ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE NORDIC IRON AGE

– Clothing and Dyes

The approximate first thousand years of the Nordic Iron Age (500BC-600AD) was a period when textile-related finds first decreased and then increased in the Malmö area, compared to the previous Bronze Age. The many archaeological excavations in the past two decades have also been able to unearth a variety of tools, fragments, seeds, etc, making it possible to add new facts and draw conclusions about the development of this period. This second essay on the textile history of the said area in southernmost Sweden will discuss the introduction of dyeing from the knowledge learned via local excavations and comparisons with some remarkably well-preserved Danish bog finds.

Textile fragments in twill have been found at excavations in the Malmö area, a weaving technique which gives more variation compared to the plain weave which was known here as early as the Nordic Bronze Age. The depicted fabric is a historical reproduction of such a woollen twill quality; which in technique, material, density and design has aimed to be as authentic as possible compared to qualities from the Iron Age. The fabric was hand-woven in 1986 by Peter Anderson, using the wool of the Herdwick sheep. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Textile fragments in twill have been found at excavations in the Malmö area, a weaving technique which gives more variation compared to the plain weave which was known here as early as the Nordic Bronze Age. The depicted fabric is a historical reproduction of such a woollen twill quality; which in technique, material, density and design has aimed to be as authentic as possible compared to qualities from the Iron Age. The fabric was hand-woven in 1986 by Peter Anderson, using the wool of the Herdwick sheep. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The oldest period of the Iron Age in the Malmö area gives few, if any, clues of textile traditions or the population’s clothing and everyday life – which is also the case for many other researched Nordic settlements of this time. Reasons for the decrease in finds are somewhat uncertain, but a substantially colder climate and more rain are believed to be significant factors. In other words, the heavy clayey soils of this region made the former farmers’ grounds impossible to cultivate, so for hundreds of years, they had to settle elsewhere in higher and drier places. However, a general description of textile-related finds from some other Nordic settlements can shortly be summarised as primarily locally produced fabrics in twill or plain weave made of wool from black, brown or greyish sheep and an introduction of dyes. At the same time, all sorts of skins were still crucial for larger garments such as skirts or capes and other clothing suitable for the cold climate.

The period 100-600AD is much richer in findings, including some new developments for textile production in the area. Awls made of iron were one such tool – a stronger material than the earlier ones of bronze and bone – used in preparing holes for the stitching of skin garments. One of these awls has been located as a burial find from the Höjahögen in Malmö and a similar tool in a grave at Limhamn. At the latter-mentioned excavation, a half-moon-shaped knife was also unearthed, which is believed to have been used for the skin/leather/fur craft. Furthermore, various research from the Nordic area has come to the conclusion that larger garments of skin, to some extent, diminished during this period and instead came into fashion as a luxury material for accessories like collars, hats or mittens. The upright loom had now simultaneously developed to become the primary tool for producing garments and other necessary furnishing textiles for the home. This circumstance can be proved through several finds; for example, from excavations at Fosie, the archaeologists registered a large number of loom weights, spindle whorls, bone needles and a scissor of iron. Other finds include textile fragments, particularly from Kristineberg, where nine tiny pieces of woollen fabric (1,5cm x 1,5cm or smaller) were unearthed in two graves. The fabrics could be categorised into two types of twill – circa 10-12 warp threads/cm, respectively, 15 threads/cm. A similar find was located in a female grave from Hindby, where twill-woven woollen fragments have been preserved because of the close proximity to dress fibulas of bronze.

Several plants were known for the dyeing of yellow during this period, but dyer’s weed (Reseda Luteola) is believed to have been the most common plant, due to chemical analysis on excavated textile finds in both Scandinavia and Great Britain. While clubmoss (instead of alum in later periods) is thought to have been the main mordant for textile dyeing of yarn and cloth. For dyeing of blue – woad (Isatis tinctoria) – was at least already in use around 2000 years ago in the Nordic area. Depiction of plain weave in two colours (Illustration: Helen Hodgson, 2001).

Several plants were known for the dyeing of yellow during this period, but dyer’s weed (Reseda Luteola) is believed to have been the most common plant, due to chemical analysis on excavated textile finds in both Scandinavia and Great Britain. While clubmoss (instead of alum in later periods) is thought to have been the main mordant for textile dyeing of yarn and cloth. For dyeing of blue – woad (Isatis tinctoria) – was at least already in use around 2000 years ago in the Nordic area. Depiction of plain weave in two colours (Illustration: Helen Hodgson, 2001).There is only clear proof that wool was spun for the population’s need for clothing and other textiles; no flax fibres or fragments have been found in the area from this part of the Iron Age. Nevertheless, large amounts of flax seeds were unearthed at several excavated settlements, so maybe flax was by now not only used for cooking but also for the weaving of linen fabric. From a larger Nordic perspective, local production of linen cloth was introduced in about 200AD and first became common approximately 400 years later. At the same time, the more widespread research in the Nordic area also indicates that sheep started to be bred around 100AD to obtain better qualities as well as more varied types of wool for textile production. White and light grey wool seems to have been desired, probably not for the wish of white clothing, but instead, white or light grey wool was ideal for the developing fashion of dyeing woollen yarn or cloth into various colours.

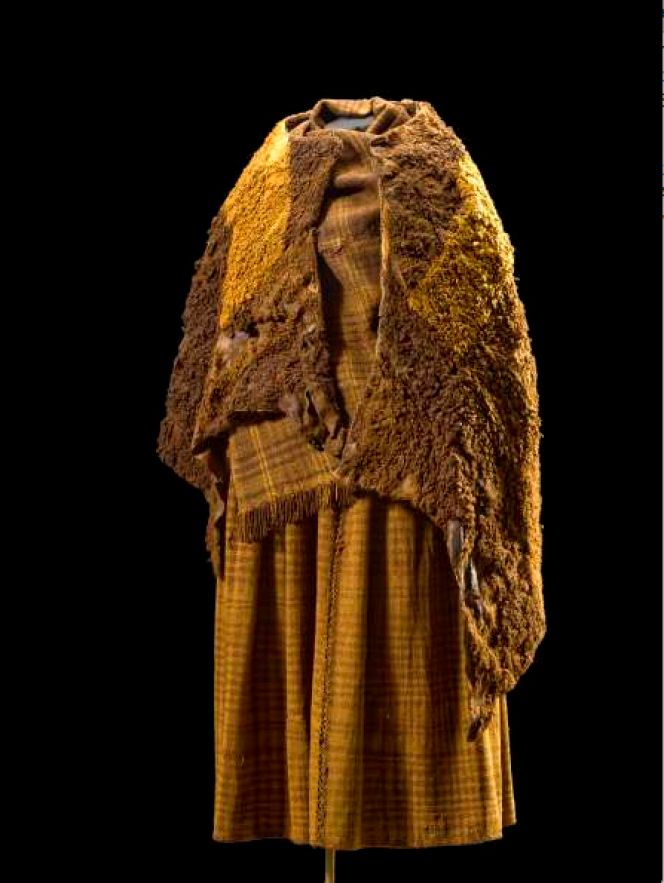

This very well-preserved Danish Iron Age bog find from “Huldremose”, originating from the 2nd century BC can give good insight and be a comparison into a woman’s clothing from a wider geographical Nordic area. The more than 40 year old female was once buried fully clothed along with all her garments – consisting of a checked woollen skirt and scarf together with two skin capes – have been studied in great detail by the National Museum. Her clothing of wool was also dyed, explained by the museum in the following way: ‘The long period in the water of the bog has turned the clothes brown. Colour analysis has shown that originally the skirt was blue and the scarf was a red colour’. (Courtesy of Nationalmuseet in København, Denmark.)

This very well-preserved Danish Iron Age bog find from “Huldremose”, originating from the 2nd century BC can give good insight and be a comparison into a woman’s clothing from a wider geographical Nordic area. The more than 40 year old female was once buried fully clothed along with all her garments – consisting of a checked woollen skirt and scarf together with two skin capes – have been studied in great detail by the National Museum. Her clothing of wool was also dyed, explained by the museum in the following way: ‘The long period in the water of the bog has turned the clothes brown. Colour analysis has shown that originally the skirt was blue and the scarf was a red colour’. (Courtesy of Nationalmuseet in København, Denmark.) Northern bedstraw (Galium boreale) is a useful plant for both sustainable yellow and red dyes on wool. Carbonised seeds of several Galium species have also been found in excavations in Lockarp, Svågertorp and other places close to settlements in the Malmö area, together with other seeds believed to have acted as cultivating plants. That some species of this genus was used for textile dyeing is one likely possibility. Northern bedstraw in late June. (Photo: Viveka Hansen.)

Northern bedstraw (Galium boreale) is a useful plant for both sustainable yellow and red dyes on wool. Carbonised seeds of several Galium species have also been found in excavations in Lockarp, Svågertorp and other places close to settlements in the Malmö area, together with other seeds believed to have acted as cultivating plants. That some species of this genus was used for textile dyeing is one likely possibility. Northern bedstraw in late June. (Photo: Viveka Hansen.)Not all textile production was local; it was widespread, and far-reaching trade was well-developed during the Nordic Iron Age. A piece of clear evidence for this early commerce was found during an excavation at Västergård in connection to the building of the Öresund bridge, described as followed by the Malmö Museum: ‘According to the conservators, the object consists of a metal core which is entwined with a type of textile fibre, the find was located close to the cranial remains.’ (No: MHM9149, in a translation from Swedish). The metal core of the thread suggests that the person at the time of his/her burial was dressed in exclusively imported fabrics, while there is no proof that spinning thread either with metal as a core or entwined around a textile material was known in the Nordic area at this time.

Notice: Place names in italics are geographical areas, today within or very closely situated to the city of Malmö. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of excavated fragments, tools, etc, please see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen, 2001.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Förhistoriska och Medeltida Textilier i Malmö’, Elbogen 2001, pp. 73-144 (pp. 89-99).

- Nationalmuseet, København, Denmark (Digital source, The Woman from Huldremose).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE