ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

THE CLOTHING AND FABRIC TRADE

– in London from 1780 to 1914

This case study will give a few examples of the very extensive continuous textile trade, which had existed for several centuries in London at this time. Including haberdashers, drapers, tailors, dressmakers – named mantua-makers in the 18th century – and many more specialist occupations. The historical essay will be accompanied by trade cards, censuses, artworks, information from a travel journal and comparisons with my earlier research into the drapery trade in the coastal town of Whitby. Emotional perspectives will also be touched upon via the rare depiction of a young draper’s apprentice leaving his mother to settle into his long training period, together with the reality of bankruptcy for many businesses in the rapidly growing trade and desire for shopping.

The artist is unknown for this oil on canvas from ca 1780, but the origin of the motif is likely to have been one of London’s innumerable tailoring establishments, where not only the craftsmen’s everyday working environment is shown, but what can also be seen are such details as remnants of bits of broadcloth and other fabric in the workshop. (Courtesy of: Museum of London, 2002-179, Wikimedia Commons).

The artist is unknown for this oil on canvas from ca 1780, but the origin of the motif is likely to have been one of London’s innumerable tailoring establishments, where not only the craftsmen’s everyday working environment is shown, but what can also be seen are such details as remnants of bits of broadcloth and other fabric in the workshop. (Courtesy of: Museum of London, 2002-179, Wikimedia Commons).The numbers of workers and businesses – drapers, tailors, dressmakers, needlewomen and several other occupations connected with the sewing and selling of clothes – responded to a naturally increasing need according to a town’s size. However, with exceptions to some extent, from and after the mid-19th century, when factories produced ready-made clothes, tailors and dressmakers concentrated more strongly on certain places. A significant period in the textile trade occurred in about 1815; even though the Industrial Revolution had already begun during the second half of the 18th century, it was not until some little way into the 19th that industrial production in the textile field reached its full strength. This meant that everything from fabric, knitted goods, laces and embroidery could now increasingly be made by machinery, which appreciably increased the speed of production and also made it ever more possible for the expanding middle classes, in particular, to buy more clothes for less money.

This depiction of a draper’s apprentice dating ca 1800, gives a rare glimpse into how young some of these boys were at the beginning of their apprentice period. Possibly the image shows an exclusive Paris drapery, but the detailed interior is in many regards comparable to similar trades in London. His mother in up-to-date fashion saying farewell, the boy’s chest with all necessary belongings, the draper’s rolled-up legal agreement etc. This so-called ‘indenture’ was an important document for apprentices as evidence of officially approved proficiency in their particular occupation, as well as under which terms they worked during an apprentice period of usually five to seven years. By Augustin Legrand after an original by Martin Usteri. (Courtesy of: Digital Museum/The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, no 234863).

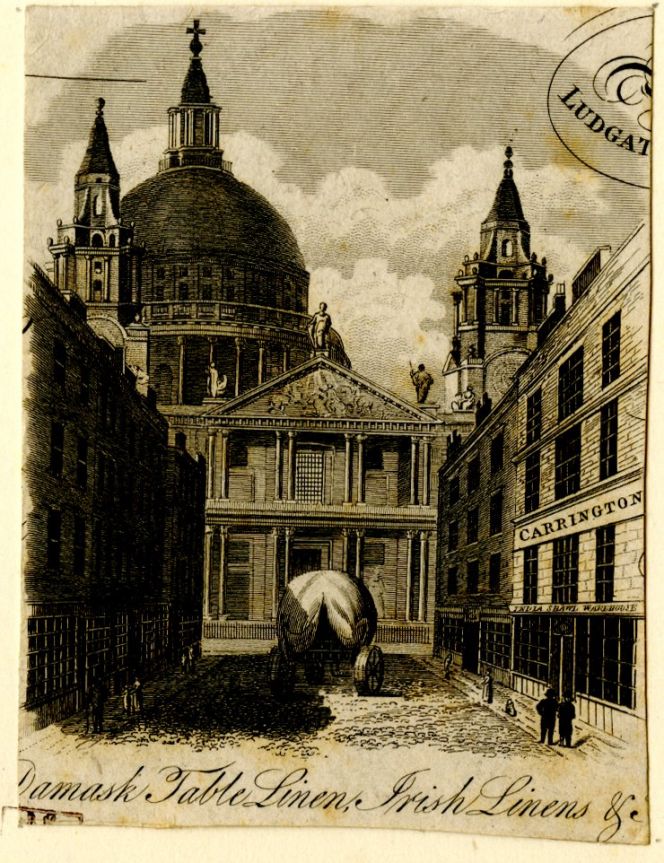

This depiction of a draper’s apprentice dating ca 1800, gives a rare glimpse into how young some of these boys were at the beginning of their apprentice period. Possibly the image shows an exclusive Paris drapery, but the detailed interior is in many regards comparable to similar trades in London. His mother in up-to-date fashion saying farewell, the boy’s chest with all necessary belongings, the draper’s rolled-up legal agreement etc. This so-called ‘indenture’ was an important document for apprentices as evidence of officially approved proficiency in their particular occupation, as well as under which terms they worked during an apprentice period of usually five to seven years. By Augustin Legrand after an original by Martin Usteri. (Courtesy of: Digital Museum/The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, no 234863). In the larger towns and cities either long-established firms expanded or many new specialised shops opened during the 1830s to sell every imaginable clothing detail. Some examples in London were Urling’s Lace Warehouse in Regent Street, J. Holmes’ Shawl Emporium in the same street, the C. & G. Roberts’ warehouse which sold trimmings and lingerie at St Paul’s Churchyard, and Haberdashery Hitchcock and Rogers on Ludgate Hill. This part of an early 19th century trade card, illustrates Ludgate Hill close to St Paul’s Cathedral and some of the textile shops at the time (Courtesy of: British Museum, Collection online, Trade cards, draper, Heal,80.52).

In the larger towns and cities either long-established firms expanded or many new specialised shops opened during the 1830s to sell every imaginable clothing detail. Some examples in London were Urling’s Lace Warehouse in Regent Street, J. Holmes’ Shawl Emporium in the same street, the C. & G. Roberts’ warehouse which sold trimmings and lingerie at St Paul’s Churchyard, and Haberdashery Hitchcock and Rogers on Ludgate Hill. This part of an early 19th century trade card, illustrates Ludgate Hill close to St Paul’s Cathedral and some of the textile shops at the time (Courtesy of: British Museum, Collection online, Trade cards, draper, Heal,80.52).As mentioned above, the shops increased in number and ever more people had an opportunity to find employment in the manufacture and selling of drapery and other textiles. As the supply of available goods continued to grow, many of the larger shops actually developed into department stores. Naturally, the cities went in for the most comprehensive specialisation, both in number, size of businesses and what was on offer for sale, which saw an undiminished increase during the whole period up to 1914. Whilst in a small town, the drapers’ shops often sold everything a customer could want – with the occasional exception of haberdashers and mercers.

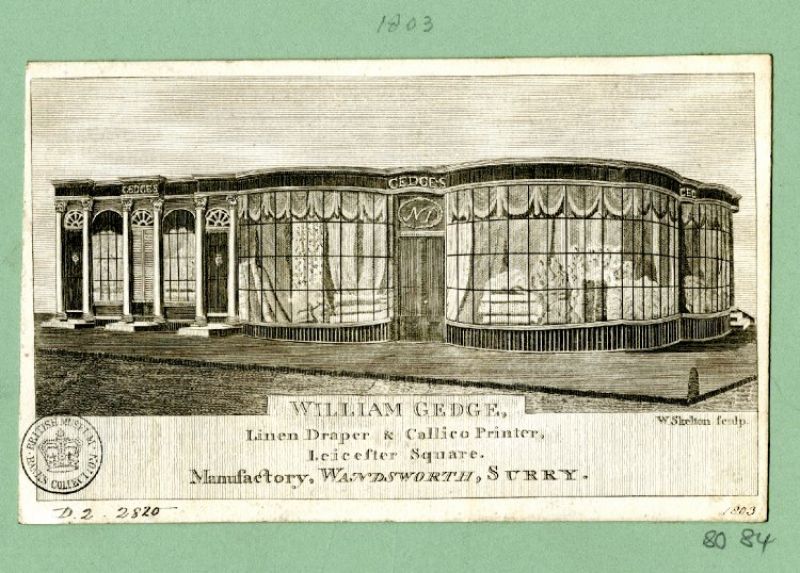

18th and 19th century trade cards are an informative primary source from many perspectives – among hundreds of “textile shops” in the capital William Gedge's Linen Draper & Callico Printer at Leicester Square in London was active around 1800 (dated 1803). His trade card appears to demonstrate the favourable bright conditions of a corner shop with display windows stretching from floor to ceiling, showing off a large selection of printed muslins, linens etc. But by comparing a notice in ‘The London Gazette’ from 1814, one may see the difficulties this and many other businesses – and its employees – faced in the very competitive textile market. It commenced: ‘The Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt bearing date the 30th of October 1809, award and issued forth against William Gedge, of Leicester-Square…’ (British Museum, Collection online, Trade cards, draper, D,2.2820).

18th and 19th century trade cards are an informative primary source from many perspectives – among hundreds of “textile shops” in the capital William Gedge's Linen Draper & Callico Printer at Leicester Square in London was active around 1800 (dated 1803). His trade card appears to demonstrate the favourable bright conditions of a corner shop with display windows stretching from floor to ceiling, showing off a large selection of printed muslins, linens etc. But by comparing a notice in ‘The London Gazette’ from 1814, one may see the difficulties this and many other businesses – and its employees – faced in the very competitive textile market. It commenced: ‘The Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt bearing date the 30th of October 1809, award and issued forth against William Gedge, of Leicester-Square…’ (British Museum, Collection online, Trade cards, draper, D,2.2820).From about the middle of the 19th century, the steadily increasing sales of clothes also necessitated a greater number of shop assistants. This work was considered suitable for young women from the middle classes since it required good manners and standard speech without too strong a dialect. But even if this work was less strenuous than that of home dressmakers and factory workers, here too, pay was low and working hours long. In addition, with the larger stores and department stores in London and other cities, it became normal for shop assistants to live near their work. However, this requirement seems to have become rare by the early 20th century since the 1911 census for the central drapery district of London seldom, if ever, shows tailors, dressmakers or shop assistants living in such places as Montpelier Street, Regent Street, Oxford Street, New Bond Street or Savile Row where many textile-related stores had their premises. There were exceptions, but these were usually tailors or assistants in drapery shops who had reached such a high position that they were able to keep servants in their own homes. There were several examples of this in Savile Row, where the tailor Edward Curties lived with his dressmaker wife Agnes Curties in their household, including both a ‘Cook domestic’ and a ‘Housemaid domestic’. On the same street lived the corset maker Bathilde Louise Gilson, who also had two servants in her household. In other words, while not many textile workers in the early 20th century were able to afford to live near their work in the expensive central parts of London, in a small coastal town like Whitby, it was the exact opposite, with the oldest and most central parts of the town housing large numbers of the town’s poor side-by-side with established drapery stores.

Many large and prominent drapers' establishments were to be found along Regent Street in London, as seen in this 1860s illustration from the 'Illustrated London News', in which the many horse-drawn carriages are actually contributing to a traffic jam caused by shopping (Illustrated London News, 1866).

Many large and prominent drapers' establishments were to be found along Regent Street in London, as seen in this 1860s illustration from the 'Illustrated London News', in which the many horse-drawn carriages are actually contributing to a traffic jam caused by shopping (Illustrated London News, 1866).But the crowded streets of central London caught, for instance already, the attention of the Swedish traveller J P Bager in his Impressions of London from the Late Summer of 1840 (29th August). He noted: ’A considerable obstacle for making headway on the streets is, more than the swarming crowds of people, through which one quickly learns to negotiate on the excellent and wide pavements, the seductively inviting and constantly beautiful and tastefully varied boutiques… In these windows, one can see either a lady or a proud man, made of wax, dressed in the most fashionable clothes, hats, millinery and other adornments so several people can inspect from all sides as they slowly wander around. The owners of houses with such exhibitions are mostly perfumery or fashion traders.’

Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. First and foremost, based on the research linked to ‘Textile Occupations and Trades from a Wider Perspective’ pp. 54-55 & apprentice indenture p. 94, published in the monograph by Viveka Hansen, 2015. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see this book.

Sources:

- Adburgham, Alison, Shops and Shopping 1800-1914, London 1967.

- Bager, J P, Impressions of London from the Late Summer of 1840, London & Whitby 2001.

- British Museum, Collection Online (Search words: 'trade cards draper').

- Census 1911, Findmypast.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Forgotten Victorian Textile Observations’, TEXTILIS (November 7, 2013).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015.

- The London Gazette, Part 1, Jan. 1, 1814 - June 28, 1814, p 891. (The State University of Iowa Library).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE