ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

TEXTILES IN SWEDISH HOMES (part 2)

– A Documentation of Estate Inventories in the Blekinge Province: 1770 to 1870

Table linen, towels, mats, carpets and curtains will be the focus of this second two-part essay, based on a wide selection of transcribed Swedish estate inventories from the province Blekinge during the years 1770, 1790, 1810, 1830, 1850 and 1870. Paintings, photographs and preserved textile treasures also assist this documentation. A total of 1313 such inventories have been part of my in-depth research – giving evidence of ownership, traditional stores based on extensive dowries and fashion trends over these hundred years. Poverty and wealth co-occur over the written pages via possessions in these many country and city homes, listing everything from one bedcover to hundreds of objects. However, it is essential to remember that 15-20% of such documents did not include furnishing textiles, and many of the poor did not have an estate inventory made up after their death.

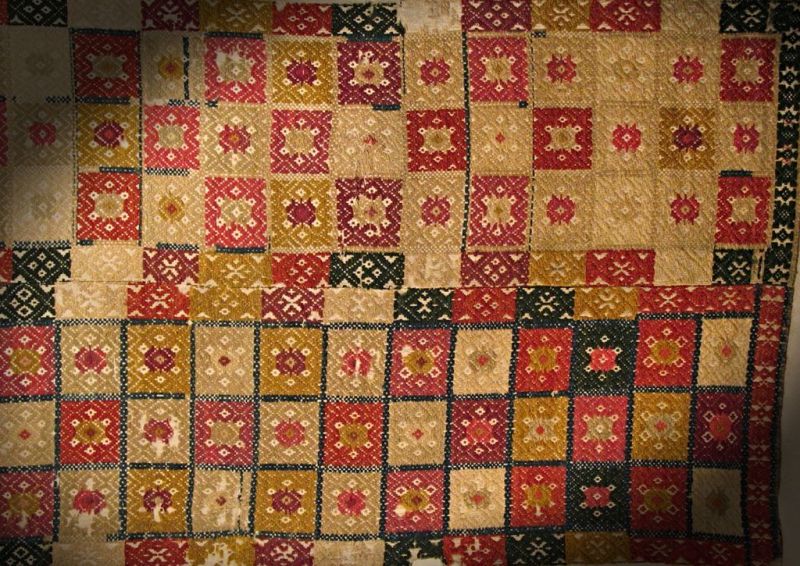

This bedcover was woven in the early 19th century – in weft-motif tabby type ‘opphämta’ on an unbleached linen warp, with coloured woollens for ornamentation and linen ground in the weft. The motifs close-up to the middle seam used to fit well on such fabrics, whilst the weaver produced two identical but reversed pieces on the relatively narrow handlooms. However, these ornamentations and colours fit poorly in this seam, indicating that it was initially woven for a long bench and later cut in half and stitched together. Such a bedcover could also be used as table decoration. |Lister district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0068443. DigitaltMuseum).

This bedcover was woven in the early 19th century – in weft-motif tabby type ‘opphämta’ on an unbleached linen warp, with coloured woollens for ornamentation and linen ground in the weft. The motifs close-up to the middle seam used to fit well on such fabrics, whilst the weaver produced two identical but reversed pieces on the relatively narrow handlooms. However, these ornamentations and colours fit poorly in this seam, indicating that it was initially woven for a long bench and later cut in half and stitched together. Such a bedcover could also be used as table decoration. |Lister district, Blekinge province. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0068443. DigitaltMuseum).Finely woven table linen in the form of tablecloths and napkins was primarily used during festivities and special occasions, with some exceptions for well-to-do bourgeois homes at the end of this period. The coarser linen-tow cloths were often preferred for everyday use, whilst tablecloths were lacking from day-to-day use in many homes. Judging by the estate inventories and preserved textiles up to the present, various linen qualities were most common. Still, so-called half-woollen qualities existed, too, either woven with a linen or cotton warp and wool for the weft. Weaving techniques listed for all such furnishing textiles were damask, diaper, lozenge twill and several other variations of twill qualities. The most significant number of tablecloths was kept in the burghers’ and bourgeois’ homes in the cities of Ronneby in the Medelstad district and Karlskrona. For instance, from the estate inventories of Karlskrona city in 1830, the listed homes owned 1226 napkins – of which 477 were in one household alone. While single, well-to-do dwellings in this city usually held circa thirty linen tablecloths. All this linen, however, was not home-woven or locally produced handicraft; the Swedish linen manufacturers played a vital role in these fine textiles. The most well-known were Flor’s Linen Manufacturer in Hälsingland and Vadstena Linen Manufacturer. Additionally, it is interesting to note that the farming community traditionally used woven bedcovers as table decorations during festivities. During the 19th century, the small embellishing cloth placed in the middle of a large table became increasingly popular; the large linen napkins could also serve this purpose.

‘Convivial Scene in a Peasant's Cottage’ – oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström dated circa 1780 to 1810. This depiction probably illustrated a Sunday come-together in the neighbouring province Skåne, but the similarities linked to home interiors were many with Blekinge. The focus here will be the fine linen tablecloth, which had comparable uses, social status and desirability in Sweden's two southerly provinces. Tablecloths were also one of the largest groups of textiles registered in the Blekinge estate inventories, from two or three such fabrics to more than 30 examples in the same home, often combined with an even more significant number of linen napkins. Both textile categories were essential parts of the young woman’s textile dowry among the comfortable living farmers. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. NM 966. Wikimedia Commons).

‘Convivial Scene in a Peasant's Cottage’ – oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström dated circa 1780 to 1810. This depiction probably illustrated a Sunday come-together in the neighbouring province Skåne, but the similarities linked to home interiors were many with Blekinge. The focus here will be the fine linen tablecloth, which had comparable uses, social status and desirability in Sweden's two southerly provinces. Tablecloths were also one of the largest groups of textiles registered in the Blekinge estate inventories, from two or three such fabrics to more than 30 examples in the same home, often combined with an even more significant number of linen napkins. Both textile categories were essential parts of the young woman’s textile dowry among the comfortable living farmers. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. NM 966. Wikimedia Commons).The linen towel has a somewhat mixed history, giving several possibilities for use for such listed objects in the estate inventories. Firstly, the towel is traditionally connected to table manners in well-to-do homes, when the dining person is served a towel after washing his or her hands. The second usage of towels during this period was linked to wall decorations in the farming community, whilst a third option was as an “ordinary” towel, which was placed on a hook or behind a protective cover beside a basin. Towels were listed in all districts, the most significant number in the Medelstad district in 1850, with a total of 403 examples. This included the well-to-do postmaster Lagström in the city of Ronneby, who had 108 towels at the time of his death. Judging by his position in society as well as the period in time, all these towels were probably referred to as linen towels for drying your hands or for kitchen use. On the other hand, when the estate inventories already in the year 1770 listed towels in farmers’ homes, one must assume or even conclude that these textiles referenced decorative features for the walls.

This fabric sample was handwoven around the year 1875 or somewhat earlier in the Medelstad district in the Blekinge province. The choice of colours and the so-called monk’s belt technique were traditionally used for towels, tablecloths, etc., in this geographical area. | Collected by Lilli Zickerman (1858-1949). (Courtesy: Malmö Museums, Sweden. MM 026680).

This fabric sample was handwoven around the year 1875 or somewhat earlier in the Medelstad district in the Blekinge province. The choice of colours and the so-called monk’s belt technique were traditionally used for towels, tablecloths, etc., in this geographical area. | Collected by Lilli Zickerman (1858-1949). (Courtesy: Malmö Museums, Sweden. MM 026680).Mats and carpets were not part of the textile furnishing in most homes during the hundred years (1770-1870); this custom even included the more well-situated burghers and bourgeois who lived in the cities. Overall, the estate inventories only listed sporadic floor decorations, with only forty mats/carpets in 1313 such documents. Most of these appeared as late as 1870 and were located in the most easterly district, Östra and the city of Karlskrona. Judging by my research, it is doubtful that rugs woven with a linen or cotton warp with rags as weft had been introduced at this time in the province. This type of rag rug became popular in Sweden from the 1860s to 1890s, and due to this fashion, more and more homes started to use textiles on the floor. Before this period, the tradition on Sundays and during festivities was to strew straw, chopped spruce twigs, or sand on the floorboards. The most important reason for not using rag rugs on the floor prior to this period was that scraps of fabric of all kinds had a financial value and that rags were an essential ingredient in the manufacture of good-quality paper in pre-industrial times. This continued until the last decades of the 19th century, when wood fibre was increasingly used instead, though often with inferior results.

Cottage interior in the Blekinge province, by the locally born painter Bengt Nordenberg (1822-1902), who was known for his genre painting in the Düsseldorf school style, a place where he had received some of his education. This interior probably dates back to the 1860s or 1870s, proving that a translucent cotton or linen curtain was used in the country home’s daily room. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0068261 (Black and white photograph of oil on canvas. DigitaltMuseum).

Cottage interior in the Blekinge province, by the locally born painter Bengt Nordenberg (1822-1902), who was known for his genre painting in the Düsseldorf school style, a place where he had received some of his education. This interior probably dates back to the 1860s or 1870s, proving that a translucent cotton or linen curtain was used in the country home’s daily room. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0068261 (Black and white photograph of oil on canvas. DigitaltMuseum).In contrast to mats and carpets, in smaller numbers, curtains were already included in estate inventories from the early 19th century or, more rarely, even before this period. Well-to-do homes of the bourgeois and farmers dominated in such listings, but smaller crofters could also own one or two pairs of curtains. The most considerable amount of this textile group was included in 1850 when more than 100 pairs were listed in each district, and precisely in which type of designs and of what materials these ‘window curtains’ were made probably changed slightly over time. However, the translucent model of cotton or linen illustrated in the image above was one of the most common and preferred styles. Other arrangements let the fabric hang with one length on both sides of the window, either touching the window sill or of a floor-length model. Fine cotton qualities became increasingly popular when this material became less expensive around the mid-century. Furthermore, hanging gauzy delicate cotton curtains in as many windows as possible seems to have been a favoured way to show off textile abundance for neighbours and others passing by during this period.

This early photograph gives an interesting glimpse of city life in Karlskrona during the 1870s. The mixed architecture on the centrally located ‘Hantverkaregatan’ has a mixture of stone-built houses with iron balconies, side by side with one, two, or three-storied wooden houses. Curtains can be dimly seen in some of the windows. Otherwise, we know little about these particular interiors and used textile furnishing. However, this was a time of great changes; one of the most obvious in this city must have been the arrival of the railway in 1874. (Courtesy: Marine Museum, Karlskrona, Sweden. MM06444. Unknown photographer. DigitaltMuseum).

This early photograph gives an interesting glimpse of city life in Karlskrona during the 1870s. The mixed architecture on the centrally located ‘Hantverkaregatan’ has a mixture of stone-built houses with iron balconies, side by side with one, two, or three-storied wooden houses. Curtains can be dimly seen in some of the windows. Otherwise, we know little about these particular interiors and used textile furnishing. However, this was a time of great changes; one of the most obvious in this city must have been the arrival of the railway in 1874. (Courtesy: Marine Museum, Karlskrona, Sweden. MM06444. Unknown photographer. DigitaltMuseum).To give further examples of textile ownership via these researched documents, a selection of individual estate inventories from my Swedish article (Hansen, 1998) will be listed in translation below.

Lister district

320 estate inventories were included from this geographical area:

- 1790, 13 July, the farm tenant Anders Karlsson in Agerum – 24 textile objects. | 1 bedtick, 3 cushions, 3 oblong cushions, 1 travel cushion, 5 bench covers, 1 pillow, 4 textile wall hangings, 2 knotted pile weaves, 3 linen sheets and 1 table cloth.

- 1850, 19 July, farmer’s wife Hanna Jönsdotter, Björkefalla – 90 textile objects. | 17 bedticks, 19 cushions, 3 bench covers, 3 bedcovers, 1 mattress, 5 textile wall hangings, 2 knotted pile weaves, 11 linen sheets, 6 tablecloths. 20 curtains and 3 other textiles.

Bräkne district

250 estate inventories were included from this geographical area:

- 1809, 17 April, farmer Jöns Pettersson, Hannamåla – 162 textile objects. | 12 bedticks, 2 oblong cushions, 1 travel cushion, 3 bench covers, 10 bedcovers, 15 pillows, 89 textile wall hangings, 3 art woven cushions, 1 quilted bedcover, 9 knotted pile weaves, 17 linen sheets, 11 table cloths and 4 textiles including leather.

- 1830, 2 January, seaman Nils Pehrsson, Evaryd – 1 textile object. | 1 knotted pile weave.

- 1869, 28 December, merchant’s wife Elna Olasdotter, Järnavik – 247 textile objects. | 6 bedticks, 13 cushions, 6 bench covers, 7 bedcovers, 6 pillows, 10 mattresses, 4 quilted bedcovers, 39 linen sheets, 16 pillowcases, 25 tablecloths, 3 textiles including leather, 23 curtains, 29 napkins, 51 towels, 8 carpets and 1 set of bed curtains.

Medelstad district

354 estate inventories were included from this geographical area:

- 1790, 11 March, farmer Pehr Trulsson, Hulta – 58 textile objects. | 3 bedticks, 8 cushions, 3 oblong cushions, 1 bench cover, 6 bedcovers, 3 pillows, 19 textile wall hangings, 2 art woven cushions, 1 art woven bedcover, 1 tapestry woven bedcover, 2 knotted pile weaves, 6 linen sheets and 3 tablecloths.

- 1849, 12 December, postmaster J. Lagström, Ronneby – 596 textile objects. | 6 bedticks, 29 cushions, 4 bedcovers, 5 mattresses, 14 quilted bedcovers, 116 linen sheets, 64 pillowcases, 33 tablecloths, 216 napkins, 108 towels and 1 other textile.

Östra district and the city of Karlskrona

351 respective 38 estate inventories were included from this geographical area and city of Karlskrona:

- 1789, 7 October, farmer’s wife Sissa Persdotter, Spjutsbygd – 118 textile objects. | 5 bedticks, 17 cushions, 1 oblong cushion, 3 bench covers, 3 bedcovers, 3 pillows, 33 textile wall hangings, 3 art woven bedcovers, 5 knotted pile weaves, 17 linen sheets, 4 tablecloths and 24 napkins.

- 1790, 29 February, farmer’s wife Ingjär Månsdotter, Björsmåla – 52 textile objects. | 2 bedticks, 4 cushions, 2 oblong cushions, 7 bedcovers, 17 textile wall hangings, 9 tapestry weaves, 2 knotted pile weaves, 7 linen sheets and 2 tablecloths.

- 1809, 28 November, boatswain Nils Fredag, Rörsmåla – 9 textile objects. | 1 cushion, 1 bedcover, 3 textile wall hangings, 3 knotted pile weaves and 1 linen sheet.

- 1830, 2 April, merchant Gustaf Corneer – Karlskrona – 883 textile objects. | 15 bedticks, 53 cushions, 16 bedcovers, 2 textile wall hangings, 104 linen sheets, 42 pillowcases, 34 tablecloths, 477 napkins and 140 tablecloths.

Notice: This is the second and final essay about the textile history of the Blekinge province in Sweden 1770-1870; the first essay was presented earlier in this month and included a map of the province. Please see the Swedish article (Hansen, 1998, pp. 131-149) for the complete list of all textile categories and conclusions via my research of 1313 estate inventories from the four districts and Karlskrona in Blekinge province registered during the years 1770, 1790, 1810, 1830, 1850 and 1870.

Sources:

- Fischer, Ernst, ‘Två blekingska flamskvävnader och deras nordiska fränder’, Blekingeboken 1965.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Rölakan i Blekinge’, Blekingeboken 1991.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets konst och kulturhistoira, Christinehof 1992.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Textilt överflöd från gamla blekingska hem – En textilhistorisk undersökning av bouppteckningar 1770-1870’, Blekingeboken 1998 [pp. 131-149].

- Henschen Ingegerd, ‘En grupp hängkläden från Nättraby’, Blekingeboken 1937.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969.

- Landsarkivet i Lund, Sweden (Regional State Archive in Lund). | Research in 1990-91 of estate inventories, dating 1770-1870.

- Sylwan, Vivi, Svenska ryor, Stockholm 1934.

- Thorman, Elisabeth, ‘Hemslöjd från Blekinge i föreningen för svensk hemslöjd’, Hemslöjden 1941.

- Walterstorff, Emelie von, Textilt Bildverk, Stockholm 1925.

- Walterstorff, Emelie von, Svenska vävnadstekniker och mönstertyper, Stockholm 1940.

- Zickerman, Lilli, Sveriges folkliga textilkonst, Stockholm 1937.

- Zickerman, Lilli, Om den blekingska slöjden, Karlshamn 1913.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE