ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE STORY No. 3 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Well-prepared during Journeys

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

The advantages or disadvantages of having or not having companions must have been an adequate question long before the 18th century. Growing numbers of trunks and bags increased difficulty in finding places to stay when travelling in groups, and almost inevitable disputes were some daunting matters to take into consideration. On the other hand, favourable reasons were greater security in a group and collective knowledge, which could lead to better results. If one had the means, servants could make the journey more agreeable. It was seen as particularly useful in more than one way to engage an enthusiastic, knowledgeable student in natural history who had preferable scholarly skills in writing and drawing. On other occasions, the young man could also act as a servant. This essay will examine how 18th century naturalists tried to be well-prepared and organised on journeys.

Portrait of Olof Rudbeck the Younger by an unknown artist, probably during the 1710s. (Courtesy: Uppsala University. Public Domain).

Portrait of Olof Rudbeck the Younger by an unknown artist, probably during the 1710s. (Courtesy: Uppsala University. Public Domain).The pre-Linnaean natural philosopher Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1660-1740), during his journey to Lapland in 1695 – and later on teaching Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) at the University of Uppsala – made some detailed notations in his diary. Rudbeck travelled as luxuriously as possible for the time, with horse and carriage, stayed at inns along the Swedish coast, and was assisted by servants and students to a total of at least seven individuals – at times thirteen. Furthermore, he received 300 Daler Silver Coins from the King to “explore West Norrland for the purpose of honour and making Sweden famous”. Even if Rudbeck had the advantage of using a carriage, it was not free of obstacles as he vividly described from the most northerly visited areas: ‘…travellers come from Torne to Kimi by boat, since the traveller on that road due to the many coastal towns there in-between, it is challenging to travel fast, especially as there are no ferry-boats, so the farmers fasten a pair of their boats together, and the carriage is placed across, which delays a traveller quite substantially…’

Carl Linnaeus, on his journey to Lapland almost 40 years later in 1732, was still a student with smaller means and mostly travelled alone, by foot or on horseback and, when necessary, by boat. This reality limited his luggage and the possibility of increasing collections and specimens (except for dried plants and seeds) to take back to Uppsala at times on rough, steep and muddy roads. The journal includes brief notes only of his travelling, for example, on 22 September, ‘Arrived in the evening in Wasa’. As experienced by other travellers too, it was more expensive than initially supposed to make a long journey in the 18th century, so also for him. However, at the later part of his Lapland tour along the coast of Finland, he managed to borrow money from the vicar Fought in Torneå so he could cover the costs of staying over at the thirteen inns located between there and Åbo and other living expenses. It has also been estimated that he was a guest in vicarages and other homes along the route for approximately 65 nights. This frequently occurring hospitality of free board and lodging must have been of vital importance for the 25-year-old Linnaeus in order to be able to fulfil his scientific plan. Two years later, he embarked upon his second journey, this time to Dalarna in central Sweden. The most apparent difference was that his company, this time, consisted of seven men with varying expertise for the eight men to find out as much as possible about the botany, zoology, geology, customs and habits, way of dress, etc., of the province. An inevitable part of the ongoing planning clearly concerned the poor quality of the roads, which was noted on 13 July 1734: ‘The road was hazardous to walk, even more so to ride, altogether impossible to drive; as one block of stone lay on top of another…and no bridge existed.’ It is also evident from the journal text that they had assistance from a local man, had a good hand with the horses on treacherous pathways and rivers, as well as knowledge of the area. His Foreign Travel in 1735 started mid-winter, giving other views on travel arrangements. On 20 February, he wrote: ‘At 10 o’clock in the morning, we travelled from Falun. The night before, the snow had fallen in abundance, favouring our travel as we could use the sleigh to Nosås [!] by Örebro’. Later on, 28 April, another opportunity to travel fast in the 1730s was revealed: ‘We travelled at 6 o’clock from Lübeck with the mail-coach towards Hamburg…’

In the 1740s, Linnaeus carried out a further three provincial tours which give details about various preparation linked to daily tasks and collecting work alike: in 1741 to the islands of Öland and Gotland; in 1746 to the province of Västergötland and in 1749 to the province of Skåne. The parliament financed these three tours as they were considered politically significant in ascertaining the best developmental potential for the country’s mercantile economy, to help the start-up of more manufacturing, for instance, which could result in improved conditions for the country, as well as for its inhabitants.’ Poor roads often slowed the pace of travel caused by large stones or soft sand, which, off and on, continued to be an obstacle during these three journeys. However, one may assume that these types of obstacles were expected and planned for in advance, learned from earlier experiences by him and other travellers of the time. On 5 July 1746, during the Västergötland Journey, he noted one such problem: ‘The travel started from Borås, passed the church of Sandhult, in a westerly direction towards Alingsås: the road was a foot-path, which not without difficulty could be passed on horseback due to stones and steep hills.’ Just as it may be uncertain which planning details were made before a journey, daily chores during long travels often seem too obvious to mention or not seen as appropriate to mix with observations set out in one’s instruction. Even if each of Linnaeus’ travel journals off and on includes such practical or personal notes, like if he stayed at inns, manor houses, at farmers’ or in the open air, if he hired or used his horses, purchased food and drink, etc. This scattered information is too infrequent to give a complete picture of his daily life. One recurring theme is the kindness and assistance he received from the nobility, the priesthood, farmers and other individuals during his travels. Access to such hospitality, sleeping quarters, and valuable guidance about local plants were equally important for increasing one’s knowledge and natural history collections, staying healthy, and keeping expenses reasonable.

Re-planning was not unusual, as everything did not always turn out as anticipated. If such scenarios occurred, it was still possible to carry out at least some of the intended observations; some standard methods were to disguise oneself in local or other accepted clothing in the area, act as a physician, give bribes or negotiate with influential individuals. Obstacles and regulations for going ashore were experienced during James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage to Rio de Janeiro, resulting in their stay in the area becoming less fruitful than expected. However, according to Joseph Banks’ (1743-1820) journal, Daniel Solander (1733-1782) had more freedom to move around and collect specimens due to his profession as a physician. Solander also noted some of these matters in a letter to Carl Linnaeus, dated 1 December 1768: ‘Here we have been received with plenty of difficulties depending on the Portuguese’ fear that we in too much detail will inform about the state and products of the country, so we have been prevented from botanising and collecting insects in the countryside.’

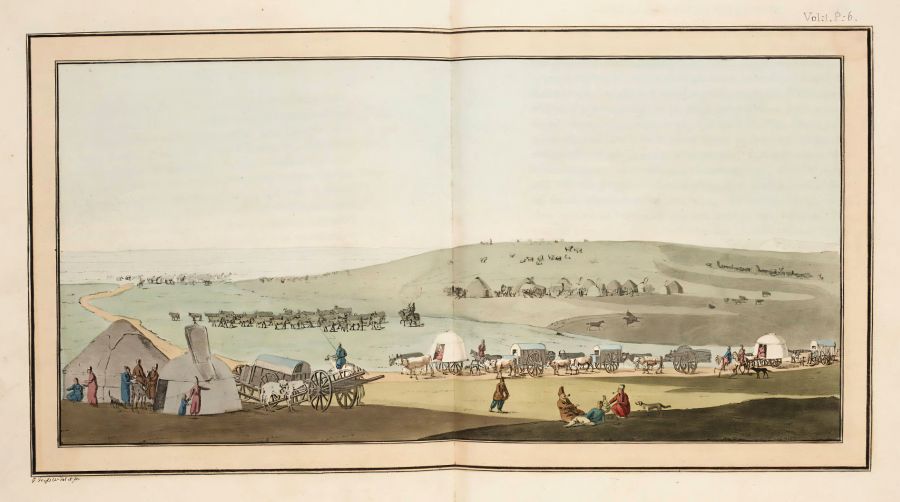

Travellers with natural history as their main aim in the Linnaean network made practical preparations during their time in Russia and neighbouring areas. In particular, Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811) in 1793-94 had practical local knowledge from an earlier journey when visiting the same region more than twenty years earlier in 1772. (From: Pallas… 1812, Vol. Two. Plate 6. Courtesy of: Linda Hall Library…).

Travellers with natural history as their main aim in the Linnaean network made practical preparations during their time in Russia and neighbouring areas. In particular, Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811) in 1793-94 had practical local knowledge from an earlier journey when visiting the same region more than twenty years earlier in 1772. (From: Pallas… 1812, Vol. Two. Plate 6. Courtesy of: Linda Hall Library…).Peter Simon Pallas also made a multitude of notes linked to how everyday matters could be conveniently solved, as when passing by ‘excellent springs’ on 10 May 1793 toward Astrachan, he registered on this exact spot so his guide or two local men could fetch water supplies if necessary when being in nearby dry areas. Along the route close to Volga, ten days later, the group was met with invaluable assistance (visualised above): ‘I found felt-tents prepared for us here, where we passed the night the more cheerfully, as in the neighbourhood of temporary encampments, surrounded with various herds of cattle, the gnats in a manner disappear; for at this season those insects are innumerable along the Volga, and allow no rest to the traveller, if unprotected by a proper tent…’ Pallas’ family circumstances – as a middle-aged married man accompanied by his wife and daughter (by his first wife) on a natural history journey – also give some unique and enlightening ideas of alternative arrangements. His family was left behind in towns during more physically demanding trips. Still, even so, they slowed him down, which he kindly but self-sacrificing referred to as ‘devoted to the re-establishment of my daughter’s health’ for a whole month in July 1793; he had to stay idle during the best season for collecting botanical specimens. Pallas also noted his need for interpreters was a reason for holdups, as he, on one occasion, had to wait 18 days before the language assistance finally arrived on 21 October. His time was limited this autumn as winter was creeping closer in Crimea, and the group became further delayed due to untrained wild horses, drunken peasants and priests. Along with that, their baggage wagon overturned and landed in a ditch – his attention to detail was unusual.

On his earlier journeys from 1768 to 1774, Pallas was one of the leading naturalists of the Imperial Academy of Sciences’ natural history expeditions in Russia, together with local guides, assistants, students, artists, huntsmen and translators. One of the other participants was the Linnaeus apostle Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774), who already, since September 1763, had been situated in St Petersburg as a keeper at a cabinet of natural history. During these years, he frequently complained about poor health and seems to have laid out plans for his daily life, judging by extant correspondence to Linnaeus. One may reflect on the possible effect of Falck’s ongoing poor health on his ethnographical and natural history work during the long-lasting expeditions from 1768 up to his untimely death in 1774. Gleaned from his extensive journal, observations often had to be fulfilled by one of his assistants whilst he rested, made notes and took care of collections in one of the towns along the travel route. However, Falck had already experienced disappointment in the early 1760s, when he initially had hopes of becoming an assistant on the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia in 1761, but even though Carl Linnaeus had recommended Falck for the assignment, he was not considered to be a suitable candidate.

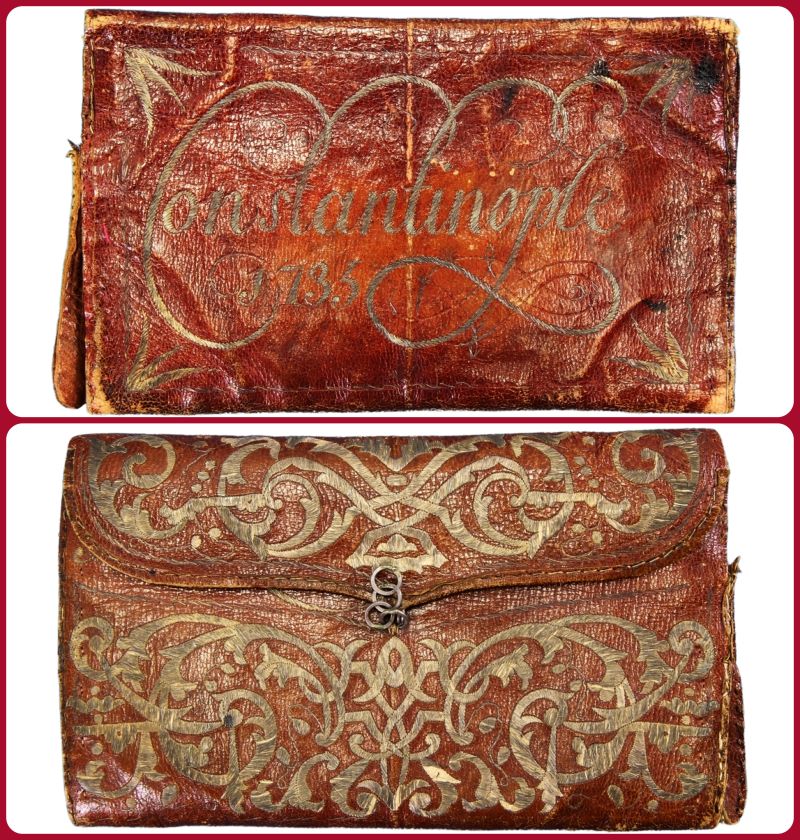

An essential part of ongoing preparations during long journeys was to make fieldwork notes to assist one’s short-term memory and for further research or publication when returning home. This well-preserved pocketbook of red saffian leather, with a silver thread embroidery reading “Constantinople 1735” and a delicate chain lock – gives several clues to 18th century travel. | Front and back, pocketbook, “Constantinople 1735” (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No. NM.0153891).

An essential part of ongoing preparations during long journeys was to make fieldwork notes to assist one’s short-term memory and for further research or publication when returning home. This well-preserved pocketbook of red saffian leather, with a silver thread embroidery reading “Constantinople 1735” and a delicate chain lock – gives several clues to 18th century travel. | Front and back, pocketbook, “Constantinople 1735” (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No. NM.0153891).This practical illustrated object once belonged to Linnaeus apostle Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752). It was probably acquired during his time in Anatolia in 1749 or 1750, when he sadly died, aged only 30, in Smyrna [today Izmir] in 1752. Subsequently, Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden (1720-1782), with the assistance of Linnaeus, redeemed the Hasselquist collection in 1754 for 14,000 Daler in copper coins [Rixdollar copper coin]. The collection comprised many natural history objects, manuscripts, antiques and ethnographic objects from the areas he visited during his travels. Among Hasselquist’s personal belongings, this pocketbook, including natural history observations from Jaffa and other visited places, was to be kept in the Queen’s cabinet at Drottningholm Palace. Later, when this Royal collection was dispersed to several Swedish museums, the pocketbook was placed at the Nordic Museum in 1925.

According to correspondence to and from Linnaeus, financial difficulties were ongoing obstacles that also affected Fredrik Hasselquist. Already a few months after the ship had left Stockholm, Hasselquist mentioned such essentials in a letter on 27 December 1749 from Smyrna. The hope was that Linnaeus, in his influential position, would like to remind Archbishop Henric Benzelius (1689-1758) about an earlier promised scholarship to be used for his natural history collection work during the journey. Linnaeus’ reply to the same letter, dated 27 February 1750, gave a pessimistic outlook on the subject: ‘I feel more than sorry, as I was not in the position to enable you any favour with money.’ In Hasselquist’s continuous correspondence with Linnaeus during this particular year, the naturalist’s search for funds was repeated, as well as other experienced practicalities and the importance of patiently waiting. On 28 February from Smyrna, he noted: ‘I have during these days received the Turkish Emperor’s travel passport, and wait every day to get an opportunity to continue my journey with a ship, which regarding statements first will sail towards Egypt’. After arriving at the destination Alexandria, his letter on 18 May passed on other preparation details. All his collections and notes made in Anatolia were left behind and kept safe at Consul Anders Rydelius’ house in Smyrna. However, Linnaeus had, over time, been successful in finding funds, which he gave an account for in a letter sent from Uppsala on 30 July 1750. It informed that the money had been collected from a group of interested men of science to assist Hasselquist’s continuous natural history journey, for a total of 3000 Daler in copper coins.

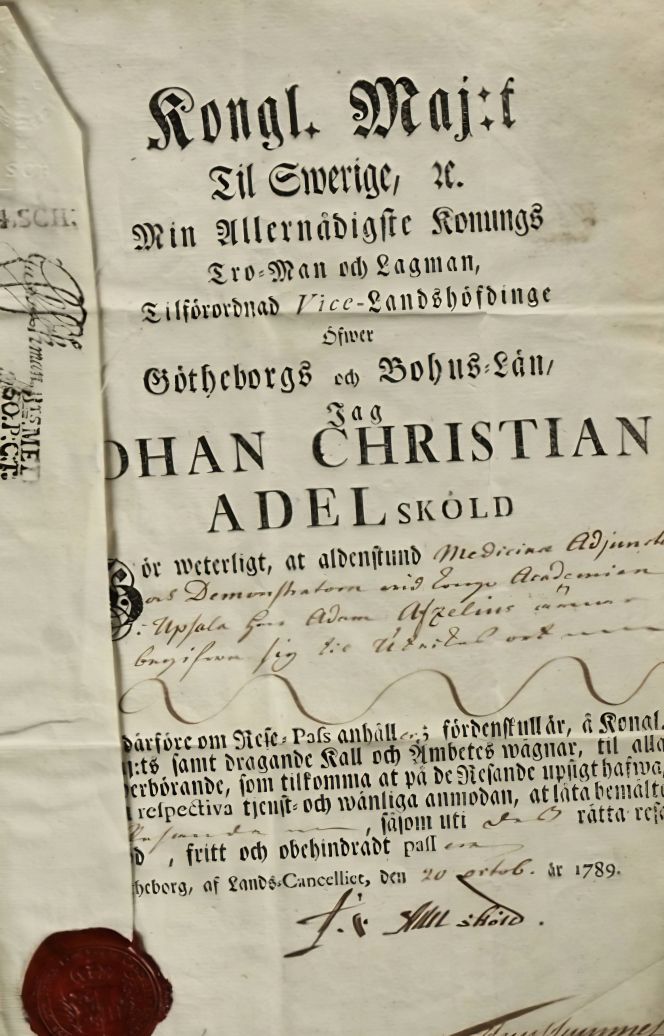

A Swedish internal passport for – Adam Afzelius’ (1750-1837) journey towards England in 1789. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0073136. DigitaltMuseum).

A Swedish internal passport for – Adam Afzelius’ (1750-1837) journey towards England in 1789. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0073136. DigitaltMuseum). This internal passport – issued by the magistrates in Göteborg and Bohuslän provinces in Sweden was drawn up for “the Medical Master and Demonstrator at the Academy of Uppsala, Adam Afzelius, who intends to travel abroad”. Such a document was needed for his journey overland from Uppsala to Göteborg before boarding a ship to England. For Swedes and foreigners who moved within the country, the strict regulations of having a passport from the authorities applied, rules which had been in place in various forms since 1555. During the time of Afzelius’ travels, at every staging post, he had to certify his intent by presenting his document to get free passage. The staging posts along the country roads were not even allowed to provide fresh horses to any traveller who did not have a passport. After several years in England (where he arrived in 1789) and two voyages to Sierra Leone – during the spring of 1796, Afzelius sailed back to London, where he stayed for a few more years after his African sojourn. His journey back home to Uppsala via Norway only started in April 1799 after almost ten years abroad, also evident via this rare and well-preserved passport dated 20 October 1789.

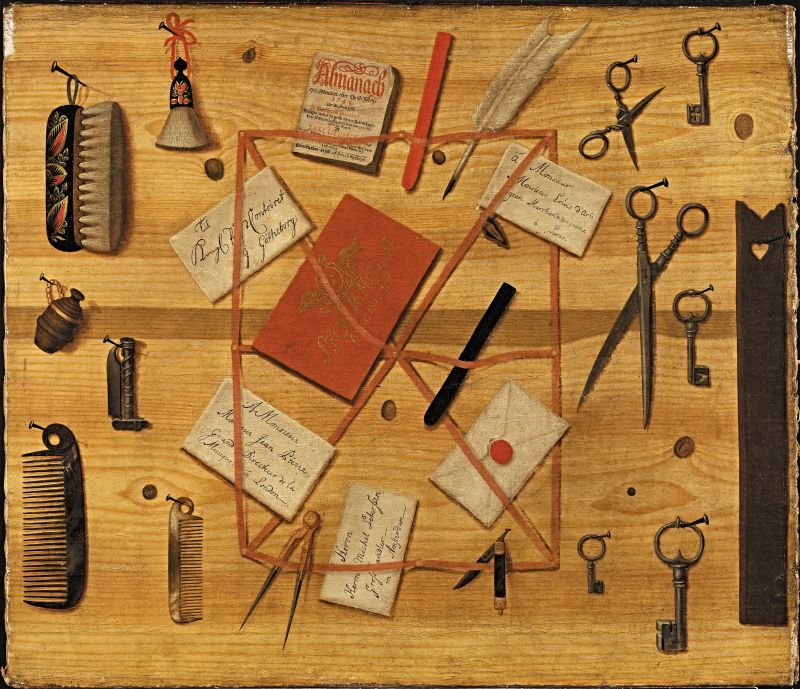

Necessities, such as being kept in a letter rack in the parlour back home, had their natural place in the traveller’s chest on the voyage. In this beautiful trompe l’œil from 1748 by the artist Hindric Sebastian Sommar, active in Sweden, some objects can be found that would be of practical use during the apostles’ lengthy research voyages for their scientific work as well as for correspondence and personal hygiene. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).

Necessities, such as being kept in a letter rack in the parlour back home, had their natural place in the traveller’s chest on the voyage. In this beautiful trompe l’œil from 1748 by the artist Hindric Sebastian Sommar, active in Sweden, some objects can be found that would be of practical use during the apostles’ lengthy research voyages for their scientific work as well as for correspondence and personal hygiene. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).All sorts of other planning and expenses were just as often an ongoing issue for natural historians on European soil, either if being part of an expedition on this continent, during a stopover in a port town or travelling over land with horse and carriage. Daniel Rolander’s (1723-1793) journal – written in Latin – includes some precise planning for his travels, including costs and likely delays (27 December 1754): ‘At some inns along the public road in Germany as well as in the cities you have to pay toll, but it is usually agreed that the payment is not made by the traveller, whose business it is, but by the one who is acting on his behalf, that is the farmer or any other who supplies the horses and carriage. Neither are the affairs of the travellers investigated, nor are their boxes, cases, baskets, or bags opened. Still, the toll is paid according to the number of travellers or according to the number of pieces of luggage and their weight. However, they are seldom weighed. As I have mentioned above, the public roads gave the travellers quite a lot of trouble to overcome because the necessary repairs were not being done, which once again delayed us, so that late in the evening, we had to set the limit for this day’s trip at a farm named Winckeldorff, nine leagues from Hamburg.’ Whilst several of the natural historians visiting Cadix and neighbouring areas in Spain complained and were surprised about the tremendous expense one had to take into account if staying in this place. For instance, Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746), after a stay in the close-by situated Port Marie [El Puerto de Santa María] on 7 April in 1746, noted in his journal: ‘My good and god-fearing wife did not receive so much in ready money when I left her for the two- to three-year voyage as I spent over these six days.’ The contemporary East India traveller Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765) made a similar observation in his journal, February 1747, in Cadix: ‘They [local citizens] willingly lodge, but take very much in payment’.

Before the ships sailed from Cape on 22 November in 1772, the assisting botanist Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) noted the following in his journal: ‘Moreover, for the specific benefit to science from this voyage, the following – Joh. Reinh. Forster (1754-1794), father, and his son Mr Georg Forster (1729-1798), the astronomer Mr William Wales (1734-1798), and the landscape painter Mr William Hodges (1744-1797) - were engaged to the ship Resolution, commanded by our commander Captain Cook (himself the 112th person).’ In this watercolour, the accompanying painter, William Hodges, depicted the scene of the two ships, the Table Mountain and Cape – a bustling harbour town where extensive preparations had taken place almost one month prior to the continuing sailing in a southerly direction. Watercolour by William Hodges on James Cook’s 2nd voyage 1772-75. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Safe/PXD 11. IE9611721. FL9611886).

Before the ships sailed from Cape on 22 November in 1772, the assisting botanist Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) noted the following in his journal: ‘Moreover, for the specific benefit to science from this voyage, the following – Joh. Reinh. Forster (1754-1794), father, and his son Mr Georg Forster (1729-1798), the astronomer Mr William Wales (1734-1798), and the landscape painter Mr William Hodges (1744-1797) - were engaged to the ship Resolution, commanded by our commander Captain Cook (himself the 112th person).’ In this watercolour, the accompanying painter, William Hodges, depicted the scene of the two ships, the Table Mountain and Cape – a bustling harbour town where extensive preparations had taken place almost one month prior to the continuing sailing in a southerly direction. Watercolour by William Hodges on James Cook’s 2nd voyage 1772-75. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Safe/PXD 11. IE9611721. FL9611886).After working as an assisting botanist on James Cook’s second voyage, Anders Sparrman had finalised his assignment when the ship returned to the Cape on 22 March 1775. He is also an individual who may be studied from the perspective of financial insight, as he almost immediately started to make preparations for an African Expedition further into the countryside in southernmost Africa. This journey lasted for nearly a year. Sparrman did not complain about unreasonable prices in the Cape, though, probably because he had some money saved up before this voyage – received via scholarship and his employment as a tutor during the first period in Cape 1772. He also made a note in November this year that Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg had been appointed by the British Crown and been paid ‘8000 ducats for the whole expedition’, whilst Sparrman modestly noted that they ‘offered me my voyage gratis’ on the ship Resolution. One may assume that he received some financial reward or succeeded in making minor private trade during Cook’s voyage, judging by his immediate possibilities to make extensive purchases in the Cape. His continuous planning was noted in the journal, particularly from March to April 1775, including expenses like taking on the assistant Daniel Immelman, buying a new wagon with a tilt made of sailcloth, five pairs of oxen to draw the wagon, medicines, small stock of bartering goods like glass beads and tobacco, necessary equipment for natural history collecting, tea, coffee, chocolate, sugar, gunpowder etc. Sparrman also revealed how they prepared for the best possible sleep during the first part of this trip over land, as recorded in his journal (25 July 1775). Most nights, they slept on the bare ground or under the wagon with ‘a saddle for my pillow and great coat to cover me from the cold of the night.’ They took extra precautions during bad weather: ‘When it rained, we lay in the tilt-waggon itself. Here, on account of our baggage, we were still worse off. The best place I could find for myself was my chest, though even that had a round top: Mr Immelman, being slender and less than me, was able, though not without great difficulty, to squeeze himself in between my chest and the body of the wagon, where he lay on several bundles of paper.’

The receiving of letters of recommendation also had to be planned, not only prior to starting off but also along the actual journey. Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828), also stationed in the Cape province in the mid-1770s, made such ongoing preparations. Just before the Dutch East India Company (VOC) ship sailed from the Cape towards Java, he noted on 2 March 1775 in his journal: ‘I now received from Amsterdam not only a sum of money, but also letters of recommendation to the Governor-general Vander Parra at Batavia, in consequence of which I had to prepare for a voyage to the East Indies, and as far as the empire of Japan. In the three years I had passed in the southern parts of Africa,…’

![Print of the City of Batavia… [today Jakarta] circa twenty years before Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit, dated 1754. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 87807. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/7a-batavia-1754-800x661.jpg) Print of the City of Batavia… [today Jakarta] circa twenty years before Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit, dated 1754. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 87807. Public Domain).

Print of the City of Batavia… [today Jakarta] circa twenty years before Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit, dated 1754. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 87807. Public Domain).Upon the arrival at Batavia on 18 May 1775, Carl Peter Thunberg once again referred to the importance of such letters, of making friends and financial proceedings that must be taken care of: ‘Besides the letter of recommendation from Dr Le Sueur at the Cape, I had borrowed a sum of money from that gentleman to pay the debts I had contracted there, which sum I had engaged to pay to Dr Hoffman out clearly that I was not one of those travellers who had amassed Indian riches, and that during my three years stay at the Cape I had been more successful in accumulating plants and natural curiosities than gold. This he also mentioned to M. Radermacher, whose physician he was, and this gentleman immediately gave him fifty ducats for me, before I had had time to wait on him, and even before he was become personally acquainted with the man, for the narrowness of whose circumstances he felt so nobly.’

Thunberg again noted planning for financial circumstances in his journal (1-3 June 1775). When the ship was preparing to leave the harbour of Batavia towards Japan, he got a tempting offer to remain in Batavia and take up a well-paid vacant position as a physician, paying 6 or 7000 Rix dollars yearly. However, Thunberg thanked his benefactor, M. Radermacher, for the kind offer but preferred to continue as planned and to keep his promise made in Holland with his intended voyage towards Japan.

A link to Java and Carl Peter Thunberg was C.F. Hornstedt (1758-1809), a disciple of Thunberg after his nine-year-long journey from 1770-79. Hornstedt wrote his travel diary in “letter form” addressed to his former teacher, intending to publish it in diary form, from his journey to Java in 1782-86. Still, the text was compiled after his return to Sweden (first published in 2008). He travelled with the Swedish East India Company on the out voyage, and a Swedish ship named Concordia sailed to Amsterdam on the return. He stayed in Holland and visited Paris in 1786 before returning home. The young man, in his 20s, made some complex arrangements to make his voyage financially possible and to be able to return with extensive natural history collections. Already during the early part of the sailing, he noted on 10 and 22 January in 1783 from Göteborg that he had managed to get a free voyage to Angri – a town situated on northern Java – due to that the wealthy Baron Alströmer donated a cabinet of coins to the Society of Science (Vetenskaps-Societeten) in Batavia. He was highly pleased with the arrangements for his return from Java on 12 August 1784. His diary gives unique insights into how ongoing opportunities which evolved along the route could ease 18th century travels: ‘I travel from here with the Swedish ship Concordia to Cap bona [Cape] and further on to Amsterdam, as I should pay Mr Captain Breitholtz, for a cabin, for food and transport of 20 large boxes of natural history specimens to Holland, 1000 Dutch Guilder. But, during the journey, as a physician, I took care of the sick. Therefore, I received free transport for my 20 large boxes, free food, and a paid 1000 Dutch Guilder. Consequently, instead of paying 1000 Guilder for my home voyage, I was paid 1000.’ The year after, on 27 May 1785, Hornstedt sent 10 of these large boxes packed with natural history rarities from Amsterdam to his former teacher, Carl Peter Thunberg, in Sweden.

The importance of local guides or assistants were invaluable, not only for carrying the naturalists’ heavy personal belongings, if not on horseback or by wagon or boat, carrying them over deep waters – to assist in the natural history collecting, finding the way through dense forests, guiding with the help of the stars as well as not seldom having local specialist knowledge of plants and their uses. Several individuals within the extended Linnaean network noted such assistance in travel journals. However, despite this vital assistance in taking care of the travellers’ possessions and often successful in finding new species, they frequently seem to stay anonymous. They are only mentioned in passing in journals as ‘my Hottentot/Hottentots’ (Anders Sparrman and Carl Peter Thunberg in the Cape province, the 1770s). Adam Afzelius, who travelled twice to Sierra Leone in the 1790s, repeatedly included the assistants’ names in the journal for his second journey in 1795-96. For example: ‘Peter and Duffa brought following plants…’ or ‘Peter and Duffa came carrying a load of Plants as follows’ (11 & 26 January 1796). Informative details about their personal lives or belongings are lacking, and these names in Afzelius’ journal may possibly have some form of “Europeanisation”. Joseph Banks also referred to his British assistants as ‘my servants Peter and James’ or ‘my servants’ on several occasions during Captain Cook’s first voyage 1768-71, but only by their first name, so it is uncertain who these men were. Tupaia [Tupia] (c. 1725-1770), who took part in the sailing from the Society Islands to his death at Batavia, was an assistant more known than most, noted sporadically in several journals and possible to trace through his own artwork and a chart of the Society Islands with 74 visible islands – via a copy made by James Cook in 1769. Information about a substantial group of local assistants in Africa, The Pacific area or elsewhere – otherwise, to the greatest extent, stays anonymous. Journals also quite frequently mentioned Europeans (or that their relatives had moved from Europe) now living in America, Africa, etc., just with ‘Mr’ and a surname, making it hard to know more about these assisting priests, missionaries, surgeons, gardeners, farmers and others during natural history journeys in the 18th century. On rarer occasions, female individuals assisted with local facts or practicalities like ‘Mrs Muller’ who had a farm close to the Cape where Carl Peter Thunberg stayed overnight on 11 September 1773 or ‘Miss Herd’ during Afzelius’ stay in Sierra Leone on 21 January 1796 who had knowledge of the medicinal uses of some plants. Emissaries, envoys, consuls and ambassadors were another group of individuals often assisting in visiting countries; sometimes, their names were included in journals or correspondence.

Sources:

- Falck, Johan Peter, ‘13 brev 1763-1766 till Linné från Johan Peter Falck.’ Bref och skrifvelser af och till Carl von Linné I-X 1907-1943, 1912 (p. 47. Letter from Falck to Linnaeus, St Petersburg 25 February 1765).

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012 (The journals of the Linnaeus Apostles).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Hasselquist, Fredrik, ‘Brev till och från Fredrik Hasselquist.’ Bref och skrifvelser af och till Carl von Linné, 1:7. Upsala 1917, pp. 1-68 (Quotes & facts, related to Hasselquist & Linnaeus pp. 11-14, 18-19 & 23-26).

- Hornstedt, C.F., Brev från Batavia – En resa till Ostindien 1782-1786, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsingfors 2008.

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, Sweden (National Library of Sweden); ‘Dagbok hållen på Resan till Ost Indien, Begynt den 18 octobr: 1746 och Slutad den 20 Juni 1749’ by Carl Johan Gethe (M 280, p. 4).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Species Plantarum…, [two volumes], Stockholm 1753 (quotes pp. 313 & 323).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. Notes and register by I. Fries and S. Fries. Edited by R. Jacobsson, vol. II., Umeå 2003 (pp. 305-312, research about Linnaeus’ travel route, expenses, etc.).

- Pallas, Peter Simon, Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire: In the Years 1793 & 1794, 2 vol, London 1812.

- Parsons, Harriet, ‘British–Tahitian collaborative drawing strategies on Cook’s Endeavour voyage,’ Indigenous Intermediaries: New perspectives on exploration archives, ANU Press 2015, pp. 147-167.

- Sydow, Carl-Otto von, ‘Rudbeck d.y:s dagbok från Lapplandsresan 1695, Med inledning och anmärkningar 1.’ Svenska Linnésällskapets årsskrift 1968-1969, pp. 78-114.

- Sydow, Carl-Otto von, Rudbeck d.y:s dagbok från Lapplandsresan 1695, Med inledning och anmärkningar 2’, Svenska Linnésällskapets årsskrift 1970-1971, pp. 73-113 (quote p. 101).

- Sörbom, Per, ‘Over Land and Sea’, The Linnaeus Apostles: Global Science & Adventure, Ed. Lars Hansen, Vol. One, pp. 213-240, London & Whitby 2010.

- The Linnean Society, The Linnaean Correspondence. (Information & quote in translation from Swedish: Letter L6074: Solander to Linnaeus 1 Dec 1768 & Letter L1077: Hasselquist to Linnaeus 27 Dec 1749).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE