ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

TEXTILES IN SWEDISH HOMES (part 1)

– A Documentation of Estate Inventories in the Blekinge Province: 1770 to 1870

A study of preserved textiles and estate inventories from the Blekinge province reveals that families favoured a rich selection of furnishing textiles; many such treasures were often only used at festivities and an essential part of the young woman’s dowry. The farmers, well-to-do merchants, crofters, fishermen or priests – owned textiles in capacity after each and everyone’s means. Differences were substantial, as in other Swedish provinces, not only between the various strata of society but also between the countryside and the city over this one-hundred-year period. It may be mentioned, too, that even people experiencing poverty sometimes had more textiles than expected, but often, there were never any recordings made for poor households. This is the first in a two-part essay, which will look closer at these traditions based on in-depth research of 1313 estate inventories selected from 1770, 1790, 1810, 1830, 1850 and 1870.

This postal map, dating to the 1750s, gives a good understanding of the geographical situation of the Blekinge province along the Baltic Sea. The largest city, ‘Carlscrona,’ to the east, had four districts divided into four similarly sized areas. From an easterly direction, Östra, Medelstad, Bräkne and Lister districts – of which the final district bordered the most southerly province, Skåne of Sweden. (Courtesy: Post Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: POST.044523. DigitaltMuseum)

This postal map, dating to the 1750s, gives a good understanding of the geographical situation of the Blekinge province along the Baltic Sea. The largest city, ‘Carlscrona,’ to the east, had four districts divided into four similarly sized areas. From an easterly direction, Östra, Medelstad, Bräkne and Lister districts – of which the final district bordered the most southerly province, Skåne of Sweden. (Courtesy: Post Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: POST.044523. DigitaltMuseum)No exact information exists about which furnishing textiles were considered necessary in the Blekinge province's homes during this period. Basic needs, financial possibilities, one’s societal position and local traditions managed such demands altogether. Unsurprisingly, an individual could own nothing to an abundance of textile treasures and linen. All textiles – excluding clothes – were looked at closely during the studies of these estate inventories. The recorders had been especially attentive overall regarding the more valuable items, like linen sheets with embroidery and lacework, tablecloths woven in diaper or damask, tapestries, and featherbeds. As the research proceeded, observations were sorted and listed in twenty-seven textile groups. The material will be described and put in a historical context via this two-part essay – translated and worked up from my Swedish article published in 1998 and partly added with new images to shed light on this relatively unknown textile history for an English reading audience.

Everyday textiles, functional for warmth and comfort, dominated the furnishing fabrics listed in the estate inventories. These were recorded as bed linen, featherbeds, woollen cushions, pillows and bed curtains. Traditional decorative and more luxurious textiles were kept in substantial numbers in many homes within the province. In particular, embroidered bed curtains, art-woven cushions and bedcovers are equally the finest woven table linen.

Cushions and covers for chairs, benches and carriages

To be comfortably seated before the tradition of upholstered furniture, portable cushions and pads fulfilled this function. These estate inventories, which originated from the four districts (Lister, Bräkne, Medelstad, Östra) and the largest city, Karlskrona in Blekinge, give proof that the square-shaped cushion, circa 50x50 cm, and the oblong sized cushion measuring about 50x100 cm were used in all districts. However, all sorts of moveable seat cushions became less and less prevalent as time passed, becoming almost non-existent in the documents from 1850. This was due to changing traditions. Benches placed along the walls and uncomfortable wooden chairs were seen as unfashionable in farming communities, too, when upholstering of armchairs, sofas, etc., gradually became accessible for more families during the 19th century. Weaving or embroidery techniques were occasionally mentioned in these handwritten documents, but judging by preserved textiles from this geographical area, a significant variation in techniques and colours existed. Foremost handwoven in double-interlocked tapestry, dove-tail tapestries and the weft-patterned techniques krabbasnår, halvkrabba, dukagång, opphämta or munkabälte likewise as woven rosepath (rosengång) and embroidered designs. When such details had managed to be identified by the recorders and added to the estate inventories, most commonly, these textiles were noted as ‘embroidered cushion’, ‘tapestry’ or ‘entangled cushion’. For instance, the local tapestry type, which was particularly common in the most eastern district (Östra), seems to have had a peak of popularity around 1790, at a time when a total of 43 such tapestry cushions were listed in several homes. The oblong cushions (circa 50x100 cm) were not only used indoors but also to sit on in the carriage on Sundays when going to church. This was a regular opportunity in the farming community to show off the family’s social status – preferably by using several finely woven or embroidered cushions in the open carriage.

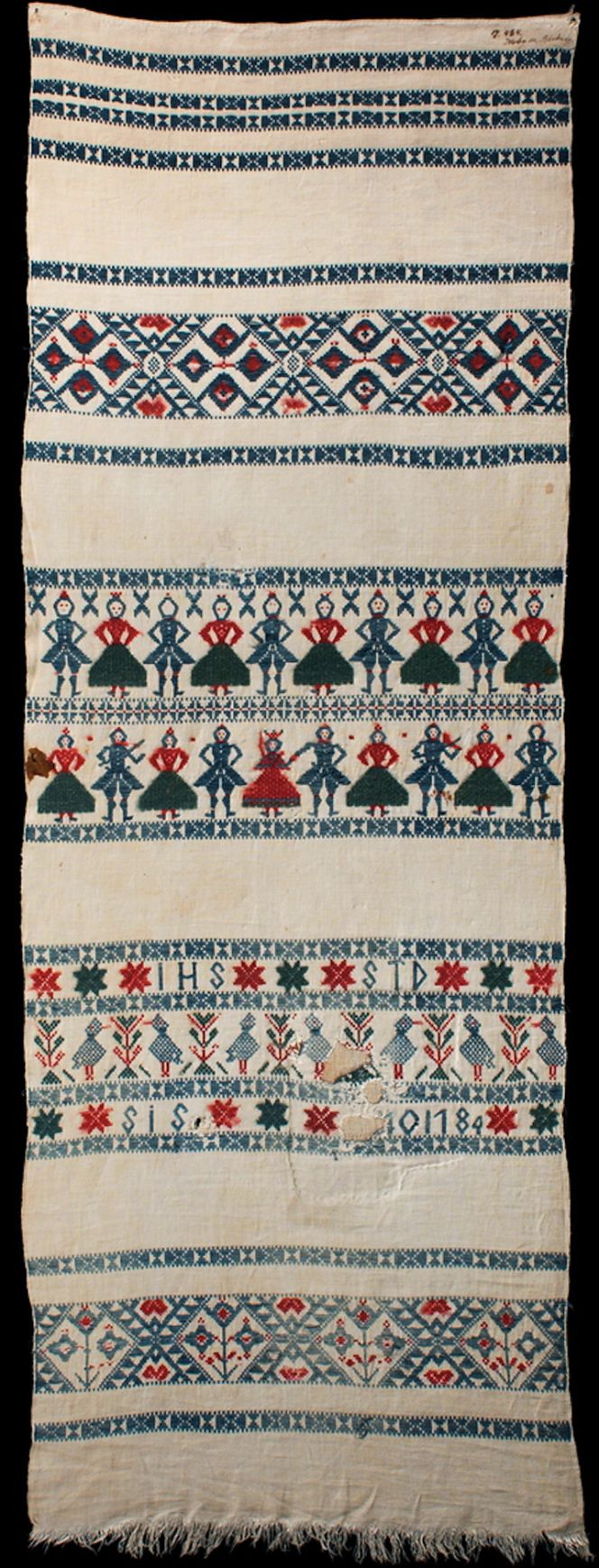

This vertically hanging linen cloth is typical in style for the decades around 1800; it was made/dated ‘1784’. The fabric was handwoven with an unbleached linen warp, with the same linen thread used for the shuttled ground weft. Various intense colours of woollen yarns were chosen for the decorative motif borders – woven in the traditional techniques opphämta and krabbasnår. Bräkne district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0017484. DigitaltMuseum).

This vertically hanging linen cloth is typical in style for the decades around 1800; it was made/dated ‘1784’. The fabric was handwoven with an unbleached linen warp, with the same linen thread used for the shuttled ground weft. Various intense colours of woollen yarns were chosen for the decorative motif borders – woven in the traditional techniques opphämta and krabbasnår. Bräkne district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0017484. DigitaltMuseum).Wall decorations

Covering the walls and sloping ceiling sections indoors with decorative textiles during feasts and festivals was a long-lasting tradition in the Blekinge province. First and foremost, with a linen cloth, often measuring circa 60x150 cm, art-woven in various colours and techniques on a white plain weaved linen ground, illustrated above (also painted examples existed, not included in this research). The preferred woven patterns were stars, roses, human figures, boats, horses and ornamental borders.

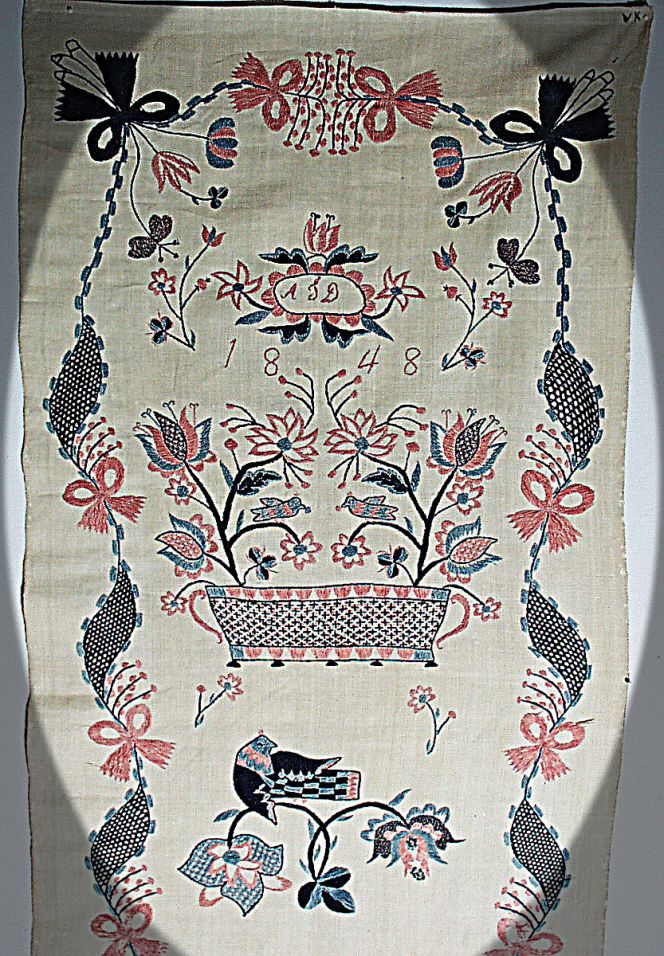

In contrast to the woven wall-hanging illustrated and described above, this example from the same province was embroidered in the so-called ‘Blekingesöm’ with cotton threads on plain woven linen dated in stitches with the year 1848. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0232890, part of the textile. DigitaltMuseum).

In contrast to the woven wall-hanging illustrated and described above, this example from the same province was embroidered in the so-called ‘Blekingesöm’ with cotton threads on plain woven linen dated in stitches with the year 1848. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0232890, part of the textile. DigitaltMuseum).This later developed type was instead embroidered in the Blekingesöm, a free embroidery style in pink, red, yellow, light- and dark-blue cotton thread stitched on white linen, which seems to have been inspired by East Indian fabrics and porcelain. While this stitching design is considered to have been introduced in the 1780s within vicarage families in the Blekinge province, East Indian influences can probably be considered. The Swedish East India Company (1731-1813) had been trading for more than 50 years at this time and had had good opportunities to sell/spread their goods to influential groups of the society – from the kings and nobles, wealthy bourgeois, priesthood and comfortable farmers. Furthermore, the combination of stitching, advanced design of the motifs and large-size embroideries demanded a trained hand, and this often meant professional female embroiderers who stitched these decorative interior textiles, searching their presumptive costumers by walking around to farmer’s homes, townhouses, etc.

‘Interior with people from Blekinge’ is dated from 1780 to 1810. This depiction gives a glimpse of female textile work. Judging by her colourful hair ribbons, the young unmarried woman was spinning flax on a wheel while her mother or maybe grandmother made the spun yarn into skeins. It is also interesting to notice the three porcelain pieces on top of the cupboard, which probably were of East Indian origin, which are possible to purchase for comfortable living farmers in the Blekinge province. Oil on panel by Pehr Hilleström. (Image: Uppsala Auktionskammare, online. Unknown present owner).

‘Interior with people from Blekinge’ is dated from 1780 to 1810. This depiction gives a glimpse of female textile work. Judging by her colourful hair ribbons, the young unmarried woman was spinning flax on a wheel while her mother or maybe grandmother made the spun yarn into skeins. It is also interesting to notice the three porcelain pieces on top of the cupboard, which probably were of East Indian origin, which are possible to purchase for comfortable living farmers in the Blekinge province. Oil on panel by Pehr Hilleström. (Image: Uppsala Auktionskammare, online. Unknown present owner).The embroidery design, as well as the art-woven hangings, were extremely popular – with a peak around the 1790s to 1840s at a time when a family, according to the estate inventories, could own up to sixty such wall decorations. To exemplify the popularity of these decorative linen textiles, see district, year of estate inventory and how many examples were listed in this particular year;

- Bräkne district | 1810 | 721 examples

- Bräkne district | 1830 | 520 examples

- Medelstad district | 1790 | 638 examples

- Medelstad district | 1810 | 707 examples

- Medelstad district | 1830 | 623 examples

Furthermore, a substantial number of such beautiful and decorative textiles have been preserved up to the present in museum collections and private homes alike. Wall hangings were primarily part of yearly or occasional festive traditions and, due to these circumstances, were placed for safekeeping in chests and drawers during most of the year, protected from sunlight, dust, and general wear and tear.

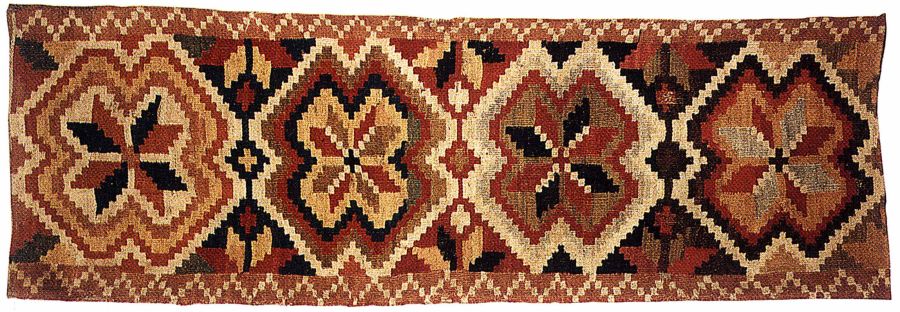

The bench cover is woven in double-interlocked tapestry – rölakan, with a typical ‘star in eight-petalled rose’ design for this geographical area. (Collection: Karlshamn Museum, Sweden. No. 2625). Photo: The IK Foundation.

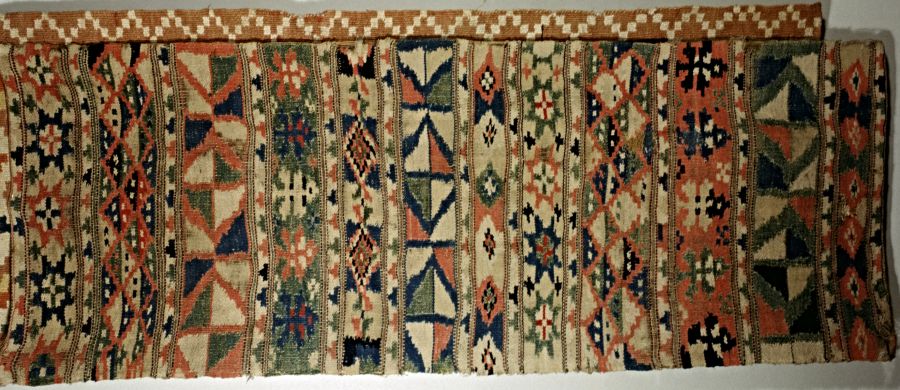

The bench cover is woven in double-interlocked tapestry – rölakan, with a typical ‘star in eight-petalled rose’ design for this geographical area. (Collection: Karlshamn Museum, Sweden. No. 2625). Photo: The IK Foundation. The second example is a bench cover woven in double-interlocked tapestry – rölakan from Blekinge province. The design comprised narrow T-borders and varied geometrical- and star motifs for the broader borders. (Collection: Karlshamns Museum, Sweden. No: 12059). Photo: The IK Foundation.

The second example is a bench cover woven in double-interlocked tapestry – rölakan from Blekinge province. The design comprised narrow T-borders and varied geometrical- and star motifs for the broader borders. (Collection: Karlshamns Museum, Sweden. No: 12059). Photo: The IK Foundation.Beds and textiles

The bed was the most essential piece of furniture for showing off textile treasures of the home, including mattresses, bedticks, oblong cushions, pillowcases, linen sheets, quilted bedcovers, knotted pile weaves, decorative bedcovers in art-woven techniques and curtain arrangements around the bedstead. Some textiles were necessary for warmth and comfort; others were made of luxurious patterned silks or finest linen with embroideries. The variations were plentiful depending on the family’s position in society – even if similarities can be glimpsed via the estate inventories of the nobility, bourgeois, priests, farmers and fishermen. Even so, the most basic comforts were not a reality for everyone.

According to the estate inventory listings, it was not particularly common before 1830 to use some sort of mattress; in many such cases, it was probable that one slept straight on a layer of straw or hay. However, when long pads or mattresses were placed at the bottom of the bed, these were filled with various materials to be as comfortable as possible, like straw, hay, grass, feather and down. Featherbeds stuffed with feathers or down or a mix of both were foremost used in more well-to-do homes due to their unsurpassable qualities of warmth and comfort. More easily accessible materials such as straw and grass had to be changed now and then to give a good night’s sleep. Another textile group consisted of various pillows – used for resting one’s head on and serving as decorative features during the day. Such ordinary pillows were standard; just like the mattresses, these were stuffed with a wide range of materials depending on one’s means. For instance, in the Listers district in 1810, 336 examples were listed; in the Östra district the same year, 356 models and in the Medelstad district in 1850, 506 pillows for beds were registered. Some were woollen striped in multiple colours, whilst other such cases were of white linen decorated with monograms and edged with lacework. Most estate inventories reveal little details about exactly how each pillow was made. Still, at times, weaving techniques, patterning, materials, embroidery style and, in particular, local names give some clues. However, such a description is often an obstacle, being hard to translate to modern Swedish terms and almost impossible to translate into English.

Linen sheets were not used daily in most homes but were added for decoration only, with visible embroideries and lacework on the top sheet during festivities and special occasions. The estate inventories listed hundreds of such linen sheets during each researched year, the most significant number in the Medelstad district in 1850, with 916 examples. The qualities of these linens varied greatly, which affected the valuation, with the very finest sort valued five times higher than the coarsest linen-tow quality. The bourgeois also owned substantially more significant quantities of linen sheets than other groups in society, counting up to 150 in one family alone. The more comfortable farmers’ homes usually only listed 10-20 linen sheets. The wealthy Christian Albrekt in Karlskrona, whose estate inventory was dated 15 March 1830, gives an idea of this sort of bedlinen. He owned 84 linen sheets, divided into qualities – finest linen, hemp, cotton, and linen-tow. To have cotton sheets in one’s store in 1830s Sweden was regarded as extra special, whilst cotton still was expensive and, in particular, when used for such large fabrics as bed sheets.

Bedcover woven in ‘opphämta’ on an unbleached linen warp, with a weft of coloured woollens for ornamentation on a linen shuttled ground. Notice the middle seam on the bedcover; this was due to the relatively narrow looms, which made it necessary to weave two identical but reversed pieces to get the required width of a bedcover. Early 19th century Medelstad district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0120250. DigitaltMuseum).

Bedcover woven in ‘opphämta’ on an unbleached linen warp, with a weft of coloured woollens for ornamentation on a linen shuttled ground. Notice the middle seam on the bedcover; this was due to the relatively narrow looms, which made it necessary to weave two identical but reversed pieces to get the required width of a bedcover. Early 19th century Medelstad district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0120250. DigitaltMuseum).The estate inventories listed a great variety of warming and decorative bedcovers, striped bedticks, knotted pile weaves, quilts, silk covers, etc. Overall, it is evident that the individuals who wrote these documents had more knowledge about techniques and local names of bedcovers than about many other textile types. To start with the knotted pile weaves, the wool pile was often made in brownish and grey and used as a warming bedcover long before 1770. The technique was common in the whole province of Blekinge and was rich in numbers from 1790 to 1830. In the Lister district in 1810, for instance, many homes owned two or three such bedcover-sized textiles while owning eight to ten knotted pile weaves also existed. Textile material combined with fur or leather was also used for beds. The most warming double layered designs were to use a bedcover woven in an art-woven woollen technique like double-interlocked tapestries or weft-patterned techniques krabbasnår, halvkrabba, dukagång, opphämta or munkabälte, and to fasten this fabric on to sheep fells stitched together to the required size. Another essential and even more common textile for warmth in the bed included the striped woollen feather-filled bedticks – or materials like hay or straw could also be used as filling. Such textiles were owned in the most significant number from 1790 to 1850 when most homes included two or three examples, whilst the most numerous had ten to twelve bedticks in their textile stores and beds.

To a lesser extent, tapestry woven bedcovers were listed, too, but only two or three were owned by the same home. However, many of these textiles were just mentioned as ‘bedcovers’ simultaneously as some estate inventories reveal details of the more unusual designs. First and foremost, bedcovers originating from the province of Västergötland, that is to say, these objects, just as many other desirable textiles, had been purchased via itinerant pedlars who spread their products across the whole country. These bedcovers were often woven into the weft-patterned technique opphämta and had a relatively high value. Lined patchwork quilts, quilted linen and cotton designs, silk bedcovers and printed calico models were other bedcovers listed in the estate inventories – from the bourgeoise and other well-to-do homes, in particular from families living in the cities of Karlskrona and Ronneby. The ownership often stretched to only two or three such bedcovers, but postmaster Lagström in Ronneby had fourteen quilted bedcovers at his demise in 1850.

On the other hand, the farmers' homes owned bed curtains for their bedstead to a greater extent than other groups in society. This is based on the research of estate inventories, particularly from 1810 to 1850, especially in the Lister and Bräkne districts. Usually, each home only owned one set of such decorative and warming bed curtains, but the more comfortable farmers could have three of four sets in their possession.

Notice: This is the first essay of two about the textile history of the Blekinge province in Sweden from 1770-1870. The second part will be presented in the following forthcoming essay. See the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen (1998, pp. 131-149) for the complete list of all textile categories and conclusions via the research of 1313 estate inventories from the four districts and Karlskrona in Blekinge province registered during the years 1770, 1790, 1810, 1830, 1850 and 1870.

Sources:

- DigitaltMuseum/Creative Commons. See the reference in four of the captions).

- Fischer, Ernst, ‘Två blekingska flamskvävnader och deras nordiska fränder’, Blekingeboken 1965.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Rölakan i Blekinge’, Blekingeboken 1991.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets konst och kulturhistoira, Christinehof 1992.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Textilt överflöd från gamla blekingska hem – En textilhistorisk undersökning av bouppteckningar 1770-1870’, Blekingeboken 1998, [pp. 131-149].

- Henschen Ingegerd, ‘En grupp hängkläden från Nättraby’, Blekingeboken 1937.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969.

- Landsarkivet i Lund, Sweden (Regional State Archive in Lund). In-depth research in 1990-91 of estate inventories, dating 1770-1870).

- Sylwan, Vivi, Svenska ryor, Stockholm 1934.

- Thorman, Elisabeth, ‘Hemslöjd från Blekinge i föreningen för svensk hemslöjd’, Hemslöjden 1941.

- Walterstorff, Emelie von, Textilt Bildverk, Stockholm 1925.

- Walterstorff, Emelie von, Svenska vävnadstekniker och mönstertyper, Stockholm 1940.

- Zickerman, Lilli, Sveriges folkliga textilkonst, Stockholm 1937.

- Zickerman, Lilli, Om den blekingska slöjden, Karlshamn 1913.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE