ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE EMBROIDERERS

– Medieval Textiles

A final essay on the late Medieval textiles in St Petri church will give a brief history of the professional embroiderers’ skills, using designs and how this trade in some areas developed into surprisingly large-scale production centres on the Continent, England and in the Nordic area. These complex and artistic embroideries on silk, velvet or linen fabrics were stitched in workshops by both men and women – the most well-known in Sweden were Albertus Pictor in Stockholm and the nunnery in Vadstena. However, the majority of the preserved examples in St Petri church are believed to have their origin in Flanders.

This close-up detail of a fragmented cross depicting the abbess Brigida from Ireland – originally decorating a chasuble – is one representative example of designs from the highly skilled professional embroiderers in Flanders workshops. The work originate from c.1500. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This close-up detail of a fragmented cross depicting the abbess Brigida from Ireland – originally decorating a chasuble – is one representative example of designs from the highly skilled professional embroiderers in Flanders workshops. The work originate from c.1500. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The coastal town of Malmö probably had no professional embroiderers of its own during the Medieval period, the first known master of this trade was registered in the late 16th century. The reason for this was possibly a long-lasting tradition of importing such goods in the Danish area – which Malmö belonged to at this time – from the Continent. The typical designs from Flanders were researched already in the 1920s by the historian Agnes Branting, who, among various embroidery styles, named one group of these as “The Baldachin School”, when a saint or apostle was traditionally positioned within a baldachin. She was furthermore emphasising that this particular type of complex laid work embroideries have been preserved in a number of Medieval church collections in Sweden, and the standardisation of the designs gives evidence for mass production on an almost “industrial scale”.

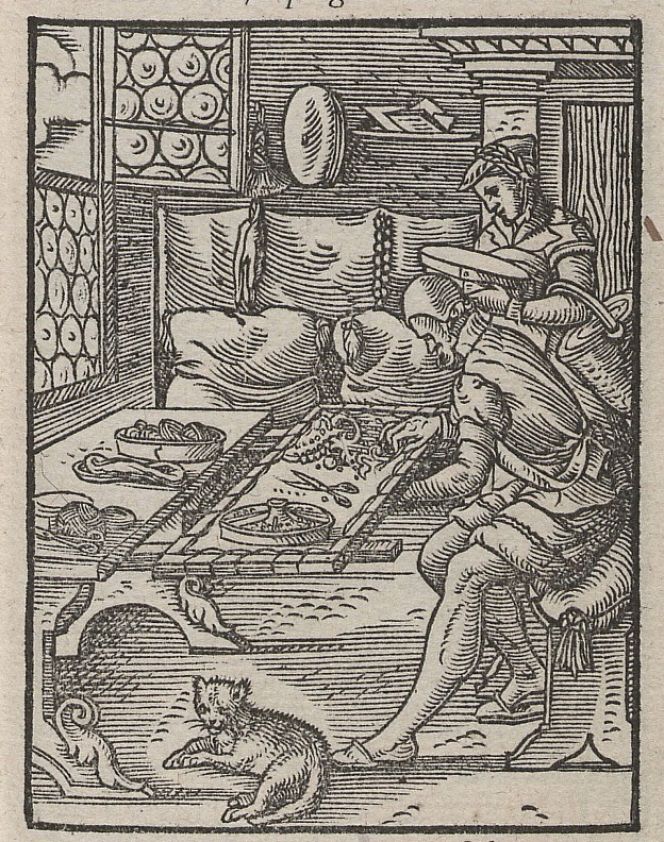

The somewhat later depiction (1568) of “Embroiderer in Silk and Pearls” by Jost Amman gives a detailed impression of how the daily life was carried out in a small workshop. The embroiderer was seated on a bench-cushion for comfort whilst the upper part of the window was open to get in as much light as possible to aid the fine work. He used a frame, various silks and yarns, a round box divided into smaller sections for needles, thimbles, pearls and other necessary items. Most probably, the trade and its methods of stitching etc were very similar during the late Medieval period.

The somewhat later depiction (1568) of “Embroiderer in Silk and Pearls” by Jost Amman gives a detailed impression of how the daily life was carried out in a small workshop. The embroiderer was seated on a bench-cushion for comfort whilst the upper part of the window was open to get in as much light as possible to aid the fine work. He used a frame, various silks and yarns, a round box divided into smaller sections for needles, thimbles, pearls and other necessary items. Most probably, the trade and its methods of stitching etc were very similar during the late Medieval period.From a study of Medieval woodcuts, it can also be understood that a pattern was first marked out on the linen, so the lines of the stitching became visible for the embroiderer. During the work itself, the fabric was stretched in a frame as in the above image; this frame could either be placed horizontally or vertically. Complex laid work and other techniques like long-and-short satin stitches, stem-, chain-, ordinary satin stitch, appliqué, etc, were preferred. A combination of such embroideries resulted in a covered surface, which the late textile historian Agnes Geijer described as “needle painting” or acu pingere in Latin. It may also be stated that preserved accounts from workshops in Florence, listed orders to artists who were paid to make impressions/patterns in watercolour for the embroiderers. Their work was to render the original paintings into embroidery using silk, metallic threads, and pearls. The many workshops in Flanders probably worked in a similar manner.

This fragmented and worn piece of a late Medieval embroidery in laid work, gives a detailed view of the embroiderer’s work; we can get a close-up of the careful design and position of each and every stitch, the use of silks and metallic threads together with glimpses of the typical plain-woven unbleached foundation. The fragment is today stitched on an additional linen for a stabilisation of its frail state. Height 17 cm and width 19,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This fragmented and worn piece of a late Medieval embroidery in laid work, gives a detailed view of the embroiderer’s work; we can get a close-up of the careful design and position of each and every stitch, the use of silks and metallic threads together with glimpses of the typical plain-woven unbleached foundation. The fragment is today stitched on an additional linen for a stabilisation of its frail state. Height 17 cm and width 19,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.To include the appliqué technique – with pieces of silk fabric – in these ecclesiastical embroideries was quite common, as described in an earlier essay. These additions were essential parts of the designs; for example, the professional embroiderer gave the depicted figures facial expressions with suitable coloured silks. These patches were commonly stitched onto the embroidery with tiny back stitching. One problem that could have arisen during the stitching was often the small silk patches' tendency to become frayed in the edges. To prevent this inconvenience, the embroiderer used beeswax as a natural fixative. Furthermore, the embroideries were often adorned with various fringes or ribbons for decorative purposes and to hide unwanted seams. Whether this additional work was added in the professional embroiderers’ workshops or if these finalising fringes, etc., were woven/plaited at a later stage when the vestments were made is uncertain. The two images below give two examples of decorative fringes, which once belonged to liturgical vestments or altar decorations during the late Medieval period in St Petri church.

A tablet-woven silk ribbon with fringe in red, white, yellow and green/today faded to blue and metallic thread/gold. The work is dated to the late Medieval period. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

A tablet-woven silk ribbon with fringe in red, white, yellow and green/today faded to blue and metallic thread/gold. The work is dated to the late Medieval period. Photo: The IK Foundation, London. Red silk fringe, once part of an altar textile or liturgical vestment, late Medieval period. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Red silk fringe, once part of an altar textile or liturgical vestment, late Medieval period. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of St Petri church textiles, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Kyrkliga textilier i Malmö – från medeltid till barock’, Elbogen pp. 61-135. 2000.

- Sachs, Hans & Amman, Jost, Eygentliche Beschreibung – Aller Stände auff Erden / Hoher und Niedriger / Geistlicher…, Frankfurt am Mayn 1568 (Facsimile Aarhus 2012, p. 81).

- St Petri Church, Medieval Church Collection, Malmö, Sweden (researched in 1999 & 2000 for the above article).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE