ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE STORY No. 4 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Instructions for Travelling Naturalists

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

This text aims to give insight into the wishes and orders that the 18th century naturalists had to consider as an essential part of their travel preparations. Some of these listings and text sections will be exemplified in English for the first time. Including Instructions for Christopher Tärnström in 1745, Pehr Löfling in 1751 and Göran Rothman in 1773, as well as Carl Linnaeus’ Instructions for Travelling Naturalists, printed in 1759 and the orders received by the earlier traveller Olof Rudbeck the Younger in 1695. Similar instructions have been researched via preserved correspondence and other comparable prints of the extended Linnaean network, which give additional examples of individuals in different countries. Several instructions have been transcribed and translated as close to the original handwritten Swedish texts as possible – as a part of a more wide-ranging, long-term ongoing project.

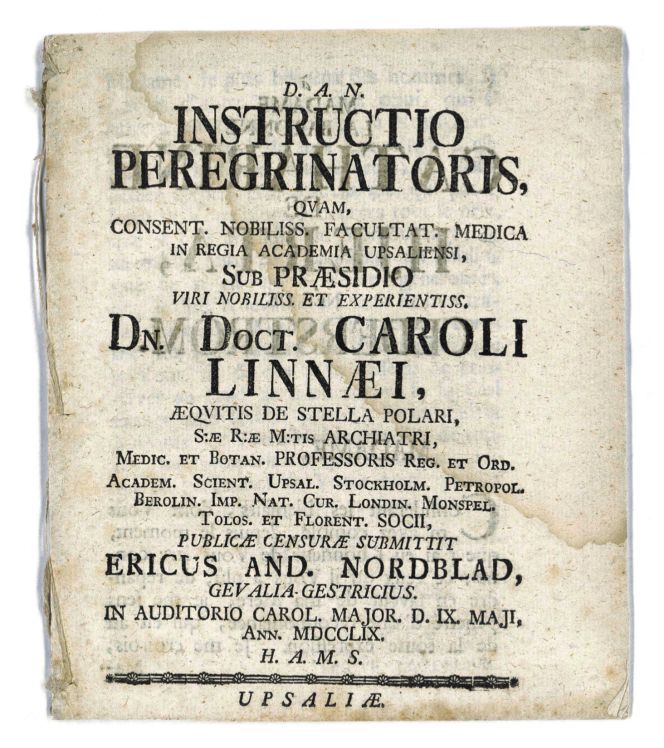

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) stands out as the person who most clearly described his preparations as to what clothes to bring on his Lapland journey already in 1732; his philosophy, on the whole, was that good planning was a “must” before any travel. Furthermore, he wrote this dissertation Instructio Peregrinatoris… (Instruction for Naturalists on Voyages of Exploration) on the subject, published in Latin 1759. | Front page illustrated here. (The IK Foundation, The Library, London).

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) stands out as the person who most clearly described his preparations as to what clothes to bring on his Lapland journey already in 1732; his philosophy, on the whole, was that good planning was a “must” before any travel. Furthermore, he wrote this dissertation Instructio Peregrinatoris… (Instruction for Naturalists on Voyages of Exploration) on the subject, published in Latin 1759. | Front page illustrated here. (The IK Foundation, The Library, London).Among a great deal of advice regarding the journey itself, geographical matters, observations of the three “Kingdoms” of minerals, plants and animals, housekeeping, diets and diseases in Instructio Peregrinatoris…, Linnaeus also emphasised that the ideal age for naturalist explorers was between 25 and 35 – ‘as he will then have reached a mature age, but does not yet have to struggle with old age.’ Time-consuming requirements, especially included: ‘Having set out on his journey and as though transported into a new world, he should consider it incumbent upon him to observe everything…’ – equally as – ‘He must never trust his often failing memory, but must immediately record all his observations in a notebook, provided this can be done without attracting attention and, until he has properly edited and written them all down on paper, he should not go to bed and sleep’ (part of §4). Two other paragraphs will exemplify his wishes further:

- §6. THE JOURNEY Distances, inns, villages, cities, towns, counties and cost of travel – everything related to all of this is usually stated by those who have travelled abroad. Any such thing as stating and directly pointing out what has been noticed in these places is also very useful for those who are to travel the same way later. I may, however, be permitted to pass over this in silence.

- §16. These are the main points to which anyone who intends to visit foreign countries should pay attention. I admit that there is a great deal more, almost beyond counting, but listing everything would go beyond the goal I had set and would exceed both my time and my not-particularly-great ability. He who in a dignified manner will have accomplished his mission concerning what has been listed above, will surely not with any justification be blamed for having dozed away in indolent rest, nor for having made his investigations in vain. No day without at least some work.’

Linnaeus, as well as other contemporary men of science, composed instructions, memoranda or wishes via correspondence, both before and after the year in this printed list of advice in 1759. For instance, Instructions still extant, which the naturalists Pehr Löfling (1729-1756), Göran Rothman (1739-1778) and Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746) received in preparation for their voyages. Instructions list the desired aims and objectives for the voyage, including raw materials, relevant practices and how best to preserve and bring back seeds or live plants. These instructions formed an essential base for the preparation of pertinent studies: for acquiring the correct type of literature, material for collecting and preserving specimens and loaning measuring instruments. Most travellers would, in all likelihood, have had some form of directive to follow, such as printed advisable lists or individual handwritten wishes in various forms or orally before the journey. In his lengthy description, Andreas Berlin’s (1746-1773) travel companion, Henry Smeathman (1742-1786), also stressed the significance of the choice of suitable garments and bedding, functional boxes, chests, medicines and other articles of importance for Europeans visiting tropical areas in the 1770s.

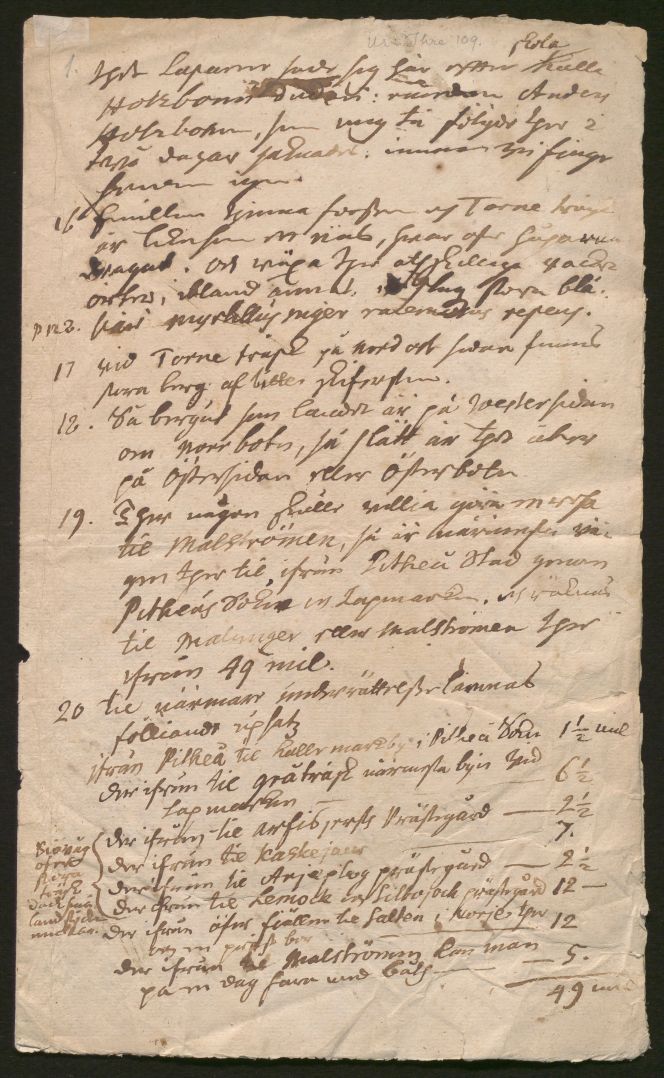

It is also worth noticing that Linnaeus had predecessors on this subject as instructions for natural history expeditions had existed already in the previous century, in particular, evidenced via Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1660-1740), who travelled to Lapland in 1695. Professor Rudbeck came to be a direct link to the extended natural history network many years later – around 1730 – as one of Carl Linnaeus’ teachers in Uppsala. Some of the matters that should be observed, listed in Rudbeck’s partly survived instruction, in this northerly situated area, were: trade in the coastal towns of Torne, Piteå, Luleå etc., if certain roads were passable with horses and to learn more about the inhabitants’ daily lives and traditions in different provinces when the travelling group passed through. His instructions listed 37 investigative points to follow. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library…Rudbeck’s Instruction. Four pages, of initially six).

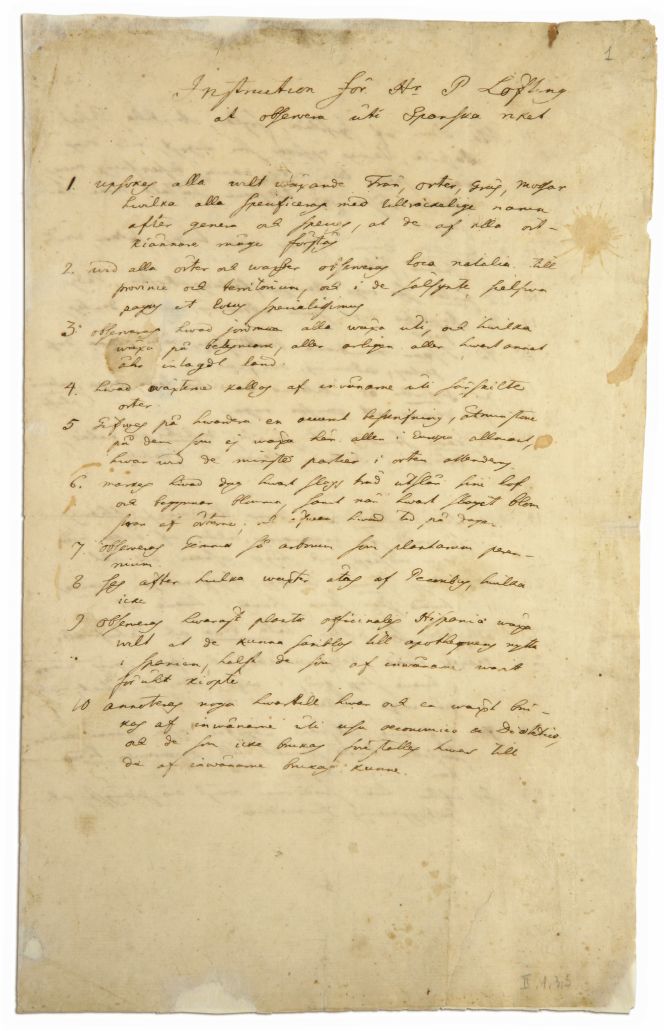

It is also worth noticing that Linnaeus had predecessors on this subject as instructions for natural history expeditions had existed already in the previous century, in particular, evidenced via Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1660-1740), who travelled to Lapland in 1695. Professor Rudbeck came to be a direct link to the extended natural history network many years later – around 1730 – as one of Carl Linnaeus’ teachers in Uppsala. Some of the matters that should be observed, listed in Rudbeck’s partly survived instruction, in this northerly situated area, were: trade in the coastal towns of Torne, Piteå, Luleå etc., if certain roads were passable with horses and to learn more about the inhabitants’ daily lives and traditions in different provinces when the travelling group passed through. His instructions listed 37 investigative points to follow. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library…Rudbeck’s Instruction. Four pages, of initially six). Whilst the naturalist Pehr Löfling received a three-page list of instructions set out in 27 points written by Carl Linnaeus prior to his travels to Spain in 1751, page one, with the first 10 points, is illustrated here and transcribed in a complete translation below. Löfling sadly died of tropical fever on 22 February 1756 at a mission station at San Antonio de Caroni in Guayana, Venezuela. His journal was posthumously published by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. (Courtesy: Centrum för Vetenskapshistoria/Centre for History of Science, Stockholm, Sweden).

Whilst the naturalist Pehr Löfling received a three-page list of instructions set out in 27 points written by Carl Linnaeus prior to his travels to Spain in 1751, page one, with the first 10 points, is illustrated here and transcribed in a complete translation below. Löfling sadly died of tropical fever on 22 February 1756 at a mission station at San Antonio de Caroni in Guayana, Venezuela. His journal was posthumously published by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. (Courtesy: Centrum för Vetenskapshistoria/Centre for History of Science, Stockholm, Sweden). ‘Instruction for Mr P. Löfling to observe in the Spanish Realms

- to seek out all trees, plants, grasses, and mosses growing in the wild, specify with sufficient names according to genera and species, that they may be understood by any botanist;

- to observe loca natalia as to province and terrain of all herbs and plants, and for rare ones, the very pagus et locus specialissimus;

- to observe in what kind of soil they grow and which ones grow on pasture or on land, fallowed annually or biannually;

- what the inhabitants in the different places call the plants;

- to give an accurate description of each one, at least of those that do not generally grow here or in Europe, paying attention to the smallest parts of the plant;

- to note on what day every kind of tree comes into leaf and begins to bloom, also when each kind of plant is in bloom, and also what time of the day;

- to observe genera arborum as well as plantarum perennium;

- to watch what plants are eaten by Pecoribus, and which ones are not;

- to observe where plantæ officinalis Hispaniæ grow wild that they may be collected for the use of the apothecaries in Spain, especially the ones previously bought by the inhabitants;

- to note down carefully to what use each one of the plants is put by the inhabitants in usu oeconomico et Diætetico, and to envisage to what application the inhabitants might put those which are not used;

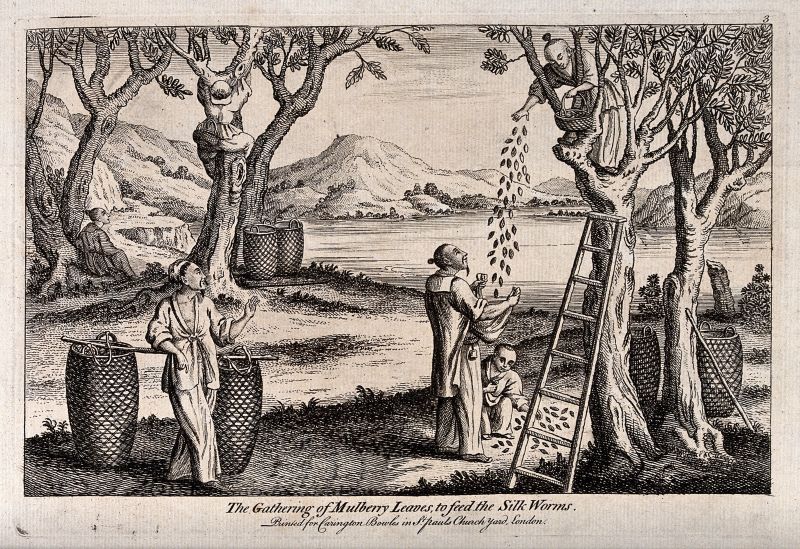

Linnaeus’ memoranda to the first of his long-distance travelling apostles, Christopher Tärnström, among many matters, listed ‘Seeds from the Chinese mulberry tree’ (no. 2 in the list below), but as Tärnström never reached China, it never came to be realised. | 18th century engraving showing; ‘The gathering of Mulberry leaves, to feed the Silk Worms’ in a silk manufacturer in China. (Courtesy: Engraving. Wellcome Collection. 44097i. Public Domain).

Linnaeus’ memoranda to the first of his long-distance travelling apostles, Christopher Tärnström, among many matters, listed ‘Seeds from the Chinese mulberry tree’ (no. 2 in the list below), but as Tärnström never reached China, it never came to be realised. | 18th century engraving showing; ‘The gathering of Mulberry leaves, to feed the Silk Worms’ in a silk manufacturer in China. (Courtesy: Engraving. Wellcome Collection. 44097i. Public Domain).Christopher Tärnström’s instructions ahead of the voyage in 1745, though, contained, among many others, the following wish in Carl Linnaeus’ given Memorandum: ‘1° To get back a tea bush in a pot or at least the seeds thereof, kept as he of me has received a verbal instruction.’ A second Memorandum given by hand to Tärnström at his departure from Uppsala, towards the East India ship in Göteborg in December 1745, also gave further instruction from Linnaeus on how to best conserve seeds from the tea plant. This included advice on various climates, seeds kept dry in waxed paper or cotton, and even some kept in fine sand, glass bottles and lead-sealed boxes. The five instructions or memorandum were initially written in Swedish to the naturalist and ship’s chaplain Christopher Tärnström, whereas the second is presented below in a complete translation. All wishes were made in writing before Tärnström’s voyage towards East India in 1745, with an introduction by the secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Pehr Elvius (1710-1749), followed by the instructions of Carl Linnaeus, Mårten Triewald (1691-1747), Johan Julius Sahlberg (1680-1753) and a final observandum by Linnaeus. Tärnström never reached China, as he died on the outward leg in December 1746, probably due to a tropical fever, at Pulo Condore [Côn Són Island] in the South China Sea. His detailed travel journal was first published in the first decade of the 21st century.

Professor Linnaeus’ Memorandum

- To acquire a tea bush in a pot or at least seeds thereof to be kept according to the oral instructions he has received from me.

- Seeds from the Chinese mulberry tree with palmated leaves.

- The many undescribed fishes that are to be found everywhere in the East Indies, to be preserved in spiritu vini and described in their natural state, for this part of the Historia Naturalis Indiae has been left to our own time and to our Academy of Sciences.

- Plants are to be collected and preserved with flowers and fruit.

- Seeds of as many plants as can be found shall be collected.

- Bulbs and tubers of the roots of lilies are to be kept in sand or moss; this also applies to succulent plants.

- Insects are to be preserved on pins, but zoophytes in spiritu vini.

- All types of snakes are wanted, especially Naja or Cobras de Capelo.

- A sample of unused clay for the making of genuine porcelain.

- The unknown drugs, Anisum Stellatum, Gummi Ammoniacum, Catechu, Lignum Aloes, and Myrobalani, should be sought, along with the tree from which they are taken and the method of fructification.

- A good botanical description of nutmeg is required.

- Ripe fruits from as many types of palms as can be found.

- Live goldfish for Her Royal Majesty.

- Measurements night and day with a thermometer south of the Equator and

Canton.

The first point in the list above can also be compared with the attempts of former Linnaeus student Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) a few years later. On the day of his return from Canton as a ship’s-chaplain-cum-naturalist, his diary included this anecdote on 4 January 1752: ‘Everyone leaped for joy, and my Tea-shrub, which stood in a pot, fell upon the deck during the firing of the cannons and was thrown overboard without my knowledge after I had nursed and taken care of it a long while on board the ship. Thus, I saw my hopes of bringing a growing tea tree to my countrymen at an end, a pleasure which no one in Europe has been able as yet to feel, notwithstanding all possible care and expenses.’ His interest in the subject was also enlightened, as he provided detailed descriptions of the traditions and ceremonies around tea and an illustrated plate giving facts about various sorts of tea.

John Coakley Lettsom (1744-1815) was also notable, here with his family in the garden of Grove Hill, Camberwell, circa 1786. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images, No. ICV No 18305. Wikimedia Commons. By an unknown English artist).

John Coakley Lettsom (1744-1815) was also notable, here with his family in the garden of Grove Hill, Camberwell, circa 1786. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images, No. ICV No 18305. Wikimedia Commons. By an unknown English artist).John Coakley Lettsom was a physician, abolitionist, Quaker and founder of the Medical Society in London in 1773. Still, he also had many connections to the Linnaean network – including Carl Linnaeus, John Fothergill (1712-1780), Daniel Solander (1733-1782), John Ellis (1710-1776), Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), et al. – due to his interest in collecting and preserving natural objects. A branch of interest, which also came to be part of this garden portrait, visible via exotic cactus species in pots and a glassed greenhouse. A contemporary small book, The Naturalist’s and Traveller’s Companion – Instructions for Collecting & Preserving Objects of Natural History, published by Lettsom in 1774, interestingly also referred to John Ellis’ work within this subject. Just like his contemporaries, Lettsom foremost gave advice about keeping seeds preserved during long sea voyages in the best way possible. One of his recommendations was: ‘The small seeds well dried may be mixed with dry sand, put into the cerate [waxed] paper or cotton, and packed in glass bottles, which are to be well corked and covered with a bladder or leather. These bottles may be put into a keg, box, or any other vessel, filled with four parts of common salt, two of saltpetre, and one part of sal armoniac, in order to keep the seeds cool, and preserve their vegetative power.’

The plant collector and physician John Fothergill also sent a letter to Linnaeus, at an unknown date, of a printed illustrated instruction named ‘Directions for taking up Plants and Shrubs, and Conveying Them by Sea’. This one page of advice also recommended that boxes should be stretched with wires on the top covered by flips of sailcloth so that dogs and cats were unable to reach the plants, but still leave the plants open for the fresh air, not mould so easily onboard a ship. ‘For each Box so hooped and netted, provide a Canvas Cover, which may when put on entirely protect it; and to prevent the Cover from being lost or mislaid, nail it to one side, and fix Loops or Hooks to the other, by which it may occasionally be fastened down.’

The ongoing correspondence between the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) and Carl Linnaeus et al. over several years in the mid-1740s also included wishes and ideas regarding what to look out for during Kalm’s forthcoming North American journey. His own particular wishes to Kalm were also part of a letter dated 17 December 1745, when he asked his former student to form appropriate plans for the following points and send them back to him:

- To collect many seeds of grass that can endure our climate.

- To acquire many species of trees that are economically useful for our manufactures and medicine and thrive in our climate.

- How our most important garden plants originate from Canada and endure year by year without special protection.

- How mulberry trees, sassafras, Radix Ninsi, etc. grow there; only one of these would pay the expedition one hundred times, not to mention the rich value to the Acts of the Academy over many years.

Interestingly, this was followed up by Kalm, who drew up a lengthy description – a type of personal instruction – which he had plans to keep up with, which he also managed to do in great detail, evident via his travel journal. This demonstrates that such writings were not always one-sided from the master’s or a professor’s point of view either, as the traveller himself could be highly involved in the process of forming what sort of plants to focus on during a lengthy trip. Beneficial endemic species seem to have been obligatory to observe wherever a naturalist travelled. Additionally, Kalm presented his handwritten document orally at a meeting held at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on 4 July 1747. That is to say, about three months before his journey commenced. Among many natural history specimens to observe and learn as much as possible about, he listed (here in an abridged version):

- Eight different types of oaks

- Mulberry trees, suitable for silkworms

- Vines and vine-leaves

- Chestnut trees and walnut trees

- Hemp, growing wild, whereof the inhabitants manufacture clothes

- A grain named fol Avoine

- An infinite number of herbs growing in meagre soils

- A number of medicinal plants

- Cedar trees and cypresses; sassafras

- Considerable numbers of roots, which they used for baking and nutrition

- Maple trees, of which a juice flows in the spring, which the Canadians boil for sugar

- A sort of bog myrtle

- Several sorts of dye grasses

Instruction for the Linnaeus apostle Peter Forsskål to be used on Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia) is not known to have been preserved, but related information was revealed by himself in at least two contemporary letters to Carl Linnaeus. Initially, on 1 January 1761, just a week before the journey commenced, he made enlightening notes about his obligations as a naturalist during the Royal expedition, equally as his loyalty to Linnaeus seems to have been steadfast.

‘My travel conditions are fairly restricted. Finally, I promised to get one [sample] of each duplicate I collect. Without that promise, I had never travelled. But take special note that everything collected according to the instruction will, after the strictest responsibility, be sent to the upper marshal of the court, Count Moltke here (who is respectful to me). Likewise, no letters which include any observations on the journey, that is to say also to Mr Archiator [Linnaeus], can be sent without being controlled and sealed by him [Moltke] first, to be sure that all glory of new discoveries stays in Denmark…’

According to the same letter, Frederik V, the King himself, clearly declared that he wanted to have a say about the scientific material either for his own interest, to be given as learned gifts or for other uses within the country. Forsskål seems to have had some reservations regarding the solid Danish patriotic aims but had even so been promised that the Swedish Queen Lovisa Ulrika and Linnaeus should be favoured with future natural history specimens. Somewhat more than a year later, in Alexandria on 2 April 1762, another of Forsskål’s letters to Linnaeus included thoughts about the Danish instruction. He noted his discovery of more than 120 plants in the desert areas close to Cairo, many of which were new to him. Due to his promise, however – as one of the members of the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia – he had to be loyal and avoid any suspicion of favouring Linnaeus. He continued in the following words: ‘I will not breach my instruction and write anything more about these matters, but in an open letter to Denmark, I will send Mr Archiator [Linnaeus] a description of two new genera…’ Overall, instructions, correspondence, journal notes, and other manuscripts to do with the preparations give essential links to why the travellers highlighted certain events, objects or specimens. In contrast, others were mentioned only in passing.

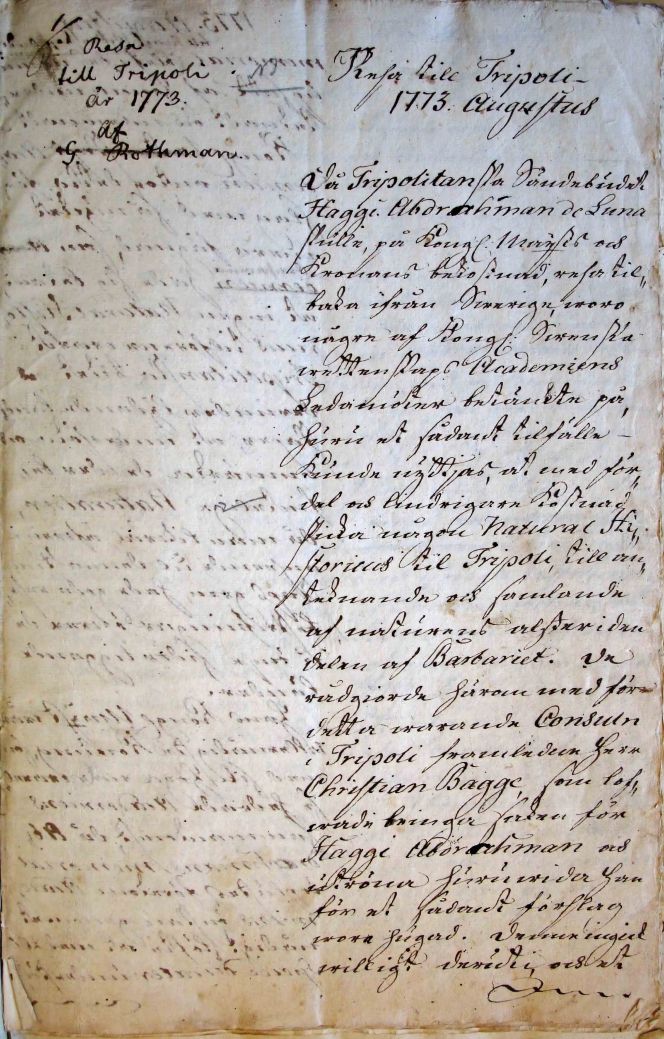

The first page of Göran Rothman’s travel journal. (Courtesy: Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien…Rothman’s travel journal 1773-1776).

The first page of Göran Rothman’s travel journal. (Courtesy: Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien…Rothman’s travel journal 1773-1776).Göran Rothman’s almost three year-long-journey started from Stockholm, when Linnaeus’ apostle, to his best abilities, tried to follow the Instructions – set out prior to his journey in June 1773 – along the route, in Tunisia and during the main stay in Libya. Judging by his journal and correspondence, the obstacles primarily came to be insufficient financial means, worries about being attacked by local groups of inhabitants on excursions, the scorching heat, and it was more challenging than expected to find a rich selection of plants. His Instruction was a seven-page manuscript from the botanist and medical doctor Peter Jonas Bergius (1730-1790) to the naturalist Göran Rothman. After his return from Tripoli in 1776, Rothman lived on for only just over two more years. This untimely death was not regarded as due to any possible after-effects of his travels but is stated as gangrene in the register of deaths and burials. It may be noted that Carl Linnaeus was an older man with declining health in 1773, which explains why the younger Bergius – who at this time was an active fellow in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences – drew up the special instructions before Rothman’s journey.

A final observation on Instructions, presented here, has been traced to one of the participants on the Imperial Academy of Sciences’ natural history expeditions in Russia from 1768 to 1774, Johan Peter Falck, who already since September 1763 had been situated in St. Petersburg as a keeper at a cabinet of natural history. During these years, he frequently complained about poor health and seems to have laid out plans for his daily life, judging by preserved correspondence to Carl Linnaeus. Despite his unhappiness, attributes such as pride and duty were seen as crucial, which was mentioned in a letter written by Falck on 25 February 1765 in St Petersburg: ‘To travel back to Sweden just as empty handed as I came from there would be unbearable and to stay in Russia, which has been insufferable from the first moment, and even more to accept a position… But, my Instruction has been attended to by the Collegium and sent to me. Take one’s oath upon is only remaining. The salary will only be 500 Rubles, including free quarters, firewood, candles and a man in attendance. If the now could give me good health, I would nevertheless be satisfied.’

Sources:

- Centrum för Vetenskapshistoria (Centre for History of Science), Sweden. (Carl Linnaeus’ three-page list of instructions prior to Pehr Löfling’s journey to Spain in 1751 & Peter Jonas Bergius ‘Instruction för Doct. Rothman på Dess tillägnade Tripolitanska resa’, 7 pages).

- Edberg, Ragnar, ‘Collecting and Preparing’, The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, Vol. One. pp. 309- 366, Hansen, L. ed, London & Whitby 2010.

- Ellis, John, Directions for Bringing over Seeds and Plants, from the East Indies and Other Distant Countries…, London 1770 (pp. 11-12).

- Falck, Johan Peter, ‘13 brev 1763-1766 till Linné från Johan Peter Falck.’ Bref och skrifvelser af och till Carl von Linné I-X 1907-1943, 1912 (p. 47. Letter from Falck to Linnaeus, St Petersburg 25 February 1765).

- Forsskål, Peter, ‘28 brev 1753-1763 till Linné från Peter Forsskål’Bref och skrifvelser af och till Carl von Linné I-X 1907-1943, (VI pp. 110-169) 1912. (Letters from Peter Forsskål to Carl Linnaeus – 1 Jan. 1761 & 2 April 1762).

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012 (Vol. One pp. 201-211 (Instructio Peregrinatoris, in an English translation & 244-247 & Vol. Two-Seven: The Linnaeus Apostles’ journals).

- Hansen, Viveka. Ed., (introduction, biography and transcription), ’Göran Rothman – Resa till Tripoli’, Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 2012, pp. 7-84.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Kungliga Biblioteket (National Library of Sweden). Manuscript: ’Tärnströms Instruktioner inför resan 1745’…

- Lettsom, John Coakley, The Naturalist’s and Traveller’s Companion – Instructions for collecting & preserving objects of Natural History, London 1774 (pp. 21-27).

- Skottsberg, Carl, Pehr Kalm – Levnadsteckning, Stockholm 1951 (pp. 100-103: Information about the instruction, 4 July 1747).

- Stockholms stadsarkiv…1779, rotel 1, no. 222 (Estate inventory of Göran Rothman).

- The Linnean Society of London: Linnean Collections, undated letter: L0000 (including printed instruction in English) from John Fothergill to Carl Linnaeus.

- Tärnström, Christopher, Christopher Tärnströms journal – En resa mellan Europa och Sydostasien år 1746,. Ed. Kristina Söderpalm, London & Whitby 2005 (pp. 222-25: the original Swedish instructions in full text).

- Uppsala University Library, Sweden (Alvin-record: 182251. Olof Rudbeck’s instruction, written in Swedish, probably shortly before the journey in 1695: Four pages, of initially six & Alvin-record: 223616, Letter 17 Dec 1745, from Carl Linnaeus, Uppsala to Pehr Kalm, Stockholm].

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE