ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

TEXTILES, TEA AND CINNAMON

– Observations of East India Trade by 18th Century Travelling Naturalists

Tea and textiles were particularly important categories within the complex East India trade, whilst cinnamon was one of many popular spices. These traded wares, together with a multitude of other luxury objects, were carefully chosen in the most profitable ratios for the ship-loaded goods – on the outward bound and return journey alike. This essay will look closer at Canton and Ceylon via travel journals written by the naturalists Pehr Osbeck and Carl Peter Thunberg during East India Company voyages between 1750 and 1779, together with Carl Linnaeus’ instruction ‘to get back a tea bush in a pot’ from his first travelling apostle, Christopher Tärnström in 1745. Besides the aim to study natural history to increase scientific knowledge, their journeys were partly financed via work as the ship’s chaplains respectively as an assistant ship’s surgeon for two such European trading companies. The observations of these former Linnaeus students give unique insights into everyday life, global cultures, and local communities along the routes intertwined by imperial expansions of the time.

![When these Swedish naturalists made observations in southeast Asia, the British trading company: the East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), had already traded in the area for 150 years; together with the Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese and others much earlier in time. The trade took many different directions. For instance, the Chinese had strict control of their trade and from the start of the early 17th century allowed the Europeans to come to one harbour only, Canton [today Guangzhou], where they had to trade after local rules. China was a powerful country with a large population, meaning that trading and all local commercial enterprises were either made on their terms or during equal conditions. This was immediately profitable for the Chinese, but equally so for the Europeans, but first when they sold the goods in Europe or via trading along the sailing route. In opposite to a Spice Island like Ceylon [today Sri Lanka], where the Dutch rather easily had taken control of the island – cinnamon among other spices could be harvested, transported and sold in the most profitable way possible from the perspective of the Dutch company. They usually met small resistance at arrival on the islands and if not, such an area was ruthlessly conquered and local inhabitants became enslaved or had to work for their new masters. Judging by a wide array of research and preserved historical documents, the Dutch likewise as other Europeans, took advantage if they saw a future potential wherever they anchored, which became an important part of the overseas expansion. (Map of Asia, ca 1770 by Jean Janvier (1746-76). Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-1770-800x560.jpg) When these Swedish naturalists made observations in southeast Asia, the British trading company: the East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), had already traded in the area for 150 years; together with the Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese and others much earlier in time. The trade took many different directions. For instance, the Chinese had strict control of their trade and from the start of the early 17th century allowed the Europeans to come to one harbour only, Canton [today Guangzhou], where they had to trade after local rules. China was a powerful country with a large population, meaning that trading and all local commercial enterprises were either made on their terms or during equal conditions. This was immediately profitable for the Chinese, but equally so for the Europeans, but first when they sold the goods in Europe or via trading along the sailing route. In opposite to a Spice Island like Ceylon [today Sri Lanka], where the Dutch rather easily had taken control of the island – cinnamon among other spices could be harvested, transported and sold in the most profitable way possible from the perspective of the Dutch company. They usually met small resistance at arrival on the islands and if not, such an area was ruthlessly conquered and local inhabitants became enslaved or had to work for their new masters. Judging by a wide array of research and preserved historical documents, the Dutch likewise as other Europeans, took advantage if they saw a future potential wherever they anchored, which became an important part of the overseas expansion. (Map of Asia, ca 1770 by Jean Janvier (1746-76). Public Domain).

When these Swedish naturalists made observations in southeast Asia, the British trading company: the East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), had already traded in the area for 150 years; together with the Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese and others much earlier in time. The trade took many different directions. For instance, the Chinese had strict control of their trade and from the start of the early 17th century allowed the Europeans to come to one harbour only, Canton [today Guangzhou], where they had to trade after local rules. China was a powerful country with a large population, meaning that trading and all local commercial enterprises were either made on their terms or during equal conditions. This was immediately profitable for the Chinese, but equally so for the Europeans, but first when they sold the goods in Europe or via trading along the sailing route. In opposite to a Spice Island like Ceylon [today Sri Lanka], where the Dutch rather easily had taken control of the island – cinnamon among other spices could be harvested, transported and sold in the most profitable way possible from the perspective of the Dutch company. They usually met small resistance at arrival on the islands and if not, such an area was ruthlessly conquered and local inhabitants became enslaved or had to work for their new masters. Judging by a wide array of research and preserved historical documents, the Dutch likewise as other Europeans, took advantage if they saw a future potential wherever they anchored, which became an important part of the overseas expansion. (Map of Asia, ca 1770 by Jean Janvier (1746-76). Public Domain). The main reason why the various European East India Companies were financially successful was the purchase of raw silk, silk and cotton fabrics as well as tea, spices and porcelain. Those were desirable products which could be sold at a great profit back home or be exported on after each successful voyage. Most of the ships managed the long journey and returned to Europe with their valuable cargo, and so did the Prins Carl with the ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) on board in 1752. Research by the late historian Sven T. Kjellberg of the Swedish East India Company (first founded in 1731) also shows that the value of the textiles was relatively high, compared to that of porcelain, although the fabrics made up a smaller part of the cargo than the fragile china. There are many gaps in the papers still intact, and it can therefore not be determined from the time of Osbeck’s voyage, but silk, satin and cotton wares represented 8.2% of the value during the years 1762-1767, whereas tea represented 87% and porcelain 4.8%, respectively.

The large percentage of tea, may seem somewhat surprising, but the main reasons were that Chinese tea was profitable, a highly desired “exotic” product in several strata of society, reasonably easy to transport on a long-distance sailing ship and particularly because the main bulk of tightly packed tea chests were resold to other European traders at auctions in Göteborg.

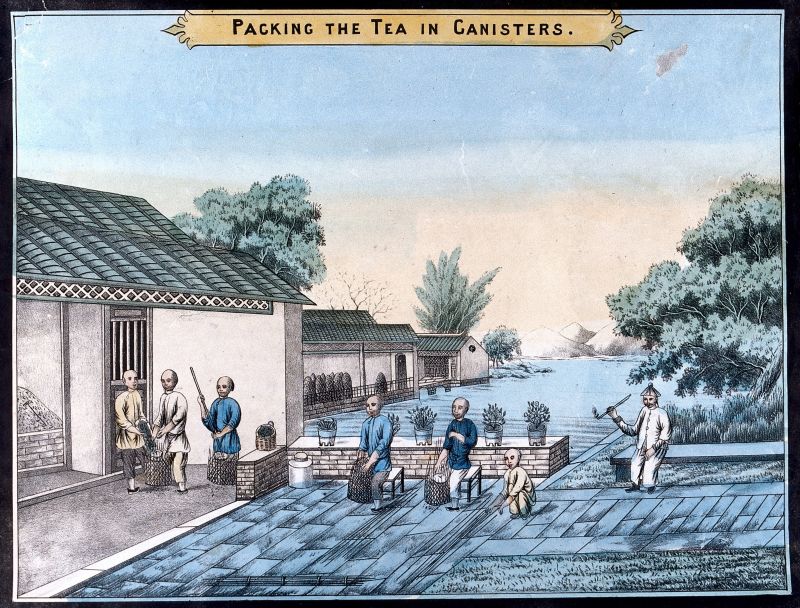

This coloured engraving of ‘A tea plantation in China: workers pack the tea into canisters for export’, dated to around 1800, but even so gives interesting details of such a procedure also earlier in time of the transportation of tea to Europe. The men are wearing working trousers and jackets – indigo dyed, light yellow or naturally white – probably made of cotton fabric. While such depicted basket shaped canisters were delivered to the supercargoes at the local merchants, close to the European factories in the harbour, to be quality checked before the tea was packed in chests. The finer sorts, could according to a travel journal from 1745-48 by the ship’s chaplain Israel Reinius (1727-1797), not be stamped and packed so hard together, as some coarser sorts. The finer tea as Pekoe, Congo and Souchong were due to this carefully packed in chests dressed with paper on the inside and at the top covered with a piece of cotton fabric for extra protection. The three tea sorts mentioned by Reinius were also part of the cargo on a Swedish East India Company ship of a few years later, which can be studied in great detail via Pehr Osbeck’s journal, listed below. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library: unnumbered. Creative Commons).

This coloured engraving of ‘A tea plantation in China: workers pack the tea into canisters for export’, dated to around 1800, but even so gives interesting details of such a procedure also earlier in time of the transportation of tea to Europe. The men are wearing working trousers and jackets – indigo dyed, light yellow or naturally white – probably made of cotton fabric. While such depicted basket shaped canisters were delivered to the supercargoes at the local merchants, close to the European factories in the harbour, to be quality checked before the tea was packed in chests. The finer sorts, could according to a travel journal from 1745-48 by the ship’s chaplain Israel Reinius (1727-1797), not be stamped and packed so hard together, as some coarser sorts. The finer tea as Pekoe, Congo and Souchong were due to this carefully packed in chests dressed with paper on the inside and at the top covered with a piece of cotton fabric for extra protection. The three tea sorts mentioned by Reinius were also part of the cargo on a Swedish East India Company ship of a few years later, which can be studied in great detail via Pehr Osbeck’s journal, listed below. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library: unnumbered. Creative Commons).On the first day of January 1752, the ship Prins Carl was fully packed and ready to head for Göteborg harbour in Sweden. Osbeck gave a detailed account of the weight, sort, and number of tea chests or canisters.

- ‘1,030,642 pounds of Bohea-tea, in 2885 chests.

- 96,589 lb. Congo-tea, in 1071 large, and 288 lesser chests.

- 67,388 lb. Soatchoun-tea, in 573 large and 1367 lesser chests.

- 17,205 lb. Pecko-tea, in 323 chests.

- 6,670 lb. Bing-tea, in 119 chests.

- 7,930 lb. of Hyson-Skinn-tea, in 140 chests.

- 2,206 lb. of Hyson-tea, in 31 tubs.

- 3,557 lb. of several sorts of tea, in 1720 canisters.

The ‘Silk Stuffs’ and ‘Porcelain’ were equally listed:

- ‘961 pieces Posies Damask.

- 67 ditto ditto of 2 colours.

- 143 ditto Upholstery Damask.

- 673 ditto Satins.

- 15 ditto ditto in 2 colours.

- 16 ditto with coloured bouquets.

- 681 ditto Paduasoys

- 192 ditto Grosgrains.

- 1291 ditto Taffetas.

- 16 ditto Lampas.

- 5319 ditto yellow Cotton Nankeens.

- 5047 lbs raw Silk in 33 chests.

- Porcelain: 222 chests, 70 tubs, 52 lesser chests, and 919 packs’.

Interesting comparisons to Osbeck’s list of silks are these samples of ’East Indian Gros de Tours, Gorgerons and taffetas’ – qualities which originated from the Swedish East India Company imports of fine silks – part of Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) educational collection, dated to circa 1736 to 1774. Plain coloured silks were named after weaving technique and fineness, often with a similar looking ribbed or plain structure. Taffetas for instance, was also carried on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in 1752, listed above in the large number of ‘1291 pieces’. Other single coloured silk qualities could be named as Gros de tour, Gorgerons, Paduasoy and plain Satins. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum. NM.0017648B:10 Digitalt Museum).

Interesting comparisons to Osbeck’s list of silks are these samples of ’East Indian Gros de Tours, Gorgerons and taffetas’ – qualities which originated from the Swedish East India Company imports of fine silks – part of Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) educational collection, dated to circa 1736 to 1774. Plain coloured silks were named after weaving technique and fineness, often with a similar looking ribbed or plain structure. Taffetas for instance, was also carried on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in 1752, listed above in the large number of ‘1291 pieces’. Other single coloured silk qualities could be named as Gros de tour, Gorgerons, Paduasoy and plain Satins. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum. NM.0017648B:10 Digitalt Museum).Osbeck also mentioned a variety of goods in his journal the same day, including mother of pearl, rhubarb, painted papers, arrack and japanned wares. Together with supplies necessary for the voyage:

- ‘Having taken in our cargoe in porcelain, tea, silk, &c. according to the following account, and provided ourselves with water for our return as far as Java, we yet took in this day some Chinese potatoes, turnips, yams, carrots, leeks, cabbages, and other garden stuff.’

This portrait of Pehr Osbeck originates from his early years as rector in the parish of Hasslöv in southern Sweden, circa a decade after his East India voyage. Osbeck is portrayed wearing his everyday clerical garb, consisting of a long black frock-coat, which traditionally stretched over the shoulders and buttoned down the front, falling in neat pleats down the back. He most probably wore similar garb during his voyage in 1750 to 1752, when working as a ship’s chaplain and in passing even mentioned his clerical garments in the journal. (Courtesy: Portrait by Magnus Lindgren. Ownership: Hasslöv church, Sweden). Photo: The IK Foundation.

This portrait of Pehr Osbeck originates from his early years as rector in the parish of Hasslöv in southern Sweden, circa a decade after his East India voyage. Osbeck is portrayed wearing his everyday clerical garb, consisting of a long black frock-coat, which traditionally stretched over the shoulders and buttoned down the front, falling in neat pleats down the back. He most probably wore similar garb during his voyage in 1750 to 1752, when working as a ship’s chaplain and in passing even mentioned his clerical garments in the journal. (Courtesy: Portrait by Magnus Lindgren. Ownership: Hasslöv church, Sweden). Photo: The IK Foundation.Whilst Christopher Tärnström’s (1711-1746) instructions ahead of his voyage in 1745, on a Swedish India Company ship as a ship’s-chaplain-cum-naturalist contained among many others the following wish in Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) given Memorandum: ‘To get back a tea bush in a pot or at least seeds thereof, kept as he of me has received a verbal instruction’. A second Memorandum given by hand to Tärnström at his departure from Uppsala, towards the East India ship in Göteborg in December 1745, also gave further instruction from Linnaeus how to best conserve seeds from the tea plant. This included advice on various climates, seeds kept dry in waxed paper or cotton, and even some kept in fine sand, glass bottles and lead-sealed boxes. However, due to Tärnström’s untimely death before arriving to Canton and his diary lasting close up to his last days, 10 November in 1746 at Pulo Condore [today Côn Sơn Island], he never got the opportunity to describe or collect a tea bush. This can be compared with Pehr Osbeck’s attempts a few years later, on the day of his return from Canton, his diary included this anecdote on 4 January 1752: ‘Every one leaped for joy, and my Tea-shrub, which stood in a pot, fell upon the deck during the firing of the cannons, and was thrown overboard without my knowledge, after I had nursed and taken care of it a long while on board the ship…’ His interest in the subject was also enlightened, with detailed sophisticated descriptions of the traditions and ceremonies around tea, accompanied by a plate in his travel journal that gave information about various sorts of tea.

![Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) here depicted in full figure at his visit together with the Dutch Ambassador et al in Jedo/Edo [today Tokyo] in 1776, dressed in a braided galloon dress with sword. However, what sort of clothing he wore during his visit at Ceylon, two years later is unknown. (From: Copper plate, print of Carl Peter Thunberg).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5-carl-peter-thunberg-664x969.jpg) Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) here depicted in full figure at his visit together with the Dutch Ambassador et al in Jedo/Edo [today Tokyo] in 1776, dressed in a braided galloon dress with sword. However, what sort of clothing he wore during his visit at Ceylon, two years later is unknown. (From: Copper plate, print of Carl Peter Thunberg).

Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) here depicted in full figure at his visit together with the Dutch Ambassador et al in Jedo/Edo [today Tokyo] in 1776, dressed in a braided galloon dress with sword. However, what sort of clothing he wore during his visit at Ceylon, two years later is unknown. (From: Copper plate, print of Carl Peter Thunberg).Similarly, as Pehr Osbeck in China, Carl Peter Thunberg, one of Carl Linnaeus' later students born exactly 20 years after Osbeck, gave information in his journal about tea traditions, drinking of tea, harvesting, etc, when visiting Japan. On the other hand, trading for export of tea was almost non-existent in this country according to Thunberg’s observations: ‘Commerce in Japan’: The Tea Trade is confined entirely to the inland consumption, the quantity exported amounting to little or nothing.’

After his stay in Japan, Thunberg returned on the Dutch India Company ship to Batavia, where he spent about half a year, and on 5 July 1777, after many years abroad, the actual homeward journey began from Java and included a nearly six-month-long stopover on Ceylon. Both the capital Colombo and the provinces were observed during two round trips while he was staying on the island. Just like in Batavia, the Dutch directed the considerable trade in Colombo, mainly in cinnamon, coconut, arak, coffee and sundry spices. Those products were also mentioned by Thunberg, as were plants, animals and minerals, which he studied in his frequent fieldwork on the island.

This watercolour drawing date to circa 1596-1610, attributed to the draughtsman Elias Verhulst et al., clearly demonstrates the Dutch early interest and knowledge of natural history specimens from other continents – insects equally like plants, including cinnamon. To be compared with Carl Peter Thunberg, who made a very detailed information of the cinnamon trade during his voyage with the Dutch East India Company, during their stay at Ceylon about 175 years later in 1777. According to his journal, a local physician with great knowledge of local plants and medicine also assisted him during the stay on the island. Among many matters, he was informed about cinnamon which was traded via a complex network of merchants, ten qualities/sorts of cinnamon were noted, the importance of plantations as well as packing and sending the spice (described more closely below). However, the slavery on the island were only mentioned in brief by Thunberg and not in connection to the cinnamon trade, but instead from the angle of missionary aims or daily conveniences for the Europeans like when slaves carried a palm leave over the heads of people of distinction, for both Indians and Europeans instead of using ‘Parasols and Parapluyes’. (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Part of the drawing RP-T-BR-2017-1-7-37. Public Domain).

This watercolour drawing date to circa 1596-1610, attributed to the draughtsman Elias Verhulst et al., clearly demonstrates the Dutch early interest and knowledge of natural history specimens from other continents – insects equally like plants, including cinnamon. To be compared with Carl Peter Thunberg, who made a very detailed information of the cinnamon trade during his voyage with the Dutch East India Company, during their stay at Ceylon about 175 years later in 1777. According to his journal, a local physician with great knowledge of local plants and medicine also assisted him during the stay on the island. Among many matters, he was informed about cinnamon which was traded via a complex network of merchants, ten qualities/sorts of cinnamon were noted, the importance of plantations as well as packing and sending the spice (described more closely below). However, the slavery on the island were only mentioned in brief by Thunberg and not in connection to the cinnamon trade, but instead from the angle of missionary aims or daily conveniences for the Europeans like when slaves carried a palm leave over the heads of people of distinction, for both Indians and Europeans instead of using ‘Parasols and Parapluyes’. (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Part of the drawing RP-T-BR-2017-1-7-37. Public Domain).After some time in Colombo, Thunberg took part in a trip together with M. Frobus from the Dutch East India Company, whose task it was to supervise the packing of cinnamon in several places. The traveller followed carefully the activities of the Company but also had time to make observations of his own. During their round trip, the group spent nights in various houses built by the Company for the use of its employees when visiting plantations, for instance. The houses were often decorated with a variety of cloths and were described as follows in November 1777: ‘These were covered on the inside under the roof with linen, with which likewise the chairs as well as the table were covered on our arrival’. The visitors were similarly honoured with more decorative fabrics: ‘On our arrival before the house, a piece of linen was spread on the ground, and the palanquin set down upon it. After this, the linen was spread out for us to walk upon all the way to the house. This honour is commonly paid to Europeans, when they travel in the Company’s service and on its concerns’. Cinnamon appears to have been the top priority during the trip with M. Frobus; due to that, the group collected the spice in several places on their way to Mature. The following day, once they had safely arrived in the town, 326 sacks of cinnamon would be shipped off. The spice was packed in woollen sacks, which were not trading commodities in their own right, but (along with cow hides) intended as water and air tight sacks for the precious cinnamon exported to Europe via ship.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 114-118 & 278-279).

- Howgego, Raymond John, Encyclopedia of Exploration to 1800, Australia 2003.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974 (tea, porcelain and silk: pp. 211-257).

- Kungliga Biblioteket [National Library of Sweden], Stockholm (Manuscript: ’Tärnströms Instruktioner inför resan 1745’).

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Reinius, Israel, Journal hållen på resan till Canton 1745-1748…Helsingfors 1939.

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990 (pp. 182-183).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795 (Vol. IV).

- Tärnström, Christopher, Christopher Tärnströms journal – En resa mellan Europa och Sydostasien år 1746. Edited by Kristina Söderpalm, London & Whitby 2005 (pp. 222 & 224).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE