ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE FEMALE WEAVERS

Documentation of 18th & 19th century double interlocked tapestries

Female weavers who produced double interlocked tapestries or “rölakan” as a professional occupation were extremely rare during the 18th and 19th centuries, which also was confirmed during the documentation between 1984-1991 including more than 1.600 examples of these tapestries. Only one woman could be placed in this category with certainty, while other weavers – who built up dowries for their daughters or wove to decorate their homes for festivities – have been found during both my observations and by earlier collectors, researchers and documentations. However, the artists/weavers of the largest part of these beautiful textiles are anonymous today. The illustrations and texts below briefly describe the knowledge, traditions and circumstances surrounding the female weavers of Skåne in southernmost Sweden.

This is a unique double interlocked tapestry woven by the professional weaver Bengta Oredsdotter in Lyngby 1828, dedicated to the crown prince Joseph Frans Oscar (1799-1859). It is unknown if Sweden’s king-to-be received this decorative textile. Private owner. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

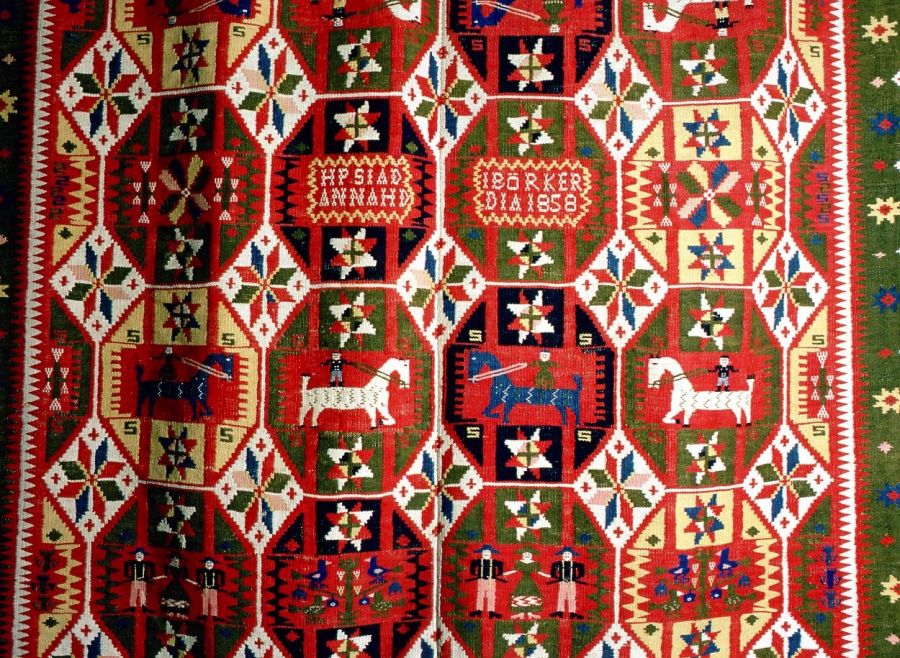

This is a unique double interlocked tapestry woven by the professional weaver Bengta Oredsdotter in Lyngby 1828, dedicated to the crown prince Joseph Frans Oscar (1799-1859). It is unknown if Sweden’s king-to-be received this decorative textile. Private owner. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).The main part of Bengta Oredsdotter’s production is believed to have consisted of large bedcovers designed with octagons in rows, but the Gärds/Villands districts' typical stylistic small trees placed in these octagons were by her replaced – as well as by some other weavers in the area – with a myriad of various birds, people, deers, flowers etc. Uncertainties are, on the other hand, not unusual when trying to trace a particular piece of textile’s history. This can be exemplified with the bedcover below, dated 1858, which originates from the last decade when the individual “Bengta style design” has been identified, but the catalogue description from Kulturen in Lund notes instead that the textile was woven by Anna Håkansdotter born in 1839 “Anna HD” in marking. This statement must, by experience, be given some reservations, foremost because of the complexity of the patterns, the fineness in quality and the perfect finish of the bedcover when woven by a woman only 19 years old. Probably her more trained mother Ingar Andersdotter marked “IAD” on the bedcover, was the weaver of this exquisite design.

Even if many double interlocked tapestries were marked with both year and initials, it is even so quite rare to know the name of the weaver. The same apply to this worn cushion, in spite of the year “1817” and the woven initials “HD” placed on the opposite side. Part of travel cushion from the districts Gärds or Villands, Skåne. Private owner. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Even if many double interlocked tapestries were marked with both year and initials, it is even so quite rare to know the name of the weaver. The same apply to this worn cushion, in spite of the year “1817” and the woven initials “HD” placed on the opposite side. Part of travel cushion from the districts Gärds or Villands, Skåne. Private owner. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London). Part of bedcover dated 1858 in double interlocked tapestry, Västra Vram parish, Gärds district, Skåne. Owner: Kulturen in Lund, Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Part of bedcover dated 1858 in double interlocked tapestry, Västra Vram parish, Gärds district, Skåne. Owner: Kulturen in Lund, Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London). The history of this travel cushion was explained to me in person by the former keeper Gustaf Åberg of Österlen museum in the late 1980s. The cushion had been inherited through his family from his grandmother’s grandmother dating back to the late 18th century. After the aural history of his family, the double interlocked tapestry textile was woven by Toren Andersdotter who was lame and therefore already as a child restricted to the indoors. The weaving became a natural occupation for her from early years, which later on made her a skilled weaver. Luggude district, Skåne, Sweden. Owner: Stiftelsen Jöns Jons gården, Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

The history of this travel cushion was explained to me in person by the former keeper Gustaf Åberg of Österlen museum in the late 1980s. The cushion had been inherited through his family from his grandmother’s grandmother dating back to the late 18th century. After the aural history of his family, the double interlocked tapestry textile was woven by Toren Andersdotter who was lame and therefore already as a child restricted to the indoors. The weaving became a natural occupation for her from early years, which later on made her a skilled weaver. Luggude district, Skåne, Sweden. Owner: Stiftelsen Jöns Jons gården, Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).The early research of old textiles from the area of “Malmöhus län” by the local handicraft organisation shows us many details of female weavers and their families. At the time of their research during the early 20th century, there was still substantial local knowledge about the people connected to the textiles as well as the ownership over a more extended period. For example, the depicted bedcover below in the double interlocked tapestry is explained in translation (see image below): ‘The bedcover is marked TLS – BTD. It is said to have been woven by Anna Nilsdotter in Skegrie, Tommarp parish, Skytts district, in 1818, shortly before she was married. It had first been inherited by the daughter Anna Hansdotter and then by the daughter’s daughter Hilda Hansson in Fuglie parish, Skytts district. The latter, who is unmarried, has recently left it to a relative, and the bedcover is nowadays owned by Ellen Sonesson in Söderhamn, Hälsingland’.

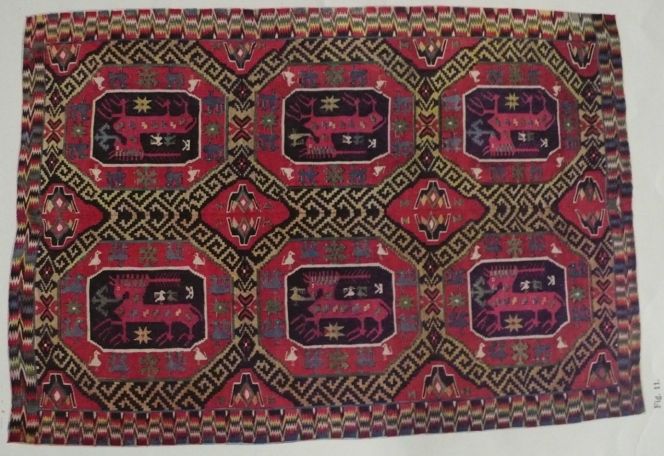

Bedcover dated 1818 in double interlocked tapestry, Skegrie, Tommarp parish, Skytts district, Skåne. (From Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhus län, 1916, Fig. 11).

Bedcover dated 1818 in double interlocked tapestry, Skegrie, Tommarp parish, Skytts district, Skåne. (From Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhus län, 1916, Fig. 11).Even if many Swedish museums started their collection work of older textiles just as early as above mentioned handicraft organisation – some of them already during the late 19th century – the aims or circumstances appear not to have been precisely the same. The textiles in museum collections can often be traced to an exact district and not seldom also the precise parish, but it seems to have been quite unusual to note any facts about the weavers' names or families. Presumably, these facts were not present or known at the time of the collection/donation/purchase of the items. On the other hand, some museums included detailed descriptions of the buyers/donors/collectors of the textiles and the dates on which they were made.

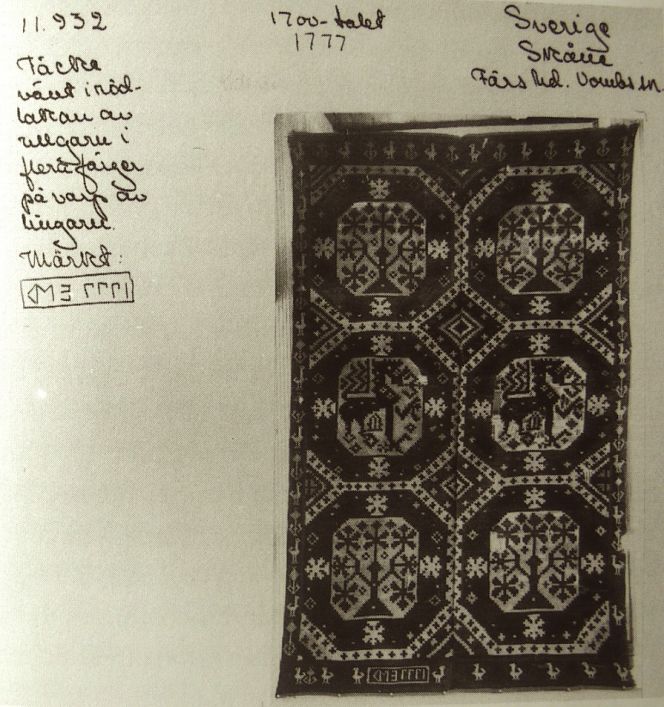

Here exemplified with a catalogue card of a bedcover owned by Malmö museums. Information about the female weaver is not present, but it is evident that the double interlocked tapestry was woven in Färs district, Vombs parish ‘of wool in several colours on warp of linen yarn, marked 1777 EMD’. Owner: Malmö museums, part of text in translated quote. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Here exemplified with a catalogue card of a bedcover owned by Malmö museums. Information about the female weaver is not present, but it is evident that the double interlocked tapestry was woven in Färs district, Vombs parish ‘of wool in several colours on warp of linen yarn, marked 1777 EMD’. Owner: Malmö museums, part of text in translated quote. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).Some individuals linked to various early museums in Sweden were of greatest importance for the understanding of collecting/documenting home-crafted textiles, some of them can here be mentioned briefly: Arthur Hazelius, the founder of the Nordic Museum and Skansen in Stockholm, G: J:on Karlin, founder of Kulturen in Lund, Vivi Sylwan at Röhsska museum in Göteborg and Emelie von Waltertorff engaged at both Kulturen and the Nordic museum with documentation of textiles. However, when it came to the early documentation of double interlocked tapestries – together with many other decorative techniques – Lilli Zickerman was the most important researcher. Her lifelong commitment to the Swedish handicraft traditions started already in the 1890s and lasted up to 1937 with the publication Sveriges folkliga textilkonst – Rölakan (Swedish Folk Textile Art – Double interlocked tapestries), but she is probably best known for her documentation work between 1910-1931 which resulted in 24 000 plates and photographs, today kept at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm.

![At the time for my documentation, copies from the county of Kristianstad was placed at the local handicraft organisation where I had the opportunity to study 317 plates depicting double interlocked tapestries from said county. Here exemplified with a partly coloured photograph of a cushion from Ingelstads district in south eastern Skåne. Owner [1991] The Handicraft Organisation in Kristianstad, pl. 378. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-7r-664x865.jpg) At the time for my documentation, copies from the county of Kristianstad was placed at the local handicraft organisation where I had the opportunity to study 317 plates depicting double interlocked tapestries from said county. Here exemplified with a partly coloured photograph of a cushion from Ingelstads district in south eastern Skåne. Owner [1991] The Handicraft Organisation in Kristianstad, pl. 378. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

At the time for my documentation, copies from the county of Kristianstad was placed at the local handicraft organisation where I had the opportunity to study 317 plates depicting double interlocked tapestries from said county. Here exemplified with a partly coloured photograph of a cushion from Ingelstads district in south eastern Skåne. Owner [1991] The Handicraft Organisation in Kristianstad, pl. 378. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets Konst och Kulturhistoria, Christinehof 1992 (pp. 139-47 & 173-87).

- Malmöhusläns hemslöjd, Gammal allmogeslöjd från Malmöhus län, Malmö 1916.

- Zickerman, Lilli, Sveriges folkliga textilkonst – Rölakan, Stockholm 1937.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE