ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

THE WEAVERS AND THEIR FAMILIES

– changing circumstances from 1750 to 1860

A complex interaction of long-lived traditions in combination with economic, social and geographical circumstances gave rise to the rich variety of woven and embroidered textiles from farmer’s homes in southernmost Sweden (Skåne) during the period 1750 to 1860. The aim of this historical essay is to demonstrate the changes in the villages and people's daily lives during the early 19th century with the assistance of artworks and maps and give details of which possible effects it had on a decorative weaving technique as double interlocked tapestries.

Market day in Lund, depicting farmers and their wives dressed in best clothes. Oil on canvas by J.W. Wallander 1858 (Cederblom, G., Svenska folklivsbilder, fig 91, 1923).

Market day in Lund, depicting farmers and their wives dressed in best clothes. Oil on canvas by J.W. Wallander 1858 (Cederblom, G., Svenska folklivsbilder, fig 91, 1923).A substantial increase in the population during the period 1750-1860 was one important reason for the farmers’ growing wealth. It was primarily the increasing life expectancy which formed the basis for the steadily growing population. Other favouring factors were more prolonged periods of peace, fewer severe epidemics, the potatoes as an essential source of nutrition and the rearrangements of the villages by law in reforms of partitioning.

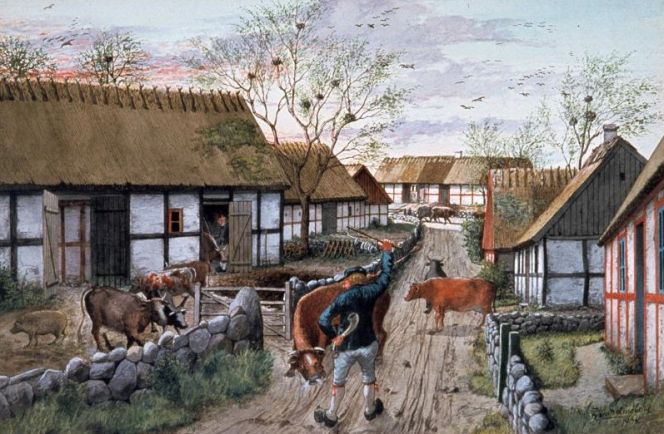

Unpartitioned village in south-eastern Skåne in early 19th-century. Water-colour by F. Lindberg 1934. (Owner: Kulturen in Lund, Sweden. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Unpartitioned village in south-eastern Skåne in early 19th-century. Water-colour by F. Lindberg 1934. (Owner: Kulturen in Lund, Sweden. Photo: The IK Foundation, London). The map depicts how the farming land was divided between the villagers of Borrie, Herrestad in south-eastern Skåne 1802, before the partitioning of the village, with all fields separated into narrow stripes. (Owner: Christinehof Archive’s map collection. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

The map depicts how the farming land was divided between the villagers of Borrie, Herrestad in south-eastern Skåne 1802, before the partitioning of the village, with all fields separated into narrow stripes. (Owner: Christinehof Archive’s map collection. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).A weaving technique such as “rölakan”, or double interlocked tapestry, was one of many traditions which developed and flourished with the more and more prosperous farmers, especially in the county of southern Skåne. This had several reasons. It can briefly be noted that the freeholders had few possibilities to increase in number when there was no more land to buy – an alternative was that ownership of land could be shared – it was instead the people without prospects of owning a property that grew. This “lower class” of country people, including crofters, dependent tenants and other poor became cheap labour for the wealthy farmers as well as for the county’s many estates. Circumstances, amongst others, contributed to the farmers’ wives improving possibilities to get more time to produce decorative textiles, which displayed the prosperity of the family, when the everyday household tasks, to a more considerable extent, could be managed by paid servants.

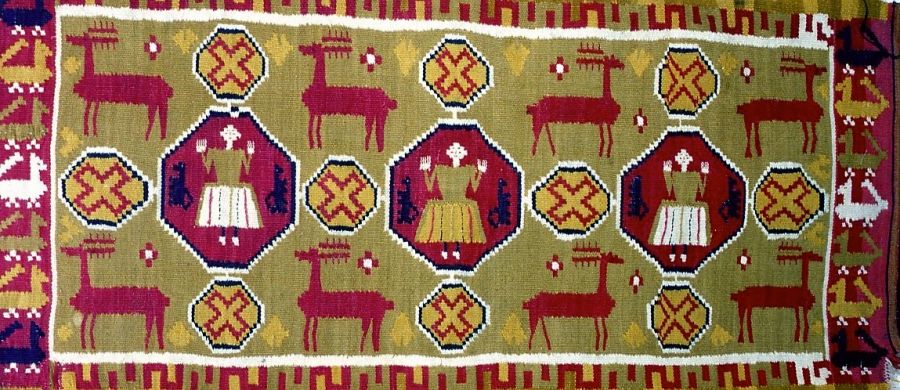

Example of cushion in double interlocked tapestry woven in the area of Herrestad, Skåne. (Owner: Malmö museums. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Example of cushion in double interlocked tapestry woven in the area of Herrestad, Skåne. (Owner: Malmö museums. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).It can not be stated with certainty which exact implications the reforms of partitioning had for the development of such textiles. However, decorative weaving and embroidering were both extensive handicrafts already before the reform, but in many areas, it increased further and became refined in the patterns during the 1820s-1840s. This can, of course, have been part of the technique as well as the development of the patterns themselves, but the improving economic advantages as the reform gave rise to also had an influence. Another reality as a result of the reform was the purely social changes, with a more isolated life on the farms outside the villages where one, to a greater extent, had to keep company/work together with the people on the farm. Most probably, this could, among other matters, make more time available for weaving when a farmer family’s number of decorative textiles more and more came to display the home’s status and wealth, at the same time as the daughters’ dowries could expand in richness and proportion.

Building work and spring farming in East Wemmenhög in southern Skåne after the reform of partitioning. Many farms now became situated outside the villages in connection with the farming land, which gave each farmer fewer but larger pieces of land to work and therefore more efficient and economical. Oil on canvas by Carl Conrad Dahlberg 1866. (Owner: Malmö museums. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

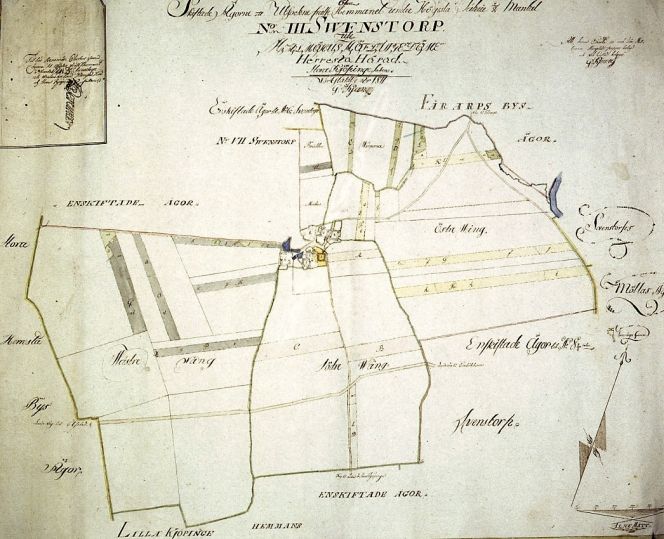

Building work and spring farming in East Wemmenhög in southern Skåne after the reform of partitioning. Many farms now became situated outside the villages in connection with the farming land, which gave each farmer fewer but larger pieces of land to work and therefore more efficient and economical. Oil on canvas by Carl Conrad Dahlberg 1866. (Owner: Malmö museums. Photo: The IK Foundation, London). The map is illustrating a selected area of Svenstorp in Herrestad 1811, after the reform of partitioning. One can clearly observe a change from the 1802 map – in the same jurisdictional district – where on the contrary the farming land only consisted of narrow stripes. (Owner: Christinehof Archive, Map collection. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

The map is illustrating a selected area of Svenstorp in Herrestad 1811, after the reform of partitioning. One can clearly observe a change from the 1802 map – in the same jurisdictional district – where on the contrary the farming land only consisted of narrow stripes. (Owner: Christinehof Archive, Map collection. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets Konst och Kulturhistoria, Christinehof 1992 (pp. 133-39).

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art, London 1996.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE