ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE CANTON TRADE IN SILK FABRICS

– A Swedish East India Company ship: 1750-1752

This second essay on an East India voyage will focus on the Chinese trade in silk textiles transported back to Sweden on a mid-18th century sailing from Canton via Surat on the outward leg. Silk in various colours and weaving techniques was overall the dominating textile category of the cargo on this East India ship. To put into proportion, the auctioned pieces of cotton stretched over two pages, whilst silk fabrics were listed on sixteen pages and silk for re-export from Göteborg on two pages in the sales catalogue. The in-depth study of the auction catalogue, which included a wide range of merchandise carried on Götha Leijon, aims to glimpse into this extensive commerce in the autumn of 1752. Several other primary sources further evidence the great demand for these desirable and expensive goods, in particular, learned via a reference book kept onboard, travel descriptions by two of Carl Linnaeus’ former students and preserved 18th century East India silk in Swedish collections.

‘A view of the Canton factories’ depicted by William Daniell circa 1805-10. This painting is a good comparison to the mid-18th century when the Swedish East India Company ship ‘Götha Leijon’ sailed when already eight factories were situated at this location. The Swedish factory can be seen behind the third flag, where all sorts of goods were collected prior to the return voyage to Sweden, including the many valuable fabrics, packed with special care in chests so as best to be protected against weather and wind as well as harmful creatures onboard during the long sea voyage. (Courtesy: Wikipedia, Public Domain).

‘A view of the Canton factories’ depicted by William Daniell circa 1805-10. This painting is a good comparison to the mid-18th century when the Swedish East India Company ship ‘Götha Leijon’ sailed when already eight factories were situated at this location. The Swedish factory can be seen behind the third flag, where all sorts of goods were collected prior to the return voyage to Sweden, including the many valuable fabrics, packed with special care in chests so as best to be protected against weather and wind as well as harmful creatures onboard during the long sea voyage. (Courtesy: Wikipedia, Public Domain). From the summary of wares on the second page of the sales catalogue of Götha Leijon, which took place at an auction in Göteborg on ‘the 17 August and the following days in the same year [1752]’, all silk fabrics are listed below in a translation to give an idea of the substantial number of fine qualities. Materials were mainly ordered during the stopover at Canton (Guangzhou).

- ‘1084 pieces of Paduasoy – Damask

- 67 ditto Paduasoy – Damask of two coloured

- 129 ditto Furnishing Damask

- 462 ditto Paduasoy

- 168 ditto flowery ditto

- 150 ditto Gorgerons

- 707 ditto Satins

- 15 ditto Lampas

- 1655 ditto Taffeta

- 20 ditto pattern-woven ditto

- 50 ditto striped ditto’

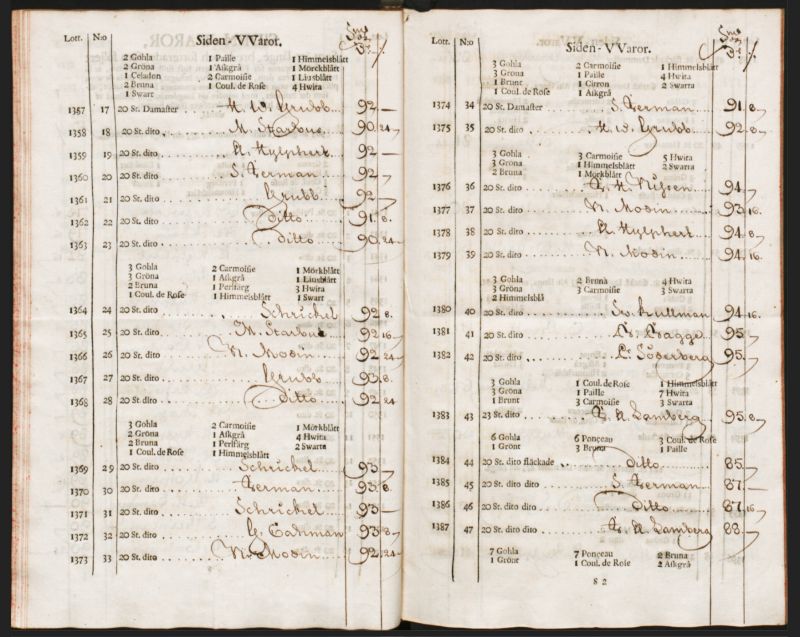

To give a few examples of individual lots, each quality of silk fabric was introduced to how many white, yellow, rose-coloured, sky-blue, dark blue, ash-grey, black, crimson, sherry, brown, etc., the auction had sold in August 1752. Followed by lot, the number of this particular group of goods, amount of pieces, the type of silk, the buyer's name and the price. On this page, damask was listed foremost, and some stained damasks sold somewhat cheaper. These sales catalogues have been preserved from 1733 to 1759. (Courtesy: ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive…The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue 1752, ’Götha Leijon’).

To give a few examples of individual lots, each quality of silk fabric was introduced to how many white, yellow, rose-coloured, sky-blue, dark blue, ash-grey, black, crimson, sherry, brown, etc., the auction had sold in August 1752. Followed by lot, the number of this particular group of goods, amount of pieces, the type of silk, the buyer's name and the price. On this page, damask was listed foremost, and some stained damasks sold somewhat cheaper. These sales catalogues have been preserved from 1733 to 1759. (Courtesy: ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive…The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue 1752, ’Götha Leijon’).The safe return of ‘Götha Leijon’ to Göteborg in the summer of 1752, with an extensive amount of silk fabrics, was one of the last ships that had that possibility during the coming decades. Future restrictions on such goods and the total import ban of silks in Sweden in 1756 made imports unlawful. Due to this, the Swedish East India Company ship, which returned in 1757, only carried silk for re-exportation and raw silk (to be used by the Swedish silk manufacturers). However, already in 1752, a considerable number of silk pieces were not acquired for the domestic market, whilst two pages were listed with: ’Silk goods for exportation, which will be kept secure by the customs lock and key, until they are re-exported.’ In this case, colours were carefully described together with all other acquired information for delicate damasks, taffetas, satins and lampas qualities.

Furthermore, besides these auction catalogues, the results of that commerce can be gleaned from travel journals, account books, share certificates, correspondence from the time, sporadically kept cash books, balance sheets etc., principally and most meticulously ascertained by Sven T. Kjellberg in his research and published in Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813 (The Swedish East India Companies 1731-1813). Interestingly, on the subject of imported silk, he presents a clear example of the various colours and techniques involved in those Chinese fabrics through transcription from an auction catalogue of 1736 after the voyage of the ship Fredericus Rex Sueciae.

- ‘942 pieces plain damask, 27 3⁄4, crimson, scarlet, jonquil, a yellow colour after the flower, dark blue, yellow, green, white, cherry, ash, brown.

- 480 pieces bi-coloured damask, 27 3⁄4, green-white, cherry-white, yellow-white, green-white, red-white, blue-white, scarlet-white, orange-white, thus a white ground all the way through.

- 44 pieces long damask, 31, white.

- 495 pieces of furnishing damask in 28 different designs, 28 crimson, scarlet, jonquil a yellow colour after the flower, light green, dark green, sky blue, yellow, light blue, green, dark blue.

- 703 pieces satin, 27 3⁄4, crimson, scarlet, light blue, dark blue, black, green, white, yellow, cherry, orange, brown.

- 120 pieces paduasoy, 28, black, sky blue, light blue, crimson, scarlet, green, cherry, orange, yellow, brown, ash.

- 100 pieces 8-threaded taffeta, 23 3⁄4, crimson, scarlet, cherry, green, yellow, light blue, white.

- 128 pieces 6-threaded taffeta, 23 3⁄4, crimson, scarlet, cherry, green, yellow, light blue, dark blue, black.’

It may be noted that many similarities in colours and fabric qualities can be observed via imported silk fabrics from Canton carried on the ship Götha Leijon sixteen years later, goods which, some weeks after the arrival in the home harbour Göteborg, were sold at auction during the late summer of 1752. Additionally, Kjellberg’s material shows that the value of the textiles was relatively high compared to that of porcelain, although the fabrics made up a minor part of the cargo than the fragile china with silk, satin and cotton wares represented 8.2% of the value during the years 1762-1767, whereas tea represented 87% and porcelain 4.8% respectively.

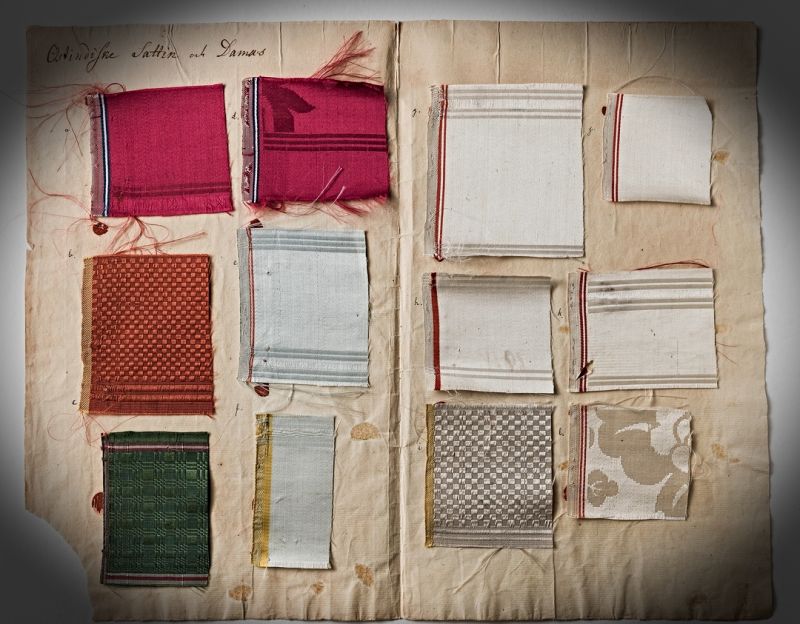

This selection of fabrics – named ’East Indian Satin and Damask’ – most likely originated from the Swedish East India Company imports, included in Anders Berch’s educational collection, circa 1736 to 1774, according to his years of work. For instance, the sample marked (a) was described as follows in the research by The Nordic Museum et al. (Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1991, p. 184). ‘Damask of 5-end satin. The motif is in weft effect against a background in warp effect. Selvage of basket weave and satin. Bands of different structure (end of piece)’. It is noticeable that damasks and satin samples are similar in colours and designs to silk qualities carried on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in 1752. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0017648b:11. DigitaltMuseum).

This selection of fabrics – named ’East Indian Satin and Damask’ – most likely originated from the Swedish East India Company imports, included in Anders Berch’s educational collection, circa 1736 to 1774, according to his years of work. For instance, the sample marked (a) was described as follows in the research by The Nordic Museum et al. (Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1991, p. 184). ‘Damask of 5-end satin. The motif is in weft effect against a background in warp effect. Selvage of basket weave and satin. Bands of different structure (end of piece)’. It is noticeable that damasks and satin samples are similar in colours and designs to silk qualities carried on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in 1752. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0017648b:11. DigitaltMuseum).The Swedish East India Company was one of the East India Companies in Europe, which made good profits from desirable goods in Canton, where the artisans worked in the artisans’ streets in specific quarters of the town. Among the numerous groups of artisans, the weavers formed a considerable number. In addition, a large group of people was occupied with the preparatory work of silk and cotton in the extensive production on the many looms. The naturalist and ship’s chaplain Olof Torén (1718-1753) on Götha Leijon described briefly from his stay that the cotton had to be spun, reeled, handed over to possible dyers, then warped, set up in the loom, made ready for weaving to the point at which the weaver took over. Silk went through a similar process, except for the spinning element which was missed out. The end of the silk thread was instead reeled directly from the cocoon, which contains approximately 1,000 metres of extremely fine thread. For very thin fabrics the silk from one single cocoon could make up the ready thread, but several cocoons were usually reeled simultaneously, resulting in a stronger but still very thin thread. All those facets required many skilful textile workers. However extensive and excellent the products of Canton may have been, the textiles produced at Nanking were better still. Nanking is situated some 1,000 kilometres northeast of Canton, and its goods were transported south by sea. Even the Cantonese themselves regarded the products made in Nanking as superior, which Torén interpreted as: ‘The Cantonese take great pains to make their goods strike the eye and sell well, but they do not take the same care to make them good and strong, nor do they offer them as the best and finest; for when they have a mind to praise their goods, they say that they come from Nanking, viz. Nanking silk, Nanking ink, Nanking fans, and even Nanking hams.’

This exquisite yellow silk atlas skirt with multicoloured silk embroidery demonstrates the demand not only for the materials in themselves but also for readymade garments, which originated from the Swedish East India Company trade in Canton. The design is made in a European-inspired style with popular rococo motifs. According to the Nordic Museum’s references, the delicate garment was interestingly enough brought back to Sweden by the East India Company captain Mathias Holmers during the 1750s and, together with other objects linked to 18th century Canton, sold to the museum in 1944. It is also highly probable that the exquisite garment had been carried back on an East India ship before the total import ban of silk fabrics in 1756 – even if the museum catalogue card gives the date 1758 for Holmer’s ownership. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0230805, part of the skirt, DigitaltMuseum).

This exquisite yellow silk atlas skirt with multicoloured silk embroidery demonstrates the demand not only for the materials in themselves but also for readymade garments, which originated from the Swedish East India Company trade in Canton. The design is made in a European-inspired style with popular rococo motifs. According to the Nordic Museum’s references, the delicate garment was interestingly enough brought back to Sweden by the East India Company captain Mathias Holmers during the 1750s and, together with other objects linked to 18th century Canton, sold to the museum in 1944. It is also highly probable that the exquisite garment had been carried back on an East India ship before the total import ban of silk fabrics in 1756 – even if the museum catalogue card gives the date 1758 for Holmer’s ownership. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0230805, part of the skirt, DigitaltMuseum).The naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805), ship’s chaplain on the Swedish East India Company’s sister ship Prins Carl also stayed in the Canton area and made several observations of the trade in silks around the same time as Olof Torén. Among other matters, Osbeck visited a weaving-mill in Canton (outside the city wall), where he noted that the Europeans ordered their fabrics on arrival in the city for them to be collected once ready shortly before their departure. It usually took the weaving-mill 90 days to weave, perhaps also treat the fabrics and deliver the goods. When the Company placed its order, it was decided what types of materials were wanted and in what qualities and colours and what quantity of each kind. The fabrics were packed by the Company’s own staff during dry and sunny days as the slightest moisture might endanger the sensitive materials, causing stains. After being quality-controlled and marked, the fabrics were rolled into bolts and packed in chests. A thin, fine Chinese paper covered the valuable cloths in the tightly packed chest, which was then nailed down and transported to the Factory. The fabrics were then stored there until the time of departure. In the trading stores, it was also possible to buy single pieces of woven cloth for the private use of the Chinese and the Europeans. That was best done ‘in the porcelain street, which is the broadest in the whole town...’ where one could buy silk fabrics, silk stockings, handkerchiefs, ribbons and cotton cloth in September 1751.

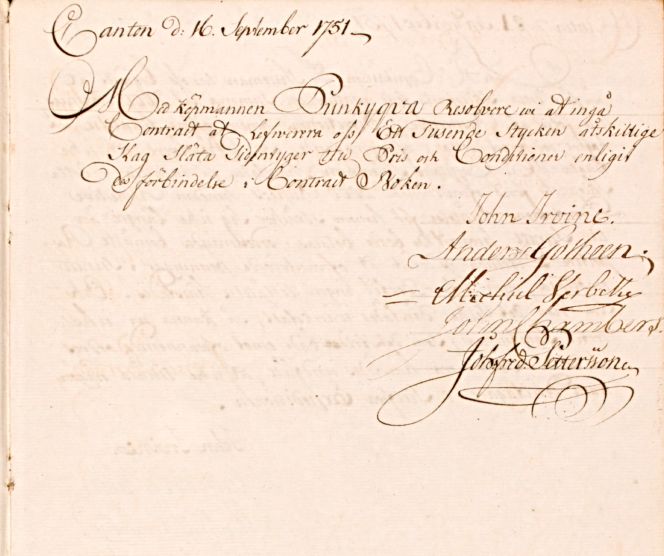

In conclusion of the trade in silk fabrics on this particular voyage by the Swedish East India Company in Canton– during the same month of 1751 as Pehr Osbeck mentioned what was generally offered for sale for the visiting Europeans – a large consignment was discussed in the ship’s reference book. It was signed by the supercargoes Anders Gotheen and John Chambers, together with three other individuals of commerce in the book, which included references and consultations onboard the ship ‘Götha Leijon’. In translation, the text says: ‘With the merchant Punkyqva, we Resolved to fulfil the Contract of delivery to us of One Thousand pieces of a great many sorts of Plain Silk Fabrics for a Price and Condition according to the obligations in the Contract Book. To my knowledge, however, the mentioned ‘Contract Book’ has not been preserved. Still, even so, this large number of fabrics purchased from one merchant alone gives a clue into how silk business was executed in Canton. (Courtesy: Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek…H 22:4A. ‘Rådplägningsbok för skeppet Götha Leijon' 1750-1752).

In conclusion of the trade in silk fabrics on this particular voyage by the Swedish East India Company in Canton– during the same month of 1751 as Pehr Osbeck mentioned what was generally offered for sale for the visiting Europeans – a large consignment was discussed in the ship’s reference book. It was signed by the supercargoes Anders Gotheen and John Chambers, together with three other individuals of commerce in the book, which included references and consultations onboard the ship ‘Götha Leijon’. In translation, the text says: ‘With the merchant Punkyqva, we Resolved to fulfil the Contract of delivery to us of One Thousand pieces of a great many sorts of Plain Silk Fabrics for a Price and Condition according to the obligations in the Contract Book. To my knowledge, however, the mentioned ‘Contract Book’ has not been preserved. Still, even so, this large number of fabrics purchased from one merchant alone gives a clue into how silk business was executed in Canton. (Courtesy: Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek…H 22:4A. ‘Rådplägningsbok för skeppet Götha Leijon' 1750-1752).From my experience, when studying 18th century documents, including all these hundreds of meters (listed in alnar ≈ ells ≈ 60cm) of East India silk, obviously such textiles have been preserved up to the present-day, primarily due to random and lucky circumstances. Even if many individuals took great care during their own life when all types of purchased cloth were expensive, garments often lasted for or were expected to last for a lifetime. Whilst most such fabrics were used for clothing and home furnishing, after some time or at least during the next generation if inherited, they had become worn-out or unfashionable. If still in good condition, such cloth was reused, remade, re-stitched, and later used as rags over the centuries. Some pieces, often of the most luxurious sorts, have been saved for various reasons, stored in attics or chests – and from the late 19th century and onwards, found their way to museums or are still being kept in private homes.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Notice: The first essay (January 23, 2023) of this two-part case study described the Surat trade in cotton textiles on the same voyage.

Original documents – in the form of auction catalogues, reference books and journals have been transcribed and translated from Swedish to English by the author of this essay. Digital sources mentioned below have been added with page numbers = digital page numbering. Specialist terms of fabric qualities have primarily been assisted by Sven T. Kjellberg’s in-depth research of the Swedish East India Company, and the author of this essay has also translated such terms. Several books and articles over the last decade – including the Swedish East India Company trade of these silk fabrics, their colours, demands over time, detailed statistical information etc. – have also been published. (Besides my monograph, Hansen 2017). Notable are (Hellman 2015), (Hodacs 2016), (Söderpalm 2016) and (Rönnbeck & Müller 2020) as listed in the sources.

Sources:

- Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek: Svenska ostindiska kompaniets arkiv. H 22:4A. ‘Rådplägningsbok för skeppet Götha Leijon' 1750-1752 (digitalised document).

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Volume Seven: Olof Torén’s journal in letter form).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 108-124 & 125-131. The chapters of Pehr Osbeck & Olof Torén: include textile observations from other perspectives too – linked to their voyages).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textilis Essays. ’18th Century East India Textile Trade – A Study of imported Merchandise to Sweden’: No: CIV | April 4, 2019.

- Hellman, Lisa, Navigating the foreign quarters – Everyday life of the Swedish East India Company employees in Canton and Macao 1730-1830, Stockholm 2015.

- Hodacs, Hanna, Silk and Tea in the North: Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth-Century Europe, London 2016.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974 (pp. 81-116 & 251-257).

- ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive, Riksarkivet, Stockholm: The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue. 1752 Götha Leijon (digitised by Warwick Digital Collections).

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Rönnbeck, Klas & Müller, Leos, ‘Swedish East India trade in a value-added analysis, c. 1730–1800’, Scandinavian Economic History Review, Online 2020.

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990 (pp. 178-186 & 257-258).

- Söderpalm, Kristina, ed., Ostindiska Compagniet – Affärer och Föremål, Göteborg 2003.

- Söderpalm, Kristina, ‘Skeppsjournaler från SOIC:s seglation’, Sverige och svenskarna i den ostindiska handeln – I, pp. 31-96, Göteborg 2016.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. DigitaltMuseum (Fabric samples, Anders Berch Collection).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE