ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

WOOLLEN STOCKINGS

– Traditions and Trade in Whitby: 1670s-1910s

Knitted stockings were important export items in many coastal areas of England and Wales already during the seventeenth century – Whitby was no exception. Stockings from Yorkshire were usually knitted in wool qualities, to be used as a warm, water-resistant and durable article of clothing. This essay will take a closer look at such evidence via port books, census reports, adverts in local newspapers, photographs, directories and clothes lists for Arctic travels during an almost 250-year-long period. However, at the time of my research at the Whitby Museum, only two pairs of stockings had been preserved in this collection, both of cotton. Overall, it seems rare for more than a hundred-year-old woollen stocking to end up in museum collections. Stockings and socks, most of the time, were darned or patched until the toe and heel were totally worn out. On coarser worsted models, the ankle piece could even be reused by unraveling the yarn and knitting a new foot for the stocking.

One of the most informative ways to study knitted stockings from the period 1880s to 1910s is via local photographs. This picture taken by the photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in the last decade of the 19th century, depicts the fisherman Tom Langlands on Tate Hill Pier in Whitby – with his initials TL visible on the stocking. Fishermen often wore long knitted woollen stockings of this kind that reached far above the knee, on many contemporary photographs however, this garment is “hidden” under the boots due to that the upper part of the boots reached above the knees, when not folded down like on this picture. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 19-15 & detail of picture/collage. (Whitby Lit. & Phil.)

One of the most informative ways to study knitted stockings from the period 1880s to 1910s is via local photographs. This picture taken by the photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in the last decade of the 19th century, depicts the fisherman Tom Langlands on Tate Hill Pier in Whitby – with his initials TL visible on the stocking. Fishermen often wore long knitted woollen stockings of this kind that reached far above the knee, on many contemporary photographs however, this garment is “hidden” under the boots due to that the upper part of the boots reached above the knees, when not folded down like on this picture. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 19-15 & detail of picture/collage. (Whitby Lit. & Phil.)Much earlier evidence has been possible to trace via the Whitby Port Books, documents which recorded textile-related goods, above all the knitted stockings that often arrived in the harbour for export – principally to be sent to France, Flanders and Holland. Here is an example from 7 February 1674:

‘twenty dozen children’s woollen stockings

two dozen men's woollen stockings’

Another early primary source connected to stockings in Whitby is to be found in a probate inventory dated 1703. According to this, the widow Sarah Harrison left such a large quantity of mixed textiles that she – or possibly her late husband since many of the listed items are described as ‘old’ – must have run some kind of small haberdashery business. Especially with reference to ‘37 skeins of yarn, 4 pairs of stockings, 15 handkerchiefs, 20 old hoods, 30 old pinners, 4 old neckcloths, 1 small parcel of hood lining’.

Whilst references to stockings mostly originate from the 19th century, the first in the form of a rare printed advertisement dated 1813 for ‘Mrs Craigs’ Shop in Bridge-Street’. She sold all kinds of fine cloths and accessories at ‘Prime Cost’; in other words, the proprietor offered her stock for the best possible prices that would bring neither profit nor loss to herself. ‘A Large and Choice Assortment of Printed Cottons, Sarcenets, Ginghams, Shawls, and Muslins of all descriptions; Calicoes, Silk Handkerchiefs, Flannels, Worsted and Cotton Stockings, &c. &c. Whitby, Feb. 11, 1813’. The textile goods mentioned in the printed advertisement include ‘Worsted and Cotton Stockings’, implying that Mrs Craig chose not to use the word ‘hosiery’ in marketing her wares. The term ‘hosiery’ for knitted products is found as early as the 1760s in documents referring to cargoes for outward bound ships, but the word ‘hosier’ is not found in Whitby until 1818, when it occurs on the print reproduced earlier showing ‘Hebron Linen Draper Haberdasher Hosiers’ in Old Market Place.

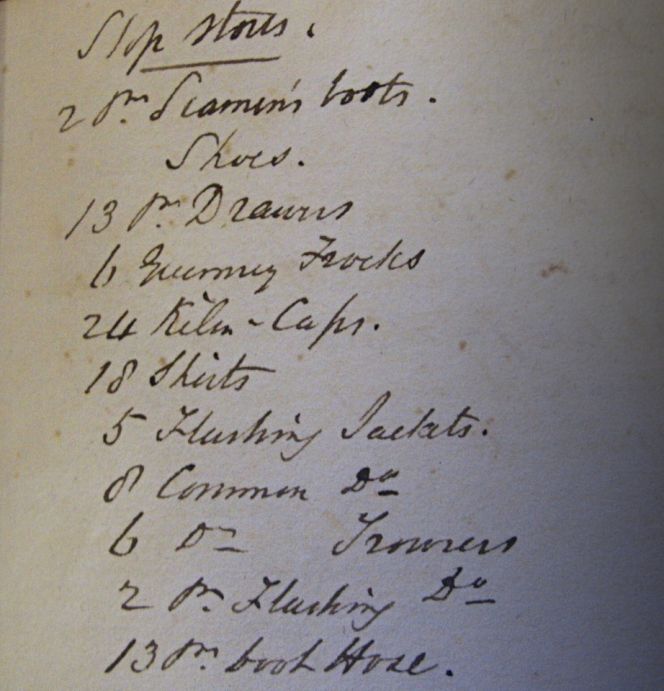

The fact that the whaler and Arctic explorer William Scoresby the Younger had seven pairs of new Iceland stockings and ten pairs of old ones, underlines the need to have a good supply of warm, dry clothes constantly available during these voyages from Whitby harbour to the Arctic in the 1810s and 1820s. In his notebook dated 1821, this note on ‘Slop stores’ was registered too, that is to say a store of clothes kept on board that could be sold to any of the sailors whose stock of clothes was short of any particular item. Apart from the Iceland stockings, it can be assumed that most of these garments were probably made by Whitby tailors, while the knitted garments also would have been produced locally in the town or the surrounding district. Notice at the end, ’13 pair boot Hose’ or warm knee-length woollen stockings. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Scoresby Collection, Scoresby Baffin Notebook 1821, SCO596.

The fact that the whaler and Arctic explorer William Scoresby the Younger had seven pairs of new Iceland stockings and ten pairs of old ones, underlines the need to have a good supply of warm, dry clothes constantly available during these voyages from Whitby harbour to the Arctic in the 1810s and 1820s. In his notebook dated 1821, this note on ‘Slop stores’ was registered too, that is to say a store of clothes kept on board that could be sold to any of the sailors whose stock of clothes was short of any particular item. Apart from the Iceland stockings, it can be assumed that most of these garments were probably made by Whitby tailors, while the knitted garments also would have been produced locally in the town or the surrounding district. Notice at the end, ’13 pair boot Hose’ or warm knee-length woollen stockings. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Scoresby Collection, Scoresby Baffin Notebook 1821, SCO596.Around the time of Scoresby’s Arctic voyages and in the coming decades, local Whitby businesses can also be linked to stockings among other textile goods. In particular registered in Baines’s (1823), Pigot’s (1834) and White’s (1840) directories, who all listed hosiers active in those years in Whitby.

Hosiers – 1823

- Hebron Thomas, Old Market place Limb Charles,

- Sandgate Storer John, Bridge street

Hosiers – 1834

- Leng William, Bridge st

- Limb Charles, Sandgate

Hosiers – 1840

- Leng Wm (tea dealer), Bridge st

- Limb Charles, Sandgate

The 1823 directory further indicates that many of the ‘linen and woollen drapers’ were also ‘hosiers’, meaning that they sold knitted garments like stockings, caps and sweaters. Hebron’s business – visualised on a Whitby print from 1818 – reappears in 1823, while Charles Limb is listed as a hosier in all three directories. Both the hosiers Leng and Limb can also be found in the 1837 Poor Law Valuation of Whitby, which reveals that both tradesmen were ‘owner’ as well as ‘occupier’ of their respective addresses with ‘Shop and dwelling-house’. It can be presumed that William Leng was the younger of the two, since he is mentioned as late as 1864 in Slater’s directory, and also in the censuses of 1841 and 1851 (aged 50 and 59), while no trace remains of the hosier Charles Limb after 1840.

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe has captured sheep being washed in a stream close to the North York Moors, circa 1890s. The wool was washed to clean it and make it easier to handle during and after shearing. Notice the man to the right, who seems to oversee the work, wearing visible woollen stockings in his low boots. There is no historical evidence of local mechanical spinning mills in Whitby from the end of the 18th century or later though, so the town’s traders must have imported the various kinds of wool yarn their customers required from elsewhere in England or from abroad (examples in advert below). If spinning by hand was practised locally around the time for this photograph, it was as small-scale handicraft. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 8-13).

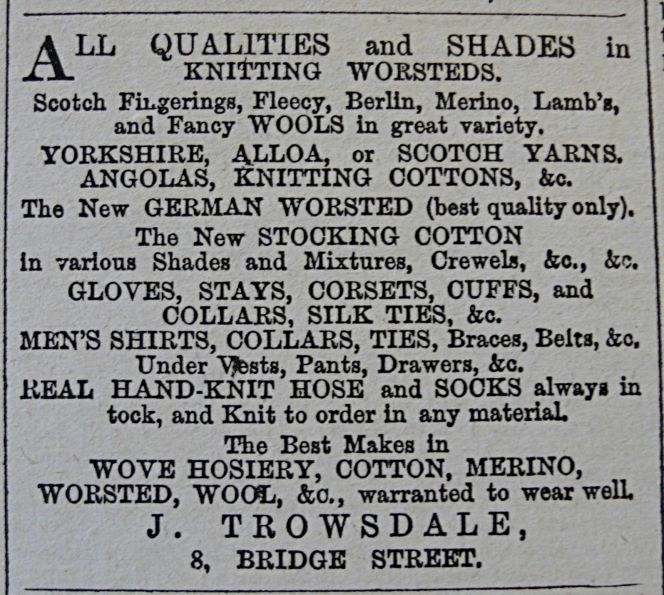

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe has captured sheep being washed in a stream close to the North York Moors, circa 1890s. The wool was washed to clean it and make it easier to handle during and after shearing. Notice the man to the right, who seems to oversee the work, wearing visible woollen stockings in his low boots. There is no historical evidence of local mechanical spinning mills in Whitby from the end of the 18th century or later though, so the town’s traders must have imported the various kinds of wool yarn their customers required from elsewhere in England or from abroad (examples in advert below). If spinning by hand was practised locally around the time for this photograph, it was as small-scale handicraft. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 8-13). During the years 1870 to 1880 J. Trowsdale frequently advertised in the Whitby Gazette with references to all kinds of yarn for knitting as well as ready-knitted stockings of various qualities from his stock in Bridge Street. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1880, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

During the years 1870 to 1880 J. Trowsdale frequently advertised in the Whitby Gazette with references to all kinds of yarn for knitting as well as ready-knitted stockings of various qualities from his stock in Bridge Street. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1880, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Few people claimed knitting as their occupation in the census reports of 1841-1911, whether by hand or machine. In 1841 the word ‘knitting’ is not even mentioned, though one man of twenty does appear as a ‘stocking weaver’, which would have involved mechanically “woven” stockings with a knitted structure. This kind of work can be traced further back in the parish church registers, in which three men are described as ‘stocking weavers’ at the baptisms of their children in the year 1800, though none appears again. The 1851 census includes the 66 year-old widow Ann Scott, who lived in Baxtergate and worked with ‘Manual Labour Knitting’, but after her no other knitter appears for twenty years, until the unmarried 61 year-old Elisabeth Jackson of Haggersgate who gave her occupation in 1871 as ‘Knitting’. Both these women may have knitted stockings or sweaters, either to sell themselves or for some shop in Whitby that sold hand-knitted garments. For instance, Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room in Flowergate advertised ‘Knitting’ in 1855 in the Whitby Gazette, and she continued to advertise until 1864. Other advertisers of the time who may have needed hand-knitters were T. Bland in 1865 for his or her ‘Best Knitted Guernseys, Worsted Stockings...’; and J. Trowsdale (illustrated above), who between 1870 and 1880 sold ‘Knitting Worsteds, Fingering Wools, Fleecy, Berlin & Lamb Wools, Angoras, Knitting Cotton &c’.

The 1881 census mentions a ‘Stocking Knitter’ called Lizetta Gibson, a 45 year-old widow living off Haggersgate. This hand-knitter does not reappear in 1891, but now 15 year-old Cathrine Bonwick of Church Street is listed as a ‘Knitting Machinist’. This girl was living with her parents George and Cathrine Bonwick, who were both 48 years old and ‘Hosier Manufacturers’. The father, G. H. Bonwick of Church Street, had already advertised in the Whitby Gazette in 1885 as a ‘Wholesale and Retail Stocking, Guernsey, and General Knitter’. It is impossible to say how long the Bonwick family were active as machine knitters in Whitby, but they are not mentioned in the censuses of either 1881 or 1901, and only advertised in the local paper in the mid-1880s. A woman of the time who accepted orders for knitting was a Mrs Bell who in 1890 offered ‘Stockings, Socks, Vests, Petticoats, &c.m, knit to order’. In other words, there was a demand for individually made garments to be knitted precisely according to the customer’s instructions. The 1901 census mentions two women as combining knitting with other work. These were both widows: 74 year-old Jane Kitching of The Cragg whose work was ‘Plain Sewing Shirt & Knitter’, and 32 year-old Ellen Hill of Church Street, a ‘Washerwoman & Knitter’ who also chose to add that she was employed. Whether her employment was as a washerwoman or as a knitter or both is unclear. But what these women knitters had in common was that they were all either widows or unmarried. In other words, needed to earn their living at one of the occupations possible for single women at the time. In the 1911 census, no woman claimed knitting as her paid work, but there can be no doubt that hand-knitting clothes for family needs must continue to be part of everyday life in Whitby after this time.

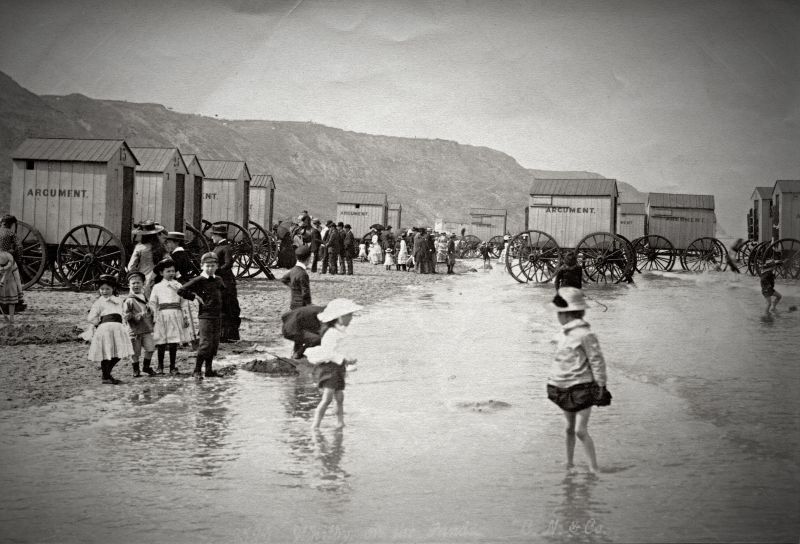

Some of the children in this 1880s picture have taken off their warm stockings to cool off in the summer warmth, possibly on a family vacation on Whitby beach. Whilst poor children in photographs taken in the town’s lanes would go barefoot all summer so as not to wear out their shoes and socks, which is evident on several of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s outdoor photographs. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, C 2524, unknown photographer).

Some of the children in this 1880s picture have taken off their warm stockings to cool off in the summer warmth, possibly on a family vacation on Whitby beach. Whilst poor children in photographs taken in the town’s lanes would go barefoot all summer so as not to wear out their shoes and socks, which is evident on several of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s outdoor photographs. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, C 2524, unknown photographer). Coarse warm socks or stockings needed darning from time to time. However, no Whitby photograph shows this craft, but in one taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in nearby village of Glaisdale, the elderly Mrs Ann Scarth is sitting in her doorway darning a long stocking. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 24-8).

Coarse warm socks or stockings needed darning from time to time. However, no Whitby photograph shows this craft, but in one taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in nearby village of Glaisdale, the elderly Mrs Ann Scarth is sitting in her doorway darning a long stocking. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 24-8).In conclusion from a wider English perspective. The hand-knitting industry in England reached its peak during the 16th and 17th centuries, providing an occupation and generating an income for a considerable number of knitters. The main centres were London, Nottingham, Leicester, Norfolk and Yorkshire, but as early as 1589 William Lee in London invented a mechanical process enabling knitting to be done faster and with more consistent results. This was the so-called stocking frame which within a hundred years made possible in many places the creation of an important cottage industry for the hosiery trade. Even so, hand-knitting survived alongside machine production for several reasons. Hand-knitting required little equipment and could be done while sitting or walking, or after dark by firelight, enabling short free moments to be used for making clothing for the family or for sale. Also, a problem with knitting clothes on stocking frames was the fact that the process had been largely standardised for many years, allowing little room for changes in fashion, design, or material, while a woman knitting by hand was freer to adopt new ideas. Hand-knitted products also had the advantage of being cheaper for the customer, since the women, children and old people who made them were paid astonishingly little.

Meanwhile, frame-work knitters were more expensive since having invested money in their mechanised equipment, they were considered to be skilled workers. In any case, coarse socks knitted by hand were often thought to be more hard-wearing, or to put it another way, one got better quality without paying more. So hand-knitting survived as a business option, even if suffering increasing competition already in the early 19th century while it also remained a convenient way of knitting clothes for one’s own family requirements – by many a popular handicraft even up to present-day.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 14, 102-115, 176-177, 234-238, 273, 277 & 281-285. | For full Bibliography and a complete List of notes, see this book).

- The National Archives at Kew. (1837 Poor Law Valuation Whitby, MH12/14656).

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1841-1901 microfilm, 1911 online source).

- Whitby Museum, Library and Archive. A large number of primary sources | Photographic Collection – Frank Meadow Sutcliffe. | Costume & Textile Collection. (Whitby Lit. & Phil). (Research visits 2007-2011, including Whitby Gazette 1855-1911, photographs and preserved stockings).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE