bagdale; and that lately begun by Messrs T. & J. Marwood, in Flowergate. The canvas business is at present uncommonly brisk...’ However, just a few years after Young’s death in 1848, the 1850s and further on came to see a steep decline in the weaving of sailcloth in Whitby, particularly evident in the 1851 census.

Sources:

- Charlton, Lionel, The history of Whitby and of Whitby Abbey, York 1779.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 22-23, 32-34, 53, 143-46, 153 & 162-63. [Extra notice: The complete research about sailcloth manufacturing and sailmaking in Whitby, pp. 142-171].

- National Galleries Scotland (Portrait of G. Young, 1820, Mrs A.G. Macqueen Ferguson Gift 1950).

- Sweet, Rosemary, Antiquaries: the Discovery of the Past in Eighteenth-Century Britain, London 2004 (Quote – Introduction; p. XV).

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, & Map Collection (Whitby Lit. & Phil.) Parish Church Registers, maps & other local historical documents.

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1841-1871 microfilm).

- Young, George, A History of Whitby, Vol. I-II 1817.

- Young, George, A Picture of Whitby and its Environs, Scarborough, Stockton 1824.

- Young, George, A picture of Whitby and its Environs, Whitby 1840.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE