ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

WORKING DRESS, FASHION AND TEXTILE RAW MATERIALS

– in 18th Century Gardens

The history of gardens has often crossed my path during textile research. It may have been via etchings of wealthy visitors dressed in the latest fashion or gardeners in working dress, positioned in close surroundings of a manor house. Other evidence of purely economic or domestic use has been traced from contemporary written sources, for example, in travel journals describing dye plants and mulberry trees in experimental plantations or botanical gardens. This essay will give a few examples of such observations, including various portrayed individuals as well as the exotic garden as a prominent status symbol – and how utilitarian gardens were put to the best possible use in a perspective of textile raw materials and dyes.

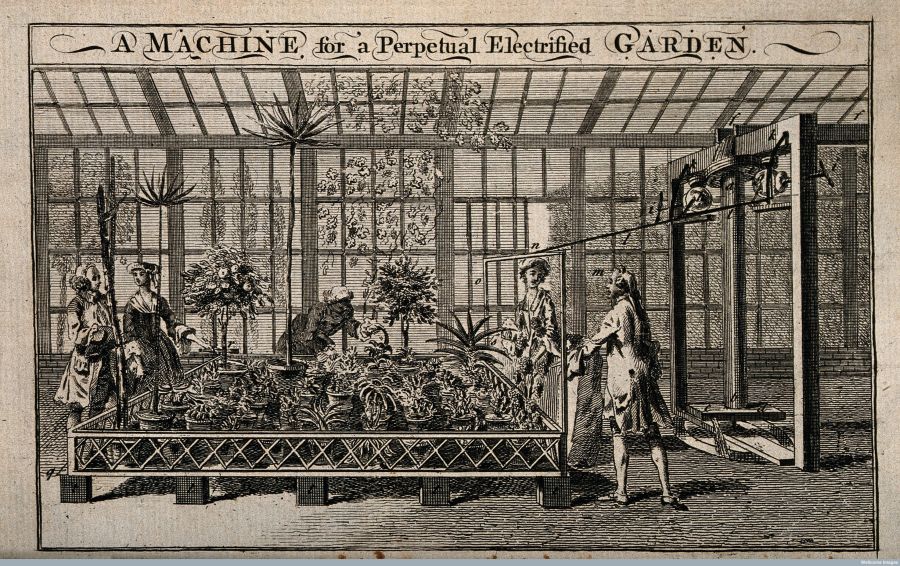

Etching from ca 1755 depicting a gardener/female servant in a somewhat concealed position, together with wealthy owners or visitors judging by the sumptuous and fashionable clothing. All four viewing ‘A Machine or a perpetual Electrified Garden’ used in a large glasshouse. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London no. V0016451).

Etching from ca 1755 depicting a gardener/female servant in a somewhat concealed position, together with wealthy owners or visitors judging by the sumptuous and fashionable clothing. All four viewing ‘A Machine or a perpetual Electrified Garden’ used in a large glasshouse. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London no. V0016451).Leisure activities, luxury statements, walking or riding wealthy individuals in extensive gardens, greenhouses and orangeries with plants from far-flung parts of the world were often present in these prints and etchings. An increasing trade via both East and West India Companies in Europe, scientific exploration, Grand Tours, curiosity of everything “exotic”, as well as imperial expansion were important factors in making it possible for the prosperous in their everyday life to enjoy mulberry trees, carnations, figs, lemons etc all year around. At different levels, this influenced the lives of royals, the landed aristocracy, the gentry, the bourgeois, merchants and farmers. “An idealised view of a gentleman’s garden” was also a popular feature on etchings, with the fashionably dressed owner of the manor house gardening side by side with the gardeners in working dress.

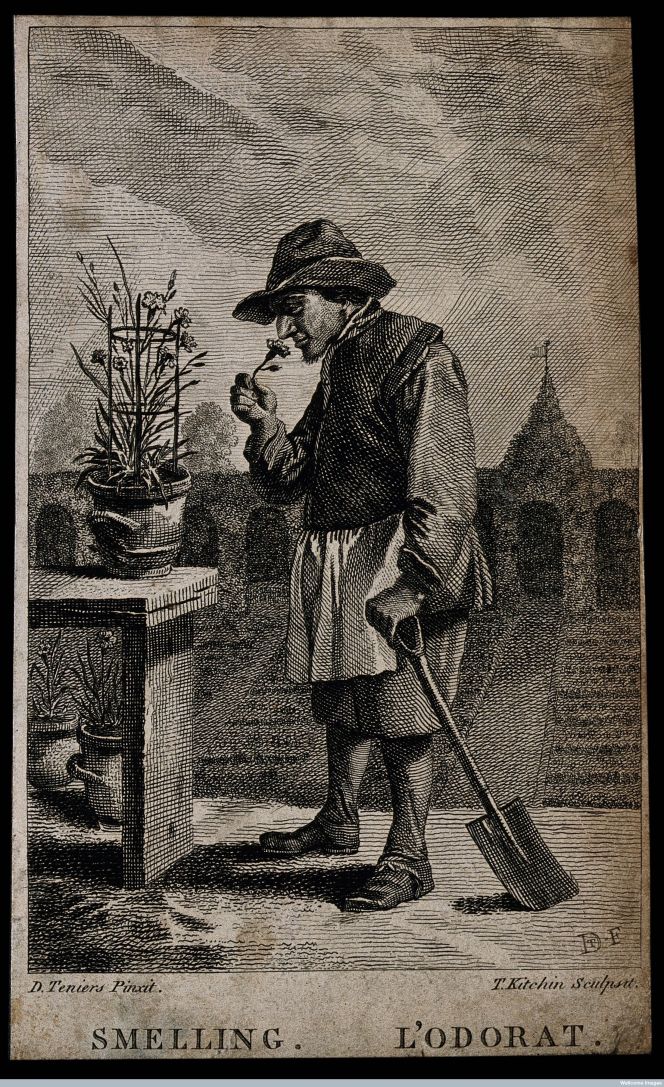

Etching of unknown date by Thomas Kitchin (1718-1784) after David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) showing ‘A gardener smelling a flower’. The image gives a clear picture of his working dress, including a practical linen smock, but also that he worked for a wealthy household due to the desirable carnations in several garden pots etc. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0007698).

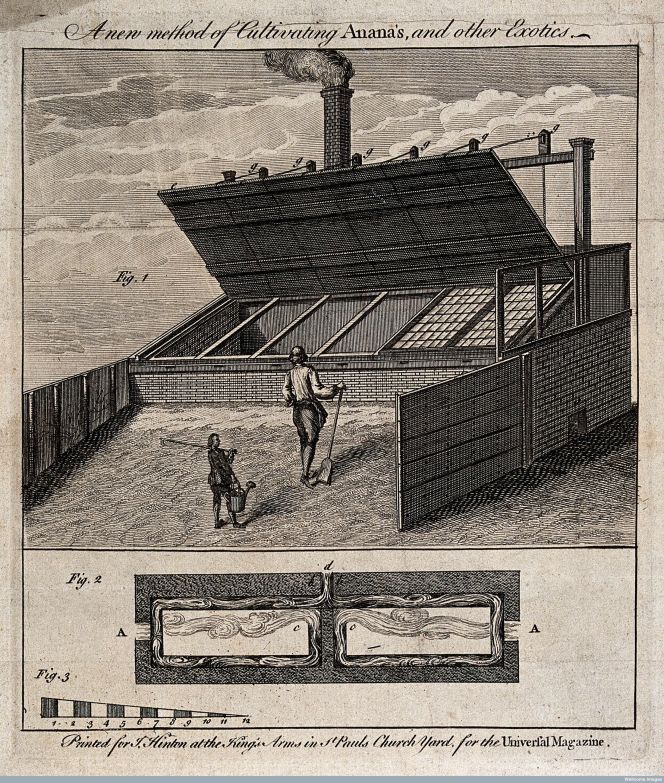

Etching of unknown date by Thomas Kitchin (1718-1784) after David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) showing ‘A gardener smelling a flower’. The image gives a clear picture of his working dress, including a practical linen smock, but also that he worked for a wealthy household due to the desirable carnations in several garden pots etc. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0007698). The main objective for this engraving dating ca 1750 is the large ‘Type of greenhouse’ for ‘Ananas, and other Exotics’ in England, but it is also possible to study some details of the gardener’s and his young assistant’s clothing. Their dress is more difficult to identify in exactness compared to the gardener’s on the previous image, but maybe a linen smock (or everyday shirt/jacket for upper garments) and breeches were used. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0025736).

The main objective for this engraving dating ca 1750 is the large ‘Type of greenhouse’ for ‘Ananas, and other Exotics’ in England, but it is also possible to study some details of the gardener’s and his young assistant’s clothing. Their dress is more difficult to identify in exactness compared to the gardener’s on the previous image, but maybe a linen smock (or everyday shirt/jacket for upper garments) and breeches were used. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. V0025736). A depiction of a third gardener is sprung from a totally different tradition where the main objection is to impress, dating ca 1721. He is portrayed with tools, a parterr sketch, listed and numbered exotic plants, the most desired flowers for a wealthy household, citrus plants and carnations in pots – furthermore his dress looks very sumptuous made of the finest silks. It may be assumed that he was the head gardener at a castle or great manor house on the Continent, as the coloured engraving was made by Martin Engelbrecht from Augsburg. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. L0037480).

A depiction of a third gardener is sprung from a totally different tradition where the main objection is to impress, dating ca 1721. He is portrayed with tools, a parterr sketch, listed and numbered exotic plants, the most desired flowers for a wealthy household, citrus plants and carnations in pots – furthermore his dress looks very sumptuous made of the finest silks. It may be assumed that he was the head gardener at a castle or great manor house on the Continent, as the coloured engraving was made by Martin Engelbrecht from Augsburg. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library, London, no. L0037480).It was not only the Dutch, English, French and present-day Germany gardens that presented a multitude of exotic plants; manor houses in the Nordic countries also featured greenhouse and orangery plants of importance. An informative example can, for instance, be found in an inventory of 1738 from the Hesselbyholm garden near Stockholm in Sweden, showing cultivation of such plants as ‘fig trees, mulberry trees, peach trees, orange trees, lemon trees, bitter (Seville) orange trees, small bay trees’. From a textile perspective, the cultivation of mulberry trees is interesting as the dream of domestic sericulture was reinforced from around the 1730s through decrees against extravagance in an attempt to limit the import of silk and velvet. Whether these trees were intended for sericulture, the sweet berries or merely a decorative feature in the garden is difficult to say for certain as they are described as ‘15 large mulberry trees in large basins’. That the trees were already large by the year 1738, and moreover placed in basins, may indicate that what was described as the black mulberry tree, Morus nigra, on which the silkworms do not thrive as well as on Morus alba.

Life-size picture-board dummies were popular to place in manor gardens already in late 17th century and continued to be so during the coming century. This lady may be assumed to depict a servant of a wealthy household in the 1790s, but depictions of elegant guests, gardeners and individuals from “exotic” countries are also represented on preserved dummies of this type. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0097091A-B. Digitalt Museum).

Life-size picture-board dummies were popular to place in manor gardens already in late 17th century and continued to be so during the coming century. This lady may be assumed to depict a servant of a wealthy household in the 1790s, but depictions of elegant guests, gardeners and individuals from “exotic” countries are also represented on preserved dummies of this type. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0097091A-B. Digitalt Museum). No life-size picture board dummies were mentioned in the Hesselbyholm inventory from 1738, but other decorative features were included, and maybe some of them depicted individuals. For example, on page 4 of the inventory, in the Winter Quarter ’38 Images thereof, 4 large which have 4 pedestals and 16 smaller with fine pedestals’ were listed. Additional adornment in the same quarter included ’45 painted flower canes with gilded tops’. Despite such detailed notes of expensive decorative plants and accessories, in this garden, as well as in most gardens, the useful and economic realities were just as important as in the previous century. Including all areas of horticulture – medicinal plants, vegetable and fruit plantations, herbs, as well as possible raw materials such as flax and dye plants. Natural dyes and the economic advantages of domestic plantations for south-after dyestuffs were also studied by Carl Linnaeus and his seventeen “Apostles” in the period 1730s to 1790s.

![Plain woven linen or woollen cloths were practical when keeping, handling or transporting heavy or delicate garden vegetables and fruits – on this oil on canvas such a cloth was depicted with “a giant pumpkin”. The written note included in the artwork by Olof Fridsberg (1728-1795), reads in translation from the Swedish: ‘Grown in the garden of Åkerö in year 1757, and weighed 115 skålpund [pounds/ca 50 kilos]’. Furthermore Fridsberg was not only a visiting artist in this garden, as he worked for count Carl Gustaf Tessin at Åkerö manor house in Sweden during a fifteen year period from 1756 to 1770. (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 700. Wikimedia Commons).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/6-garden-1750s-800x695.jpg) Plain woven linen or woollen cloths were practical when keeping, handling or transporting heavy or delicate garden vegetables and fruits – on this oil on canvas such a cloth was depicted with “a giant pumpkin”. The written note included in the artwork by Olof Fridsberg (1728-1795), reads in translation from the Swedish: ‘Grown in the garden of Åkerö in year 1757, and weighed 115 skålpund [pounds/ca 50 kilos]’. Furthermore Fridsberg was not only a visiting artist in this garden, as he worked for count Carl Gustaf Tessin at Åkerö manor house in Sweden during a fifteen year period from 1756 to 1770. (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 700. Wikimedia Commons).

Plain woven linen or woollen cloths were practical when keeping, handling or transporting heavy or delicate garden vegetables and fruits – on this oil on canvas such a cloth was depicted with “a giant pumpkin”. The written note included in the artwork by Olof Fridsberg (1728-1795), reads in translation from the Swedish: ‘Grown in the garden of Åkerö in year 1757, and weighed 115 skålpund [pounds/ca 50 kilos]’. Furthermore Fridsberg was not only a visiting artist in this garden, as he worked for count Carl Gustaf Tessin at Åkerö manor house in Sweden during a fifteen year period from 1756 to 1770. (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 700. Wikimedia Commons). Notice: All quotes from the 18th century Hesselbyholm manuscript, in translation from Swedish.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, The Piper Family Archive (Christinehofs slottsarkiv, Piperska arkivet), Sweden. ‘Inventory of the garden of Hesselbyholm 1738’, (D/IIa).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Hesselbyholms trädgård år 1738 – En återblick på barockträdgårdens blomstrande prakt’, Lustgården 1990-1991, pp. 71-88.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Quest-Ritson, Charles, The English Garden – A Social History, London 2001.

- Wellcome Library (Information on catalogue cards).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE