ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

WATERFALLS, FASHION & WORKING DRESS

– An Artistic Interest of Nature: 1740s to 1820s

This picture essay will look more closely at carefully constructed scenes with dramatic waterfalls as a backdrop to centred figures wearing elegant clothing due to their leisure activities as well-to-do tourists. Noticeable are the visual effects of fashionable summer clothes changing in style over the decades, together with the contrast to people in working dress, who were clearly occupied in laundry, farming, fishing or timber construction. Such artworks in natural settings – give impressions of curiosity, amazement, hard labour and even tranquillity at times intertwined with scientific advancement and observations by naturalists. A selection of waterfall scenes in Northern Europe stretching in time from the Enlightenment and up to the 1820s will be represented, with reflections further back in time to Chinese traditions. Depictions of forceful water scenes like these, however, continued to be popular motifs throughout the 19th century and were even more favoured when amateur photography was introduced in the 1890s with small easily operated hand-held cameras.

Oil on canvas by the Danish artist Erik Paulsen (1749-1790), who made a series of landscape paintings during his stay in Norway 1788-89. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, Denmark. No: KM8911. On display in 2019). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Oil on canvas by the Danish artist Erik Paulsen (1749-1790), who made a series of landscape paintings during his stay in Norway 1788-89. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, Denmark. No: KM8911. On display in 2019). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Among these landscape paintings, he painted Sarpefossen [Sarp Falls] in Norway in 1789 – with one of the most powerful and spectacular waterfalls in the country. Interestingly the picture includes visible tourists as well as working men. Notable too is that the centred portrayed lady wore a gauzy muslin dress with a broad sash, in an almost transparent cotton quality. Such a practical fashion for summer daywear was often named ‘chemise dresses’, which had become more and more popular in the 1780s due to its simplicity and new style, compared to the previous decades’ elaborate gowns. A wide-brimmed hat, maybe a straw hat, completed her fashionable outfit. The two accompanying men appear to be wearing matching broadcloth coats, waistcoats and breeches, round black hats and boots. Whilst the men, who worked with the wooden construction, wore garments made of sturdier qualities consisting of a linen shirt, a short woollen coat, breeches, stockings, a cap/hat and black shoes.

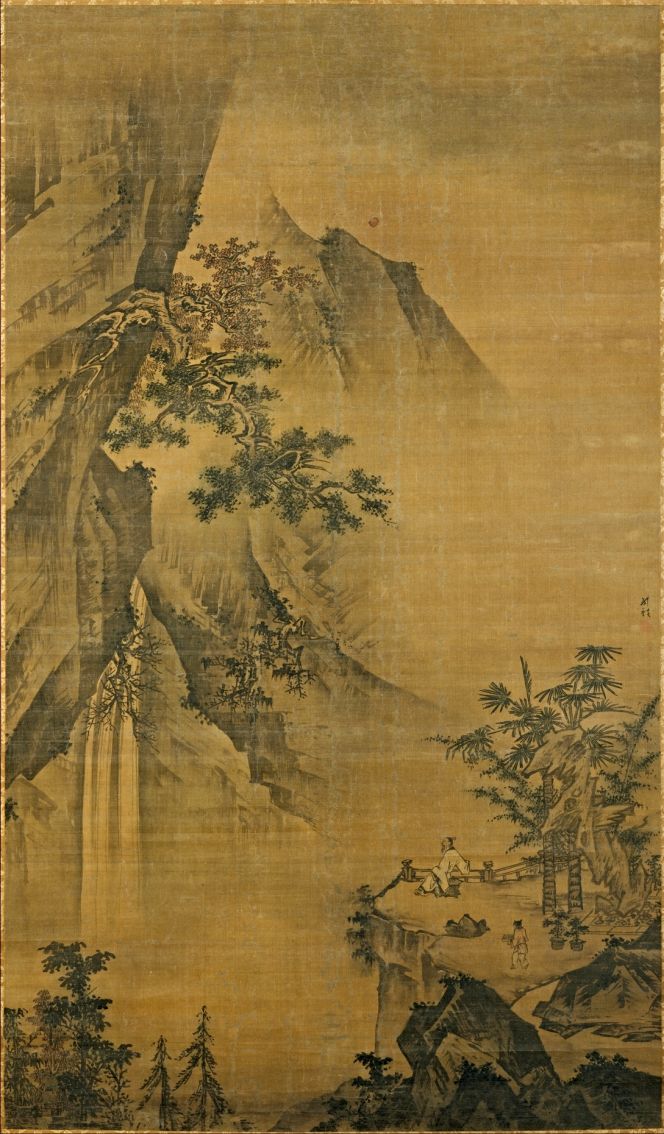

Artwork by Zhong Li, active circa 1480–1500. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Family Collection, Gift 1991. No: 1991.438.4. Public Domain).

Artwork by Zhong Li, active circa 1480–1500. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Family Collection, Gift 1991. No: 1991.438.4. Public Domain). To picture various peoples’ interest in waterfalls had a long tradition before the 18th century, particularly evident via some well-preserved Chinese paintings from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). A scene most strikingly depicted in this Ming-style picture of ‘Li Bai gazing at the waterfall on Mount Lu’ in the late 15th century – that is to say, a painting which dates 250 to 320 years prior to the chosen European artworks for this essay. The beautiful work of art gives an impression of human humbleness and fascination when putting a closeup of Nature. The informative wording by the museum collection strengthens this reality from a wealthy individual’s perspective dressed in a white or pale yellow gauzy robe: ‘There is also something quite imperial in the pose of the seated figure on the garden terrace, leaning back like the master of his universe to observe the potent forces of nature as they conduct a special performance for him alone.’

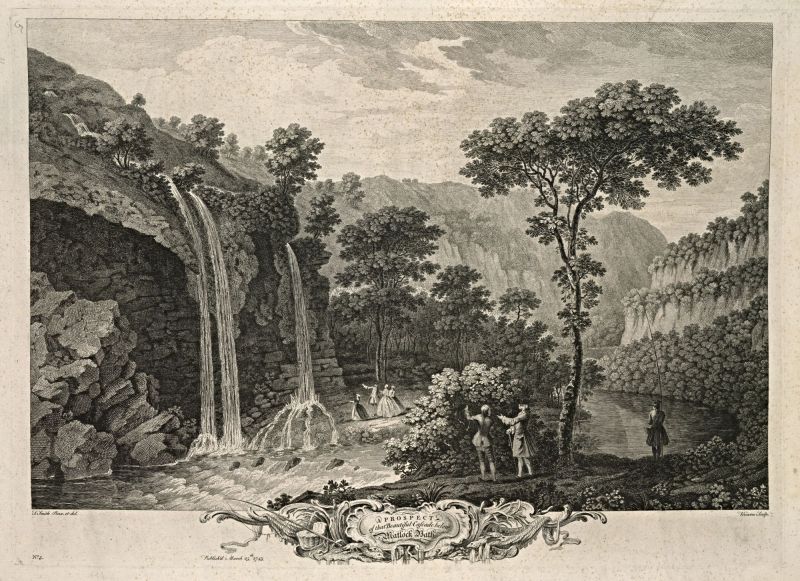

On 8th June 1748, the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) noted in his travel journal: ‘Almost all English women, both married and unmarried, used stays, lacing themselves up tightly, so that they looked very slim, especially as long as they were young and unmarried…’ This observation is an interesting comparison to how the ladies are dressed in this engraving above of, ‘The Mountainous Parts of Derbyshire and Staffordshire; commonly call’d the Peak, and the Moorlands’, just a few years earlier, in 1743. Matlock Bath in the mountainous part of the Peak was popular among early well-to-do tourists, who were curious about the breathtaking scenery with high inland cliffs, dense vegetation and waterfalls. Illustrated here, the girl wears a sack-back jacket with a contrasting petticoat, whilst the two ladies’ fashionable gowns seem to be in the shape of open-fronted bodices with elbow-length sleeves and caps or straw hats. The three wealthy men wore tricorne hats, coats with deep cuffs, long waistcoats, breeches, white stockings and black shoes. Besides the romantic natural setting, two scenes are particularly noticeable in the picture. Firstly, the man who had escorted the ladies close to the waterfall, where he appears to “explain” the spectacular fall for the amazed young ladies. Secondly, the front scene, when probably a gardener – dressed in a short jacket and baggy woollen trousers – gets instructions on which seedlings/cuttings of rare plants to bring back to the formal manor house garden.

The waterfalls at Trollhättan and Älvkarleby in Sweden. (Courtesy: Länsmuseet Gävleborg, XLM.15372. DigitaltMuseum).

The waterfalls at Trollhättan and Älvkarleby in Sweden. (Courtesy: Länsmuseet Gävleborg, XLM.15372. DigitaltMuseum).The two magnificent waterfalls at Trollhättan and Älvkarleby in Sweden were popular attractions and important waterways for fishing and transport. From a visitor's perspective, the German traveller Carl Gottlob Kuettner (1755-1805) wrote about Älvkarleby in his diary, during travels in the years 1797-99: ‘... there are scenes to paint here that are of more worth than a thousand in the most visited countries.’ Comparable to this contemporary oil on canvas by the Swedish artist Elias Martin (1739-1818) – ‘The Cascades at Älvkarleby’, painted circa 1793-98. The falls had already at this time a long history of salmon fishing, which all the illustrated men probably took part in, assisted by small rowing boats, fishing roads and nets. They were all wearing sturdy woollen short jackets, breeches, boots and hats/caps. The Romantic illustration depicts a summer's day, judging by the deciduous trees and that some men wore waistcoats and linen shirts only. In correlation, the somewhat earlier naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who just lived about 80 kilometres from Älvkarleby, instead had scientific aims to learn more about waterfalls among other physical elements. This matter was noted in his Instructions, printed in 1759 – what to carefully observe during scientific journeys abroad:’ The shores, harbours, ebb and tide of the sea, navigable or non-navigable rivers, significant waterfalls, remarkable springs (health-promoting, saline, hot), lakes and their nature and peculiarities (§8). Some of his travelling apostles also came to include notes about waterfalls in their travel journal; Pehr Kalm (already discussed in the picture above) according to fishing in Norway and frequent notes from North America with an illustration of the Cohoes fall, in the river Mohawk, before it falls into the river Hudson, together with various records in this context by Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) in southernmost Africa and Carl Peter Thunberg in his Japanese vocabulary.

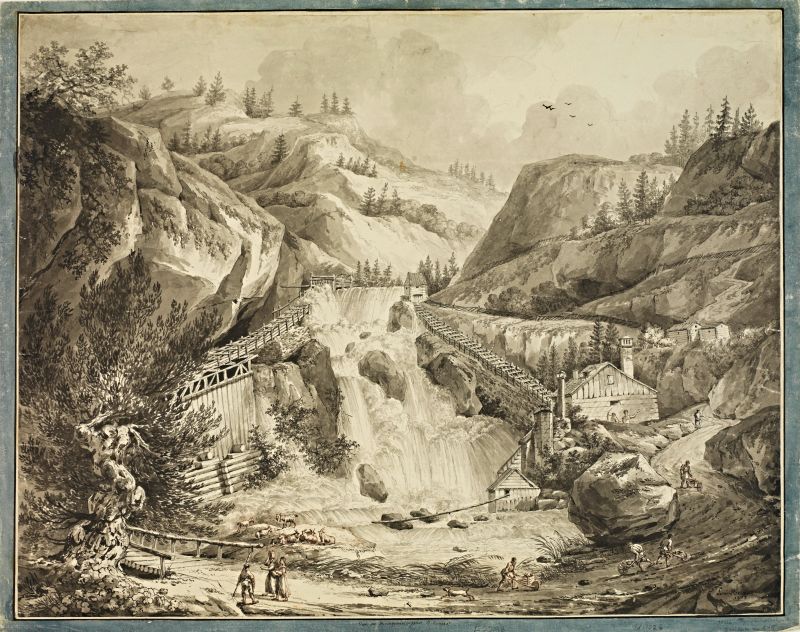

The falls at Huskvarna in Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 82039. Public Domain).

The falls at Huskvarna in Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 82039. Public Domain).The illustrated falls at Huskvarna in 1802, by the French artist Louis Belanger (1756-1816) had settled in Sweden in 1798 where he came to stay for the rest of his life and became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. Waterfall and rocks reappear in several of his artworks, of which this pen and ink drawing is an interesting example. Local men in this Swedish farming/fishing community are visibly involved in the construction or reinforcement works of the falls, which harnessed water power to cottage industries along the river. In particular, judging by the two women’s dresses, it was a summer’s day – maybe they assisted the men with food and drink. The young women wore calf-length linen shirts/chemises only, with shoulder straps – customary in many parts of southern Sweden. A linen garment, which was used under skirts, bodies and outerwear during colder periods of the year. Both women are depicted in neckerchiefs and at least one of them with a headscarf. Just like the men, they used wooden clogs during their working days. The group of men was involved in hard labour to transport stones in wheelbarrows for reinforcement of the man-made stone walls beside the falls. Their working dress consisted of wash leather breeches, a knee-length leather apron, a cap and a coarse linen shirt, equally evident via this detailed image and due to that these were traditionally hard-wearing garments commonly used by working men in many southern Swedish communities.

Oil on canvas by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783-1853). (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, Denmark. No: KM7984. On display in 2019). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Oil on canvas by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783-1853). (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, Denmark. No: KM7984. On display in 2019). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. In stark contrast to the already visualised energetic pictures, including working individuals, this almost contemporary depiction – dated 1809 – of a small waterfall portrayed visiting well-to-do individuals at a walking distance from Liselund Manor on the Island of Møn during a summer's day. This is an oil on canvas by the Danish artist Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, who is regarded to have been the most important artist for the introduction of the Golden Age of Danish Painting in the early 19th century. He and several other artists of this movement not necessarily painted powerful waterfalls but on the theme of water settings in Nature – they preferred one or several individuals strolling close to rivulets, viewing a lake or a sea view with sailing boats at a distance. Tranquillity, fashionability in dress, portraits, luxuriant trees and beauty from all sorts of perspectives in interiors and outdoor scenes alike were dominating features. The two women’s clothes worn in this particular painting include the same style of white gauzy cotton dress with classical drapes and a high waistline, contrasting coloured shawl and a green cap. Whilst the gentleman was also dressed in the latest fashion, consisting of a tall conical black hat, tightly fitted leather breeches reaching to the boots and probably a double-breasted frock coat, linen shirt with high collar and waistcoat. The arrangement of the three figures and the guidebook/map shows the company’s apparent interest in the waterfall.

Watercolour by the Swedish landscape painter Gustaf Erik Westerling (1774-1852). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 85302. Public Domain).

Watercolour by the Swedish landscape painter Gustaf Erik Westerling (1774-1852). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 85302. Public Domain).This depiction of an unidentified Swedish landscape is dated 1824. Interestingly, this final example of waterfall pictures also includes a group of laundering women and fishing men. Good access to water was vital for laundering and living close to a river with a slow, but constant motion of the water was ideal when washing and rinsing garments. However, the two young women in focus seem surprisingly fashionable. They appear to be wearing single-coloured dresses, tied up to one side when doing their laundry, of a dress model with a natural waistline and plain round collar, together with flat slippers and white stockings. The woman standing slightly behind the two may have been a servant, judging by her striped fabric apron. Whilst the three fishing men used a variety of traditional working garments. Particularly noticeable is the man in a red woollen jacket and brown breeches holding a fishing rod, who wore a wide-brimmed hat with a low crown. A hat model that had been part of up-to-date fashion already in the 17th century, but continued to be part of the traditional dress in farming /fishing communities – in some southern Swedish provinces up to the first half of the 19th century.

Sources:

- Ashelford, Jane, The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society 1500-1914, London 2002.

- Hansen, Lars, ed. The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, Volume Eight, London & Whitby 2012 (Vol. One. pp. 91 & 206 | Vol. One: Carl Linnaeus’ Instruction p. 206. & Vol. Three, Five & Six: Fashionable clothing and waterfalls observed by three of the travelling apostles).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 52-54: Observations by Pehr Kalm, ladies’ dress in 1740s England).

- Kuettner, Carl Gottlob, Reise durch...Schweden...1798. vol. 2, Leipzig 1801.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Instructio Peregrinatoris …, Uppsala 1759.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (Collection online, quote & information related to the Ming style picture, 1991.438.4).

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Folkdräkter, Nordiska museets Handlingar 77, Stockholm 1971.

- Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery Denmark), København, Denmark. | Visit the

exhibitions in 2019.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE