ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

THE STORY No. 1 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Preparations prior to a long-distance Journey in the 18th Century

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

As for more extended expeditions and research-aimed journeys today, preparations were wide-ranging during the 18th century – from practical, theoretical, mental and intellectual perspectives alike. Initially, depending on the traveller’s destination, the climate in the intended visited areas, and, if known, the length of time away, a multitude of hands-on skills also had to be taken into account. Such as making linen shirts stitched by a female relative or seamstress, ordering new clothes at a tailor or sorting out one’s old suitable garments. Other undertakings of importance were to prepare suitable team members, strengthen beneficial friendships, improve language skills, general fundraising and finance, buy required books, paper, pencils, bags, maps (if any existed), instruments, medicines, receive one’s instructions, to assess risks, plan for various modes of transport etc. so the journey was conceivable to fulfil in the most advantageous way from both scientific and health and safety points of view.

To be able to move substantial quantities of personal belongings and collections during natural history journeys, the ship was superior to all other means of transport. Limitations for the size of storage space on an East India Company ship and other sailing routes alike were mainly dependent on one’s position onboard. On the home journey, it was customary to maximise the luggage, amassed specimens etc. after each and everyone’s wishes, but the risk of hazardous weather was the same for the captain as the travelling naturalist – often working as ship’s chaplain or doctor. As the ship itself was such an essential part of long-distance travel, some individuals made detailed depictions in their journals. Here exemplified with calm waters at Wampoo in China, included in the 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s East India journal (1746-1749). (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm… M 292).

To be able to move substantial quantities of personal belongings and collections during natural history journeys, the ship was superior to all other means of transport. Limitations for the size of storage space on an East India Company ship and other sailing routes alike were mainly dependent on one’s position onboard. On the home journey, it was customary to maximise the luggage, amassed specimens etc. after each and everyone’s wishes, but the risk of hazardous weather was the same for the captain as the travelling naturalist – often working as ship’s chaplain or doctor. As the ship itself was such an essential part of long-distance travel, some individuals made detailed depictions in their journals. Here exemplified with calm waters at Wampoo in China, included in the 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s East India journal (1746-1749). (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm… M 292). The majority of the travelling field naturalists in the Linnaean network were not from well-to-do families and had limited financial resources, so an essential part of the preparation was to find funds for the journey or at least cover part of it before setting out. This could often be a lengthy process, but several options were available. Natural history journeys like these were financed via the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Royal Society or similar European academies, by a parliament, via bursaries or by wealthy patrons interested in botanical specimens or natural history in general. Working as a tutor before or during the journey, borrowing money for daily expenses, having a paid situation as a ship’s chaplain or surgeon on an East India Company ship, combining one’s natural history aims with military employment, being a diplomat or politician, or on rare occasions having a professorial chair on the outset of the voyage were also ways to finance the expeditions.

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) himself, as a young student in the early 1730s, made repeated requests for money from the Royal Society of Sciences in Sweden (Kongl. Wettenskaps Societeten) before his planned Lapland journey. On 15 December 1731, he asked for financial aid, motivated in various ways via work he hoped to fulfil. Further, he listed qualities of a successful traveller – according to his own notes, he possessed most of these requirements:

- 'To be Swedish-born.

- To be young and able to climb the steepest mountains.

- To have good health.

- Energetic and determent.

- Unbound of a position: free to travel.

- Unmarried.

- Natural historian and Medicus.

- To understand the three Kingdoms of Nature.

- Be able to draw.’

Despite his efforts, he did not get any reply to the request, so he reapplied on 14 April 1732 to the same Society, and this time, 12 days later, he received 400 Daler in copper coins [Rixdollar copper coin] for the journey.

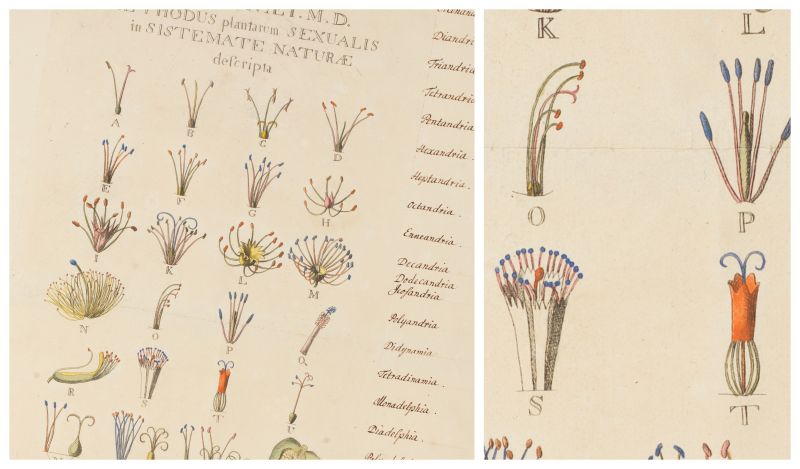

The above colour plate of Linnaeus’ sexual system was presented by Ehret in 1736 and initially included in Genera Plantarum, printed in Leiden during the following year. One of the most significant knowledge to prepare for, not only during their student years but equally to repeat prior to long-distance voyages must have been the taxonomic botany. To be able to identify species within a genus accurately. To have the appropriate skills in describing each and every plant in Linnaeus’ correct reformed terminology – to avoid misunderstandings – was seen as of even greater importance when previously “undiscovered” species were located in far-flung countries.

However, finding funds for a natural history journey often has been lined with obstacles. One such event was the actual preparations for a North American journey, which can be traced in unusual detail via correspondence from 1745 to 1747 – including Linnaeus, the future traveller Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), his patron, friend and employer Sten Carl Bielke (1709-1753) and other involved individuals. In several letters from Kalm to Bielke, it is possible to follow the young man’s hopes, disappointments and up to the final satisfaction when financial matters were solved. On 8 November 1745: ‘So far Professor Linnaeus has not received any news from the Royal Academy of Sciences regarding my American journey…’, and Kalm doubted their interest in giving financial support. About half a year later, or about 16 months before his actual journey to America started, he seems to have had some expectations and simultaneously considered additional options: ‘Otherwise I have asked Professor Linnaeus to sincerely inform the keeper of Chamber Mr Hårleman, that I, as a proof for my genuine desire to travel, I am satisfied with that part the Board of factory industries [Manufactur-contoiret] provides for the journey; if I manage to get an additional scholarship it is even better…’(3 June 1746). However, about one month later, Kalm seems to have become impatient as he was ready to travel but lacked the necessary funds and thought that he had wasted his time waiting: ‘So far I have heard nothing about the American journey, and will soon believe that the Public [institutions] have no interest or opinion on the matter…’ (2 July 1746). Similar thoughts were repeated in several letters until 3 April 1747 when another opportunity to finance the journey arose: ‘I have written to Dr Browallius, and mentioned if he can present a professorial chair for me in Åbo, I will use the salary of the same for the American journey, but only if it may be arranged during this year, as I grow tired of waiting for this journey…’. His professorship in Åbo [Turku] became a reality in August 1747, and already two months later, his period of travelling to North America started from Lövsta close to Uppsala in Sweden.

Kalm travelled over land and about a week later arrived at the coastal city of Göteborg, where he received Letters of recommendation – an important preparation process before the journey to be accepted in a satisfactory manner by men of influence. Another significant detail during extended travels in the 18th century was to give information about to whom his letters should be redirected and when this adjustment to circumstances started. On 13 October 1747, he wrote to Bielke: ‘P.S. Now Mr Baron may not send me any more letters to this place, the ones you send to England I ask you to write in very clear handwriting…Mr Director Grill is endlessly kind to promote my journey and hand me Letters of recommendation for native Englishmen in London, which will give me education and show me all that concerns their household economy.’ To be patient was further emphasised, as they had to wait six weeks in Göteborg before the ship sailed. He wrote on 18 November: ‘…we waited 3 weeks for the skipper before he was organised, and now we have waited about 3 weeks for wind…’ Kalm also referred to his assistant in this writing, already before the ship had left Göteborg harbour: ‘I am so pleased with Lars [Jungström], that I do not want to change for however they liked to assist me; and I do not need to mention something from Nature more than once, for instance, a herb, a rock etc. before he remembers it.’ This important planning in the initial stage resulted in Kalm having Lars Jungström as a valuable and knowledgeable assistant during the entire voyage stretching from Norway, England to the North American colonies – until they returned to Sweden in the summer of 1751.

Two other aspects linked to the planning of natural history journeys may be gleaned from the correspondence between Linnaeus and the physician and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Abraham Bäck (1713-1795) in 1746. Both men and other individuals in their network were in a hurry to decide whom to send as a physician on the next East India Company ship setting sail within a fortnight – that is, which young naturalist was most suitable and available for such a task. Linnaeus, former student and assistant on his Västergötland Journey in Sweden the very same year, Erik Gustaf Lidbeck (1724-1803), was referred to. Still, according to Bäck, on 9 October, there were obstacles: ‘…that M[r] Lidbeck, as I today presented to M[r] Grill, is not able to say if he gets permission from his parents to travel, and that he has difficulties to be ready so soon, he would rather wish to prepare for the coming year.’ Even if Lidbeck was 22 years old, he still had to take advice from his parents; this was probably a stage to consider prior to a journey that several other young men also had to take into account. Furthermore, Lidbeck never travelled to East India; he became the director of a plantation work, Plantageverket, in Lund, southernmost Sweden, where he lived until old age in 1803. Linnaeus also planned ahead for his own trip to the province of Skåne (1749) in a letter to Lidbeck dated 1 April that same year, as he intended to visit him in Lund: ‘...if only two of us came together, then we were welcomed at the rectory and with the aristocracy. Were we more in number, they would have difficulty with food, beds, chambers, horses etc., whereas we only were two, we were everywhere welcomed.‘

Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770). Oil on canvas by Joseph Aved (1702-1766). (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. NM 5535. Wikimedia Commons).

Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770). Oil on canvas by Joseph Aved (1702-1766). (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. NM 5535. Wikimedia Commons).Even if Carl Linnaeus had had a professional chair in botany for about ten years, he needed to find funds to cover expenses, etc., before his travels to Skåne in 1749. In a letter dated 15 March to Count Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770), portrayed above circa 1740, Linnaeus mentioned his intention to depart as soon as he had received the grant covering his expenses from the Royal “stats contoiret”. Additionally, he kindly asked the wealthy Tessin to inform him about the grant. The financial circumstances became solved, and he set out from Uppsala on 24 April – this journey, as well as his two previous in 1741 and 1746, were financed by the parliament and been regarded as beneficial for the development potential of the country’s mercantile economy.

To address letters of recommendation for his former students prior to various longer and shorter journeys – has been referred to from the 1740s – but this matter was an ongoing process through the years for Linnaeus. One such example in a letter from Claes Alströmer (1736-1794) on 19 December 1759, a month before his voyage was planned to start via a Swedish East India Company (SOIC) ship sailing from Göteborg via Cadix in Spain. It includes information about his travels after that, which he intended to continue through Portugal, Spain, France, England, Holland, and German lands, and then back home to Sweden. Due to this tour, the young naturalist asked Linnaeus to write suitable recommendations that would give him access to otherwise unattainable personal contacts. The former student Anton Rolandsson Martin (1729-1786), in the foreword of his diary in 1758, wrote that he was grateful for all assistance before the journey. This included recommendations to make such travels possible, not only from a financial perspective but also logistically, to find a suitable ship sailing in these northern waters willing to make room for a naturalist.

For a group of individuals to gather before a journey was another way of planning ahead, which Linnaeus’ apostle Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) became part of after his student years in Göttingen and Uppsala. In the autumn of 1760, all six participants were assembled in København to determine their plans for Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia), which they began on 7 January 1761. Sadly, the journey was troubled throughout, and Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) returned to Denmark in September 1767 as the sole survivor. The apostle Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) was contemporary with these travellers. At the outset of his journey in August 1770, he made a few enlightening notes about preparations when still in Uppsala. ‘After having spent nine years at the University of Upsal, the most respectable in Sweden, and passed the usual examinations for taking the Degree of Doctor of Physic, I obtained from the Academical, Consistory the Kohrean Pension for travelling, which, in the space of three years, amounts to 3800 Daler in copper coins, and with my own little stock, enabled me to undertake a journey to Paris, with a view to my farther improvement in Medicine, Surgery, and Natural History.’ Furthermore, Thunberg was fortunate to return home after nine years in 1779 and live on to old age until 1828.

Joseph Banks, here portrayed on oil on canvas by Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), circa 1771-1773, after their three-year global voyage. (Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5868. Public Domain).

Joseph Banks, here portrayed on oil on canvas by Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), circa 1771-1773, after their three-year global voyage. (Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5868. Public Domain).Other ways of planning may be gleaned from the botanists Daniel Solander (1733-1782) and Joseph Banks (1743-1820) on James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage, as they relied on their servants for practical preparations before the ship sets sail in 1768. Even Cook had to remind them via a message on 14 August: ‘Dispatched an express to London for Mr Banks and Dr Solander to join the ship, their Servants and baggage being already on board.’

Judging by surviving correspondence, though, there seems to be some confusion about waiting time in Plymouth as it was mentioned that Joseph Banks and company visited the opera, etc., on the 15th in London. Whilst Banks’ journal in Plymouth on 25 August in 1768 stated: ‘After having waited in this place ten days, the ship, and everything belonging to me, being all that time in perfect readyness…’. Even if organisation and preparation were thorough, waiting times were unavoidable at the time of sail. Shortly after their return from the circumnavigation almost three years later, in July 1771, Solander and Banks began to draw up guidelines for taking part in a second voyage on Cook’s ship, which would have begun as early as 1772 but was never materialised for the two men. Instead, they travelled to Iceland via Scotland in the same year. Banks were also in various ways involved in preparations for other expeditions; one such example was for an old friend from the student years at Eton, Constantine John Phipps (1744-1792), who made ‘A Voyage towards the North Pole undertaken by his Majesty’s Command 1773’. Phipps was the commander on the Racehorse, sailing as far north as the most northern part of the Spitsbergen archipelago to the Seven Islands; in the Introduction of his journal, a circumstantial account reveals some necessary preparations on a long voyage in Arctic waters. ‘Some small but useful alterations were made in the species of provisions usually supplied in the navy, and an additional quantity of spirits was allowed for each ship to be issued at the discretion of the commanders when extraordinary fatigue or severity of weather might make it expedient. A quantity of wine was also allotted for the use of the sick. Additional clothing adapted to that rigour of climate, which from the relations of former navigators we were taught to expect…’. He also dealt with the importance of receiving specialist advice in disciplines where you lacked knowledge in order to fulfil your obligations: ‘To Mr Banks, I was indebted for every full instruction in the branch of natural history, as I have since been for his assistance in drawing up the account of the productions of that country; which I acknowledge with particular satisfaction, as instances of a very long friendship’.

Among the seventeen apostles, Carl Peter Thunberg’s continuous journey abroad was the most extended in time, lasting nine years during the 1770s. His visit to Edo [today Tokyo] demanded incredibly rigorous preparation in the port of Nagasaki for him to be able to deport himself correctly according to the standards of the host country, choosing suitable presents, etc., in which fabrics and clothes played crucial parts. However, preparations for his entire voyage to Japan started already in Holland and Africa with several years of language training, as Thunberg had to present himself as a Dutchman, with no other Europeans being allowed to visit Japan. Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) prepared himself primarily by reading Arabic, which would enhance his possibility to make correct observations of the trades and of everyday life in general. Peter Forsskål, on the other hand, had a preparatory period of nearly two years in Uppsala, including education and work, mainly in language, botany and history, preparing him as thoroughly as possible for the many aspects of his voyage to the Middle East in the 1760s.

Adam Afzelius (1750-1837) was the final of the so-called apostles, who mainly observed botanical matters more than 20 years after Linnaeus’ lifetime. Before his journey to England in 1789, he had a travel pass arranged at Lands Cancelliet in Göteborg, which made it probable that he boarded a ship destined for London in this busy Swedish harbour city. He unintentionally came to stay longer than planned in London, as noted in a letter to his brother Johan Afzelius (1753-1837) dated 8 April 1790. Due to this lengthy stay, he mentioned that everything was more expensive than expected and despite being cautious with expenses, he had managed to live on 250 Daler in copper coins [Rixdollar copper coin] during eight months. Still, he estimated that he would have no money left the following month.

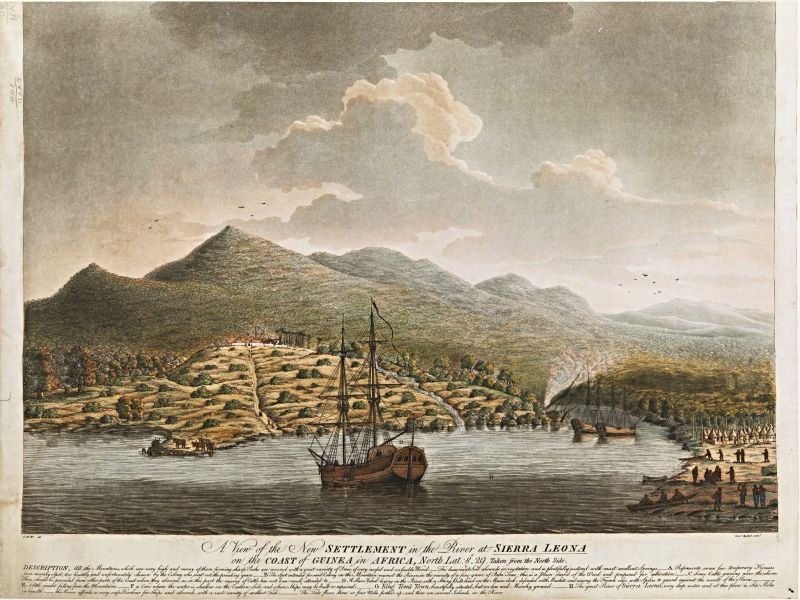

In March 1792, Adam Afzelius received the following instructions for his Sierra Leone journey embarking from England: ‘Afzelius original contract with the Sierra Leone Company was for a period of no more than two years. He was allowed free passages there and back, a house and provisions, a European servant, and apparatus. If he discovered anything of material advantage to the company, he would have a “handsome donation”; no mention was made of a salary.' However, he had to return to England the following year on the grounds of ill health, and a second scientific journey to the same area was undertaken in the years 1794-96.

This print, dated circa 1790, gives an additional view of the colony of Sierra Leone and the surrounding mountainous landscape where Afzelius and his assistants made fieldwork observations. It is an idealised European view or even a future wishful contemplation, focusing on the calm atmosphere and several abandoned slave ships in the bay. The aquatint is also believed to have been based on a drawing by the abolitionist Carl Bernhard Wadström (1746-1799), which further explains the mood of this coloured drawing. (Courtesy: British Library, Topographical Collection, Maps K.Top.117.110. Public Domain).

This print, dated circa 1790, gives an additional view of the colony of Sierra Leone and the surrounding mountainous landscape where Afzelius and his assistants made fieldwork observations. It is an idealised European view or even a future wishful contemplation, focusing on the calm atmosphere and several abandoned slave ships in the bay. The aquatint is also believed to have been based on a drawing by the abolitionist Carl Bernhard Wadström (1746-1799), which further explains the mood of this coloured drawing. (Courtesy: British Library, Topographical Collection, Maps K.Top.117.110. Public Domain).Exactly how Adam Afzelius's continuous financial planning worked out is unknown, but like several other Swedish naturalists before him, he worked for Joseph Banks. Evidently, in 1790, Afzelius worked with a transcription of ‘Dr Montin’s travels to Lapland in 1749’ (the botanist Lars Montin (1723-1785) was also one of Linnaeus’ former students), to be kept in Banks’ home library at Soho Square in London. A home and “natural history workshop”, which came to be a meeting place for naturalists and enlightenment circles over a forty-year period.

Sources:

- Afzelius, Adam, Sierra Leone Journals 1795-96. Ed. by Peter Kup, Uppsala 1967. [pp. 1-2] & Travel pass [Nordic Museum…No. NM.0073136] & Letter to Johan Afzelius & Transcription of Montin’s journey [Uppsala University Library, No: 16444 & 103088/Alvin online]. & Information about the link of this print to Wadström’ [British Library…K.Top.117.110].

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771, 2 vol, Sydney 1963. [Vol. One. p. 153].

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012 (Quotes from the journals of the Linnaeus Apostles).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 205 & 389-390).

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, Sweden. (M 292: ’En kort beskrifning uppå en Ostindisk resa till Canton uthi China. Förrättat af Carl Fredrich von Schantz Ifrån åhr 1746 Till åhr 1749.’)

- Linnaeus, Carl… Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. Ed. Roger Jacobsson, vol. II., Umeå 2003 (pp. 318-330).

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Rejsebeskrivelse fra Arabien og andre omkringliggende lande (Intr., Michael Harbsmeier), København 2003. [Introduction].

- Phipps, Constantine John, A Voyage towards the North Pole undertaken by his Majesty’s Command 1773, London 1774 (pp. 11-1)].

- Skottsberg, Carl, ed. Pehr Kalms brev til Samtida: 2, Pehr Kalms brev till friherre Sten Carl Bielke, Helsingfors 1960. [Quotes in translation from letters dated 8 Nov 1745, 3 June 1746, 2 July 1746, 3 April 1747, 13 Oct 1747 & 18 Nov 1747].

- The Linnaean Correspondence. Information & quotes, translation from Swedish: Letter L0728: Bäck to Linnaeus, 9 Oct 1746 & Letter L0730: Linnaeus to Bäck, 30 Sept 1746 & Letter L1020: Linnaeus to Lidbeck, 1 April 1749 & Letter L1024: Linnaeus to Tessin, 15 March 1749 & Letter L2497: Alströmer to Linnaeus, 19 Dec 1759.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE