ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

THE STORY No. 2 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Chests, Trunks and Bags during Naturalist Journeys

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

Setting out on a journey that would take several years required the methodical packing of personal belongings, both for daily life and for any eventuality that one was liable to encounter in various climates. The essential requirement for storage was a solid and watertight chest. These were mainly made of wood with a lid that could be locked to secure the valuable contents against dampness, direct sunlight, insects and theft. The practical aspects related to all sorts of luggage on lengthy travels varied depending on one’s economic means and mode of transport. Everything from the fundamental needs to a dandyish or a more comfortable lifestyle during travels may be seen and deciphered from journals, correspondence and other documents. This essay will look closer into this necessity from a global 18th century perspective via a wide selection of sources – starting with a uniquely well-preserved chest.

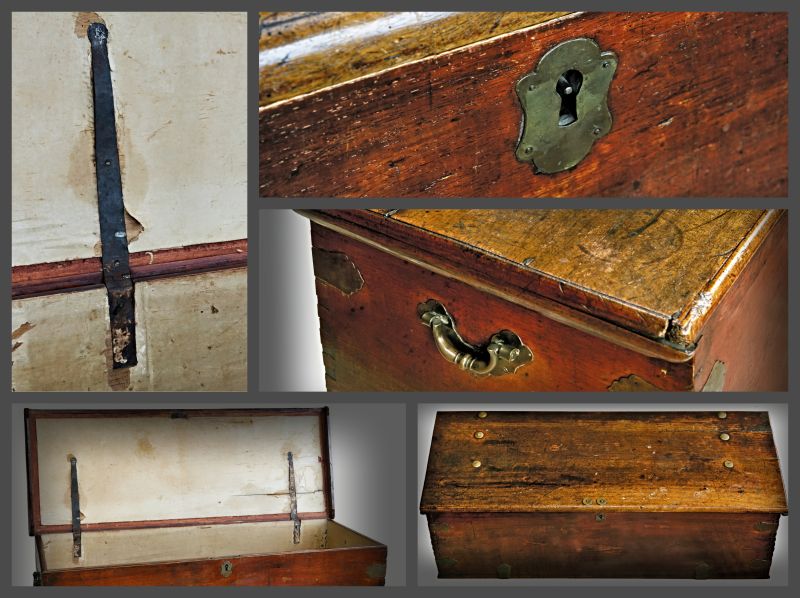

-900x534.jpg) Linnaeus apostle Pehr Osbeck’s (1723-1805) well-preserved wooden chest. | The corners are reinforced with decorative brass fittings; the bottom is reinforced in the same way. The chest can be lifted with the help of two strong handles of cast brass mounted on the ends with fittings of sheet brass. The upper edge of the chest is grooved, and the lid is tongued so as to slot neatly into place. Exact measurements of the chest are 159 cm x 62 cm, and the height, including the lid, is 59 cm. Its shape is perfectly straight, and the sides have dovetailed corners. No joints on either lid, side or bottom are made from mahogany wood, 2.5 cm thick. Photo: The IK Foundation, London, UK (Private ownership).

Linnaeus apostle Pehr Osbeck’s (1723-1805) well-preserved wooden chest. | The corners are reinforced with decorative brass fittings; the bottom is reinforced in the same way. The chest can be lifted with the help of two strong handles of cast brass mounted on the ends with fittings of sheet brass. The upper edge of the chest is grooved, and the lid is tongued so as to slot neatly into place. Exact measurements of the chest are 159 cm x 62 cm, and the height, including the lid, is 59 cm. Its shape is perfectly straight, and the sides have dovetailed corners. No joints on either lid, side or bottom are made from mahogany wood, 2.5 cm thick. Photo: The IK Foundation, London, UK (Private ownership). While the lid of Pehr Osbeck’s chest has been painted in slightly varying glossy varnish compared to the rest of the chest, and three decorative arched brass fittings on either side are linked together with the long slim hinge fittings on the inside of the lid. The lid fitted tightly was essential so that damage caused by humidity, grime, harmful insects and vermin could be minimised. The lock mechanism, seen from the inside, is made of iron with brass exterior fittings. The key to the chest is missing. During a voyage, the chest was, in all likelihood, the only portable storage container that could be locked, and therefore, the construction and durability of the lock were crucially important. Photo & Collage: The IK Foundation, London, UK (Private ownership).

While the lid of Pehr Osbeck’s chest has been painted in slightly varying glossy varnish compared to the rest of the chest, and three decorative arched brass fittings on either side are linked together with the long slim hinge fittings on the inside of the lid. The lid fitted tightly was essential so that damage caused by humidity, grime, harmful insects and vermin could be minimised. The lock mechanism, seen from the inside, is made of iron with brass exterior fittings. The key to the chest is missing. During a voyage, the chest was, in all likelihood, the only portable storage container that could be locked, and therefore, the construction and durability of the lock were crucially important. Photo & Collage: The IK Foundation, London, UK (Private ownership).The outside of a travel chest was sometimes completely covered with leather – often named as a trunk, but not consistently, giving some design uncertainty. Trunks could also be leather only, as yet a barrier against water. Iron, brass or other metallic fittings on the edges and corners were vital to protect the chest or trunk as they protected the contents during rough handling. Such models were often made wider at the bottom than at the top, which made them suitable for standing on the deck of a rolling ship without tipping over. Furthermore, the lid was flat so that it could be used for sitting or lying on.

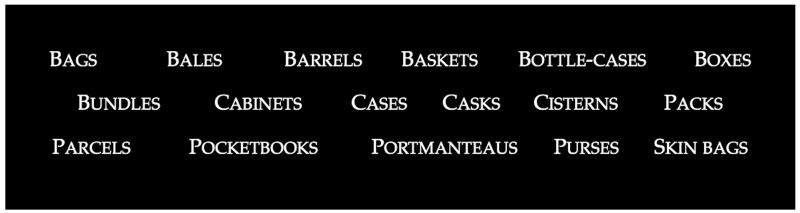

According to correspondence, journals, receipts, physical objects, etc., a multitude of other methods for safekeeping and storing one’s luggage and collections during lengthy travels also included the following…

According to correspondence, journals, receipts, physical objects, etc., a multitude of other methods for safekeeping and storing one’s luggage and collections during lengthy travels also included the following…It is important to emphasise that these, often young naturalist travellers were not a unified group of people, due to that they came from various backgrounds with widely differing socio-economic circumstances. Such contrasts could be visible in how they referred to their new purchases of particularly fashionable garments or repeatedly noted the lack of suitable clothes, which often mirrored the number of trunks, bags and other luggage in use. Equally, the number of servants or assistants helping out with daily tasks relating to the naturalists’ personal belongings, etc., also gives some clues to the possibility of travelling comfortably. At the same time, common for all was the importance of keeping baggage and collections dry and safe to best assist all needs during travels lasting for years. However, the state of each and everyone’s luggage did not only depend on one’s personal financial situation when setting out on a journey – as various grants, as well as financial aid from benefactors, academies and other interested individuals or organisations, could assist in immediate costs for the acquiring of trunks and other necessary practicalities, but also for repeated expenses linked to the transport of luggage and collections. A further aspect was to remember where each and every item was stored to avoid moments of not finding what you were looking for. Whether you keep your luggage in good order or less so obviously differed from one individual to the next, depending on factors such as personality, financial means, way of travel, climatic conditions, assistants or servants etc. It may also be assumed that even the most untidy traveller – during lengthy periods stretching over months and often years – either got used to his disorderly packing or developed more tidiness along the way to ease his everyday needs and fieldwork.

All sorts of trunks, chests, and other packing methods listed above could be ordered/purchased close to home in a shop or market or handcrafted models in the home country before setting off on a journey. Journals, diaries, and correspondence also reveal that preparation for personal belongings and collections was often an ongoing process, even throughout the actual natural history expeditions. Pehr Kalm’s (1716-1779) travelling account written during his journey to Norway, England and towards the North American colonies from 1748 to 1751 is the most detailed account of such continuous planning. These regularly kept notes demonstrate how an 18th century traveller could make it more manageable to look after, keep safe, buy goods, find suitable workers or carpenters, carry belongings or send luggage in advance simultaneously, following one’s scientific instructions and making all other practical goals possible. Hand-written or printed contemporary sources give additional clues to the complex web of traded goods related to personal luggage and collections, either made locally at visited places or imported from neighbouring or far-flung countries. For many, the price was often an obstacle as expensive articles or transporting methods may have been out of their reach. So, looking for “ordinary pricing” was an excellent way to keep within one’s means as a naturalist when making required investments in the long travel process – prior to, during and after alike.

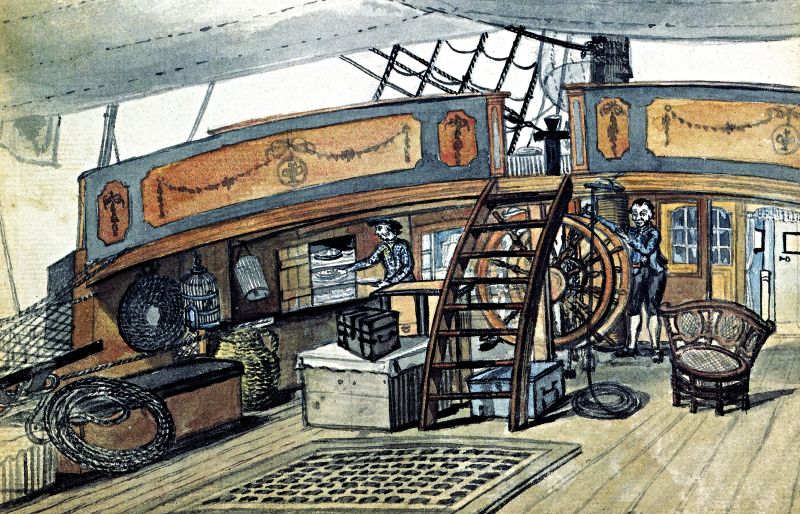

Chests, other storage receptacles, cupboards, etc., under the sundeck on a Dutch East India Ship, painted by Jan Brandes in 1778. The details of the men’s clothing elude close study, but knee-breeches, short jackets, white stockings and dark shoes and one of the men is wearing a hat of blue cloth. Maybe the persons portrayed are the first mate and the captain. The Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) travelled on just such a Dutch ship on his return voyage from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the Netherlands that same year. His experiences of the sundeck of the ship were probably not dissimilar to this depiction. (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Chests, other storage receptacles, cupboards, etc., under the sundeck on a Dutch East India Ship, painted by Jan Brandes in 1778. The details of the men’s clothing elude close study, but knee-breeches, short jackets, white stockings and dark shoes and one of the men is wearing a hat of blue cloth. Maybe the persons portrayed are the first mate and the captain. The Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) travelled on just such a Dutch ship on his return voyage from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the Netherlands that same year. His experiences of the sundeck of the ship were probably not dissimilar to this depiction. (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands).If going on long-distance voyages, a great advantage was to have a cabin, giving room for luggage and collections. An example of such an arrangement was mentioned in a letter from the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) to his friend Count Sten Carl Bielke (1709-1753) on 13 February 1746, regarding the very first apostle, Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746), when he on this day left Göteborg harbour onboard a Swedish East India Company ship towards Canton as a ship’s chaplain. Linnaeus wrote: ‘that “our” Chinese priest has got better lodgings on the ship and another chest.’ Among the travellers who gave the most particular information about cabins and luggage onboard was the wealthy Joseph Banks (1743-1820), accompanied by his natural history assistant Daniel Solander (1733-1782), the artist Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) et al. on James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage from 1768 to 1771. Even if onboard or staying for periods along the route, they lived as gentlemen: servants packed their luggage, and they were called upon when it was time to travel; overall, one’s expectation to be served in all conceivable ways seems to have continued as usual during such a lengthy sea voyage. It is also essential to see Banks, via his journal and extensive correspondence, from the perspective of a very wealthy individual who belonged to the aristocracy. This group in society during the second half of the 18th century (just as earlier and later in time) often regarded themselves as above most ordinary people who worked manually in one way and another. If this way of regarding oneself was a reason for him to engage many people in his works over the years – also including a botanist like the former Linnaeus student Solander and several ambitious students – is uncertain. Perhaps it was only his wealth that made him unwilling to work with practical tasks, or maybe he realised his weaknesses and employed the correct individual for each task during his long life to receive the best result possible. Banks himself was primarily a collector, and when it came to natural history collections, it seemed to be an ongoing challenge to handle, preserve, and transport these heavy loads versus light luggage. Two quotes and some information from his extensive journal may further support these thoughts.

On 25 October 1768 in the Atlantic Ocean, the tropics – Banks not only described the difficulties with mould but also what material their trunks, etc., were made of: ‘…upon all kinds of furniture: everything made of Iron rusted so fast that the knives in peoples pockets became almost useless and the razors in cases not free. All kinds of Leather became mouldy, Portfolios and trunks coverd with black leather were almost white, soon after this mould adhered to almost everything, all the books in my Library became mouldy so that they were obligd to be wiped to preserve them…’ A totally different perspective on personal belongings was the so-called ‘merchandise’, mentioned on more than one occasion. This meant they brought minor presents or bartering goods kept in their trunks, like beads, ribbons, and nails, which were convenient to sell or barter. Judging by a note on 15 January 1769 at Terra del Fuego, it is also evident that Banks had several men at his assistance with heavy loads during fieldwork trips: ‘This morn very early Dr Solander and myself with our servants and two Seamen to assist in carrying baggage, accompanied by Msrs Monkhouse and Green…, set out from the ship to try to penetrate into the country as far as we could…’ Furthermore, after returning safely home to England after three years, correspondence between Banks and the Earl of Sandwich, a memorandum from the Navy Board, etc., revealed advanced plans and wished to be part of James Cook’s second voyage starting in 1772. Necessary equipment, accommodation for ‘myself and my people’, the engagement of an artist, six domestic servants (also assisting with collecting work) and vast quantities of baggage were some of the matters and obstacles discussed. Despite Banks’ wealth and favourable position in society, his unrealistic demands of spacious accommodations onboard were not feasible, and a second circumnavigation never took place for him and his assistants.

Via the Swedish East India Company, also trading with India, but even more with China, a book of copied letters for the ship Hoppet from 1751 to 1754 reveals details about the transport of chests and boxes. One of the copied letters was dated ‘Canton 10 November 1753’, at the time when the ship had been loaded for its return voyage with goods ordered by the company and for some individuals’ accounts. Furthermore, it seems like these wares included orders from captains, directors and supercargoes of the company not taking part in this particular voyage themselves:

- ‘For Mr Campbell [Director]; 1 Clothing Chest, 1 Writing Box…’.

- ‘For Mr Engelhardt [Captain]; 1 old Chest with clothes…’

- ‘For Mr Paulin [Supercargo]; 1 Clothing Chest, 2 Bundles with linen clothing…’.

This suggests that chests and boxes of various kinds were not necessarily part of the existing crew’s possessions or merchandise belonging to the company itself. A complex network of linked individuals also used every opportunity for private commerce or sending commodities to and from Asia.

In this book of copied letters, Claes Grill (1705-1767) was part of the same East India trading partners as his name was included in a letter dated ‘Cadix 4 March 1752’. Due to his wealth, as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and as one of the directors of the Swedish East India Company, he can also be linked to thirteen individuals in the Linnaean network. Either via private and professional meetings or correspondence. One of them was the apostle Pehr Osbeck, who travelled to Canton from 1750 to 1752 as a ship’s chaplain for the company on Prins Carl. In his journal, he extensively described the heavy wood travelling chest he had acquired. On 2 September 1751, during his stay in Canton, he further informed of its usefulness, size, etc.: ‘For putting my clothes into and to lie upon during the homeward journey, I bought myself a chest of that wood, which was 2 1⁄2 ells long and 1 ell wide, coated in brown varnish and with brass escutcheon and furniture, for 100 Daler K:mt (Rixdollar copper coin).’ This very chest has been traced and is still in good condition, which can be seen in the introduction image of this essay. Osbeck also recorded how functional a chest could be to a traveller after his return to Sweden, something he wrote in a letter to Carl Linnaeus on 18 August 1752. He first apologised for the delay in sending the letter because of illness and that conditions had not been the best as he had lived ‘in a dark and stifling cabin and was plagued by disorder in a chest that had served as a bed, wardrobe and storage space for my specimens.’ In other words, Osbeck slept on his chest lid while his clothes and the natural history rarities he had collected were stuffed inside it.

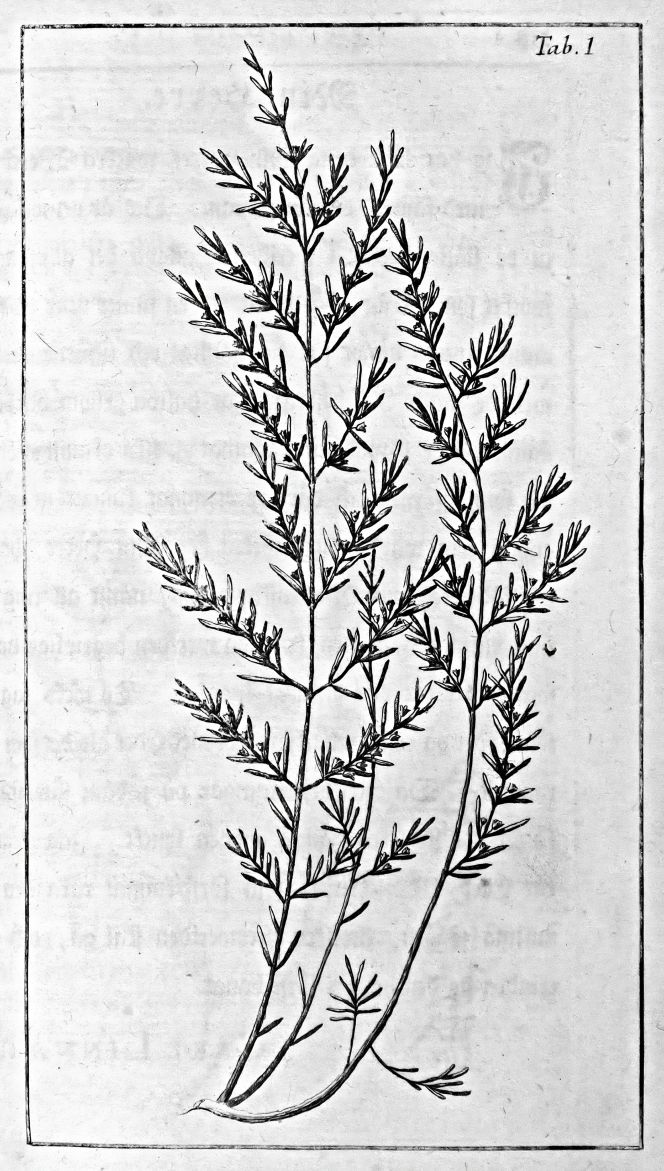

The moth-resistant plant Baekia frutescens was not only described in Osbeck’s journal but also shown in an illustration enclosed in an edition printed in 1771. He had also discovered that this useful plant kept his clothes free from moths during his homeward voyage. In his chest were kept not only his clothes but, most likely, all the private belongings of value that he had brought with him. (Illustration in Pehr Osbeck’s journal printed in an English edition 1771).

The moth-resistant plant Baekia frutescens was not only described in Osbeck’s journal but also shown in an illustration enclosed in an edition printed in 1771. He had also discovered that this useful plant kept his clothes free from moths during his homeward voyage. In his chest were kept not only his clothes but, most likely, all the private belongings of value that he had brought with him. (Illustration in Pehr Osbeck’s journal printed in an English edition 1771). During the same decade in South America, another of Linnaeus’ former students made some notes about his belongings. When Pehr Löfling (1729-1756) travelled overland in order to enhance his botanical collections, a large part of his possessions were sent by sea along the Venezuelan coast to the place where the entire expedition was to set up its headquarters. However, the ship was shipwrecked, and many of his personal items were lost. The most severe losses must have been his manuscripts, scientific instruments and other objects directly to do with his collecting work, like ‘a third of all parcels, manuscripts and other works from Cumana’ etc. being lost while others were soaked in salt water and became completely unusable. A considerable number of linen garments were also included – essential items in the humid tropical heat. According to this particular copy of a letter Löfling wrote in July 1755, the detailed list of lost personal items and collections also revealed that he used leather trunks to keep books, clothes and other essential possessions. He mentioned how these trunks had rotted and been totally destroyed when the vessel carrying his baggage foundered on its way from Cumana towards the Guayana region. Sadly, the young naturalist never quite recovered from a tropical fever and died on 22 February 1756 at a mission station at San Antonio de Caroni in Guayana, Venezuela, at age 27.

The former Linnaeus’ student Daniel Rolander (1723-1793), who also travelled to South America in the 1750s, described his luggage briefly on a few occasions from the outset of the journey in Uppsala on 21 October 1754. According to his journal, about two months later, boxes, baskets, cases, and bags were brought in the same carriage he had used himself along the roads close to Hamburg. Whilst Rolander, after a very short period in Suriname, complained that his personal belongings kept in the trunk had been infested by cockroaches: ‘In this region of the world every house is full of a great many species of cockroach. They are chiefly found where food is stored and in the clothes-chests. They gnaw on every kind of produce and, with their gnawing, shred clothing. They cause damage to everything. During my first days in this land, as I was going to bring something out of my small trunk, I found everything infested with cockroaches.’ (7 July 1755).

The Linnaeus apostle Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) had other problems with his collections and luggage as a member of Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia) during the early 1760s. For instance, in 1762, he noted high expenses and troublesome procedures for transporting all sorts of personal belongings on the boats sailing from Suez to Jeddah, taking about twenty days. The company discovered repeatedly on the journey that purchases of goods and services, which should have been straightforward from their European perspective, could often be difficult or almost impossible along the route.

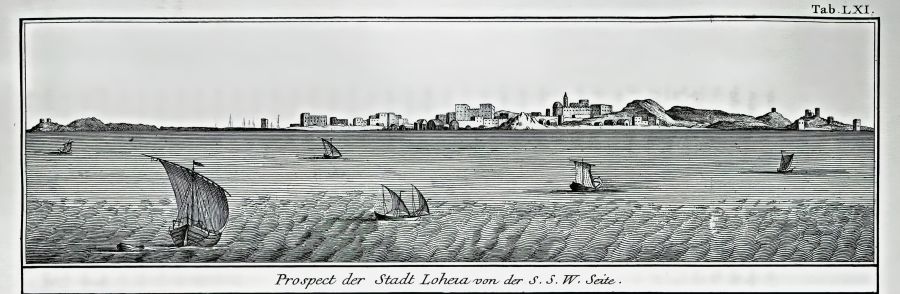

The prospect of the town of Lohaja is seen from SSW, with the typical vessels described by Peter Forsskål. | Illustration from his travel companion’s journal: Niebuhr, Carsten, Beschreibung von Arabien…1772. (Tab. LXI).

The prospect of the town of Lohaja is seen from SSW, with the typical vessels described by Peter Forsskål. | Illustration from his travel companion’s journal: Niebuhr, Carsten, Beschreibung von Arabien…1772. (Tab. LXI).One such matter was to buy an additional wooden chest in Lohaja in present-day Yemen during their stay in the area from December 1762 to February 1763. In a negative and somewhat derogatory tone, Forsskål noted in his journal: ‘The scarcity and expensive nature of iron equipment is evidence enough of the miserable condition of factory manufacture and handicrafts in this country; in fact, it is to a large extent altogether unknown. Products made from wood are no less rare, even though forests exist. Planks and boards cannot be found ready-made. If you want a wooden chest, tree trunks must be bought raw and newly cut down to be sawn up later, but if you want several planks from the same tree trunk, which is to say thinner ones, then the fee payable to the sawyer is as much as the value of the log itself. Even so, the resulting planks will be crooked and of very poor quality.’ Other travellers in the Arabian area and northern Africa lacked detailed descriptions of essential possessions and baggage in their journals, for example, Göran Rothman (1739-1778) during his excursions around Tripoli. On 27 November 1774, before a three-week-long journey, he wrote the following in his journal: ‘My things were the day before sent off on a camel, as the Bey had left, and followed with his and the remaining company.’ The assumption may be that he used some bag of leather or cloth instead of a heavy, large-sized trunk or chest as he was only to be away for a few weeks and that the journey was through to be full of complications. Their destination was a place in the mountains that was difficult to reach, and in certain parts, it was not even possible to ride on a mule.

On the other hand, Carl Peter Thunberg frequently referred to his trunks during the long journey in the 1770s. He gave informative details of daily life problems from the perspective of an 18th century traveller – including quarantine of luggage, unforeseen expenses and how to get heavy trunks transported and delivered close to one’s lodgings. Already from the outset, towards Holland in October 1770, he noted in his journal: ‘On the 2nd, having arrived at the little town of Bergen [Norway], we were ordered, on pain of death, not to go on shore, because the ship came from Pillaw, on the borders of Poland, and was suspected of being infected with the plague. Thought I had come as a passenger, not from Pillaw, but from Elsineur [Helsingør in Denmark], yet my trunks were brought on shore to be kept in quarantine; but the ship, with its crew, was permitted to sail to Amsterdam…’ On 9 October in Amsterdam, Thunberg had still not got his trunks and had to make an application via ‘the Swedish agent, M. Baillerie, to procure from the admiralty an order to deliver up my trunks, but all I could obtain, was a permit to get them at passing the Texel, if I should choose to take a passage for France. Thus, I was obliged to change my route and subjected to considerable inconvenience and expense.’ Even if he managed to recover his trunks after more than a month, practical matters about his luggage once again arose at his arrival in Paris: ‘November the 1st we set sail, and on the 5th arrived in the Texel, where I at last recovered my trunks by the good offices of Mr. Roseborn, our Commissary at Ausgell, at which place, all ships bound to and from Amsterdam, must be entered and cleared out On the 1st of December, in the morning, I arrived at Paris. The luggage was all unloaded and searched in the inn yard. I took an apartment in the neighbourhood to hold my baggage till I could get a lodging nearer to the colleges and hospitals in the city.’ About a year later – on 6th December 1771 – when Thunberg had returned to Texel, waiting for the Dutch East Company ship to sail towards the Cape, he mentioned the strict rules kept by the company for all personal belongings onboard. As a ‘surgeon-extraordinary’, he had the same favours as the officers, including extended space for luggage and private merchandise, which indicated that this group could ‘bring one or more large chests (besides baskets, bottle-cases, and casks of beer) as well for stowing merchandise in, as for provisions.’

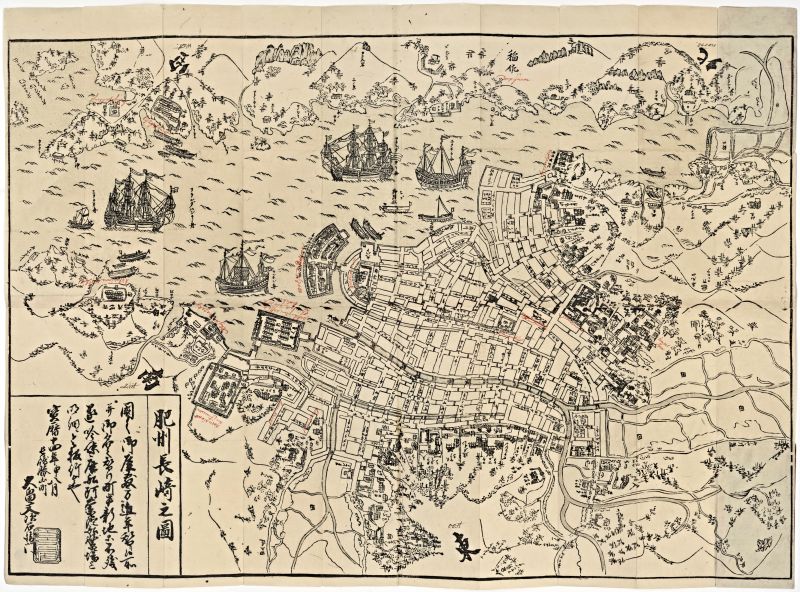

Frequent controls of Thunberg’s luggage became even more strict and time-consuming during their stay in Japan, particularly linked to contraband and goods which the Europeans desired. One such event was noted in June 1776 below the description ‘The nature and properties of the country’: ‘The norimons and the rest of the baggage, as also we ourselves, were strictly searched. It is true, I had no contraband articles to hide; but as to the scarce coins and maps, which I with great pains and difficulty had procured, I was unwilling either to lose them or, by their means, bring any man into difficulties. Therefore, after having put the maps amongst other papers, and covered the thick coins over with plaster, and hid the thinner pieces in my shoes, I arrived, with the rest of our company, safe in the factory on the 30th of June…’. The mentioned maps dating circa 1772-76, which he managed to hide and bring back home to Uppsala in 1779, are still well-preserved and kept at Uppsala University Library. This example above depicts Nagasaki with Dutch and Chinese ships in the harbour and the fan-shaped island Dezima, designated for foreign traders and visitors. These four maps were probably the total number of Japanese documents of woodblock, printed on paper, which he transported back home among his collections, the other three showing Edo (today Tokyo), Kyoto and Osaka.

Further observations from Thunberg’s voyage give glimpses into his daily life during several years in southernmost Africa and on Java. On his second journey with ox-drawn wagons in the Cape province, he noted on 11 November 1773: ‘After our wagons were brought over the water, I did not allow myself time to change my clothes, as I must have been at the pains of unpacking my trunks; but we continued our journey the whole day without farther interruption…’. Whilst on the water in the Batavia road [today Jakarta] on 18 May 1775, he mentioned that larger chests were thoroughly searched, but they ‘let trunks and chests with clothes pass untouched.’

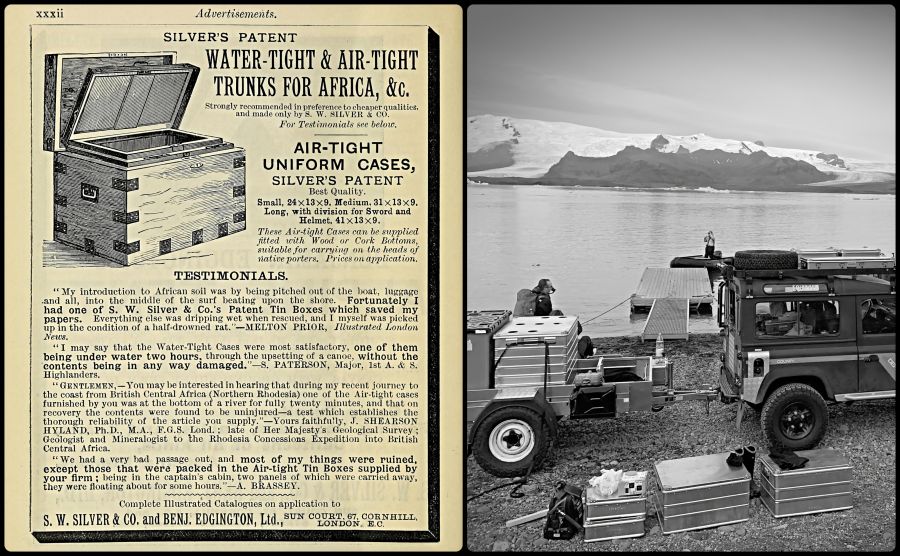

Examples of indispensable water-tight and air-tight trunks for travellers in 1901 and aluminium boxes in various sizes during fieldwork in Iceland in 2022. (Left: Coles, J., Hints to travellers, scientific and general…, 1901, p. XXXII | Right: ‘Bridge Builder Expeditions – Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland’. Photo: Lars Hansen, The IK Foundation).

Examples of indispensable water-tight and air-tight trunks for travellers in 1901 and aluminium boxes in various sizes during fieldwork in Iceland in 2022. (Left: Coles, J., Hints to travellers, scientific and general…, 1901, p. XXXII | Right: ‘Bridge Builder Expeditions – Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland’. Photo: Lars Hansen, The IK Foundation). Of course, the 18th century naturalists in the Linnaean network, like even earlier seafarers, merchants and other travellers on land and sea, needed to use practical boxes, chests, trunks, barrels, etc., containers for safe-keeping during long-distance journeys related to their work and personal belongings. From a worldwide perspective, these continuous traditions of the centuries gave ideas for improvements and technical innovations to assist daily life’s practicalities during fieldwork on several continents. Over time and even in the 21st century, many similar types of wooden boxes, linen bags, or baskets can be functional and – complemented with modern boxes of aluminium and cases of different strong plastic composites – are essential during fieldwork in various climates.

Sources:

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771, 2 vol, Sydney 1963. (Quotes & information: Vol. One. p. 178/25 October 1768, p. 218/15 January 1769 & Vol. Two. pp. 335-55).

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771, Cambridge 1952.

- Coles, John, Hints to Travellers: Scientific and General, London, The Royal Geographical Society 1901.

- Göteborg University Library (Brevkopiebok för skeppet Hoppet [book of copied letters for the ship Hoppet]) pp. 13 & 82-83).

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012 (Quotes in these journals of the Linnaeus Apostles).

- Hansen Viveka, ‘In the Chest’, The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, Volume One pp. 249-276, London & Whitby 2010.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Kalm, Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland, Helsingfors 1956.

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Beschreibung von Arabien – Aus eigenen Beobachtungen und im Lande selbst gesammleten Nachrichten abgefasset von Carsten Niebuhr, Kopenhagen 1772.

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol. London 1771

- Osbeck’s preserved chest (private ownership) has been collected with the assistance of Kristina Söderpalm. & Viveka Hansen’s earlier research: ‘In the Chest’ (2010) and the book Textilia Linnaeana…(2017, pp. 112-113).

- Rydén, Stig, Pehr Löfling. En linnelärjunge i Spanien och Venezuela. 1751-1756, Stockholm 1965 (pp. 196-197).

- The IK Foundation. | ‘Bridge Builder Expeditions – Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland’. A three-year project in cooperation with The University of Iceland and The Embassy of Sweden in Iceland (2022-25).

- The Linnean Society, London. The Linnaean Correspondence. (Summary in translation from Swedish – from the following Letter L0686: Linnaeus to Bielke, 13 February 1746 & L1465 from Osbeck to Linnaeus, 18 August 1752).

- Uppsala University Library (No: 91727/Alvin online source, Map of Nagasaki).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE